“The question about women’s role in the history of plant-psychedelic use in society is a fascinating topic.”

Marlene Dobkin de Rios

Thus remarked Marlene Dobkin de Rios (née Dobkin) in her autobiography, a vivid account that traced her decades of experience as a medical anthropologist and transcultural psychotherapist. Over the course of her career, Dobkin de Rios explored a range of topics: fortune telling cards and the Rorschach; witchcraft and psychosomatic illness; visual arts, music, and drug use. Most of her work, however, focused on the healing practices and therapeutics of Peruvian curanderos—local healthcare practitioners—that often braided together a range of techniques.

Ayahuasca’s place in mestizo and Indigenous Peruvian healing practices featured extensively in Dobkin de Rios’ work, and the world of popular psychedelics has often referred to her as the “mother of ayahuasca.” Her story in the history of hallucinogenic plants is indeed a fascinating and complex one. It demonstrates why we need to go beyond “recovering” women in the history of psychedelics to instead explore the often tense and tender relationships that characterized such psychedelic research, especially in Latin America.

Enter, Anthropology

Marlene Dobkin was born in New York in 1939. Upon finishing high school at the age of fifteen, she embarked on her post-secondary studies at Queen’s College at the City University of New York, where she majored in psychology. After college, she began graduate school at New York University, with the intention to pursue a career in social work. However, she was drawn to anthropology and graduated with an MA in the discipline in 1963. She obtained a teaching position at the University of Massachusetts and considered various topics for her PhD research. A serendipitous meeting in Montréal ushered the young scholar into the world of hallucinogenic research.

While visiting friends in Montréal, she met Oscar Ríos (no relation), a Peruvian psychiatrist working at McGill University’s Transcultural Psychiatry Division. Ríos had grown up in Iquitos, an Amazonian city in northeastern Peru that had long captured the imagination of intrepid travelers and is today revered by many as the “ayahuasca capital.” In 1962, Ríos completed his medical degree at San Marcos University in Lima and set out to expand his research on the psychiatric potentials of psychoactive chemicals and plants. His colleagues insisted that he include an anthropologist on his research team. With the Peruvian psychiatrist requiring the expertise of an anthropologist and the U.S. anthropologist still seeking a dissertation, the two began a fruitful, transnational collaboration.

Join us at Sacred Plants in the Americas II

Peruvian Research and Relations

Following her meeting with Ríos, in 1967, Dobkin began an enduring relationship with the Institute of Social Psychiatry in Lima. Under the guidance of the Peruvian psychiatrist Carlos Alberto Seguín, she conducted a study on the ritual healing of the “mescaline cactus” in the northwestern region of Salas, the “capital of witchcraft.” Following this project, Dobkin returned to Lima and conducted ethnographic work with Ríos in his northeastern hometown of Iquitos. They examined patients that travelled to ayahuasca healing ceremonies to observe which types of therapeutics local healers used. She remarked that nearly everyone she spoke with in Iquitos had taken ayahuasca at least once for health reasons. While Dobkin and Ríos eventually drifted apart in their research activities and interests, her time in Iquitos shaped much of her future research.

Early on in her research, Dobkin became fascinated with naipes—fortune-telling cards that were popular amongst both curanderos in Iquitos and those in metropolitan Lima’s middle class. In Iquitos, Dobkin began to read the fortunes of her informants. After encouragement from Ari Kiev, a renowned psychiatrist she had met while in New York in 1968, Dobkin began requesting modest compensation for reading fortunes. She described herself as a “full-fledged curiosa, a specialist who could divine the future.” As a demand for her services grew, she opened a consultation office, where two of her friends in Iquitos would send her new clients, who “practically lined up to have their fortunes read.” Dobkin embraced her new label in the city as the “gringa [female outsider] who knew things.”

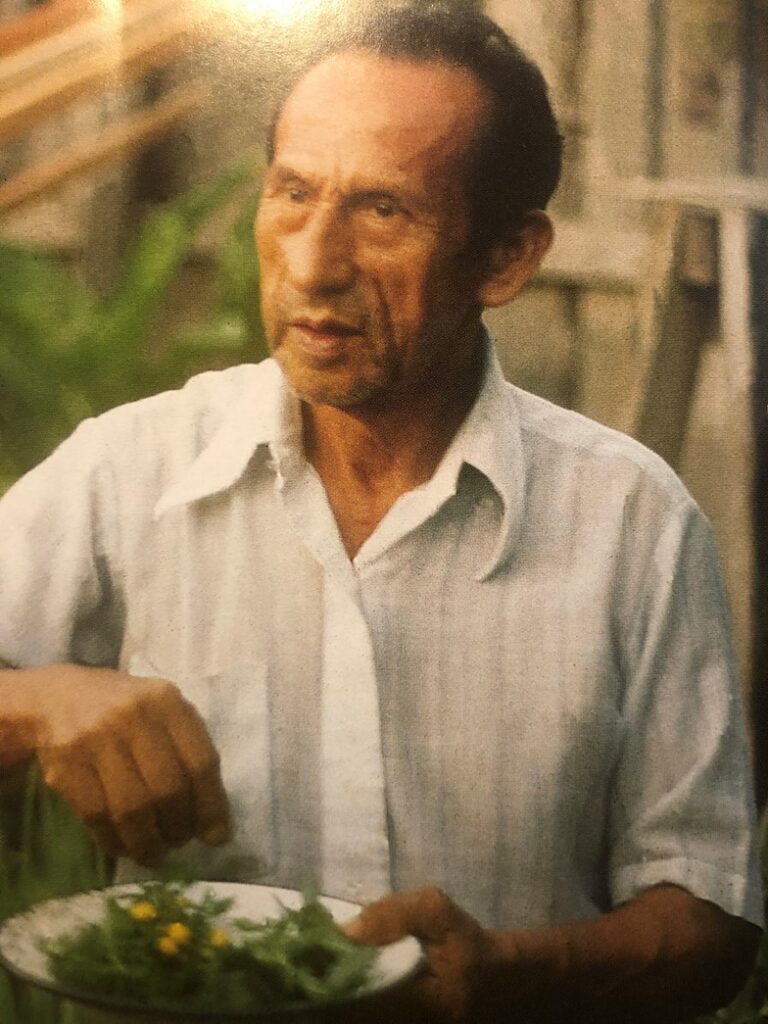

While she was conducting her fieldwork Dobkin met her husband, Yando Hildebrando de Rios, an artist who would contribute several illustrations for her work over the years. Her husband had grown up witnessing and experiencing ayahuasca healing practices as his father, don Hildebrando de Rios, was a local healer and vidente, or seer, in Pucallpa in eastern Peru. For her research in Peru, newly married Dobkin de Rios received her PhD in anthropology from the University of California Riverside and began teaching at California State University at Fullerton. In the late 1970s, she returned to Peru with her husband and daughter to conduct a formal ethnographic study of her father-in-law and his patients.

Dobkin de Rios described don Hilde, as he was known by his patients, as a “master herbalist and drug healer who uses the psychoactive plant, ayahuasca.” He, too, read naipes with his clients. The anthropologist observed that don Hilde would see as many as 25 patients a day, most of whom were women, and over half young children. Dobkin de Rios remarked that the patients came with a range of ailments, ranging from bodily complaints to concerns about bewitchment. Often, his patients would see biomedical physicians for their ailments as well.

As with many folk practitioners who included ayahuasca in their therapeutic repertoire, don Hilde communicated with entities and spirits “that come to him in his visions to instruct him about healing plants.” Dobkin de Rios recounted his practices, which relied on ayahuasca and toé (or white angel’s trumpet [brugmansia suaveolens]), another hallucinogenic plant: “He began to mix toé with ayahuasca to have special kinds of visions, first taking the ayahuasca then the toé, and looking carefully at each patient assembled in the main room [of his clinic] to see to the very depths of their intestines… When it is a natural illness, don Hilde feels different impressions of his own body, and experiences the person’s pain subjectively. In this way he is able to identify where the patient’s illness is located.”

Dobkin de Rios, as the daughter-in-law of don Hilde, occupied a special position in the clinic. For example, she “acted in the capacity of a nurse” despite not having any formal training in the field. At the same time, she used her position at the clinic to analyze the experiences of nearly a hundred of don Hilde’s patients. “Don Hilde,” she writes, “would not see his patients unless the person sat with me first and responded to my questionnaire.” This questionnaire included 25 questions about their education, social class, professional occupation, reasons for visiting don Hilde, and previous experiences with ayahuasca.

Anthropologists “cannot be viewed simply as studied or distanced and unproblematic representations of the cultural practices and beliefs of the others they study, but must be read as a cultural-political act in and of itself, as a literary act.”

Kim TallBear

As the anthropologist and Indigenous Science, Technology, and Society (STS) scholar Kim TallBear has written: “Ethnography and physical anthropology are translation. In that is power.” TallBear remarks that the writings of anthropologists “cannot be viewed simply as studied or distanced and unproblematic representations of the cultural practices and beliefs of the others they study, but must be read as a cultural-political act in and of itself, as a literary act.” Dobkin de Rios’ account with her father-in-law and his patients demonstrates the intertwined and uneven relationships that formed much anthropological research in settler-colonial contexts. As historians of science such as Rosanna Dent, Joanna Radin, and Warwick Anderson have shown, colonial and postcolonial relations shaped human and biological sciences research throughout the twentieth century.

Despite the power she often held when conducting her fieldwork, Dobkin de Rios’ position as a woman in the male-dominated fields of anthropology and ethnobotany in the 1960s and 1970s was marred by personal and professional challenges. For example, she recounted being told by a “gossipy colleague” that her department at Cal State Fullerton had experienced pressure to hire more women. Dobkin de Rios learned that, despite having published a book and several articles prior to completing her PhD, “there was some question” about whether she was a “serious” researcher. One of the anthropologist’s interviewers at Cal State claimed: “‘Oh no, she looks like a model, and I don’t think we have to worry about serious scholarship!’” She would go on to work there for nearly 30 years.

Discover Indigenous Reciprocity Initiative of the Americas

Complex Legacies

Marlene Dobkin de Rios’ story in “the history of plant-psychedelic use” is, indeed, a fascinating one. It demonstrates the complexities and fraught nature of conducting psychedelic research, especially for those who have been, and continue to be, marginalized or excluded.

On the one hand, she was certainly what many would call a “pioneer” in the field of psychedelic studies. Wade Davis, an esteemed anthropologist and ethnobotanist who studied under Richard Evans Schultes at Harvard, wrote that he was enchanted by her accounts and that her work guided his path in ethnobotany. And as one of the few women in this field at the time, she experienced a range of challenges and endured sexist attacks that often sought to undermine her expertise.

“Dobkin de Rios, through her expertise and family relations, wielded… power.”

On the other hand, when conducting her ethnographic research in Peru in the 1960s and 1970s, it is clear that Dobkin de Rios, through her expertise and family relations, wielded a certain power. To establish her reputation as a fortune-teller she charged her interlocutors for her services; she acquired ethnographic data from her father-in-law’s patients, who were unable to receive treatment from don Hilde until they’d spoken with the “gringa” anthropologist.

It is crucial that we recover the experiences, narratives, and accomplishments of those women who have been marginalized, or omitted, from the historical psychedelic record. However, we must go beyond merely recovery to reconstructing these histories in all their messiness and intricacy. Attending to the colonial and transnational histories that have shaped—and continue to inform—psychedelic sciences, demonstrates the tense and uneven ways through which this knowledge has been produced. The case of Marlene Dobkin de Rios is illustrative of the complexity of these histories.

Art by Marialba Quesada.

Take a minute to browse our stock:

Did you enjoy reading this article?

Please support Chacruna's work by donating to us. We are an independent organization and we offer free education and advocacy for psychedelic plant medicines. We are a team of dedicated volunteers!

Can you help Chacruna advance cultural understanding around these substances?