- Ten Tips for Standing in Solidarity with Indigenous People and Plant Medicines - January 18, 2024

- Indigenous Reciprocity Initiative of the Americas: A Respectful Path Forward for the Psychedelic Movement - April 23, 2022

- Supporting Indigenous Autonomy Means Participating in a Story of Relationship - December 10, 2020

Visit Chacruna’s Indigenous Reciprocity Initiative of the Americas.

“Thus stories always, and inevitably, draw together what classifications split apart…we can understand the nature of things only by attending to their relations, or in other words, by telling their stories.”

– Tim Ingold, Being Alive

Out of the shade of pacay trees in the bright sun of a grassy clearing, all dressed in cushmas, parrot-feathered coronas, multicolored bandoliers of seeds and shells and chest bands of woven palm-fibers, shoulders laden with cotton bags and faces adorned with achiote paste, 20 men and women of Tsachopen followed Edu. He led them like a team of synchronized swimmers making a series of self-organizing, self-transforming patterns set to the rhythm of their chant-singing. Everyone played tambores while dancing in a serpentine pattern that spiraled and folded in on itself, only to expand back outward in a seamlessly coordinated dance, their steps set to the drumming of skins and shaking of shells.

This was the first of many lessons Edu taught me about the power of shifting from observer to participant, transforming a perspective of abstraction and alienation into one of communication and relationship.

At first, I didn’t recognize Edu as the man who spoke to me earlier in jeans and a t-shirt, his powerful voice singing the beautiful songs of his ancestors in a primordial timbre. The air carried a subtle vibration as the chorus moved up and down in alignment with the oscillation of steps; just listening gave me a strange feeling, like some immense, ancient force was being summoned, making my cells tingle and verging on an ecstatic buzz which threatened to become a trance-state. Before I was overcome, Edu called to the onlookers without missing a beat, imploring us to join with brazos fuertes. It was profoundly grounding and orienting to clap my hands together in unison with their drums and shakers. This was the first of many lessons Edu taught me about the power of shifting from observer to participant, transforming a perspective of abstraction and alienation into one of communication and relationship.

An Ancient Meeting Place

Tsachopen, where this scene unfolded, is an Indigenous Yanesha community in the high forest of central Peru. On my first visit, I noticed a distinctly changing soundscape as the revving engines, honking mototaxis, and barking dogs of the city gave way to singing birds, chirping insects, and a rustling canopy of tree-covered mountainsides. Leaves seemed to grow bigger the further I went, as conifers and lowland species came together in a liminal space between Montane and Amazon Rainforest. Passing through this ecological zipper reminded me of the mixture of worlds the space represented. The Yanesha, from one of the oldest diverging branches of the Arawak language family (where we get hammock and tobacco, spoken in Haiti at the time of Columbus’ invasion), have lived in their homeland between the lowland Amazon and the high Andes for at least several thousand years (Santos-Granero, 1998; Smith, 2004).

Once at a crossroads between the Inca empire and the rainforest, they have survived the arrivals of Spanish missionaries and conquistadors, Austro-German colonists, and Andean migrants. In the Chorobamba river valley, the sun rises over the Yanachaga mountains, beyond which lies the Palcazu basin, and sets behind the Central Andes. Residents of Tsachopen navigate the implications of living in a biosphere reserve with a growing tourist presence, the convergence of global and local economies, parallel forces of cultural and ecological erosion, external demand for a “traditional” appearance, and a local desire to recover foods and customs of their ancestors.

Yanesha are mindful of the superficial way they are often perceived. Edu, while passionate about his role as a storyteller adorned in traditional regalia, told me being Yanesha was about “living well,” and about a person’s inner world, not their outer appearance.

Yanesha are mindful of the superficial way they are often perceived. Edu, while passionate about his role as a storyteller adorned in traditional regalia, told me being Yanesha was about “living well,” and about a person’s inner world, not their outer appearance. His sister Olinda remembers a time when they had to avoid wearing their cushmas for fear of discrimination. Now, as Edu’s father-in-law Ricardo mentioned to me one afternoon, “when we put on our cushmas, tourists want to talk to us.” Ricardo was an ex-cornesha (community leader) himself. During my last week in Tsachopen, he excitedly showed me his new flatscreen TV, on which we watched a boxing match. For a moment, it seemed contradictory—I suddenly realized that despite everything I knew about colonial presumptions regarding Indigenous culture, I still had lingering fantasies about Amazonia.

Listen to the Forest

The first time I interviewed Ricardo, he invited me to his office, a patch of dirt next to his herb garden and chili-pepper field. He brought out some wooden stools he built himself decades ago, and we sat under the shade of some tall ulcumanos (Podocarpus utilios) in what he called his “designated interview area.” On the other side of the village road, you could see the avocado orchard where we had gathered fruit the day before. He teased me about his rate for interviews being 100 soles (about $30 USD) per hour. In reality, neither he nor anyone else there ever asked me for money, despite all the assurances from certain Limeños that, “all Indians are like that, they will all ask for money.” At one point, deep in conversation, we were interrupted by a lovely chorus of psittacine birds singing above us. Ricardo paused immediately and pointed it out: “Listen to the little parrots,” he said, “it’s not always like this. It’s not so common. It means you are good people.” He said they only sing that way sometimes, and you don’t always see them around.

Whether in his coffee plot, his garden, or his office, he was listening. He was always in communication with a forest that speaks to us whether we hear it or not.

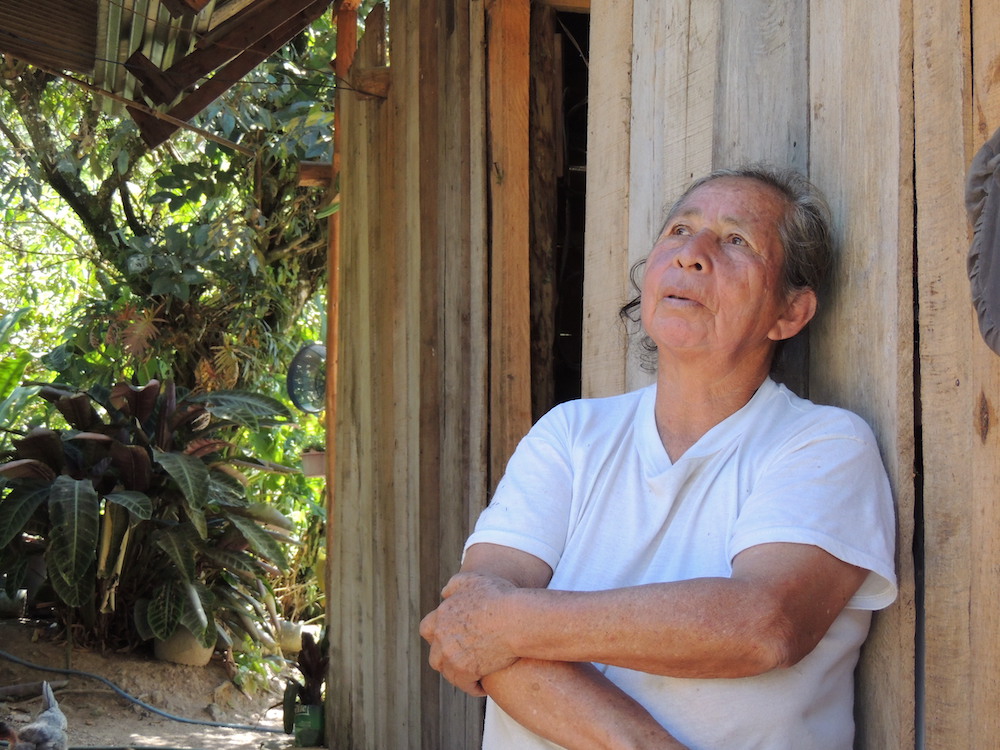

At 72 years old, Ricardo probably remembers when these birds were much more plentiful. Over the decades, he has lived through much of the valley’s deforestation, persecution by Franciscan missionaries, and displacement by colonos. But he welcomed me with open arms and, despite his age, still harvests coffee each day with his wife. Whether in his coffee plot, his garden, or his office, he was listening. He was always in communication with a forest that speaks to us whether we hear it or not.

Join us at Sacred Plants in the Americas II

Ricardo, like most householders in Tsachopen, had a plethora of medicinal plants in his garden. His daughter and her husband Edu are even turning their home into a nursery for lost varieties of food and medicine species. Still, in Tsachopen, there are no more living shamans or curanderos. One of the most popular dances, however, is about the entheogenic brew ayahuasca; Edu told me the song’s Yanesha lyrics describe a time when all Yanesha were sick and dying, so they had to take ayahuasca in order to transform into a giant snake and be cured.

Despite this story which is retold almost weekly, and heartily sung by everyone present, most don’t know the meaning behind its words. They don’t take ayahuasca, but Edu knows it’s a booming business elsewhere in the Amazon and tourists came there seeking it. If I wanted good ayahuasca, he recommended I see a neighboring group, the Matsigenka, who are part of the same language group and who he considers his brothers. He warned me, though, that you shouldn’t take ayahuasca to see visions—that will only cause death or madness—you take it as medicine.

Agency, Authenticity, and Cultural Commodification

Early in my fieldwork, I was invited to the funeral and burial of a community elder that took place on top of a cerro from which you could view the whole Chorobamba valley. I was accompanied by an agronomist from Lima who was preoccupied with taking photos and hoping to get some good pictures for a publication she was working on. At the end of the day, as we left to find a ride back to town, everyone was changing out of their “Western clothes” into cushmas and headdresses in preparation for an event involving visitors from the city government. The agronomist expressed her exasperation that she would miss the photo-op, because it would have made for more “authentic” pictures in her article.

Anthropologist Fernando Santos-Granero (2009) recounts a similar story of a colleague who, after seeing a presentation by Yanesha dressed in cushmas and Bixa orellana face paint, asked if that was traditional Yanesha dress—not even recognizing those same Yanesha when they had changed back into Western clothes. Rather than upholding flawed notions of acculturation and deculturation, Santos-Granero stressed the “merit of recognizing the agency of native peoples” by viewing Yanesha as “skillful consumers of tradition or creative users of traditional elements for modern or postmodern purposes” (2009, p. 478). Global and regional economic processes both connect and alienate Indigenous peoples simultaneously. Commodification of identity should come as no surprise in a world where relationships are increasingly mediated via commodification.

A critic of tourism-driven cultural commodification schemes, Merle Bowen (2016), warns that overreliance on tourism creates dependency, especially in a situation where “environmental service revenues do not benefit local communities but global tourists and local affluent entrepreneurs” (p. 182). Rather than a linear transformation process of Yanesha as reluctant participants in the regional economy, first as laborers, then producers, and now tourism attractions, Tsachopen has combined all these strategies together in its approach. In Ethnicity, Inc., John L. and Jean Comaroff (2009) contend that cultural tourism “has, without doubt, opened up new means of producing value, of claiming recognition, of asserting sovereignty, of giving affective voice to belonging; this not infrequently, in the all-but-total absence of alternatives” (p. 142).

Bowen’s warning is even more prescient today, as a global pandemic continues to threaten the livelihoods of many Indigenous groups who depended on tourism for a large part of their income (Indigenous Tourism Forum of the Americas, 2020). Michael Cepek (2011), working with the Cofan, observes that Indigenous Amazonians recognize “their collaboration with Western institutions as part of a larger exchange with a world that values the environments that they know and inhabit” (p. 513). It is within this context that Yanesha in Tsachopen create and transform their cultural perspectives.

We must examine what brought about this hazardous situation in the first place and acknowledge that the best-case scenario for Indigenous peoples is one where they achieve both more autonomy and less pressure, more options and less constraints.

Yanesha, by necessity, have to steer carefully with an awareness of the possible machinations of conservation narratives and so-called sustainable development. We must examine what brought about this hazardous situation in the first place and acknowledge that the best-case scenario for Indigenous peoples is one where they achieve both more autonomy and less pressure, more options and less constraints. In other words, by supporting Indigenous agency and access to alternative strategies for their own survival in a global market economy that seems to relentlessly reduce their choices.

A Story of Relationship

People in Tsachopen are focused on a renewal of life “as their ancestors lived it,” not as a return to the past, but as a forward-moving, future-oriented process. Along with Indigenous peoples the world over, they find themselves and their territories in the confluence of globalization’s many currents. Their engagement with outsiders represents a well-considered and multi-layered response to these forces in a way that will potentially address the social, ecological, and economic concerns of their communities.

Edu and his family taught me another story we are invited to enter; one where life is always communicating with us, and our well-being is intimately connected to that of every other human being, every organism and organ of the planet.

The forces of Christian colonialism—and its progeny of rationalist, enlightenment philosophy— created Tsachopen’s precarious position, sacrificing local self-determination for the goals of endless expansion. Ultimately, the underlying concepts of Western civilization no longer even serves its own power structures, as they poison the very ground beneath them. The story we were given, that we are separate selves accidentally born into a meaningless world of lifeless particles colliding in pre-determined patterns, is not sustainable; it isn’t even scientific. Edu and his family taught me another story we are invited to enter; one where life is always communicating with us, and our well-being is intimately connected to that of every other human being, every organism and organ of the planet.

There is a very real ethical danger in expecting Indigenous peoples to provide the solutions to the ecological crises industrialized nations created while bearing the brunt of the consequences. Neither Yanesha, nor any other local group, are unchanging monoliths without agency. Supporting the agency and autonomy of Indigenous peoples is part of stepping out of the atrophied mythology of modernity that transforms relations into things and perceives life as a collection of detached objects. Instead, we are reminded that we exist in a network of interrelationship and cooperation that demands our participation.

Sign up for our newsletter

In Tsachopen, a non-profit is supporting a community-led initiative to increase self-sufficiency, regenerate soil health, and strengthen a resilient and robust organic coffee business owned by its Yanesha producers. To learn about their latest project, which is a women-led apiary that will protect biodiversity, provide powerful antibiotic medicine, and create a secondary economic resource for their families, click here.

To support this and other Indigenous-centered, community-driven initiatives that reduce dependency on tourism and represent a range of projects addressing everything from food and environmental health to land-tenure, reforestation, and cultural conservation, including educational, economic, and institutional support, please visit Chacruna’s Indigenous Reciprocity Initiative of the Americas.

Art by Karina Alvarez.

References

Bowen, M. (2016). Who owns paradise? Afro-Brazilians and ethnic tourism in Brazil’s quilombos. African and Black Diaspora: An International Journal, 10(2), 179–202.

Cepek, M. (2011). Foucault in the forest: Questioning environmentality in Amazonia. American Ethnologist, 38(3), 501–515.

Indigenous Tourism Forum of the Americas. (2020, October). Indigenous Tourism Forum. George Washington University. https://www.Indigenoustourismforum.org/

Santos-Granero, F. & Barclay, F. (1998). Selva central [Central jungle]. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution

Santos‐Granero, F. (2009). Hybrid bodyscapes. Current Anthropology, 50(4), 477–512.

Smith, R. (2004). Where our ancestors once tread: Amuesha territoriality and sacred landscape in the Andean Amazon of central Peru. Lima: Instituto del Bien Común.

Take a minute to browse our stock:

Did you enjoy reading this article?

Please support Chacruna's work by donating to us. We are an independent organization and we offer free education and advocacy for psychedelic plant medicines. We are a team of dedicated volunteers!

Can you help Chacruna advance cultural understanding around these substances?