Conflict of interest disclosure: The author is the executive director of Vital Oregon LLC, a Psychedelics Today company that intends to provide training to people who seek facilitators’ licenses under Oregon’s Measure 109 program. The author also intends to participate in the opening of a community-based psilocybin service center cooperative under the Measure. The author is a member of the Psychedelic Bar Association Religious Use Committee and is a founding member of the Entheogenic Practitioners Council of Oregon, both of which are mentioned in this article.

Introduction

The “community practitioner framework” is a model regulatory framework for affordable, community access to psilocybin services and products under Oregon’s psilocybin program, known as Measure 109 (M109). The framework is an attempt at helping Oregon meet its statutory mission of ensuring that psilocybin becomes “a safe, accessible and affordable therapeutic option for all persons 21 years of age and older in this state for whom psilocybin may be appropriate[,]” including the 520,000 Oregonians living in poverty and the 210,000 living in deep poverty. ORS 475A.205(1)(c). The framework promotes affordability within the M109 system by allowing responsible communities to utilize safeguards that are proportionate to the safety risks of a particular administration session in light of the idiosyncratic factors of that session.

1. History of the Community Practitioner Framework

Originally conceived of as primarily a religious freedom initiative, called the “entheogenic practitioner framework,” the framework was drafted in an attempt to create affordable pathways for services and to bring the M109 program into alignment with the religious liberties that are already recognized by the federal government through the Religious Freedom Restoration Act. The framework has evolved in response to stakeholder input into a religiously-neutral community model that allows responsible adults to utilize certain “privileges” when products and services are provided in the context of responsible community use.

The entheogenic practitioner framework was originally presented to the Oregon Psilocybin Advisory Board (OPAB) Licensing Subcommittee on February 3, 2022. At its next and final meeting on March 3, the Licensing Subcommittee voted 4-1 to recommend that the framework be adopted along with a special manufacturing endorsement for entheogenic use. The entheogenic practitioner framework was also considered during the March 2, 2022 meeting of the OPAB Equity Subcommittee. During the Equity Subcommittee’s next meeting on March 18, the Subcommittee voted 11-0 to endorse the entheogenic practitioner framework and to create a new “Entheogenic Practice Subcommittee” of OPAB.

Then, between April 1-22, the Oregon Health Authority (OHA) began a public comment period for the regulations concerning psilocybin products, products testing, and facilitator training programs. OHA received widespread and enthusiastic public comment in support of the entheogenic practitioner framework.

During public hearings held on April 18, 2022 and April 22, 2022, public comment was overwhelmingly in favor of the framework, with an estimated 75% of all commenters voicing support for equity, affordability, religious freedom, a community-based services model, and/or sensitivity to Indigenous-use and cultural appropriation issues.

Additionally, the entheogenic practitioner framework received significant support in the written comments that were submitted. Written comment was received from:

- David Bronner, the single largest donor to the Measure 109 campaign;

- Dr. Bill Richards, a clinical researcher Johns Hopkins researcher and author of Sacred Knowledge (you can read his comment reprinted in this article);

- The Psychedelics Bar Association’s Religious Use Committee;

- The Entheogenic Practitioners Council of Oregon (EPCO).

EPCO also circulated a petition calling on OHA to adopt the entheogenic practitioner framework, which received over 500 signatures.

OHA’s response to the public comments around the framework was contained in a May 20 letter:

Many members of the public expressed support for an “Entheogenic Framework” for licensing. This framework refers to a document that that has been presented to Oregon Psilocybin Advisory Board subcommittees and proposes an alternative set of requirements for licensees who qualify as entheogenic practitioners. Because the framework proposes exceptions to rules that have not yet been drafted, and because the Oregon Psilocybin Advisory Board has yet to consider the proposal, OPS did not address these comments in the current rulemaking. OPS is committed to understanding the impact of statute and rules on entheogenic practices through collaboration and partnerships with communities.

Five days later, on May 25, the full OPAB finally had occasion to take up the entheogenic practitioner framework. Before considering the framework, OPAB went into executive session for the first time in its 14-month history. When the board emerged from the session, the motion to recommend the framework failed by a 10-3 vote.

During the same May 25 meeting, OHA announced the release of a curiously-timed legal memorandum by the Oregon Department of Justice (ODOJ) about the framework. The memo opined that the entheogenic practitioner framework raises the Establishment Clause concerns because it offered privileges exclusively to certain religious license holders. The memo appeared to be the primary basis upon which the framework was rejected by the board. However, the ODOJ memorandum has been criticized as being based on a misunderstanding of the framework. Marijuana Moment, Benzinga, and others have also reported on the vote and concerns related to the vote.

2. The ODOJ Memo

The ODOJ Memo found the entheogenic practitioner framework to be problematic on the basis that:

“Making less restrictive standards for entheogenic practitioners would likely violate the establishment clause protections of the Oregon and United States constitution. Applying fewer restrictions on entheogenic practitioners would likely be viewed as granting a privilege to religion that is not available on a secular basis.”

As noted earlier, this reflects a misunderstanding that the entheogenic practitioner framework offered privileges to religious groups that were not available to secular groups. The initial article describing the framework and the Licensing Subcommittee presentation in which the framework was presented (at 1:21:28) both clearly indicate that even the original entheogenic framework was specifically designed to not give preferences to “religious” over “non-religious” organizations or individuals.

Moreover, as the entheogenic framework evolved into a community model, it lost any reference to religion and any pretense at an Establishment Clause problem, as described in Section 4 of this article.

In short, the concerns raised in the ODOJ memo do not apply with respect to the revised community practitioner framework, and they cannot be a legally valid pretext for disregarding the framework.

3. What are the Highlights of the Framework?

What follows is a summary of the key differences between the community practitioner framework and the general rules that govern the rest of the M109 program.

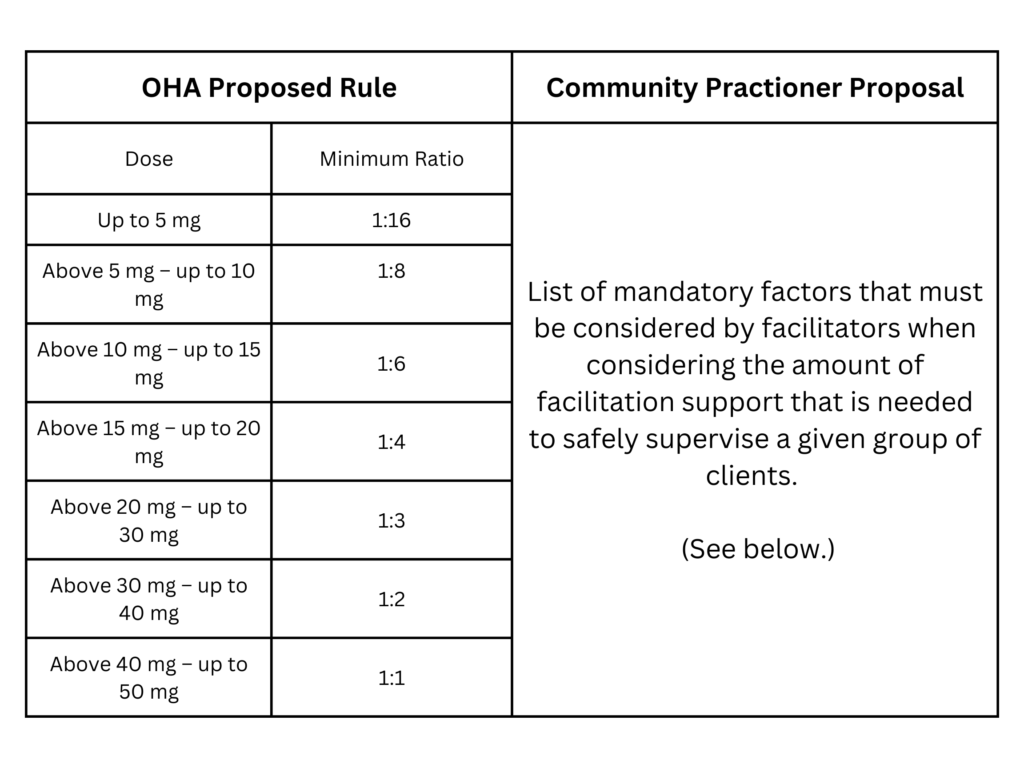

A “facilitator-to-client ratio” is the minimum ratio of facilitators that must supervise a given number of clients during a group administration session. The proposed OHA rule concerning facilitator-to-client ratios has no flexibility to allow experienced, responsible facilitators and experienced, responsible clients to have lower costs administration sessions when less facilitation assistance is needed than the amount required under the draft rules.

These ratios are not a safe-harbor; facilitators will not avoid professional or civil liability if they unreasonably defer to these ratios. Instead, facilitators will already be required to consider a number of factors in determining the amount of facilitation that is actually needed. These factors include:

(a) The types of activities the group intends to engage in;

(b) The relevant experience and skill of the facilitators who are providing supervision;

(c) The facilitator’s familiarity with the clients participating in the session;

(d) The amount of psilocybin being consumed by the clients;

(e) A mental or behavioral health condition of any member that increases the likelihood of requiring support during the session;

(f) The group and its members’ prior experience with psilocybin, other psychedelics, or other non-ordinary states of consciousness,

(g) The clients’ relevant skill or training in psychedelic peer-support;

(h) Any other risk or safety factors known to the facilitator.

Rather than have a rigid, arbitrary upper limit, the community practitioner framework would allow facilitators to consider idiosyncratic factors of a given group, so that the facilitation expenses of a community group administration session are in proportion to the safety needs of that particular group.

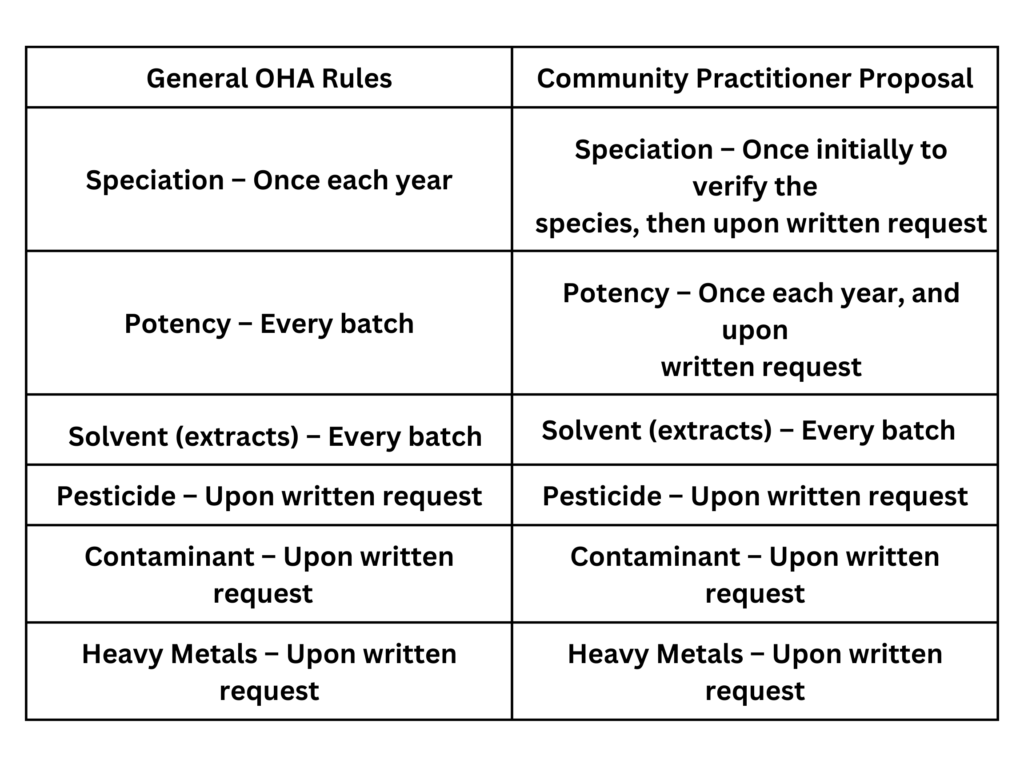

POTENCY TESTING

Summary of OHA testing rule and proposed testing privilege

OHA rules will generally require mandatory potency testing of every batch of mushrooms grown. The currently-available psilocybin testing technology is neither accurate nor precise, largely because of the variability in potency between one mushroom and another within the same batch, and even within different parts of the same mushroom.1 However, mandatory testing of every batch will add substantially to the costs of the mushrooms according to the whims of what is expected to be a small and volatile Oregon testing market. The current unregulated psilocybin market does not typically utilize potency testing, and in the unregulated market dosing is typically decided by the bulk weight of dehydrated mushroom fruiting body. Under the framework, dosing would be determined based on the results from the most recent potency test for a particular psilocybin cultivar, which is a substantial improvement upon the dosing precision that is generally used in the unregulated market.

The two deviations that the community practitioner framework would make from the generally applicable rules do not add substantially to the safety risk of using psilocybin. Less precise dosing has not been the cause of any harms in the unregulated market that the authors of this memorandum are aware of. Additionally, within the M109 system, where all psilocybin is consumed under the guidance and supervision of licensed professional facilitators, the potential risks arising from less precise dosing are even lower still.

(See Section 4 below for a discussion on how OHA’s proposed testing rules likely violate Measure 109.)

MAXIMUM DOSES

The maximum amount of psilocybin that a client may consume under the proposed rules is 50 mg per session. While 50 mg will be a higher dose than most clients will want, there is substantial variability in individuals’ metabolic rates for psilocybin, and 50 mg may not be enough for some people who have high metabolic rates and who come to the M109 program seeking a deep mystical-type experience. This rule would also force all people who wish to have deeper experiences to take psilocybin outside of the safety of the M109 container, which appears likely to have a more harmful impact on public health and safety than allowing them into the M109 program. Additionally, under the federal Religious Freedom Restoration Act, the federal government would not be legally allowed to impose maximum dosing limits on religious practitioners who use psilocybin unless the government could demonstrate that it had a “compelling interest” in limiting the dosing and that such a limitation was the “least restrictive means” of achieving that interest.

RECIPROCAL EXCHANGE PROGRAMS

The community practitioner framework mandates participation in a reciprocal exchange program. The proposed general rules do not require any such participation. Under the framework, a reciprocal exchange program is a program that collaborates with one or more communities that have historically engaged in the use of psilocybin-containing mushrooms or other psychedelic plants or fungi. The goals of the collaboration may include:

(a) Promoting cultural equity, as that term is defined in OAR 333-333-1010(17) in the provision of psilocybin products or psilocybin services in Oregon or elsewhere;

(b) Minimizing or reversing the impacts of colonialism, extraction, or cultural appropriation on a historical plant medicine community, or promoting the self-determination of that community;

(c) Undoing harm caused by the War on Drugs.

This provision aims to keep community practitioners in alignment with the ethical best practices of the psychedelic community, which includes ensuring that use of traditional psychedelic plants and fungi be done in ways that are not extractivist and that reduce or reverse the impacts of colonialism.

The framework mandates that community practitioners submit an annual summary of their reciprocal exchange program participation to OHA, and it would require OHA to publish those reports. This is design to give positive incentives for practitioners who have meaningful participation in a reciprocal exchange program. The framework does not punish people for failing to participate meaningfully.

OTHER PRIVILEGES INCLUDED IN THE DRAFT OHA RULES

The framework includes other privileges not enumerated elsewhere in this memorandum, including: outdoor administration sessions; group administration sessions; the ability for clients to receive multiple preparation and integration sessions; the ability for clients not have to repeat intake, screening, and preparation sessions more frequently than once each year, unless a client’s health or personal circumstances change; and for facilitators to participate in the activities of an administration session, so long as they remain attentive to client needs and do not take psilocybin.

These issues have not been addressed specifically in this memorandum because the OHA draft rules have included them as part of the rules, and additional explanation does not appear to be necessary at this time.

Discover the Indigenous Reciprocity Initiative of the Americas

4. OHA’s Potency Testing Rules Might Violate Measure 109

Additionally, before adopting testing rules, ORS 475A.590(7) requires OHA to consider how the costs of testing rules will affect the costs to the ultimate client. That law also prohibits OHA from adopting testing rules“that are more restrictive than is reasonably necessary to protect public health and safety.” Emphasis added.

If OHA is prohibited from adopting rules that are more onerous or expensive than what is “reasonably necessary to protect public health and safety,” what is necessary to protect public health and safety?

To date, OHA has provided no public information describing what public health or safety risks justify its rules. The rules adopted last May require separate potency tests be administered for each “harvest lot” of mushrooms, which means mushrooms that are “cultivated and dried under the same conditions and harvested within a 24-hour period at the same location within the licensed premises.” OAR 333-333-1010(10). That mushrooms harvested outside of a common 24-hour window must be tested by a different test.

In its “Notice of Proposed Rulemaking” in which these rules were adopted, OHA described the situation as: “the testing rules require psilocybin products to undergo certain tests before they may be sold. Licensed psilocybin manufacturers will pay costs to perform the required tests. A portion of these costs could ultimately be passed onto clients.” Elsewhere in the Notice, OHA acknowledges that “[t]he testing rules are likely to impact lower income clients more acutely * * *.”

To justify the added costs, OHA offers only the following explanation:

“Less restrictive rules could carry a lower cost of compliance for manufacturers. However, this lower cost would be coupled with higher risks of negative outcomes for clients, including health and safety concerns, leading to fiscal and economic impact to individuals. Additionally, an appropriately regulated market creates consumer confidence and encourages members of the public to access psilocybin services through the ORS chapter 475A model rather than purchasing from sources in the unregulated market.”

To emphasize: OHA’s sole justification for requiring that every batch of mushrooms be tested for potency is because of “higher risks of negative outcomes for clients, including health and safety concerns, leading to fiscal and economic impact to individuals.” OHA has never identified any particular risks that justify its testing rules, despite significant public support for less restrictive testing rules. OHA’s actual reason for the rule appears to be to promote “consumer confidence,” which is not a valid legal reason for more restrictive testing rules under ORS 475A.590(7).

In short, mandatory potency testing of every batch of psilocybin mushrooms might violate the M109 requirement that testing rules not be “more restrictive than is reasonably necessary to protect public health and safety.” ORS 475A.590(7).

5. Statutory Rulemaking Authority

Concern has been voiced that, because M109 doesn’t specifically mention “community practitioners,” OHA might not have rulemaking authority to adopt the framework. Administrative rules are invalid when they exceed the scope of an agency’s statutory rulemaking authority. However, administrative agencies can adopt rules where it is carrying out a policy entrusted to it in the authorizing statute. See, e.g., Morgan v. Stimson Lumber Co., 607 P.2d 150 (Or. 1980). (An agency exceeds rulemaking authority when it prohibits the advertising of pharmaceutical drugs and where the authorizing statute neither gives express authority for such a rule nor states a policy which is furthered by the challenged rule.)

Oregon courts have reviewed cases in which it is alleged that an agency exceeded its rulemaking authority despite there being a “catch all” rulemaking provision where the agency is delegated maximum permissible rulemaking authority by the enacting statute. In Van Ripper v. Liquor Control Commission, 228 Or 581, the statute in question gave the OLCC rulemaking authority that included “the powers and duties specified in this chapter, and also the powers necessary or property to enable it to carry out fully and effectually all the purposes of this chapter.” In this case, OLCC enacted a rule requiring strip clubs to have at least 25% of gross receipts from all food and liquor sales to come from food, even though no such food-liquor distinction could be found in the rulemaking authority statute. The court found that the regulation was validly adopted because it furthered the statutory purpose of the statute being enacted and because of the “comprehensive character” of the rulemaking authority in the statute. Id., at 590.

M109 delegates similarly comprehensive rulemaking authority for OHA to “adopt, amend or repeal rules as necessary to carry out the intent and provisions of ORS 475A.210 to 475A.722, including rules that the authority considers necessary to protect public health and safety[,]” as well as the authority to regulate psilocybin products and psilocybin services “for other purposes as deemed necessary or appropriate by the authority.” ORS 475A.235(2)(b)(C)-(c). In short, this appears to be the widest possible delegation of rulemaking authority that could be given.

Additionally, the express purposes of M109 include: “[t]o develop a long-term strategic plan for ensuring that psilocybin services will become and remain a safe, accessible and affordable therapeutic option for all persons 21 years of age and older in this state for whom psilocybin may be appropriate.” ORS 475A.205(1)(c). Moreover, OPAB is also charged with a statutory duty to develop a plan to make services affordable to all people in Oregon. ORS 475A.230(9).

In short, there is clear statutory rulemaking authority for OHA to adopt rules that promote affordable pathways of access because ensuring that psilocybin products and services are affordable “to all persons * * * in this state * * *” is an explicit purpose of the M109 law.

6. Conclusion

There has been widespread and passionate public support for the community practitioner framework and it’s “entheogenic practitioner” predecessor. The legal reasons offered by ODOJ for rejecting the entheogenic practitioner framework do not reflect on the legality of the community practitioner framework and cannot be used as an honest justification for OHA to ignore the opportunities to create a more affordable and culturally-inclusive psilocybin program. Adoption of the community practitioner framework is legally viable and would help achieve OHA’s goal of ensuring psilocybin becomes “a safe, accessible and affordable therapeutic option for all persons 21 years of age and older in this state for whom psilocybin may be appropriate.” ORS 475A.205(1)(c).

A copy of the framework may be found here.

Julian Kanter contributed to this article.

Art by Trey Brasher.

Notes

1 See, e.g., Morphological and chemical analysis of magic mushrooms in Japan Forensic Science International, Volume 138, Issues 1–3, 17 December 2003, Pages 85-90, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0379073803003785.

Take a minute to browse our stock:

Did you enjoy reading this article?

Please support Chacruna's work by donating to us. We are an independent organization and we offer free education and advocacy for psychedelic plant medicines. We are a team of dedicated volunteers!

Can you help Chacruna advance cultural understanding around these substances?