- The Greater Mysteries of Plant Music - December 23, 2019

- Sonic Journeys: An Interview with Byron Metcalf - September 25, 2019

- High Holy Strangeness: A Playlist for Ketamine by Eric Sienknecht - March 20, 2019

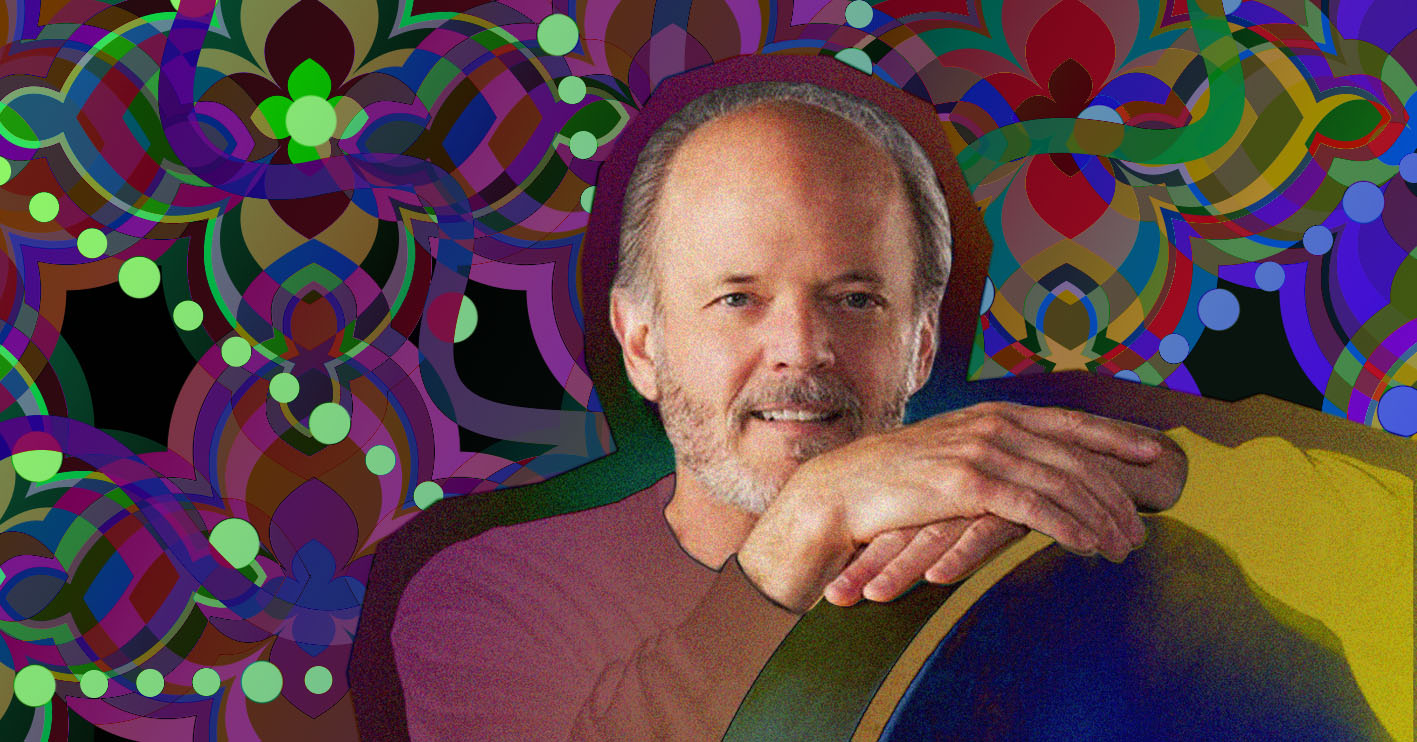

Byron Metcalf, PhD, is a therapist, explorer of consciousness, and musician who specializes in creating music for neoshamanic work. He began his career playing drums with country music legends Waylon Jennings and Kenny Rogers before creating his own style of deep, long-form music for inner journeys. Over the years, he has collaborated with Steve Roach, Mark Seelig, Sandra Ingerman, and many others. Byron has released over 20 albums and created his own style of musically-driven shamanic psychotherapy, called Holoshamanic Strategies. He created a playlist of his music to share with Chacruna and talks with us here about his decades of experience using music to support non-ordinary states of consciousness.

R: What are you best known for?

BM: I’m mostly known for my music. People are kind of surprised when they discover I’ve been a psychotherapist of over 30 years. But I got started in music, playing professionally when I was 15.

R: How did you get such an early start as a professional musician?

BM: I saw The Gene Krupa Story and became obsessed with drumming. My father bought me an old beat up set of drums and nine months later I’m playing in little bars and clubs in Phoenix and it just went from there; a lot of lucky breaks and synchronicities. I went to Nashville at the right time and ended up hooking up with a big country singer, Dottie West, who I eventually married. I played on Waylon Jennings’ first album on A&M when I was 16 years old; also, on Kenny Rogers’ The Gambler album.

R: So, how did you get into these more expansive musics? Was it a spiritual opening that happened and then the music came through? Or was it a musical opening and the spiritual came through?

BM: Kind of both. I got out of the music business during a kind of mid-life correction. I became involved in holotropic training, so I had an early introduction and grounding with Grof’s transpersonal model, and I also started training with shamanic practitioners. I rented some recording equipment from a friend and recorded this kind of raw and tribal album. But you know, it was released in 1998 and it still sells.

R: When you trained in holotropic breathwork, did they offer the music module at that time?

BM: At that time, it wasn’t a discrete module per se, but they were always talking about the music during the training. When Christina Grof was there, I liked some of the music she brought to it, but she did have a strong bias toward classical music.

R: So, with your emphasis on more flowing types of tribal music, did that feed back into and influence how the Grofs worked with music?

BM: Perhaps, but every practitioner has their own style. There are some people now who put together music sessions with lots of dub and electronic dance music that feel monotonous as hell to me. I don’t respond to it at all.

R: Something I noticed when I did holotropic breathwork was that the music in our session had intense low-end frequencies, bassy drums, and deep drones.

BM: That level of low-end energy can be really effective. I remember we did several workshops at Joshua Tree where Brugh Joy’s old system was set up that had this wall of 18-inch subwoofers; the low end was just huge! My preference, though, is not to do that because too much low end is going to smear the detail, especially in the midrange where most of the sonic information is. I want clarity across the entire spectrum and that’s partly why people respond to my mixing; it’s clear and pristine.

R: What do you think of Helen Bonny’s work?

BM: She was the one who was doing the music at Spring Grove with Grof’s LSD research. As I studied her work, her bias became apparent. Everybody has biases, but I think you need to own them. To me, Helen came across as, “this is the only thing that’s valid.” That assumption is simply incorrect. We know that the music you love the most can have a healing effect.

R: So, Helen Bonny privileged Western classical music?

BM: Oh absolutely. But I rarely use classical music in sessions. Sometimes only a track or two. But it works great for some people.

R: Helen Bonny was the first to break the session into different phases with specific music for each phase. What do you think of this model?

BM: In the trajectory of a holotropic breathwork session, they refer to the phases as hour one, hour two, and hour three. Obviously, the choices of music are going to be different for psychedelic work, and you don’t need a lot of driving drums and intensely dynamic music because the medicine is doing it. They may be helpful but you have to be cautious about how much of it you use and how aggressive it is. Most importantly, there has to be an element of heart in all of the music. If that intention and understanding is there, it will be infused into the playlist and it’s going to come through for the journeyer.

R: How does your personal experience of psychedelic work inform the music that you make?

BM: It’s been 15 years since my last ayahuasca session but it still very much informs the music. Not so much when I’m playing, but when I’m mixing. That’s when the sonic landscape is being created. It’s kind of like ancestral memories, and at that point I just trust it implicitly. Also, my direct experience of certain pieces of music or certain aspects of a piece of music in rituals or sessions would inform me deeply, as much as a teacher would. With MDMA, specifically, there’s a capacity to really inquire and reference into the music that’s helped me in creating music. Later, when I’m in the studio, I’ll see if I can capture what that was.

R: Do you ever hear from people who have used your music in psychedelic sessions?

BM: I get reports almost daily. A lot of the music is now scored for psychedelic work, like the project I just released with Mark Seelig, Persistent Visions. This is a quintessential MDMA album. We composed and constructed it with that in mind and, of course, it is infused with that intention. Now, it’s only 70 minutes long, but any piece of it is going to work. You can open with it, close with it, or use it in the middle.

R: Tell me about Holoshamanic Strategies. What role does music play in that work?

BM: Well, obviously, it’s a big one. When I’m working with individual clients I use a lot of different music. And there will be periods where it can look like talk therapy but we’re working at very deep levels. So, to incorporate the music, I mix different tracks and also play live with pre-recorded tracks. I’ve got an array of all these instruments: bowls, bells, rattles, drums, and sometimes I use voice or toning.

R: On the Holoshamanic Strategies site, I saw references to something called “Field Effect Audio Technology.” What is that?

BM: It’s my brain entrainment technology that can quickly shift you into a theta brainwave state. It took about three years to create my own application, which incorporates both binaural and isochronic beats, which are more time-aligned and work great with the rhythmic compositions that I do. These are amazing tools for exploring consciousness and, if you put on the headphones and do it like it’s suggested, the brain is going to entrain; it can’t help but do so.

R: Have you heard of anyone using binaural beats for psychedelic work?

BM: I know that people have tried it and there is some research interest in exploring it, but honestly, for psychedelics, I think it’s totally unnecessary. But there’s an interesting research question: Would binaural beats work for someone who doesn’t respond well to psychedelics? I know of cases where breathwork has led to breakthroughs where psychedelics had failed.

R: How many times did you do live music for Grof?

BM: I did it three times for the Insight & Opening retreats in Joshua Tree with Stan Grof and Jack Kornfield, combining holotropic breathing with vipassana meditation. It was a real thrill for me, and Stan said that this format was his favorite way to present breathwork.

R: Terrence McKenna wrote about taking five grams of mushrooms in silence and darkness. Do you have experience with any kind of psychedelic work that does not involve music?

BM: No. I know some people who will experiment with just having silence, and I think it’s important to have periods of silence. I probably experienced silence most profoundly myself with ayahuasca—this pregnant silence—in a way that was so potent and large. But doing a whole session in the dark, with silence, does not really appeal to me.

R: How do you think the sound quality of music production supports and affects psychedelic work?

BM: Well, that’s really subjective. Because when synesthesia is happening, who knows what’s going on with the music? I’ve participated in sessions using a funky boom box that sounded amazing. But my ears are trained to such sonic integrity and balance that sound quality is of paramount importance to me.

R: Tell me about your collaborations with one of my favorite musicians, Steve Roach.

BM: I’d been a fan of his because his music was used in the early days of breathwork and his album, Dreamtime Return, was responsible for a huge breakthrough I had in my first guided psilocybin mushroom experience. After my first album came out, we met and I got to see his studio, The Time Room, which was mind blowing. At the time, I was getting ready to do a part of my Ph.D. research on breathwork and I wanted to arrange participants in a circle like an ayahuasca ceremony with shamanic music. So, I was telling Steve about it and he offered to come play live with me. The following day, we also did an invitation-only living room concert to make it worth Steve’s time, and it was incredible! We had the windows blacked out and candles, and he asked me to play some shamanic percussion. It was an amazing experience. When people were walking out of there, they looked like they were on 300 mics of LSD; their eyes were spinning. It went so well, Steve said, “we need to do a collaboration.” And it just evolved over time. Steve is a wizard and his music is so deep. In any of his albums there is the superficial layer, and then layers, and layers of other things that are going on. And if you are able to hear it, then it’s just amazing. We’re going to do a workshop called The Music Is The Medicine in Memphis this October and will be taking people on some live sonic journeys.

You can find a three hour primer of Byron’s music here.

Join us at the Psychedelic Liberty Summit

Take a minute to browse our stock:

Did you enjoy reading this article?

Please support Chacruna's work by donating to us. We are an independent organization and we offer free education and advocacy for psychedelic plant medicines. We are a team of dedicated volunteers!

Can you help Chacruna advance cultural understanding around these substances?