- Introduction to Women and Psychedelics - July 26, 2024

- Global History of Psychedelics: A Chacruna Series - October 4, 2023

- Can Psychedelics Promote Social Justice and Change the World? - August 30, 2021

Clinical trials today recognize the need to include sex variables in research, and the gendered differences in medical research continue to influence how scientific data is created and communicated. Recognizing sex differences in drug trials is nothing new, even though historically there are examples where overlooking the need to evaluate effects in men and women independently have produced major blind spots and introduced health risks. One case that readily comes to mind is Thalidomide, which was and remains an effective medication in cancer, skin disorder, and other treatments, but when taken during pregnancy increases risks of miscarriage and growth malformations. Drug trials today recognize the need to consider sex, or biological origin, but gender—the self-representation, expression, social, and cultural views of sexuality—is more difficult to measure.

“As a historian of psychedelic drug trials, I wanted to look back at how researchers wrestled with these sex and gender-based aspects in their own studies and how or whether they considered sex and/or gender in their psychedelic research.”

As a historian of psychedelic drug trials, I wanted to look back at how researchers wrestled with these sex and gender-based aspects in their own studies and how or whether they considered sex and/or gender in their psychedelic research.

Searching for Women in Early Psychedelic Trials

Over the past decade I have been collecting, digitizing, and transcribing case reports from psychedelic experiments that took place in Canada from roughly 1950–1970. So far, I have just over 1,000 entries, coming almost exclusively from Hollywood Hospital in Vancouver, British Columbia and from three different clinical sites in Saskatchewan, including those where early proponents of psychedelics in psychiatric treatment settings, including Humphry Osmond, John Smythies, Duncan Blewett, Abram Hoffer, and Al Hubbard, worked. In these case files, women represented approximately 30% of patients. While not often explicitly spelled out, there are glimpses in the files as to gendered differences in patient or subject experiences, and examples of how gender factored into staffing considerations in the research program.

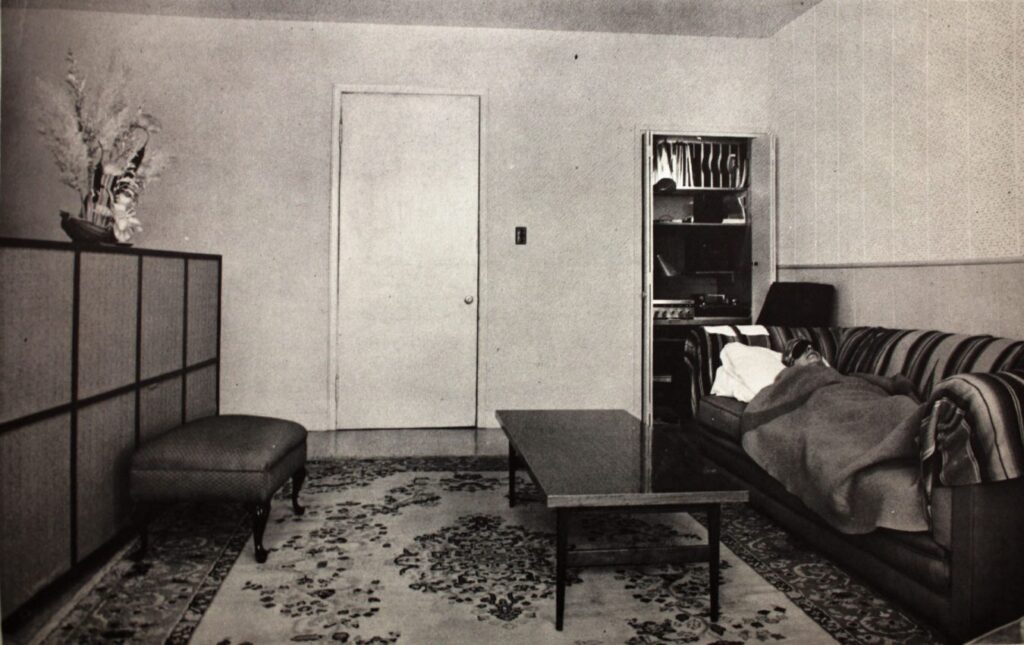

The most remarkable parts of these case files to me come from the patients or clients themselves: in cases that have a full set of notes, which admittedly are more rare than typical, we have copies of handwritten autobiographies created by patients before they undergo a psychedelic experience. Each patient was presented with a list of open-ended questions, asking them to reflect on their lives and ultimately to explain why they thought psychedelic therapy might help them. There is often a detailed “observers report” that follows, in which the exact dose of either mescaline or LSD is recorded, along with any developments in the course of the 10-hour observation period. For example, the musical selections, the physical movements or responses from the patient or subject, and the timing of the reactions. These observers reports are typically provided by a “Mrs. So and So.” Upon closer examination, those Mrs. So and Sos often seem to be wives of some of the paid staff, and in other cases they are former patients or subjects themselves. In all cases, these staff (whether paid or not) had personal experience with LSD or mescaline, which was part of the training expected for these observer positions, which over time became known as “psychedelic guides.”

In some of the subsequent reports by patients, they describe their experiences in their own words, and it is revealed that these observing women played important roles in comforting and supporting patients as they went through their own experiences. While these examples are merely anecdotal, they do offer insight into the early days of psychedelic therapy sessions and perhaps encourage us to consider how gender affected the experience, in subtle and overt ways.

Heather K.

After reading about LSD experiments in Saskatchewan through a popular magazine, Heather K. worked up the courage to inquire about whether LSD might help her. In her autobiographical statement about her experience, Heather said:

I think I regard LSD not as a cure-all, but as a partial aid in seeing myself more clearly. By taking it I would hope to make life more comfortable not only for myself but for my husband and my little daughter who is rapidly reaching an age where she is becoming more aware of the attitudes and reactions of those around her. I feel at last desperate enough to really do something about my problems instead of just thinking about them and LSD seems to offer a ray of hope. It is so difficult for me now to imagine myself any other way. In fact I think to myself rationally I want to change my behavior but do I really—have I really put any real effort into trying to change? Could I with willpower act differently, as my mother states, and does one really become bound up in a life that one is powerless to change on one’s own? Perhaps LSD can help in answering some of these questions. At the moment I do not feel that my husband could put up indefinitely with my present type of behavior. It is too hard on him as he is also a high strung type of individual. I hope therefore to try and save a few of the things which mean the most to me.

Heather’s account continued for several pages, and revealed she struggled with an obsessive-compulsive set of behaviours fixated on dirt and germs. While the specifics of her case are not generalizable, the overarching structure of her experience is more typical in these reports, whether the person is looking to understand addiction, trauma, obsession, or even sexuality. In Heather’s case, on November 14, 1964 she was admitted to Hollywood Hospital in Vancouver and given 700 milligrams of mescaline, and observed by three people—Dr. D.C. MacDonald, a psychiatrist, Frank Ogden, a self-trained therapist/guide, and Mrs. Lillian Carter—a woman described simply as “observer.”

Recordings are now available to watch here.

Mrs. Carter

Mrs. Carter is not included on the staff list. I cannot confirm that she ever received payment for her work—meaning that she may have been a volunteer—but she is not recorded in published reports. MacDonald, Ogden, and several others later appear in published reports coming from this hospital, but Carter and other women like her who appear in the observer role do not make it into these published accounts. Based on a reading of these records, in fact, it is difficult to determine what the observers did, or whether they did anything at all beyond silently observing the experiment.

But, when I search through the records produced by patients, Mrs. Carter’s name pops up periodically. This is the part of the file where patients record their own impression of the experience and its meaning to them—usually the day after their psychedelic encounter.

It turns out that Mrs. Carter appeared elsewhere in these files too, first as a subject who took LSD once (with no follow up information, as is sometimes the case with these files). But, to my surprise, she turned up in other files, not in the published accounts of the psychedelic trials or staff lists, but in the handwritten reflections produced by patients.

One patient reported feeling frightened during her mescaline experience, then wrote: “I would see Mrs. Carter and Mrs. Duke and at that time I found them friendly and it was as if they were trying to help me. I saw them bending over me and it seemed Mrs. Carter told me I was doing fine, and seeing them bent over me gave me a feeling of great solace.”

Another instance involving Mrs. Carter appeared like this to a patient: “At one point I noticed I was alone with Mrs. Carter and I asked where all the men were—I got scared—at that point I thought I must have been left alone with Mrs. Carter because of some ‘delicate feminine’ matter and I was furious—and when she said ‘You can tell me.’ I thought for sure I’d done something awful but I didn’t know what it was.”

Another woman explained: “I was consciously sick for a great deal of the time it seemed and this dropped away gradually as I saw and learned something new. Mrs Carter played the vital role here, for she actually became all faces of me as seen in the dances.”

All told, Mrs. Carter appears in over a dozen accounts, sometimes without even appearing on the accompanying staff or observer form. In many ways, she was rendered invisible in the official record, and only through the patients voice we can gain some glimpses of the work that she performed. Moreover, based on the patients’ accounts alone, her presence and attention seems to have had meaning for them, even when it is difficult to generalize or identify specific trends or interventions.

Discover Indigenous Reciprocity Initiative of the Americas

Traces of Early Psychedelic Trials

“These historical fragments of early trials spotlight the importance of good therapeutic guides.”

Given these traces of women’s work and women’s experiences in these early trials, it is heartening to learn that current efforts to train psychedelic therapists is taking these factors into account when preparing trials that include male and female therapists. Hopefully we can move past the era of burying Mrs. So and So’s contributions in the margin notes of a trial and instead invest directly in developing a more diverse set of criteria for both patients and staff to explore psychedelics in a safe and supported environment. These historical fragments of early trials spotlight the importance of good therapeutic guides, and, perhaps, help to remind us of the importance of having diverse guides in place to support diverse experiences.

Take a minute to browse our stock:

Did you enjoy reading this article?

Please support Chacruna's work by donating to us. We are an independent organization and we offer free education and advocacy for psychedelic plant medicines. We are a team of dedicated volunteers!

Can you help Chacruna advance cultural understanding around these substances?