About the Toad

Incilius (formerly known as Bufo) alvarius, or Sonoran Desert toad, is native to the Southwest of the USA and northwest of Mexico, inhabiting, as its name hints, the Sonoran Desert. This is the largest native toad species in the USA, reaching up to 20 cm in length. Other distinctive features are: a white wart at each corner of the mouth, prominent cranial crests, large and elongated glands behind their eyes, relatively smooth skin in olive-green-grey color, with pale white belly.

Sonoran Desert toads are active from late May to September, principally during the summer rainy season. For the rest of the year, they hibernate underground. During the hot summer months, they are nocturnal and spend days in the shaded underground burrows where it is dark and cool. They prefer to live near permanent water sources, although they can be occasionally found in semi-arid grasslands or even woodlands. I. alvarius eats pretty much anything it can catch: a variety of insects, lizards, rodents, and even small venomous snakes or scorpions.

Toad mating season is triggered by the onset of rains (even in captivity, these toads need the stimulation of falling water to start mating). The males’ call is not particularly loud for a toad this large, and sounds like a hoot or a whistle. They mate in the water; either temporary rain pools or permanent ponds. Females lay thousands of eggs in long, sticky strands and males fertilize them externally. Tadpoles metamorphose after 6 to 10 weeks. If conditions are right, individuals can reach sexual maturity after one season. This species lives at least 10 years, and perhaps as many as 20 years.

Like most members of the Bufonidae family, Sonoran Desert toads have toxin glands behind their eyes, called parotoid glands, that secrete a milky substance, protecting the toad from predators. Additional glands are located on the legs. These secretions (colloquially and erroneously known as “toad venom”) contain various toxins, such as cardiac glycosides, bufotenine, and the remarkably powerful psychedelic tryptamine 5-MeO-DMT. Other components in toad secretions are serotonin; catecholamines, such as adrenaline and noradrenaline; and noncardioactive sterols, such as cholesterol, provitamin D, gamma sitosterol and ergosterol (Chen & Kovaříková, 1967).

Join us at Sacred Plants in the Americas II

Although many other toads have toxic gland secretions, and several species contain bufotenine, Incilius alvarius is the only known toad species to also have 5-MeO-DMT. The 5-MeO-DMT content of toad venom ranges from 15% of 5-MeO-DMT in the earlier studies (Erspamer et al., 1967; Weil & Davis, 1994) to 25–30% 5-MeO-DMT in a more recent investigation, with about 200–300 mg of 5-MeO-DMT per 1g of dry secretions (Uthaug et al., 2019).

History of Toad Use

The current “toad medicine circles” are thought to be a relatively recent phenomenon, tracing its origin to the publication of a booklet, Bufo alvarius: The Psychedelic Toad of the Sonoran Desert, in 1984.

Although it was initially proposed that I. alvarius toad secretions have long history of use (Weil & Davis, 1994), there is no conclusive evidence either from archaeological, literary, or ethnographic sources for the indigenous use of these toads for their psychoactive properties (Ott, 1996; Horak et al., 2018; Cortina, 2018). The current “toad medicine circles” are thought to be a relatively recent phenomenon, tracing its origin to the publication of a booklet, Bufo alvarius: The Psychedelic Toad of the Sonoran Desert, in 1984. The author, under the pseudonym “Albert Most,” was the founder of the Church of the Toad of Light and pioneered spiritual use of the toad “venom.” He laid out detailed instructions on how to “milk” the toads and then smoke their gland secretions (Most, 1984). In the recent season of Hamilton’s Pharmacopeia, Hamilton Morris uncovered the real identity of Albert Most. For several decades, 5-MeO-DMT remained a relatively obscure psychedelic, but now is becoming increasingly popular in a variety of settings; from some Indigenous communities in Mexico to the increasing popularity of “toad medicine” circles and recreational use (Davis et al., 2018; Uthaug et al., 2020).

Discover Indigenous Reciprocity Iniciative of the Americas

Conservation Issues

There is an alarming global decline in amphibian species due to habitat loss, pesticides, pathogens, and climate change (Hayes et al., 2010). Calculations based on extinction rates suggest that the current extinction rate of amphibians could be 211 times greater than the background rate. A particularly notorious pathogen devastating amphibian populations worldwide is chytrid fungus. Out of 7800 species of amphibians, it has already wiped out 90 species entirely and caused drastic population decline in 501 more species. Chytridomycosis is affecting hundreds more species, although it is less deadly for amphibians in warmer climates (Scheele et al., 2019). I. alvarius populations in Arizona have already tested positive for the chytrid fungus (Sigafus et al, 2014).

In the USA, I. alvarius are presumed extirpated in California, endangered in New Mexico, and considered vulnerable in Arizona (NatureServe, 2021). In Mexico, they are found in the northern part of Baja California, and in Sonora and northwest Sinaloa. There are plans for an up-to-date monitoring program supported by the re-issue of A. Most’s booklet. Although the International Union for Conservation of Nature lists this species as of “least concern,” the lowest category of risk, the latest assessment was done in 2004 (IUCN, 2021), and very likely does not reflect the reality of the current situation.

Due to the presence of bufotoxins, very few animals attempt to catch or kill these toads. There are documented cases of badgers, and garter and indigo snakes eating them, but mostly it’s raccoons and humans that they have to beware of. Raccoons can easily flip the toads over and bite into their belly, unharmed by the parotoid glands. Increasing urbanization and development means an increasing number of toads come into direct contact with humans and their pets. For pets like dogs, an encounter with this toad can be lethal.

Huge numbers of toads are killed while crossing highways to reach breeding pools, or when hanging out in the well-lit areas on the roads catching insects attracted by street lights.

Another problem brought up by development is the ever-increasing network of roads and highways. Huge numbers of toads are killed while crossing highways to reach breeding pools, or when hanging out in the well-lit areas on the roads catching insects attracted by street lights. According to Robert Villa, the president of the Tucson Herpetological Society, roads are a “mortality sink” where “source-sink dynamics” are evident; toads congregate near the roads, and as these toads die or are relocated, other toads from nearby areas take their place, creating an illusion of abundance, while in fact, there is depletion in the neighboring areas.

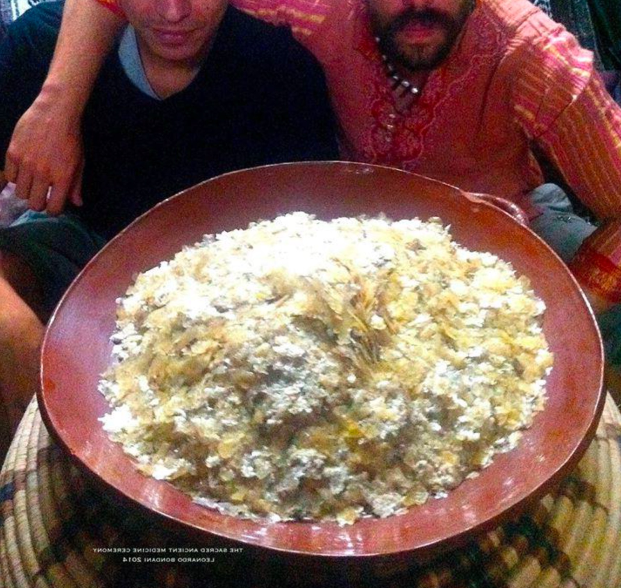

And now, with the increasing popularity of toad secretions as a psychedelic, toads are caught and their gland secretions are collected, often in huge quantities, to supply a growing number of retreat centers and “toad medicine” circles (see the photo below). Toad secretions are actively promoted as a treatment for a number of mental health problems.

Although “milking” the toads and subsequently releasing them does not directly result in their mortality, it is a stressful event that deprives them of their protection and can be harmful. Stress can negatively influence reproduction, immune function, and growth (Walls & Gabor, 2019), and, if accompanied by relocation of the toads to a different place from where they were collected, might well be fatal.

Although “milking” the toads and subsequently releasing them does not directly result in their mortality, it is a stressful event that deprives them of their protection and can be harmful. Stress can negatively influence reproduction, immune function, and growth (Walls & Gabor, 2019), and, if accompanied by relocation of the toads to a different place from where they were collected, might well be fatal.

What Are the Alternatives?

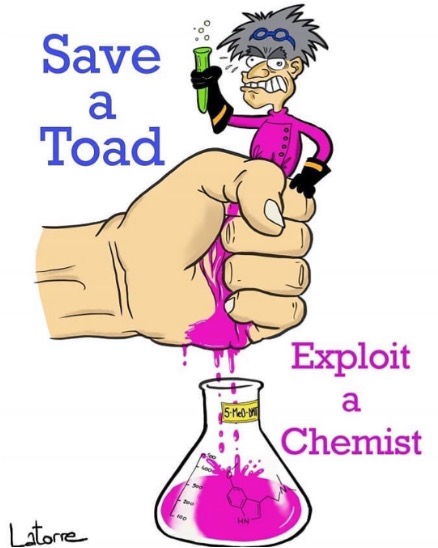

A pure compound of 5-MeO-DMT is easily synthesized (e.g., Sherwood et al., 2021) and there is a large number of plants that contain 5-MeO-DMT (often alongside bufotenine and DMT, e.g. Anadenanthera, Virola spp. and many others), something that does not require any toad harassment.

A pure compound of 5-MeO-DMT is easily synthesized (e.g., Sherwood et al., 2021) and there is a large number of plants that contain 5-MeO-DMT (often alongside bufotenine and DMT, e.g. Anadenanthera, Virola spp. and many others), something that does not require any toad harassment. Another ethical option is to collect toad secretions from toads killed by motor vehicle collisions.

Support the Eagle and the Condor’s Ayahuasca Religious Freedom Initiative

Second, from the scientific point of view, pure 5-MeO-DMT is considerably safer; one can easily measure the exact dose, while the amount of 5-MeO-DMT varies in the toad secretions. Even the number of different alkaloids varies in the toad, and it might be that not all of the toxic ones are neutralized by smoking or vaporization. 5-MeO-DMT is the only psychoactive alkaloid present in sufficient quantities to have an effect. Moreover, the evidence so far points to the fact that 5-MeO-DMT is responsible for reported positive effects: improvements in mindfulness capacities, mood, and well-being were observed in people, irrespective of whether they used pure 5-MeO-DMT or toad secretions (Uthaug et al., 2019, 2020; Davis et al., 2019). Of course, for certain users with their own cultural or spiritual beliefs, the toad (and its natural secretions) is what is valued and appreciated, though there is not much research about this.

Although Incilius alvarius can be kept and even bred in captivity, it is fairly difficult to establish optimal living conditions to ensure a good quality of life for these animals unless one is experienced with amphibians. Moreover, captive toads are more hesitant to secrete toxins than the wild ones, so it would be necessary to stress the toads even more.

Conclusion

Although compared to ever-increasing juggernauts of habitat loss, development, climate change, and pathogen spread, toad “milking” is arguably a lesser problem, additional damage thus inflicted may well be “the last straw” that challenges the survival of these unique species, particularly if the demand continues to increase. Conservation biology is often a crisis discipline, with measures taken when the damage is already too great. This is a case where we have a chance to act before irreversible damage is achieved.

It is necessary to reflect whether one’s own consciousness expansion or potential benefit is worth the stress and suffering of another being.

Sign up to our Newsletter:

Some believe that even talking about plants or animals facing serious problem in the wild could increase demand, but I think that providing accurate information is a much better option. It is necessary to reflect whether one’s own consciousness expansion or potential benefit is worth the stress and suffering of another being. I believe that many people, once they become aware of how harmful and disturbing collecting toad secretions is to wild toads, would choose different, more ethical and sustainable alternatives. In conclusion, I’d like to echo Malin Uthaug: “My hope and wish for the future is that all of us, be it consumers, researchers, organizers, or facilitators, will think twice about whether experiencing 5-MeO-DMT at the expense of a species’ continued presence on this planet is worth it.”

Art by Mariom Luna.

References

Chen, K. K., & Kovaříková, A. (1967). Pharmacology and toxicology of toad venom. Journal of pharmaceutical sciences, 56(12), 1535–1541.

Davis, A. K., So, S., Lancelotta, R., Barsuglia, J. P., & Griffiths, R. R. (2019). 5-methoxy-N, N-dimethyltryptamine (5-MeO-DMT) used in a naturalistic group setting is associated with unintended improvements in depression and anxiety. The American journal of drug and alcohol abuse, 45(2), 161–169.

Davis, A. K., Barsuglia, J. P., Lancelotta, R., Grant, R. M., & Renn, E. (2018). The epidemiology of 5-methoxy-N, N-dimethyltryptamine (5-MeO-DMT) use: Benefits, consequences, patterns of use, subjective effects, and reasons for consumption. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 32(7), 779–792.

Erspamer, V., Vitali, T., Roseghini, M., & Cei, J. M. (1967). 5-Methoxy-and 5-hydroxyindoles in the skin of Bufo alvarius. Biochemical pharmacology, 16(7), 1149–1164.

Hayes, T. B., Falso, P., Gallipeau, S., & Stice, M. (2010). The cause of global amphibian declines: A developmental endocrinologist’s perspective. Journal of Experimental Biology, 213(6), 921–933.

Horák, M., Segovia, E. M., & Bello, A. C. (2019). Bufo alvarius: Evidencias literarias y controversias en torno a su uso tradicional { Bufo alvarius: Literary evidence and controversies around its traditional use]. Medicina naturista, 13(1), 43–49.

Gutiérrez-González, C. E., Gómez-Ramírez, M. A., Gutierrez-Garcia, D., Valenzuela, J., Rorabaugh, J. C., & Flesch, A. D. (2016). Interactions between Sonoran Desert toads (Incilius alvarius) and mammalian predators at the Northern Jaguar Reserve, Sonora, Mexico. Sonoran. Herpetologistl, 29,(2), 26–27.

Ott, J. (1996). Pharmacotheon: Entheogenic drugs, their plant sources and history. Kennewick, WA: Natural Products Company.

Scheele, B. C., Pasmans, F., Skerratt, L. F., Berger, L., Martel, A. N., Beukema, W., Acevedo, A., Burrowes, P. A., Carvalho, T., Catenazzi, A., De la Riva, I. Fisher, M. C., Flechas, S. V., Foster, C. N., Frías-Álvarez, P., Garner, T. W. J., Gratwicke, B. Guayasamin, J. M., Hirschfeld, M. … & Canessa, S. (2019). Amphibian fungal panzootic causes catastrophic and ongoing loss of biodiversity. Science, 363(6434), 1459–1463.

Sigafus, B. H., Schwalbe, C. R., Hossack, B. R., & Muths, E. (2014). Prevalence of the amphibian chytrid fungus (Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis) at Buenos Aires National Wildlife Refuge, Arizona, USA. Herpetological Reviews, 45, 41–42.

Sherwood, A. M., Claveau, R., Lancelotta, R., Kaylo, K. W., & Lenoch, K. (2020). Synthesis and characterization of 5-MeO-DMT succinate for clinical use. ACS Omega, 5(49), 32067–32075.

Uthaug, M. V., Lancelotta, R., Szabo, A., Davis, A. K., Riba, J., & Ramaekers, J. G. (2020). Prospective examination of synthetic 5-methoxy-N, N-dimethyltryptamine inhalation: Effects on salivary IL-6, cortisol levels, affect, and non-judgment. Psychopharmacology, 237(3), 773–785. doi: 10.1007/s00213-019-05414-w.

Uthaug, M. V., Lancelotta, R., van Oorsouw, K., Kuypers, K. P. C., Mason, N., Rak, J., Šuláková, A., Jurok, R., Maryška, M., Kuchař, M., Páleníček, T., Riba, J., & Ramaekers, J. G. (2019). A single inhalation of vapor from dried toad secretion containing 5-methoxy-N, N-dimethyltryptamine (5-MeO-DMT) in a naturalistic setting is related to sustained enhancement of satisfaction with life, mindfulness-related capacities, and a decrement of psychopathological symptoms. Psychopharmacology, 236(9), 2653–2666. doi: 10.1007/s00213-019-05236-w.

Walls, S. C., & Gabor, C. R. (2019). Integrating behavior and physiology into strategies for amphibian conservation. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, 7, 234. https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2019.00234

Take a minute to browse our stock:

Did you enjoy reading this article?

Please support Chacruna's work by donating to us. We are an independent organization and we offer free education and advocacy for psychedelic plant medicines. We are a team of dedicated volunteers!

Can you help Chacruna advance cultural understanding around these substances?