- ‘Sorted’ for Es? Women and Ecstasy in 1990s Britain - October 28, 2020

Growing up in Britain in the mid ‘90s, the name, and image, of Leah Betts featured prominently in my drugs education. Black billboards across the UK proclaimed: “Sorted – just one ecstasy tablet took Leah Betts.” A Polaroid picture of Betts on a life-support machine, shortly before she died after taking an Ecstasy pill at her eighteenth birthday party, was circulated widely around secondary (high) schools. The message that I understandably took from this material was that, in the words of South Park, a programme popular with adolescent boys around the time, “drugs are bad, m’kay?”

But I also became aware that if ecstasy and other drugs were bad, they were particularly bad for young women. Male pop stars such as East 17’s Brian Harvey notoriously boasted in 1997 that he took twelve Ecstasy pills in one night with no serious consequences, while Noel Gallagher of Oasis – at that point Britain’s biggest band – described taking drugs as “like getting up and having a cup of tea in the morning.” For men therefore, Ecstasy was an everyday, laddish indulgence, whilst for women, it was a fatal vice. These half-remembered impressions of my teenage years have subsequently been reinforced by my academic research.

Author Marek Kohn (1996), writing in History Workshop at the time, drew a comparison between one of the subjects of his book Dope Girls – Freda Kempton,who died from a cocaine overdose in 1922 – and the salutary case of Betts:

“Both women were young; both died as a consequence of taking illegal drugs; both became posthumous examples whose fate was suggested to express a fundamental truth about the nature of illicit drug use. Both took a stimulant drug associated with a popular dance subculture of questionable legitimacy.”

– Marek Kohn

The “fundamental truth” that Kohn pointed out was the moral opprobrium that routinely greets female use of psychoactive substances, while the “popular dance subculture of questionable legitimacy” was, in Ecstasy’s case, “rave.”

Raves, Women, and Ecstasy

Ecstasy, or 3,4-Methylene-dioxy-meth-amphetamine (MDMA), was patented by Merck in 1914, before disappearing into obscurity until its reinvention by Californian chemist Alexander Shulgin in the 1960s. It was subsequently used experimentally in psychotherapeutic contexts such as relationship counselling for couples. But Ecstasy’s cultural moment came when it became used recreationally, initially in nightclubs in Dallas, Texas. By the mid-1980s, Ecstasy reached the UK, and its psychoactive properties, including euphoria, hallucinogenic effects and increased energy, were a perfect foil for the new house and techno music sweeping through British nightlife. What had started as an exclusive designer drug at fashionable nightclubs was soon being consumed at massive illegal “raves” with thousands of attendees, and by 1992 an estimated half a million young people were taking the drug regularly.

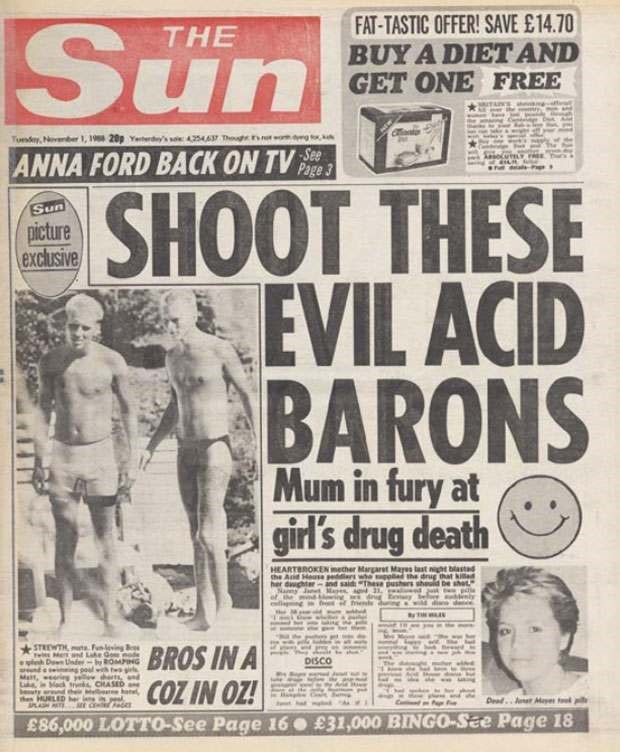

Alongside such widespread use, there were also a handful of unfortunate fatalities, which the British tabloid press were keen to publicise. The first widely-reported ecstasy-related deaths were of young women; Janet Mayes, following a party in Hampton Court, south west London in the autumn of 1988, and Claire Leighton, after an evening spent at fabled Manchester nightclub The Haçienda in July 1989. Doctors warned of users engaged in a “dance of death,” while harm reduction charities produced materials advising users on safer consumption.

Lifeline and Harm Reduction

One such organisation was Lifeline, an organisation active in Manchester since 1971, who had developed a character called Peanut Pete, based on a real-life raver who had engaged with their services, who had “a big nose, a head shaped vaguely like a peanut and his baseball cap on the wrong way around.”

Pete’s exploits ran over the course of several comics distributed to ravers outside clubs and in record shops and hairdressers, but Lifeline suspected that both his appearance and laddish exploits were not cutting through to the significant numbers of female ravers. As sociologist Angela McRobbie (1994) has written, while “[g]irls appear, for example, to be less involved in the cultural production of rave, from the flyers, to the events, to the DJing,” the emphasis on dancing, “where girls were always found in subcultures … gives girls a new-found confidence and a prominence.”

Described by Lifeline researcher Kellie Sherlock (1994) as “female version[s] of Peanut Pete,” Claire and Jose were subsequently developed by Lifeline, in consultation with focus groups. Their adventures across three comics illustrated some of the tensions with gender at the heart of rave culture, but also the ways in which Lifeline were responding to this apparently new drug.

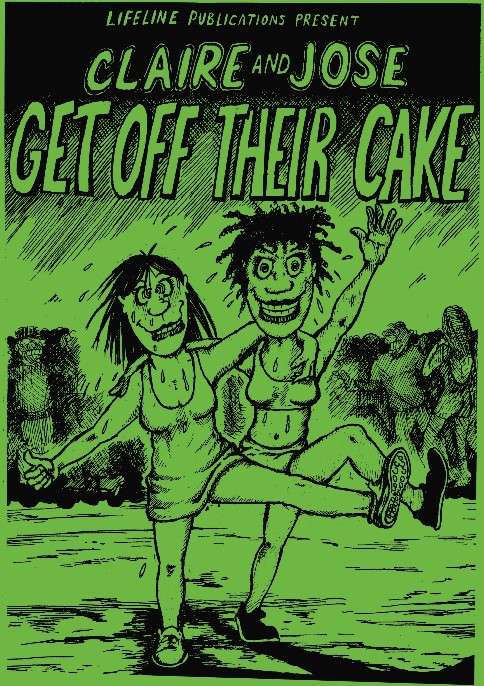

Claire and Jose Get Off Their Cake

The first comic, Claire and Jose Get Off their Cake, confronted how women might navigate the apparently masculine world of raves. Driving to a rave with their male friends, Claire was eager to demonstrate that her tolerance for recreational substances matched their peers. As a pre-rave marijuana joint was passed round, Claire bragged that “I can smoke the bollocks [British slang for testicles] off you any day matey,” whilst when the Ecstasy pills were distributed with a suggestion that the women might want to moderate their consumption, Claire responded that she would “neck [take] what you do.”

Inevitably, Claire ran into problems, as she realises she is “losing control” and “on a mad one.” Asking herself “why didn’t I take a half like Jose did?,” Claire’s difficulties are compounded by her time of the month. Part of Claire’s motivation to “get right off my tits” was the desire to forget all about her “tammy” (tampon). Lifeline’s explanatory notes on the back of the pamphlet made the moral of the story explicit; women shouldn’t try to match men, pill for pill. Noting that where once taking drugs and raving were thought of as “boys only,” Lifeline warned that “a man and a woman can take the same amount of the same drug and feel totally different…because women’s bodies are generally smaller than men’s, making the effects of drugs feel much stronger.”

As for Claire’s unusual method for coping with her period, this was taken as a prompt to inform women that not only was such consumption inadvisable as a pain relief mechanism, but also that overindulgence could even make periods “heavier or irregular…They may even stop.” Lifeline therefore leaned on biological differences between sexes, characterizing women as both smaller physically and beholden to their menstrual cycles, in order to question their use of psychoactive substances.

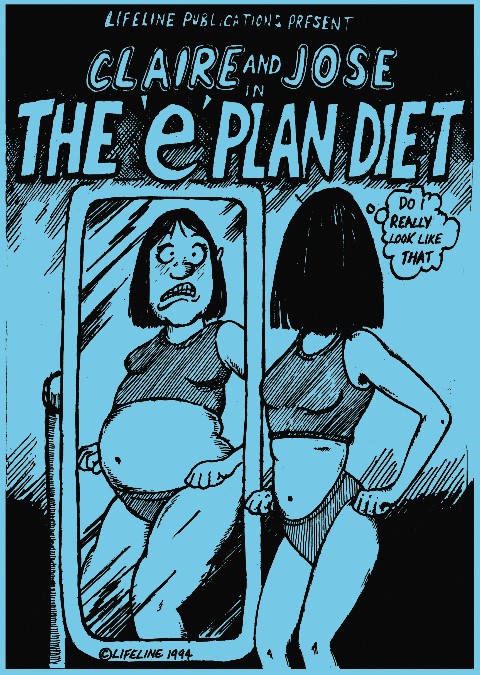

A further two comics featured Claire and Jose, and addressed perceived feminine issues such as body dysmorphia (The E-Plan Diet) and sexually predatory men (Mr Wonderful). Across these three publications, Lifeline presented an environment that they characterized elsewhere as “Club Dangerous,” reminding readers that Ecstasy could provide only temporary respite for both the social and biological travails of being a young woman.

Female Pleasure

But in presenting this image, Lifeline ran counter to both research conducted under their auspices, and a wider conversation about ecstasy and female pleasure. Sociologists such as Maria Pini (2001), Fiona Hutton (2006) and Sharron Hinchliff (2001) suggest that for many women, the appeal of raves and clubs was in fact the freedom that these settings afforded. The apparent effects of Ecstasy – a weightless bliss, empathy, and an intense affinity with the repetitive and rapturous music pounding from the speakers – facilitated an environment of communality quite different from earlier eras of clubbing.

Combined with the androgynous apparel worn by ravers such as baggy t-shirts and dungarees, and the physiological effects documented amongst men in terms of sexual function or rather lack of, raves seemingly afforded a safer space for women. Indeed, Sheila Henderson (1993) had conducted extensive research for Lifeline with women from 1991 onwards, and concluded that “the scene has provided a social space for young women to pursue these pleasures without uninvited sexual attention.”

Join us at Sacred Plants in the Americas II

Conclusion

What might we learn from these contrasting depictions of women’s experiences of Ecstasy in 1990s Britain? In Dope Girls, Marek Kohn (1992) suggested that hysteria around female drug use and its understanding as a “crisis of young womanhood” was “a remarkable cultural spasm, [a] discourse that has remained immune to the passage of three-quarters of a century.” In Lifeline’s material, like their interwar antecedents, women were represented as highly vulnerable to the dangers of a wider subculture. Their agency and pleasure was obscured by rhetorics of harm, risk and ultimately, death.

In Lifeline’s material, like their interwar antecedents, women were represented as highly vulnerable to the dangers of a wider subculture. Their agency and pleasure was obscured by rhetorics of harm, risk, and ultimately, death.

A further quarter of century on, and maybe attitudes have shifted a little. Millennial essayist du jour Jia Tolentino (2019) recently linked her use of MDMA – via the Canadian poet Anne Carson – to the ecstatic, even mystical, experiences of a diverse cast of female voices such as French philosopher Simone Weil, English medieval anchorite Julian of Norwich, and the Archaic Greek poet Sappho. Tolentino’s reclamation of Ecstasy therefore asks us to reconsider lived experiences of this psychoactive substance, but also to be attendant to longer histories of women and female pleasure.

Art by Marialba Quesada.

Take a minute to browse our stock:

Did you enjoy reading this article?

Please support Chacruna's work by donating to us. We are an independent organization and we offer free education and advocacy for psychedelic plant medicines. We are a team of dedicated volunteers!

Can you help Chacruna advance cultural understanding around these substances?