Although interest in psychedelics has grown exponentially in the twenty-first century, it has largely been based on ethnocentric notions of healing the individual through a psychotherapeutic approach that has been proving to be rather limited (Brennan, 2020). Very little attention has been directed towards engagement with these medicines that involves dancing as collective, participatory psychedelic practice. Both Santo Daime and raving grew out of grassroots movements resulting from hybridization of cultures in times of great change and, although they might not appear to have much in common beyond use of psychoactive substances, the fact that they are both also centered around dancing can shed light on effective corporeal practices that have implications not only for individual healing, but within the larger fight for social and environmental justice.

The corporeality of moving bodies is not only central to their healing potential, but an important form of counter-hegemonic resistance that ought not be overlooked as we face multiple, intersecting planetary crises and make claims that psychedelics may be part of the solution.

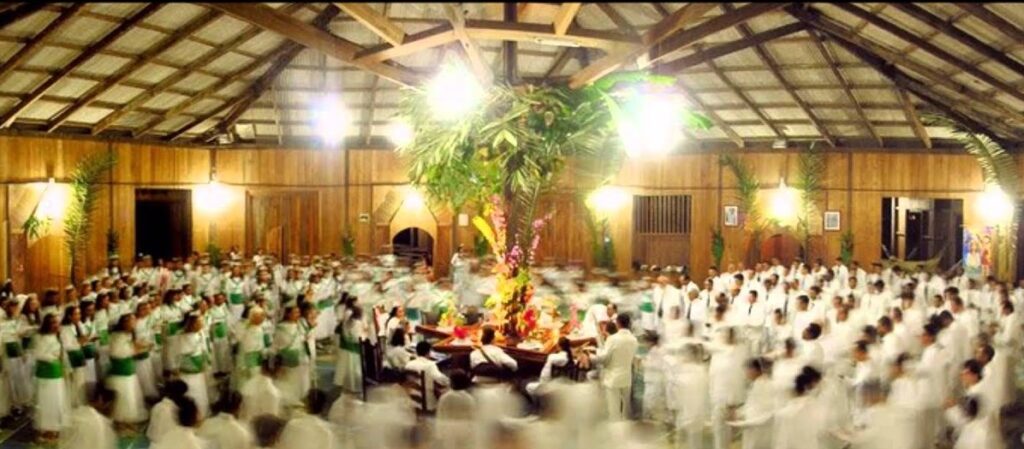

Santo Daime is a Brazilian ayahuasca religion from the southern Amazon, founded in the 1930s, in which participants pray, sing hymns, and dance together around a central altar. Raves—dance parties featuring performances by DJs at which psychedelics are ingested, often taking place in remote, hard to find places—came into being in the late 1980s in Britain (Gauthier, 2004). Both of these practices usher in profound experiences through which many people come to make significant lifestyle changes centered around the practices themselves. The corporeality of moving bodies is not only central to their healing potential, but an important form of counter-hegemonic resistance that ought not be overlooked as we face multiple, intersecting planetary crises and make claims that psychedelics may be part of the solution.

The Body

In his book on raving as a religious practice, Robyn Sylvan claims that the emphasis of “being in the body” cultivated in raves is in sharp contrast to Western civilization’s Cartesian maxim of “I think, therefore, I am,” which has led to a primary focus on the mind as one’s true identity and a culture-wide sense of disembodiment (Sylvan, 2005). Sylvan quotes ravers’ accounts of their experiences in which they claim that dancing is the primary activity that opens the doorway to powerful, healing states. They reflect that it feels like being in your body and out of your head, feeling every aspect of your body, feeling that consciousness rests within physical matter, and that there’s no separation. Graham St. John likewise describes a materialized, felt collectivity in the rave experience as a unified mass, swayed by musical manipulations and enhanced by “dance drugs” (St. John, 2004).

Many describe an effortlessness or being moved by the music while raving, that the music or beats simply move through them (Sylvan, 2005). While this may also be said for experiences at music festivals like Lollapalooza and Rock in Rio, Sylvan and others make the argument that raves, often unauthorized events, are a legitimate religion. St. John refers to rave culture as an embodied practice comparable with world entheogenic rituals, and a heterogeneous global phenomenon, motivating new spiritualities and indicating the persistence of religiosity among contemporary youth (St. John, 2004). The operative word here is “embodied,” a quality that the Santo Daime bailado shares with raving as a religious practice.

The Santo Daime “bailado” is a danced work in which participants drink daime, also known as ayahuasca, and dance and sing together around a common center for many hours. Unlike in raves, where the dance is improvised and people can move around in the space at will, the bailado consists primarily of three dances: the march, the waltz and the mazurka, and each participant has a designated space within the group formation. From a religious studies perspective, the use of psychedelic substances in practices such as raving and the Santo Daime bailado suggests a return to numinous experiences like the ones shared by the ravers in Sylvan’s ethnography. The embodied quality of both these religious dance practices is critical for cultural survival and the fight against erasure as a form of knowledge production and transmission. As Diana Taylor points out, if performance (including religious performance) did not transmit knowledge, only the literate and powerful could claim social memory and identity (Taylor, 2003).

Moving Bodies

In the Santo Daime bailado, “works” (as in “spiritualwork,”) dancing is central (Assis, 2020). Santo Daime founder, Raimundo Irineu Serra, known as Mestre (Master) Irineu, integrated dancing into the works within the first years of the practice. Having migrated to the Amazonian state of Acre as a young man after growing up in Maranhão, the young Irineu Serra is believed to have been drawn to the Afro-Brazilian practices popular in his home state, such as Tambor de Crioula and Bumba Meu Boi, both of which involve dancing (Macrae & Moreira, 2011). Many Indigenous groups from northern Brazil who work with plant medicines that contain DMT also dance and sing together while under the medicine’s force. Regardless of how the inspiration came to him, when Mestre Irineu gave his companions in Acre instructions to dance the Santo Daime bailado, he was rebirthing the timeless and important practice of moving our bodies together in unison.

There is more emphasis on the body in relation to sickness and suffering through ingestion of psychedelic medicines than on wellness and pleasure, and many are fearful of losing control of their body by purging, falling down, or worse.

Movement, or what Maxine Sheets-Johnstone terms “self-movement,” is the origin of all knowing and the generative source of our sense of aliveness (Sheets-Johnstone, 1999). Stillness as a practice has its value, for sure, but there seems to be an overemphasis on stillness when it comes to Western clinical psychedelic use, as if any movement of the body might interfere with the effects of the medicine. There is more emphasis on the body in relation to sickness and suffering through ingestion of psychedelic medicines than on wellness and pleasure, and many are fearful of losing control of their body by purging, falling down, or worse. Much less attention is focused on the body as a source of joy, agency and wisdom through psychedelic practices that involve self-movement in the form of dance.

The simple, rocking movements which make up the Santo Daime bailado recall forces of nature, such as the rolling of ocean waves and the swaying of trees in the wind. Performed synchronously and collectively, individual moving bodies become part of a larger, moving current in which participants can feel their place and their belonging while performing the bailado. Oneness is also emphasized by many ravers who experience a mystical union on physical, somatic, and kinesthetic levels, achieved through complete improvisation and liberating individual expression within the collective vibe created on a dance floor (Sylvan, 2005). Through an unlikely comparison between the Santo Daime bailado and the rave, the universal centrality of the moving body comes into focus, allowing for alternative subjectivities of the racialized and gendered body that are both introspectively and expansively agentic when defined by self-movement.

Through an unlikely comparison between the Santo Daime bailado and the rave, the universal centrality of the moving body comes into focus, allowing for alternative subjectivities of the racialized and gendered body that are both introspectively and expansively agentic when defined by self-movement

Histories

Raves were born in the late 1980s when Londoners vacationing in Ibiza brought the practice back with them and started hosting parties that combined the availability of MDMA—distributed in large quantities under the name “ecstasy”—and house music, influenced by the disco era that ushered in the new notoriety of DJs. Practitioners were privileged young party goers looking for an escape from the meaninglessness of Thatcher/Reagan era economics. Over the years, Sylvan explains, raves developed a sense of religiosity and, as they moved to the US and especially to California, they incorporated spiritual imagery borrowed from Native American traditions, Hinduism, and Buddhism, and a wide range of other therapies and philosophies as practices became more ritualized (Sylvan, 2005).

Though the conditions out of which the psychedelic practices of Santo Daime and raving emerged are quite different, even at opposite ends of the social spectrum, they both bloomed from the need for alternatives to the disempowering and isolating subjectivity of global capitalist markets.

Santo Daime came into being as the young nation of Brazil was busy denying its racist foundation in slavery, which had only officially been abolished in 1888, when a new constitution was written. Mestre Irineu had migrated from the impoverished Northeast of Brazil to the Amazon Basin seeking work generated through the rubber boom, as had many of his companions, the majority of whom were poor, Black and lacked literary skills (Macrae & Moreira, 2011). Though the conditions out of which the psychedelic practices of Santo Daime and raving emerged are quite different, even at opposite ends of the social spectrum, they both bloomed from the need for alternatives to the disempowering and isolating subjectivity of global capitalist markets. This suggests that they may carry seeds of social mobilization that could germinate within the newly sprouting psychedelics movement as it becomes aware of its own neocolonial tendencies, and the winds that scatter these seeds may be the practice of collective self-movement, or dance.

Justice Against Epistemicide

As we know by now, the set and setting that psychedelic medicines are ingested in has much to do with determining the results achieved through engagement with them (Hartogsohn, 2020). So, why do most Western approaches to working with psychedelics involve so much physical stillness? Boaventura de Sousa Santos describes the Renaissance period as a time when the elite sought repose and permanence, reflected in the ideology and aesthetics that came to define the period (Santos, 2014). It is no mistake that recent interest in psychedelics is being dubbed the “Psychedelic Renaissance,” as millions of dollars pour into clinical research that could lead to pharmaceutical patents, just as capital investment in overseas ventures dominated the sixteenth and seventeenth century Renaissance period. As we witness a widening gap between the rich and the poor, will psychedelics become just another commodity privatized by the one percent? The less we move and the more we sit still or lie down, the more likely this is to happen.

If psychedelics have potential to heal, enlighten, and empower us, what good is this light and this power if it doesn’t move?

Santos encourages us to fight for justice against “epistemicide”: the annihilation of forms of knowledge by neoliberal capitalist regimes that privilege cognitive science. He claims that we began the twentieth century with Marx and Freud’s socialist, introspective revolutions, but that we are starting the twenty-first century with the body revolution, with corporeality replacing class and psyche as the root of all options (Santos, 2014). I would add to this that the new revolution, if we are truly to honor the pluriverse and its wealth of knowledge, will be realized through movingbodies, bodies that move together, and that psychedelics can serve as a catalyst to this movement, but cannot replace the movement itself. If psychedelics have potential to heal, enlighten, and empower us, what good is this light and this power if it doesn’t move? In the Santo Daime bailado and, more recently, in raving, we have important examples of the role movement can play not only in healing the individual, but in bringing people together on a regular basis over time with the shared desire for a better, more harmonious world.

Art by Karina Alvarez

References

Assis, G. L. de. (2020, August 13). Mestre Irineu: A black man who changed the history of ayahuasca. Chacruna. https://chacruna.net/mestre-irineu-ayahuasca/

Brennan, B. (2020, July 3). The revolution will not be psychologized: Psychedelics’ potential for systemic change. Chacruna. https://chacruna.net/the-revolution-will-not-be-psychologized-psychedelics-potential-for-systemic-change/

Gauthier, F. (2004). Rave and religion? A contemporary youth phenomenon as seen through the eyes of religious studies. Studies in Religion/Sciences Religieuses, 33(3–4), 397–413.

Hartogsohn, I. (2020, July 30). How set and setting shape psychedelic cultures. Chacruna. https://chacruna.net/set-setting-shape-psychedelic-cultures/

Macrae, E., & Moreira, P. (2011). Eu venho de longe: Mestre Irineu e seus companheiros [I come from afar: Master Irineu and his companions]. Salvador, Brazil: SciELO Books – EDUFBA. https://www.doabooks.org/doab?func=search&query=rid:22569

Santos, B. de S. (2014). Epistemologies of the South: Justice against epistemicide. Boulder, CO: Paradigm Publishers.

Sheets-Johnstone, M. (1999). The primacy of movement. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: John Benjamins Pub.

St. John, G. (Ed.). (2004). Rave culture and religion. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

Sylvan, R. (2005). Trance formation: The spiritual and religious dimensions of global rave culture. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

Taylor, D. (2003). The archive and the repertoire: Performing cultural memory in the Americas. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Take a minute to browse our stock:

Did you enjoy reading this article?

Please support Chacruna's work by donating to us. We are an independent organization and we offer free education and advocacy for psychedelic plant medicines. We are a team of dedicated volunteers!

Can you help Chacruna advance cultural understanding around these substances?