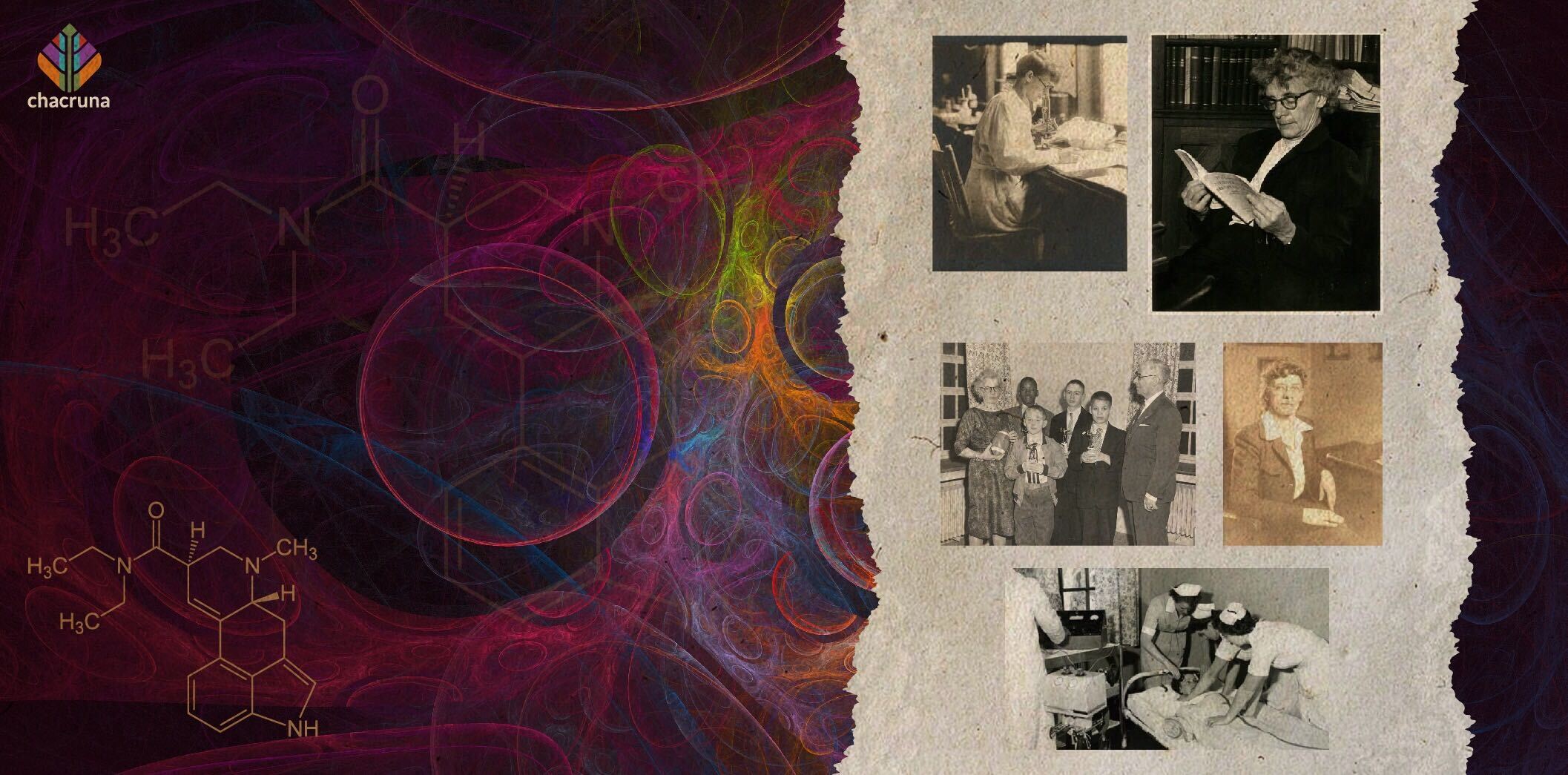

- Lauretta Bender: Seminal Psychiatrist & Forgotten Psychedelic Pioneer - April 29, 2021

- Nina Graboi, A Forgotten Woman in Psychedelic Lore - October 21, 2020

As historians gradually shed more light on women’s perspectives in the rich history of psychedelics, we are slowly beginning to see the underappreciated role women played in the rise of psychedelic science in the postwar era. Unsurprisingly, very few women were official members of the research teams (never mind team leaders) in major hospitals and universities, and they were almost never credited for the thousands of scientific publications that resulted from research into LSD and other psychedelics. The cultural climate of the time, which confined women to the sphere of domesticity and gendered stereotypes, was largely responsible for this imbalance.

Notwithstanding Betty Eisner, whose work has finally been chronicled and placed alongside the research of Sidney Cohen and Timothy Leary, a notable and virtually undocumented exception to this trend is Lauretta Bender. Her story is fascinating not just because she is yet another woman whose psychedelic legacy has been obscured by other narratives, but because it reveals a series of triumphs against adversity that led to her rise as a maverick and highly regarded psychiatrist.

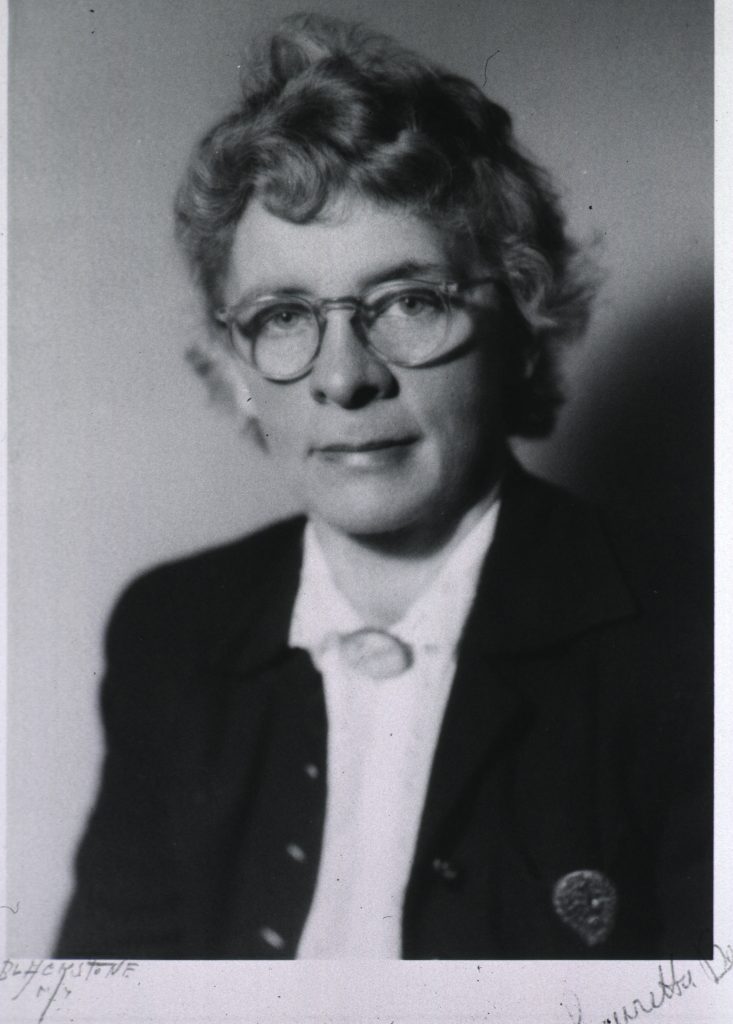

Bender’s childhood suggested anything but a fantastic career in medicine. Born in 1897 in Butte, Montana, she experienced serious difficulties at school to the point where she repeated her first grade three times. Her teachers concluded that she was mentally deficient, but it turned out that she was merely, if acutely, dyslexic. Fortunately, her father recognized that she was an extremely bright child with learning difficulties who needed empathetic support instead of punishment. His strong faith in his daughter was well justified and years later Bender underscored how critical this intervention was: “Had my father not been superintendent of public instruction during my grammar school years, I doubt that I would ever have graduated.”

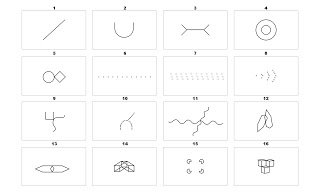

Bender showed how wrong her instructors had been by going on to study medicine at the University of Chicago and receiving her MD at the University of Iowa in 1926, at a time “when it was rare for women to be physicians.” Subsequently she remained keenly interested in the study of reading and writing disorders and arguably her greatest legacy is the Bender-Gestalt Test (also known as the Visual Motor Gestalt Test), a widely used tool she developed to diagnose learning difficulties among children. Her approach to the issue was radically innovative, as noted by psychologist Rosa Hagin: “At a time when learning problems were frequently dismissed as minor symptoms of emotional disturbance, she placed them in a neurodevelopmental context, devised examination methods that have won universal acceptance, and recognized and valued the contribution that teaching made in remediation.”

“At a time when learning problems were frequently dismissed as minor symptoms of emotional disturbance, [Lauretta Bender] placed them in a neurodevelopmental context, devised examination methods that have won universal acceptance, and recognized and valued the contribution that teaching made in remediation.”

Rosa Hagin

Between 1929 and 1930, Bender conducted research into schizophrenia at Johns Hopkins by studying 90 women diagnosed as such. Many of the subjects were mute and Bender developed non-verbal ways of communication that she continued to use in her subsequent work. Moreover, she became a well-respected authority on the study of autism, even though her legacy has been obscured by Leo Kanner’s 1943 paper, which is often referred to as the seminal article that turned autism into an identifiable clinical syndrome. In fact, Kanner and other experts in the field frequently looked to her expertise on the matter, and it was Bender who first called childhood schizophrenia (which was often the name given to autism back then) a pathology of the central nervous system.

In 1930, Bender began working at Bellevue Hospital in New York City and a few years later she became the first director of the children’s inpatient ward. A guiding principle to her supervision was the maximization of child welfare and the creation of a supportive learning environment for them. Teachers were recruited as part of the medical team and implemented in-hospital tutoring services for children with language issues. Such provisions are nowadays taken for granted, but by the standards of the time they were groundbreaking.

During her time at Bellevue, she used amphetamines to treat children suffering from hyperkinesia and other forms of mental illness. She had posited that the illness stemmed not from increased motor activity or physical energy but rather from a problem of perceptual disorganization, including self-image concepts. In the 1940s, Bender and her team found that amphetamines were effective in the treatment of hyperkinesia as well as narcolepsy and sexual problems among children under the age of 13.

Bender’s stellar career and pioneering accomplishments have granted her a special place in the history of psychiatry, as illustrated by some of her peers’ superlative praise in The Women of Psychology (1982) a few years before her death in 1987: “Lauretta Bender undoubtedly has been the preeminent woman psychiatrist of the second half of the twentieth century. There is some justification for naming her the preeminent living psychiatrist in the world, period.” What is less known about Bender, and that further illustrates the incredible breadth of her contribution to psychiatry, is her research into psychopharmacology and in the use of psychedelics to treat mental illness.

Support the Eagle and the Condor’s Ayahuasca Religious Freedom Initiative

In 1956, she was appointed Director of Research of the newly created children’s unit at Creedmoor State Hospital in Queens in 1956. Five years later she was among the few physicians to begin treating children with mental illness by giving them psychedelics. Around that time, she discovered LSD and as someone subject to migraines she used the drug to treat her condition and “found it a very effective preventive.”

Initially, Bender and her colleagues struggled to win approval of the New York State Commissioner of the Department of Mental Hygiene, Paul Hoch. Hoch balked at the prospect of provoking a temporary psychotic episode, which was the prevailing theory of what the psychedelics were doing, as a method of therapy, until Bender, citing prior work, convinced him that by inhibiting serotonin, LSD would increase responsiveness to sensory stimulation along with skeletal and muscle activity.

Bender’s team started with low doses of 25 µg (micrograms) on mute children and children diagnosed with autism and schizophrenia between 5 and 11 years of age. They found that the majority of them were subsequently able to interact with the medical staff and engage in motor play, which was accompanied by improvements in well-being and elevated mood. They gradually increased the dosage until they reached 150 µg per day and noted “an improvement in their general well-being, general tone, habit patterning, eating patterns and sleeping patterns” within the autistic population, while some children improved their vocalization. The boys diagnosed with schizophrenia (without autism) “became more insightful, more objective, more realistic” even though they soon became depressed because they realized that they were in a hospital cut away from their families.

Discover Indigenous Reciprocity Initiative of the Americas

Bender and her colleagues came to similar “normalizing” results using psilocybin and the more obscure methysergide, better-known as UML-491 and marketed by Sandoz Pharmaceuticals as Sansert, for the treatment of migraines. By 1965, however, there were mounting controversies surrounding psychedelic drugs and Sandoz, the patent holder of LSD, ceased its distribution to protect its brand image. Her team did not turn to the National Institute for Mental Health for supplies because by then there were (unfounded) rumors linking LSD with irreversible chromosome damage. Three years later, her last known involvement with psychedelic science was to publish a paper that did not corroborate those reports, after closely examining their eight-nine child subjects.

Lauretta Bender “purposefully withdrew from the debates surrounding LSD in order to protect herself and preserve her reputation as a medical doctor, even though in private she was very enthusiastic about psychedelics.”

According to parapsychologist Stanley Krippner, Bender purposefully withdrew from the debates surrounding LSD in order to protect herself and preserve her reputation as a medical doctor, even though in private she was very enthusiastic about psychedelics—tellingly, she had read Huxley’s Doors of Perception (1954) and was using the word psychedelic by 1966. In this respect, it is worth noting that in spite of the 1970 federal prohibition of these drugs she managed to have her New York State license to acquire and administer psychedelics renewed in 1971.

What Lauretta Bender did with that license is a matter of speculation, but in any event further, in-depth historical research may be warranted to answer this question and shed more light on Bender’s role in pioneering the treatment of children’s autism with psychedelics, at a time when anecdotal evidence suggests that she undertook significant psychedelic research in the 1960s.

Art by Marialba Quesada.

Take a minute to browse our stock:

Did you enjoy reading this article?

Please support Chacruna's work by donating to us. We are an independent organization and we offer free education and advocacy for psychedelic plant medicines. We are a team of dedicated volunteers!

Can you help Chacruna advance cultural understanding around these substances?