- Introduction to Women and Psychedelics - July 26, 2024

- Global History of Psychedelics: A Chacruna Series - October 4, 2023

- Can Psychedelics Promote Social Justice and Change the World? - August 30, 2021

- Introduction to Women and Psychedelics - July 26, 2024

- A Bridge Between Two Worlds: Ayahuasca and Intercultural Medicine – Interview with Anja Loizaga-Velder - May 18, 2022

- “It is not an orthodox psychotherapy”: An Interview with Ivonne Roquet, Daughter of a Psychedelic Pioneer in Mexico - February 22, 2022

- Introduction to Women and Psychedelics - July 26, 2024

- Mescaline Scribe - February 10, 2021

- Introduction to Women and Psychedelics - July 26, 2024

- Rethinking Power, Plants, and the Future of Psychedelic Culture - May 9, 2025

- Where Is the Psychedelic Movement Headed Next? - October 15, 2024

- The FDA’s Rejection on MDMA-Assisted Therapy: What is Next for the Psychedelic Movement? - August 16, 2024

- Queering Psychedelics: An Introduction - August 7, 2024

- Introduction to Women and Psychedelics - July 26, 2024

- Eight Frequently Asked Questions About Ayahuasca Globalization - February 13, 2024

- Introduction to Women and Psychedelics - July 26, 2024

- Eight Frequently Asked Questions About Ayahuasca Globalization - February 13, 2024

- Ten Tips for Standing in Solidarity with Indigenous People and Plant Medicines - January 18, 2024

Did you know that Susi Ramstein, Albert Hofmann’s lab assistant, was the first woman in the world to take LSD?

Many people may know that R. Gordon Wasson visited María Sabina in Mexico where he learned about the magic of psilocybin mushrooms, but did you know that his wife, Valentina Pavlova Wasson, had a PhD in ethnomycology and wrote a definitive study of mushrooms in Russia? Psychedelics have attracted people from around the globe to studies of consciousness and brain sciences, but did you know that in the 1950s some psychedelic psychiatrists sought guidance from renowned psychic Eileen Garrett to help make sense of the revelatory powers of these drugs? In the case of Latin America, women have also played important roles throughout history, some names can be very well known among the psychedelic community (like the case of famous Maza tec curandera Maria Sabina) but have you ever heard about Madrinha Rita Gregório de Melo? She is a matriarch of Santo Daime religion in Brazil, currently 97 years old. Or did you know that the most famous heroin dealer for the first half of the 20th century in Mexico City was actually a woman named Lola “La Chata”? Lola’s fame was such that the police called her the “empress of drugs”, even William Burroughs would say that she was an “Aztec goddess”. Lola became Mexico’s public enemy No. 1 and a sort of Robin Hood-like character.

Psychedelics are enjoying a rebirth in the 21st century as people recognize their capacity to change the way we think. In this book we encourage readers to also adjust our thinking on the place of women in this psychedelic past as we chart a psychedelic future. The history of psychedelics has often emphasized the contributions made by leading researchers, breakthrough therapists, and champions of a psychedelic ethos. It just so happens that most of the figures whose names were on the scientific papers or political placards were men. But behind the scenes, and even in the same rooms, women and junior colleagues were working toward a psychedelic future. Whether nurses, therapists, healers, interns, wives, or subjects themselves, women’s perspectives on the history of psychedelics help us to highlight a more inclusive past and perhaps a more diverse set of priorities when it comes to thinking about the place of psychedelics in the 21st century.

Whether nurses, therapists, healers, interns, wives, or subjects themselves, women’s perspectives on the history of psychedelics help us to highlight a more inclusive past and perhaps a more diverse set of priorities when it comes to thinking about the place of psychedelics in the 21st century.

There has been a tendency with psychedelic histories to emphasize the colorful, albeit exciting, developments that took place in the United States and ricocheted throughout the Anglo world. Widening the frame to include women in that history at times means looking to some of the wives— whether Humphry Osmond’s wife Jane, Aldous Huxley’s wives Maria and then Laura, or Tim Leary’s wife Rosemary (among others)—whose lives were also deeply affected by their husbands’ fame. But here we also wanted to widen the geographical and linguistic context, to place psychedelics in a longer legacy of networks that move north and south, involving Indigenous women from Spanish and Portuguese communities in Latin America, and across the Atlantic to non-Anglo regions where women participated in shaping how we have come to know psychedelics. French scholar Zoë Dubus shows us how European networks of women significantly influenced how we think about set and setting. Osiris González Romero helps us to better appreciate how María Sabina became a complicated hero—a conduit for bringing mushrooms to the United States, but perhaps a traitor to her own community. Patrick Farrell shows us that while Simone de Beauvoir is famous in her own right as a French philosopher, her intimate relationship with Jean-Paul Sartre meant that she was his trusted scribe on his mescaline journey. By working with Spanish, Portuguese, French, and English authors, our collection crosses many boundaries, urging readers to reconsider some of the standard narratives in this past and to broaden their horizons when thinking about new sources of inspiration in a psychedelic future.

Shop our Collection of Psychedelic T-Shirts.

In this book you will read about some of the diverse and impressive contributions that women have made to our understanding of psychedelics. This is not just a story of psychedelic research and scientific progress; some of these stories serve also as reminders that these substances have a longer history and set of traditions that have at times been carefully hidden from view. Some of that history is a product of blatant sexism, which has resulted in women simply being forgotten, erased, or never fully credited for their contributions in the past. Women got married and changed their names, ended their careers, or never received credit for an idea that went to a husband or colleague whose professional careers seemingly had more at stake. But of course, this was not always the case. For some women, their names are firmly connected with psychedelic history, and were it not for them, we might not be able to piece together some of these stories. Laura Huxley was a keen collector and writer herself. Betsy Gordon established an archive so that we today can review psychedelic triumphs and failures from the past, and hopefully learn from those who came before us. Nina Graboi, likewise collected her own theories and ideas, and later ensured they made their way to the New York Library, offering a vital and different perspective on a burgeoning psychedelic scene in Manhattan.

Beyond pioneering women, our authors also remind us that sometimes women faced barriers and challenges that complicated their roles in this past. Women’s roles intersected with other isms—race, place, language, age, and career, to name a few. Women engaged in botanical stewardship did not always fare well in a global effort to exploit resources from the earth, especially when psychedelic plants were not considered to be of value in an industrial commercial venture. Despite colonial pressures to undermine Indigenous knowledge, plant medicines, and women’s healing techniques, our authors find spaces where women persevered to protect plants, knowledge, and each other. Often women took risks, whether in careers or in expressing their sexuality, or in speaking to violence; we see these women as pioneers too. They are vital participants in this history even when they remain unnamed. We honor their contributions in this volume by highlighting how the genuine inclusion of women in psychedelics can be messy, complicated, but ultimately rewarding and necessary for developing more inclusive frameworks by first recognizing barriers to participation and differences in experience.

Our book is one of the first of its kind to center women as the entry point into a history of psychedelics.

Music and art emerged as persistent themes in some of the contributions, reminding us of the many ways that women have influenced how one prepares for or integrates a psychedelic experience, in ways that for some time were considered ephemeral or unimportant. We might today recognize that set and setting have become critical features in a psychedelic encounter, but codifying these features initially required crossing boundaries in science. Musicians and music therapists worked in Anglo and European laboratory contexts as well as developed practices in ceremonial settings in places like Peru and Brazil. There was very little overlap between these two parallel developments in calibrating the auditory setting to the mindset, but women feature prominently in both spaces. As our authors explain, these are not merely decorative accompaniments; sonic expressions, whether drumming, singing, or orchestral selections, were part of tapping into emotional aspects of a psychedelic journey. Women like Hermina Browne and Helen Bonny in Baltimore challenged conventional musicology practices when it came to psychedelic therapy to show how music could be incorporated to elicit an emotional reaction. Latin American women honed these techniques but did so on their own terms, under different circumstances. Ayahuasca shamans and Santo Daime leaders keenly recognized the emotional power of music and singing to bring about healing and spiritual responses. Putting these women and their practices together in this volume encourages us to continue breaking down boundaries that have separated these insights across language, discipline, profession, region, and gender. Readers are also reminded that women’s networks and caring roles have been essential for beginning-of and end-of life experiences. In a section about transitions, our authors consider how older plant medicine practices, including those now considered psychedelic, are part of a longer legacy of secret knowledge that was coveted among women healers for birth control, long before feminist marches produced modern vocabulary for women’s bodily rights. There was good reason to keep this information hidden from view, as the penalties for using birth control or seeking abortions carried stiff legal and social consequences for thousands of years. Despite the external pressures to keep this information from view, the relationship between psychedelics and birthing is considered sacred, intimate, and essential. It opens up another pathway of knowledge concerning psychedelic uses, which, perhaps surprisingly, has also influenced dying care. Borrowing practices, theories, and even practitioners from both ends of these life transitions, death doulas and even less formalized practices have benefitted from the wisdom of psychedelic approaches to end-of-life. In a medicalized setting, dying care has often been reduced to managing pain, and psychedelics enter into this discussion as a mechanism for addressing some of the existential and psychological pain and anxiety that accompanies the fear of dying. Our authors explain some of the complex roots of this idea in ways that borrow methods from outside clinical hospital wards, and recenter women in caring roles, while helping to humanize the process of dying. Our book is one of the first of its kind to center women as the entry point into a history of psychedelics. We believe that this task is more than simply adding women to this history. Looking beyond our own borders and assumptions, working with a diverse group of authors and new scholars, we aim to stimulate conversations about diversity and social justice in this expanding field. We hope that by bringing these women’s voices forward we can encourage more ways of changing our minds with psychedelics.

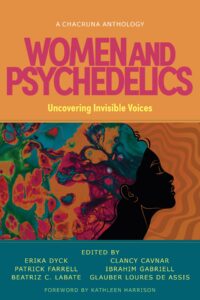

Note: This article was originally published as the introduction to Women and Psychedelics: Uncovering Invisible Voices (Synergetic Press, 2024).

Art by Mariom Luna.

Discover the Indigenous Reciprocity Initiative of the Americas

Take a minute to browse our stock:

Did you enjoy reading this article?

Please support Chacruna's work by donating to us. We are an independent organization and we offer free education and advocacy for psychedelic plant medicines. We are a team of dedicated volunteers!

Can you help Chacruna advance cultural understanding around these substances?