After being diagnosed with a mental health condition, I started searching for alternatives to psychiatric medication. My pursuit led me to psychedelic-assisted therapy, a psychiatric approach developed within what proponents of psychedelics have called a “psychedelic renaissance” (Sessa, 2012). This phrase refers to the renewed scientific interest in the potential uses of psychedelics to treat mental health conditions and possibly even expand knowledge about the human mind. Surprisingly, in exploring clinical literature, I found a significant amount of research focused on psilocybin, DMT, and MDMA, and notably fewer mentions of peyote cactus—a species with a long tradition of use among some Mexican and Native American groups—and mescaline, one of the plant’s active components.

This imbalance struck me as odd seeing that these substances were the first psychedelics I had learned about when reading Aldous Houxley’s seminal book The Doors of Perception (1954). This publication, which is essential for the history of psychoactive agents, especially mescaline (Jay, 2019), was written at a moment when western clinical culture showed an overt enthusiasm for these materials for the first time. During this period, which started in the late nineteenth century and finished between the mid-1960s and 1970s with the imposition of prohibitional policies, the cactus and its alkaloid played a crucial role in psychoactive research (Dawson, 2018). Despite the centrality of “peyote/mescaline” in this early era of research, which has been called the “golden age of medicine” (Bisbee et al., 2018), these substances are not central players in today’s clinical studies (Sessa, 2012). Even if peyote is still a highly desired plant today, as the massive amount of buttons sold annually in the United States demonstrates (Bauml & Schaefer, 2016), peyote and mescaline are not widely used in current psychedelic-assisted therapy (Sessa, 2012).

what has changed since Huxley’s days that made these substances lose currency in contemporary scientific research, while remaining popular among psychedelic users?

Such a discrepancy raises the question of what has changed since Huxley’s days that made these substances lose currency in contemporary scientific research, while remaining popular among psychedelic users? An examination of relevant literature on the subject suggests that this disparity might correspond to two main points. Firstly, mescaline is less marketable than other psychedelics (Jay, 2019). Secondly, mescaline’s prevalence is affected by the increased complexity of today’s debates concerning peyote use, as they expand beyond establishing the moral validity of its consumption to encompass issues of social justice and ecological threats.

Aldous Huxley and the 1960s Psychedelic Era

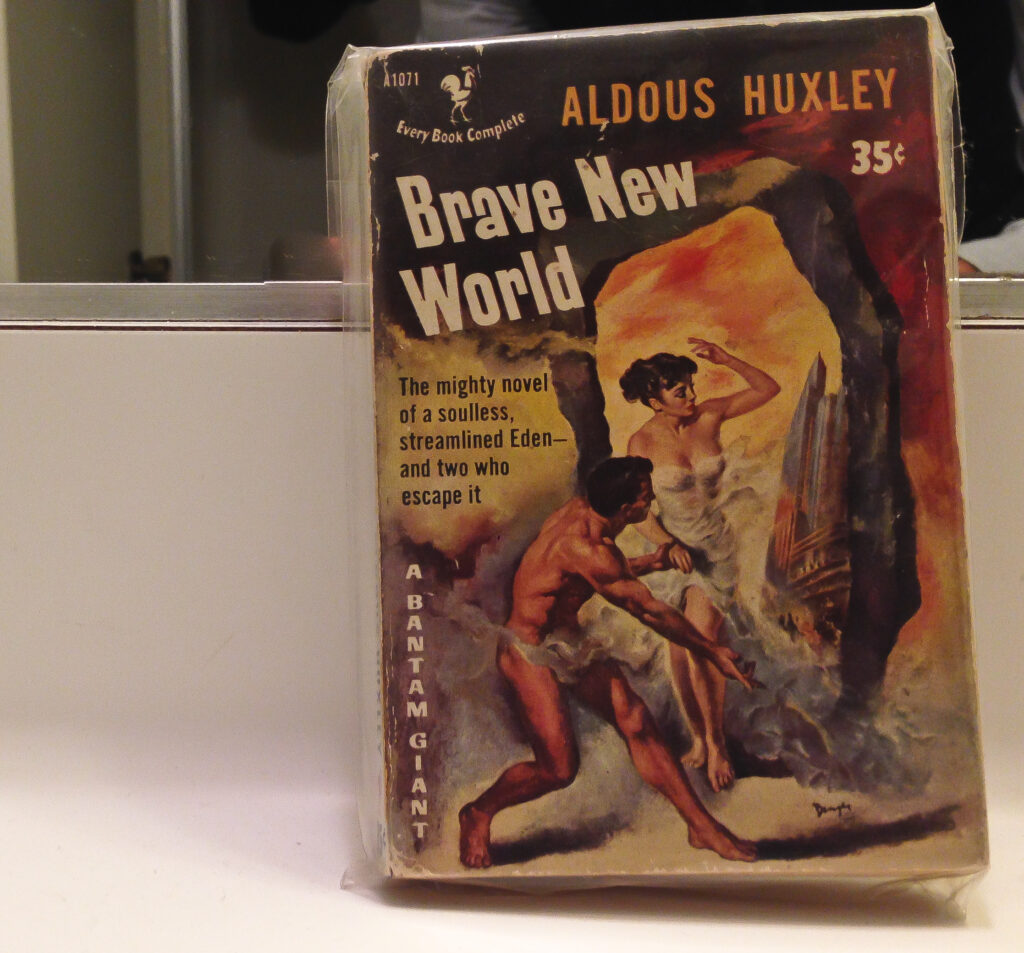

Aldous Huxley is widely known for his wide range of interests: from spirituality, philosophy, and the human mind and consciousness, to culture and science, especially biology (Bisbee et al., 2018). He jumped to fame after the publication of Brave New World in 1932, a fictional story about a dystopic society in which people are controlled through drugs. While drugs feature prominently in Brave New World, many other pieces of his writings also address drug-related issues, mainly regarding their effects on the human mind. His work is considered a vital piece of the so-called psychedelic literature (Dickins, 2012).

It is worth noting that the time when Huxley wrote The Doors of Perception was one of deep interest in psychedelics. Scientists, especially psychiatrists, were exploring these substances for their medical uses and potential to help explain and even expand consciousness. The psychiatric academic climate was one of enthusiasm, as can be read in British physician Dr. Ronald Sandinson’s words:

It was immensely exciting. We were looking for a new world. It’s hard now to recapture the excitement of those years. During the decade or so after the war we were talking about the new Elizabethan age; everything seemed possible. (as cited in Sessa, 2012, p. 56)

This tremendous excitement did not come from nowhere. Much of this psychedelic work was built on research published between the late 1890s and the early twentieth century, which was centered on peyote and mescaline.

Also known as Lophophora williamsi, peyote is a spineless cactus endemic to the southwestern United States and northern Mexico, used for centuries by Indigenous people in those regions for its spiritual and medicinal properties. Mescaline is an alkaloid derivative of peyote, identified in 1898 by Dr. Arthur Heffter as its primary psychoactive substance, and first synthesized by Ernst Späth in 1919 (Dawson, 2018). Most of these early investigations were conducted by American and European researchers seeking to make sense of the cactus and mescaline and to find commercial uses for them. However, peyote was not attractive as a pharmaceutical preparation as it did not resemble a regular medication, with the buttons having to be chewed and swallowed. On the other hand, synthetic mescaline could be injected into the patient and resembled something that could be consistently tested, making it more popular among some psychiatric circles (Dawson, 2018). This pharmaceutical mescaline used in medical contexts meant that peyote remained related to spirituality and its Indigenous uses (Dyck, 2017).

Despite some early scientific enthusiasm for peyote and mescaline, historian Alexander Dawson (2018) argues that the multiple experiments conducted in these years did not yield easy-to-sell clinical uses. Consequently, he argues that instead of continuing to explore their potential medical benefits, scientists labeled them “psychotomimetic,” a term used to refer to a substance capable of mimicking perceptual distortions similar to those experienced during psychosis. Under the psychomimetic paradigm, mescaline was relegated to a peripherical position in research, at least in the United States. However, some artists, socialites, and other enthusiasts kept experimenting with peyote—and, more frequently, with mescaline—even if these drugs had lost popularity within the medical environment.

Discover the Indigenous Reciprocity Initiative of the Americas

Huxley learned about mescaline after reading a paper co-authored by Humphry Osmond. The British psychiatrist had been recruited in 1951 by the health ministry in the Canadian province of Saskatchewan to manage its provincial mental health hospital. It is worth stressing that, as Dawson (2018) shows, these Canadian scholars did not discard mescaline as a research object as they saw its potential as a treatment for alcoholism, bringing the substance back into psychiatry’s interest. Thus, Dawson continues, Osmond got the chance to examine the effects of this substance, which he found astonishing: increased mental focus, euphoria, and self-reflexivity that made therapeutical uses possible. He even argued that a single mescaline experience could resolve the patient’s problems. However, his observations were never turned into a formal clinical protocol.

Following Huxley’s reaching out to Osmond in early 1953, the two sustained an epistolar relationship for a decade. Their letters reveal that the writer asked Osmond to visit him in California and supplied him with the alkaloid. Huxley wrote beautifully and extensively about his experience in The Doors of Perception. He described how deeply the drug affected his senses and consciousness and stressed the potential spiritual and psychological benefits of these unusual and powerful substances. Instead of referring to the mescaline’s effects as psychosis-mimicking distortions, Huxley described them as the revelatory of a deeper reality unknown to us in our day-to-day normalcy. As Ido Hartoghson (2020) has argued, Huxley’s work represents a departure from the psychotomimetic paradigm as he used his experience as the basis for philosophical exploration. The writer was so adamant about the uses of mescaline that he even came to be known as the “mescaline’s salesman,” even though its effects were not clinically assessed yet.

Aldous Huxley was so adamant about the uses of mescaline that he even came to be known as the “mescaline’s salesman,” even though its effects were not clinically assessed yet.

Even if Huxley’s book was not a bestseller, it spurred various responses, from sympathy to acute criticism. While some commentators celebrated Huxley’s idea that mescaline could be superior to alcohol, others complained that his grand ideas were mere fantasies or expressed consternation for the possibility that the book encouraged youth to experiment with drugs. One outstanding criticism was made by the eminent psychiatrist Carl Jung. The psychoanalyst dismissed Huxley’s claims, arguing that there was no point in trying to know more about the unconscious than what dreams and intuitions can reveal (Siff, 2015). Notably, behind Jung’s criticism was a recurring idea that framed the artificial experiences created by psychoactive drugs as immoral (Hartogson, 2020). The question of whether consuming mescaline was an immoral practice seems to be central to the 1960s debate about its use. In addition, the substance lacked clinical validation, as the experimental research on it was early abandoned in favor of other compounds—mainly LSD—which had similar effects at lower doses (Jay, 2018). On the other hand, peyote was not included in this debate as it was strongly associated with its Indigenous origins. As historian Erika Dyck explains:

Peyote and ayahuasca had cultural reputations linking them with Indigenous healing or spirituality, which added to the mystique of the exotic mind-manifesting experience. LSD, and mescaline (when separated from the peyote cactus), had reputations as products of scientific laboratories but were nonetheless substances that could inspire spiritual and ontological explorations (Dyck, 2017).

Peyote/Mescaline and the Psychedelic Renaissance

As Dyck contends, contemporary psychedelic research shares common ground with these historical developments: “enthusiasm and awe, and hyperbolic claims about the drug’s potential impact on a wide range of medical concerns” (2017). She suggests that assessing these potentially exaggerated claims requires attention to the same epistemological problems and pitfalls that research has dealt with in the past. Dyck’s observations are also accurate when talking about the consumption of peyote and mescaline. Even if the moral validity of the consumption of these substances is not at the core of today’s debates, there remains little discussion about how they might work in a clinical context. The limited quality of this discussion seems to be inherited from the mid-century’s idea about the low marketability of these substances. Thus, the use of mescaline and peyote in the context of psychedelic-assisted therapy today has not yet regained the same level of exploration it had during Huxley’s era, at least in the psychiatric realm.

The use of mescaline and peyote in the context of psychedelic-assisted therapy today has not yet regained the same level of exploration it had during Huxley’s era, at least in the psychiatric realm.

Besides, the diversification of voices in the contemporary political realm has shed light on how the extensive use of peyote might be problematic. In other words, in addition to the preoccupations already present in the first half of the twentieth century, today’s psychedelic renaissance raises new questions and challenges for the use of mescaline and, especially, peyote. First, it must be said that, in contrast to the 1960s psychedelic era, the twenty-first century psychedelic renaissance is witnessing the increasing popularity of practices such as microdosing and alternative retreats to other informal encounters with psychedelic substances. Such proliferation has fostered the growth of a psychedelic industry that promotes the commodification of peyote and other sacred plants (Negrin, 2020). Part of this industry is the emergence of drug tourism, especially in Latin America, based on “claims of religious, ceremonial, and healing benefits” (Dyck & Elcock, 2022). The rapid expansion of such an industry has raised important questions about colonialism, cultural property (Negrin, 2020), and ecological sustainability (Ermakova, 2020) that cannot be ignored.

Conclusion

It is impossible to deny the common ground between the 1960s psychedelic era and today’s psychedelic renaissance, especially the intense interest and wonderment around these substances’ potential to delve into different dimensions of the self and connect with nature and others. Aldous Huxley played a part in disseminating these ideas, as his writing was central in bringing attention to psychedelics and their potential benefits in the Western world. Despite widespread interest in peyote and mescaline, it is still unclear how these particular psychedelics would work in a clinical context. Besides, in contrast to Huxley’s era, peyote use today raises questions about the ecological sustainability of this species, its commodification, and whether non-Indigenous people should be entitled to use it. For these reasons, much work must be done before integrating mescaline, especially peyote, into psychedelic-assisted therapy.

Art by Mariom Luna.

References

Bauml, J., & Schaefer, S. (2016). Preface. In Labate, B. C., & Cavnar, C. (Eds.). Peyote: History, tradition, politics, and conservation. (pp. xi–xu). ABC-CLIO.

Bisbee, C. C., Bisbee, P., Dyck, E., & Patrick, S. S. J. S. S. (Eds.). (2018). Psychedelic Prophets: The Letters of Aldous Huxley and Humphry Osmond. McGill-Queen’s Press-MQUP.

Dawson, A. S. (2018). The Peyote Effect. In The Peyote Effect. University of California Press.

Dickins, R. J. (2012). The Birth of Psychedelic Literature: Drug Writing and the rise of LSD Therapy 1954–1964. University of Exeter.

Dyck, E. & Elcock, C. (Eds.). (2022). Introduction: Global history of psychedelics. MIT University Press.

Dyck, E. (2017). A Psychedelic Renaissance – Will we avoid tripping this time? Hidden Persuaders http://www7.bbk.ac.uk/hiddenpersuaders/blog/psychedelic-renaissance/

Ermakova, A. (2020, May 12). A word in edgewise about the sustainability of peyote. Chacruna Institute. https://chacruna.net/a-word-in-edgewise-about-the-sustainability-of-peyote/

Hartogsohn, I. (2020). American trip: set, setting, and the psychedelic experience in the twentieth century. MIT Press.

Negrin, D. (2020). Colonial Shadows in the Psychedelic Renaissance. In Labate, B. C. & Cavnar, C. (Eds.). Psychedelic Justice. Towards a diverse and equitable psychedelic culture. Synergetic Press.

Sessa, B. (2012). The psychedelic renaissance: Reassessing the role of psychedelic drugs in 21st-century psychiatry and society. Muswell Hill Press.

Siff, S. (2015). Acid hype: American news media and the psychedelic experience. University of Illinois Press.

Take a minute to browse our stock:

Did you enjoy reading this article?

Please support Chacruna's work by donating to us. We are an independent organization and we offer free education and advocacy for psychedelic plant medicines. We are a team of dedicated volunteers!

Can you help Chacruna advance cultural understanding around these substances?