- Breaking Convention Conference Lives Up to Its Psychedelic Reputation - May 31, 2023

- Creating Awareness on Sexual Abuse in Ayahuasca Communities: A Review of Chacruna’s Guidelines - February 8, 2022

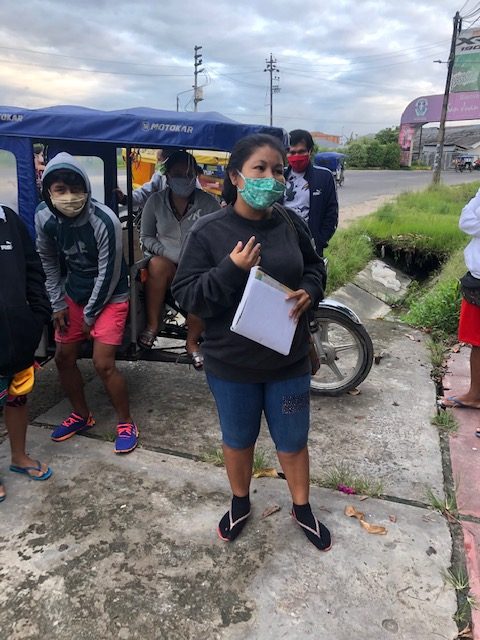

- Iquitos, Capital of Ayahuasca, Struggles During COVID - October 19, 2020

May 9th, 2020; Day 52 of quarantine; Iquitos, Peru.

Confirmed corona virus cases: 3502 Fatalities: 401

We knew it wasn’t going to be a normal day when breakfast was interrupted by the military. It was March 16, the day Peru imposed full lockdown. I was eating breakfast with my boyfriend in the local café a block from our house in Iquitos, as usual, when quarantine restrictions were enforced and businesses closed. Within the hour, the usually loud and bustling streets of the city became sparse as masked police and military officials closed cafes, restaurants, and shops and ushered people back to their houses, announcing on megaphones that quarantine restrictions had been implemented by government decree. Of course, we all knew about the coronavirus raging in the outside world but, for a while, it had seemed like it might not reach us here in the depths of the Peruvian Amazon.

So, what are the implications of the coronavirus crisis for local people, and, also, for the ayahuasca community and industry here?

Iquitos is a city in the middle of the Amazon jungle; the largest city in the world not reachable by road, and best known as the international hub of ayahuasca shamanism and shamanic tourism. Having first traveled here six years ago for my own healing, I have since been studying the development of ayahuasca shamanism as an anthropologist and advocating for safe and responsible practice as a member of Chacruna’s Ayahuasca Community Committee. So, what are the implications of the coronavirus crisis for local people, and, also, for the ayahuasca community and industry here? And, without suggesting that “ayahuasca told me” anything about the coronavirus, what wisdom might we impart from our medicine experiences and from the medicine community to better understand these uncertain times?

The Lockdown

Peru was one of the first countries to close its borders and enforce quarantine restrictions. This means that there is a strict curfew from 4pm – 4am every day and nobody is allowed out on Sundays. For a short period of time, men and women were allocated just three days each per week on which they were allowed to leave their houses, but this measure has been dropped. Only supermarkets, small convenience shops, pharmacies, the hospitals, banks, and agricultural shops were open until very recently; some food outlets now have permission to carry out deliveries and there is talk of gas and oil industries going back to work soon. Protective masks are compulsory in all public spaces. Police and military personnel are patrolling the streets to enforce restrictions. Water and gas services are also still available as usual, and, keeping the masses happy, the internet! The Government instructed internet providers that they must continue services for all customers, despite most people being unable to pay their bills currently, which, here, is usually done in person at provider shops. Despite Iquitos internet being infamously slow and unreliable, it is indeed a blessing at this time!

Yet, while some people are congratulating the government and celebrating “the best president we’ve had in at least 50 years,” others are outraged about the impact of government measures on people’s civil liberties.

Considering that Peru is a country with limited resources to handle the virus, the government acted quickly and, arguably, did the best that it could by enforcing quarantine measures pre-emptively. Yet, while some people are congratulating the government and celebrating “the best president we’ve had in at least 50 years,” others are outraged about the impact of government measures on people’s civil liberties. By government decree, police and military officials have been given powers to arrest and imprison anyone breaking the curfew, and, furthermore, to shoot anyone who resists. This has resulted in many people here being detained for 24-hour periods, some surely unfairly. An extreme example from Lima appeared in the newspaper recently of a woman who was detained after taking her trash out. Furthermore, the government announced recently that anyone caught spreading “fake news” concerning the pandemic and the resulting lockdown can be incarcerated for six years, an extreme deterrent for anyone who shows resistance to the government and what they regard as acceptable rhetoric regarding this crisis. While the atmosphere here, thus far, has remained reasonably calm, this may be in part due to the threat of serious punishment for disobeying the restrictions.

Loreto is one of the worst-hit regions with some of the worst mortality rate across the country.

Undeniably, enforcing early quarantine was initially effective in keeping the virus from spreading, but the situation is changing rapidly and, as lockdown is extended, there is widespread concern about the impact of the measures on people’s livelihoods and access to supplies, as well as the general health scare . As of May 9, there have been 65,015 confirmed cases in Peru and 1,814 deaths from the virus. In the Loreto region, where Iquitos is based, there have been 3502 confirmed cases, with 401 fatalities, so far. The situation has escalated during the past couple of weeks and it is clear, as the number of virus cases rises rapidly here and across Peru, that it has not yet reached the peak of its impact. Loreto is one of the worst-hit regions with some of the worst mortality rate across the country. The region is struggling to cope with the impact of the virus: morgues are overflowing with bodies stacked in bin bags; one hospital has closed while work to complete the building of a new one is rushed, and workers and medical staff have been flown in from Lima to assist. The main problem here seems to be the lack of oxygen required for treatment. Gladly, however, church and charity initiatives in Iquitos have managed to raise enough money to build two new oxygen plants, which will be constructed within a couple of weeks, and provide further support and relief aid to vulnerable populations, including the elderly and people living with HIV and AIDS.

It seems likely that the recent increase in coronavirus cases is due to other measures being taken to address the economic problems caused by the closure of businesses and resulting unemployment. As a measure of financial support, the Peruvian Government has provided corona virus bonuses for those with limited resources. While the support is necessary and welcomed, this means that, on certain days, the streets are filled with literally thousands of people queuing for several hours from early morning to collect their bonuses from the banks. Queues for ATM machines are similarly extortionate and, during rainstorms, people have squashed together to find cover, completely disregarding social distancing. Supermarkets and markets are busier than they would usually be. This, of course, all has the unfortunate side effect of increasing the risk of infection. Perhaps a more organized system, allocating bonus collection days based on national identity numbers, would be more effective, or, as many people here are suggesting, reopening other businesses on a limited basis to reduce customer traffic and provide income.

Indeed, economic stability is a major concern, as is the availability of basic supplies. The threat of social unrest is very real should conditions worsen. Many people face losing their livelihoods, as some businesses will struggle to survive the quarantine period that, according to a government source, is expected to continue into June, with high-risk businesses, such as clubs, restaurants, and bars, potentially shut until the end of the year. There is also widespread worry about the longer-term impact of the restrictions on access to necessities, especially as Loreto is a relatively isolated region of the world. As of yet, there seem to be sufficient supplies in the city but supplies are dwindling, especially in rural areas. The government has promised to secure food and medical supplies and is apparently delivering food packages to some communities and people unable to get to shops. However, not everyone in need has been able to access this aid. This includes some local Shipibo communities and homeless people, of which there are many here, who are struggling greatly with no services available to them. My partner and I recently launched a campaign to raise money for supplies to help vulnerable groups in the area to survive the lockdown. The tourism industry—a large part of which is ayahuasca-related—is one of the main sources of income here on which these groups depend, and from which many of us as foreign residents or visitors to this region have benefitted greatly. The long-term continuation of these practices may also be at risk.

Impact on the Ayahuasca Community

What I refer to as the “ayahuasca community” or “medicine community” in Iquitos comprises local and Western curanderos and their apprentices, healing center owners, retreat facilitators, retreat and ceremonial participants, and the many other people living here, or returning visitors who are working and partaking in ayahuasca shamanism and related shamanic practice in the region.

The lockdown came unexpectedly, with immediate impact, leaving many Western tourists stranded at ayahuasca centers in the region. In some cases, ceremonies have continued for guests and workers, providing a unique experience of quarantine. However, food and medical supplies are more limited in these more remote areas, which, inevitably, has been worrying for those stranded. Western embassies have worked hard to organize flights to repatriate stranded tourists and, as far as I am aware, have been successful in also rescuing those who were left out at centers, some of whom reported detecting “anti-gringo” sentiments from locals in the communities where they were based. We have also experienced this, at a minor level, in the city center, where some local people keep their distance more than usual from Westerners and present signs of fear when “gringos” are in their vicinity. This is assumedly due to perceived connection of the virus with foreigners. Understandably, these anti-gringo sentiments harken back to the rapid spread of illnesses brought by invaders since the colonial era.

Thus, considering that travel to the region will be restricted long-term, those dependent on ayahuasca-based trade here may be some of the most badly affected.

In the longer term, upcoming ayahuasca retreats have been canceled and some retreat centers have already planned long term closures. The Temple of the Way of Light, for example, which is one of the largest and most popular retreat centers in the region and the world, has announced it will be closed for no less than six months. Retreat centers provide much employment for locals in the region and, furthermore, there is a lot of ayahuasca-related trade here that has, and will be, further affected by the loss of ayahuasca-motivated travel to the region. This includes restaurants and the local artisania community, encompassing indigenous Shipibo artists and sellers. Thus, considering that travel to the region will be restricted long-term, those dependent on ayahuasca-based trade here may be some of the most badly affected. It is difficult to imagine what the future holds for these people and practices.

Yet, amid the fears and real problems created by this crisis, there is also a lot of hope.

There is positivity here, among those involved in ayahuasca and related medicine practice, about the impact of the lockdown on the environment due to the lack of pollution currently “giving Mother Nature time to breathe.” This is good news for the sustainability of medicinal plants. Concerns have increased here in recent years, particularly about the sustainability of ayahuasca and chacruna (the main ingredients in the ayahuasca brew), which has been threatened by the tourism industry. Availability and quality are noticeably dwindling as prices rise. This break in tourism may allow time for ayahuasca, chacruna, and other medicinal plants to grow un-impinged by human supply and demand markets. Perhaps this is nature’s way of restoring the balance.

It seems that all of us connected with the psychedelic and plant medicine community are blessed to have the teachings from past as well as present experiences to help us through these times. Specifically, plant medicines may help us with acceptance of the conditions we find ourselves in during quarantine, whatever they may be; feeling connected, despite isolation; dealing with fear and difficult emotions; facing the reality of death and, as many people across spiritual communities are commenting, this is an opportune time for personal spiritual development, integration and reflection, be it through plant medicines or other practices: “If you can’t go outside, go inside.” Yet, we must be careful not to fall into spiritual passivity and the dismissal of the real suffering in our midst.

It is crucial during this crisis that we do what we can to support Amazonian communities from which we have gained so much.

This crisis may indeed be the divine work of Nature, creating conditions in which nature itself can flourish and creating an opportunity for spiritual growth. Yet, the sad reality is that many of the people and cultures that have facilitated this spiritual growth for Western people, by sharing their knowledge and traditional healing practices, are experiencing serious deprivation and are at risk of losing their lives as well as their livelihoods. It is crucial during this crisis that we do what we can to support Amazonian communities from which we have gained so much. We must help these people and their cultures and practices to survive.

To donate to the COVID-19 Iquitos Relief Fund please follow this link.

Art by Mariom Luna.

Take a minute to browse our stock:

Did you enjoy reading this article?

Please support Chacruna's work by donating to us. We are an independent organization and we offer free education and advocacy for psychedelic plant medicines. We are a team of dedicated volunteers!

Can you help Chacruna advance cultural understanding around these substances?