I want to know my body

I want this out not in me

I want no other leakage

I want to know no secrets yet

I’ll leave

Oh I’ll leave

No I’ll leave care

Free of distortions

Free of distortions

Free of distortions

Clinic: Distortions (2000)

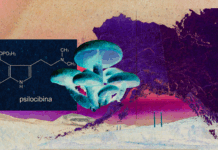

2019 will go down in the History of Psychedelia as a major tipping point in the collective effort to turn Western societies again into legal zones for the use of psychedelic plants and fungi. The year marks the success of the first two citywide decriminalization initiatives for naturally- occurring psychedelics in the United States: psilocybin mushrooms in Denver, Colorado; and psychedelic plants and fungi in Oakland, California (Santa Cruz followed Oakland at the beginning of 2020). This means that the cultivation, possession, and consumption of these plants and fungi by adults has officially become the lowest law-enforcement priority. Similar efforts are incubating in dozens of cities across the US, and two statewide ballot initiatives in Oregon are currently campaigning for a model that would make psilocybin legally available under (non-medical) supervision in specific centers, and overall drug decriminalization, respectively.

These initiatives signal the power of grassroots movements to generate sociopolitical change in a space that has been dominated by the medicalization agenda of psychedelic scientists and advocates for the last two decades. Many psychedelic researchers and therapists are in favor of decriminalization. Others, however, including prominent scientists and the food-journalist-turned-psychedelics-spokesperson, Michael Pollan, are more cautious or even skeptical. While all positions have their place in the psychedelic ecosystem, my task as a social scientist studying this field is not just to map but also to critically examine them. In my project on the medicalization of psychedelics in the United States, I have started to investigate how scientists and other stakeholders advocating for and supporting psychedelic science position themselves towards decriminalization efforts. In this article, I tackle the arguments of decriminalization skeptics and present a politically informed and evidence-based recommendation for why psychedelic researchers should not push back against decriminalization.

Listening to Michael Pollan’s Echo Among Psychedelic Researchers

After the psilocybin mushroom campaign won in Denver in May 2019, Michael Pollan1 2 urged decriminalization activists to slow down because the public and policy-makers were not ready to make evidence-based decisions. He claimed that science needed more time to finish its work. From his perspective, science should come first and decriminalization maybe second, sometime in the future (for a more detailed critique of Pollan’s position see Labate et al. 2019).3 This delaying approach is echoed among some of the psychedelic researchers I interviewed. They also share Pollan’s concern that decriminalization could potentially contribute to accidents and a change in the current positive cultural climate towards psychedelics. In the worst case, this is envisioned to lead to a moral panic and a repressive government response against the science—just like in the 1960s. As one of my interviewees stated: “I’m in agreement with several, I would say, most researchers, and even Michael Pollan, that these initiatives in the United States right now might create an unfortunate backlash politically if there are adverse events out there in the public.” Similarly, another experienced psychedelic researcher worries that decriminalization could “create the potential that more people are going to experiment on their own, more people who do not know much about these compounds and do not understand how to optimize set and setting and optimize safety parameters. More people are likely to get into trouble and then the media will bounce all over this.”

So, ironically, these researchers and Michael Pollan are trying to obstruct a process they have started themselves.

Let’s scrutinize these expectations. First, we do not know yet whether more people will be drawn to use psychedelics after decriminalization. My research indicates that many people have started experimenting with psychedelics after reading about the promising psychedelic studies in the media and in Michael Pollan’s How to Change Your Mind (2018). So, ironically, these researchers and Michael Pollan are trying to obstruct a process they have started themselves. Second, nobody in the field of psychedelic science and the decriminalization movement questions the importance of publicly accessible and scientifically-based information on how to create a safe set and setting, dosages, and drug testing. All of this is relevant regardless of decriminalization. As the soap manufacturer, philanthropist, and activist, David Bronner4 recently pointed out, the existing prohibitionist framework is actively preventing the spreading of such information that could help to avert harmful outcomes. In effect, then, changing this framework through decriminalization and other drug policy reform approaches would be the most effective risk reduction measure. Third, it is by far from settled what role adverse events, the media, and other actors such as scientists themselves played in enabling the backlash in the Sixties. In addition, we don’t know whether a similar dynamic could repeat itself under present circumstances.

Why There is no Apolitical Stance on Psychedelics

“Keeping the politics out” is a rhetorical move we should always be skeptical of, particularly so in the realm of psychedelics.

One big underlying issue that is dividing the psychedelic science field in its assessment of decriminalization is the relationship between science and politics, which entails the question of whether and how psychedelic researchers should position themselves towards drug policy reform. Among the spectrum of opinions, we can identify two main opposing camps: on the one side, those who take a public stand on drug policy reform and, on the other side, those who wanted to “keep the politics out.” “Keeping the politics out” is a rhetorical move we should always be skeptical of, particularly so in the realm of psychedelics. This move tries to turn a blind eye to the reality that the criminalization of psychedelics and other drugs in the 1960s, leading up to the draconian Controlled Substances Act, wasn’t driven by scientific evidence but rather by President Nixon’s self-preserving politics. As evidenced in a statement of former Nixon advisor John Ehrlichman,5 the drug scheduling system and the overall stigmatization of specific substances was part of Nixon’s attempt to subdue political opponents and racial communities who were known to use drugs such as marijuana. When Michael Pollan6 urges his readers not to “politicize” psilocybin at this point in time, he asks them to ignore that psychedelics have already been politicized by being criminalized in the first place. This very fact makes them a matter of public and political concern, and there is therefore no way of approaching them from an apolitical stance.

When Michael Pollan urges his readers not to “politicize” psilocybin at this point in time, he asks them to ignore that psychedelics have already been politicized by being criminalized in the first place.

Curing “Psychedelic Researcher Anxiety Syndrome”

The fact that some psychedelic researchers suffer from a culturally-induced affliction we could label “Psychedelic Researcher Anxiety Syndrome” shows that they are entangled with drug policy.

What moves Michael Pollan and other psychedelic researchers to distance themselves from drug policy movements is an emotion: fear. One of my interviewees felt compelled to diagnose a prominent psychedelic researcher: “He’s like a worried mother. He just feels like the way you show your love is by anxiety. You worry about everything. And he is impervious to data. … It’s like a personality setting, this anxiety.” Rather than psychologizing the issue, I want to propose a sociopolitical explanation. The case demonstrates that the collective trauma of prohibition continues its ripple effects, even in the minds of the most esteemed psychedelic researchers. The fact that some psychedelic researchers suffer from a culturally-induced affliction we could label “Psychedelic Researcher Anxiety Syndrome” shows that they are entangled with drug policy. The Syndrome is nothing other than their attempt to cope with the fundamental uncertainty about what could trigger a similar “illogical” political backlash as was seen in the late 1960s. The irrational scheduling system causes some of the scientists to act irrationally themselves and project their fears onto the next potentially controversial issue that could be used to disguise a self-serving political decision as “rational” response. Overcoming the trauma of prohibition takes the conscious, concerted effort of many actors. In the studies the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS) is conducting, volunteers are receiving MDMA to work through their trauma and heal their PTSD. Rewriting traumatic memories into a new, coherent story seems to be at the core of the healing mechanism. Moving through fear and making meaning of experiences that seemed incomprehensible at first are central elements in this process.

If there exists a cure for “Psychedelic Researcher Anxiety Syndrome,” it lies in moving right through the fear and into a thorough investigation of the underlying political narrative that was created by President Nixon to undergird the War on Drugs.

Could MDMA-assisted psychotherapy, then, maybe, also help psychedelic researchers? I think that, when it comes to “Psychedelic Researcher Anxiety Syndrome,” MDMA will not be the answer. It isn’t even the answer in MDMA-assisted psychotherapy for the treatment of PTSD, where the MDMA is just catalyzing the rewriting process and the hard work still needs to be done by the patient-therapists team. But questioning the status quo, looking deeper into what was and is, can help us as a society to arrive at a new understanding, out of which an alternative story can be woven. If there exists a cure for “Psychedelic Researcher Anxiety Syndrome,” it lies in moving right through the fear and into a thorough investigation of the underlying political narrative that was created by President Nixon to undergird the War on Drugs. Psychedelic researchers and other actors in the psychedelic space must be careful to avoid buying into the fear-based realities of elected officials, and anticipate opposition that might not even exist or might simply be unfounded. The solution also cannot lie in the impulse that tries to cut science off from politics. In its original Greek sense, “politics” does not just mean “governance” but also “for, or relating to citizens.” In such a broader conception, psychedelic researchers are called upon to embrace their role as political actors rather than dissociate from it. This also means doing their work and framing its implications with the benefit of all citizens in mind, not just those patients who happen to be diagnosed according to specific criteria. From such a vantage point, pushing back against decriminalization just doesn’t make sense.

Valuing Value-Based Science-Policy Decisions

For this very reason, we need a multidisciplinary approach in the governance of psychedelics that combines medical and natural scientific knowledge with expertise from the social sciences, history, religious studies, and philosophy.

A nuanced approach towards the reintegration of psychedelics into society recognizes that each path—be it medicalization, decriminalization, or legalization—has its merit. Instead of weighing paths against each other, we should try to responsibly shape each one of them. Scientific results and other forms of knowledge have their place in this process, but data needs to be interpreted. The ways these interpretations come about are always, and necessarily have to be, value-based decisions that consider specific individual consequences as well as societal ones. Therefore, what is needed is value-based, science-informed decision-making that takes a broad variety of factors into account, ranging from biological, psychological, philosophical, social, and spiritual to economic ones. For this very reason, we need a multidisciplinary approach in the governance of psychedelics that combines medical and natural scientific knowledge with expertise from the social sciences, history, religious studies, and philosophy.

My social scientific perspective encourages psychedelic researchers to embrace their political responsibility and critically engage with the effects of irrational laws and their associated official narratives on themselves and the rest of society. Psychedelic scientists are not above, but shaped by, the skewed prohibitionist reality people in most Western nation states currently live in. At the same time, science has the power to reshape regulations and broader society in ways that can make the world more livable and equitable. It is this reality-altering power that needs to be leveraged to correct the still lingering one-sided, self-serving, and therefore unjust, policies from the past. Adopting such an approach will not only help to cure “Psychedelic Researcher Anxiety Syndrome” but also contribute to the creation of a post-prohibitionist world in which human beings can flourish, thanks to the healing potential of psychedelic plants and fungi.

Art by Mariom Luna.

—

Note:

Thanks to Denia Djokić and Rachael Petersen for their helpful comments on an earlier version of this article. This article represents an output of a project funded by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie action grant agreement No 788945.

References

- Pollan, M. (2019a, May 10). Not so fast on psychedelic mushrooms. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/05/10/opinion/denver-mushrooms-psilocybin.html ↩

- Pollan, M. (2019b, June 12). Where I stand on magic mushrooms. GEN Medium. https://gen.medium.com/where-michael-pollan-stands-on-magic-mushrooms-6a17053a55fd ↩

- Labate, B. C., McAllister, S., & Ribeirio, S. (2019, May 13). It’s time to enthusiastically celebrate Denver’s historic victory to decriminalize psilocybin mushrooms. Chacruna.net. https://chacruna.net/its-time-to-enthusiastically-celebrate-denvers-historic-victory-to-decriminalize-psilocybin-mushrooms/ ↩

- Bronner, D. (2020). The unified field theory of psychedelic integration and Portugal style decriminalization. MAPS Bulletin, 30(1), 14–19. ↩

- Baum, D. (2016, April). Legalize it all. How to win the War on Drugs. Harper’s Magazine, pp. 22-32. ↩

- Pollan, M. (2019b, June 12). Where I stand on magic mushrooms. GEN Medium. https://gen.medium.com/where-michael-pollan-stands-on-magic-mushrooms-6a17053a55fd ↩

Take a minute to browse our stock:

Did you enjoy reading this article?

Please support Chacruna's work by donating to us. We are an independent organization and we offer free education and advocacy for psychedelic plant medicines. We are a team of dedicated volunteers!

Can you help Chacruna advance cultural understanding around these substances?