- Psychedelics in the Global South: Relevance and Consequences of the Countercultural Movement in Mexico - February 19, 2025

- United Nations on Psychedelics. The World Drug Report 2023 and the Renewed Interest in Psychotropics Substances - August 24, 2023

- Old Uses of Peyote in Traditional Mexican Medicine and its Inclusion in Official Pharmacopeia - July 5, 2023

Since 1846, the official Mexican Pharmacopoeia recommended the use of peyote extract in “microdose” as a tonic for the heart. In addition, in local traditional medicine the topical application of peyote ointments for various types of pain was and is well known.

This article will review the first investigations about peyote—and its alkaloids—carried out by Mexican scientists during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. This research incorporated Indigenous and popular knowledge on the official pharmacopeias and contributed medical, chemical, botanical, and anthropological knowledge about this cactus and the history of psychedelics.

Peyote’s Long History in Mexico

Peyote has a long history in México and, like other plants and mushrooms, was used in religion, ritual, and medical practices by pre-Columbian societies. When colonizers arrived in the 16th century, these practices were considered idolatries, related to sorcery and the devil and were prohibited and persecuted by the Holy Inquisition and other religious authorities. But even colonial authorities distinguished the uses of peyote that seemed rational from those they considered mere superstitions, namely medical uses that did not include psychoactive effects, including topical uses in ointments and low dose heart tonics.

even colonial authorities distinguished the uses of peyote that seemed rational from those they considered mere superstitions, namely medical uses that did not include psychoactive effects, including topical uses in ointments and low dose heart tonics.

By the 19th century, psychoactive plants were analyzed in Mexican institutions, such as the National University, National Institute of Medicine, and the Mexican Pharmaceutical Society, as well as in other parts of the world, including in the works of Louis Lewin, Arthur Heffter, Havelock Ellis, and a large number of other writings on the subject by botanists, anthropologists, philosophers, and artists.1

It must be considered that the studies carried out at the National Institute of Medicine sought to transform the traditional medicine markets into a regulated pharmaceutical, supported by scientific experimentation.2 The first national Mexican pharmacopeia (1846) had the objective of determining the appropriate conditions and dosage for prescribing drugs, chemical products, and other pharmaceutical preparations and included peyote. It mentioned that a “fluid extract” of peyote could be used as a cardiac tonic, taking up to 30 drops three times a day.3

Early 20th Century Peyote Research and Mescaline Synthesis

By 1904, the chemist Juan Manuel Noriega published his book Historia de las Drogas, in which he pointed out that small doses of peyote increased energy and raised blood pressure, but that it could also cause “visual hallucinations that consist of a moving kaleidoscope of colors.”4

In 1913, the National Institute of Medicine published an article titled The Peyote Study that mentioned that Indigenous people apply it externally to treat snake bites, burns, wounds, and rheumatism, for which, they chew it or simply moisten it in the mouth before putting it on the injured parts. After several experiments, in which peyote tincture was administered to healthy people and to people with heart problems, it was concluded that peyote has effects on breathing, the heart, and the brain. At the level of the nervous system, it was only mentioned that several people had dizziness, nightmares, delusions, and hallucinations. In a derogatory tone, this paper also mentioned that “the studies carried out at the National Medical Institute do not confirm many of the vulgar beliefs about the effects of peyote.”5

After several experiments, in which peyote tincture was administered to healthy people and to people with heart problems, it was concluded that peyote has effects on breathing, the heart, and the brain.

1919 marked the first synthesis of mescaline: “the first psychedelic to be created in a laboratory.” This news did not take long to reach Mexico and quickly influenced the ways in which research was conducted with peyote, not only in the use of extracts, but also in how the studies went to the field of psychiatry and psychopharmacology. The isolation of mescaline changed its relationship with the peyote plant, consequently also isolating it from its cultural and traditional uses.

By 1921, the Latin-American Pharmacopoeia of 1921 referred to the uses of peyote as a heart tonic and brain stimulant, for which two tablespoons of a 10% tincture were prescribed. In addition, this manual mentioned that “peyotina” was used as an intravenous tranquilizer for various cases of insanity.6

The Isolation of Three Peyote Alkoloids by Mazzotti

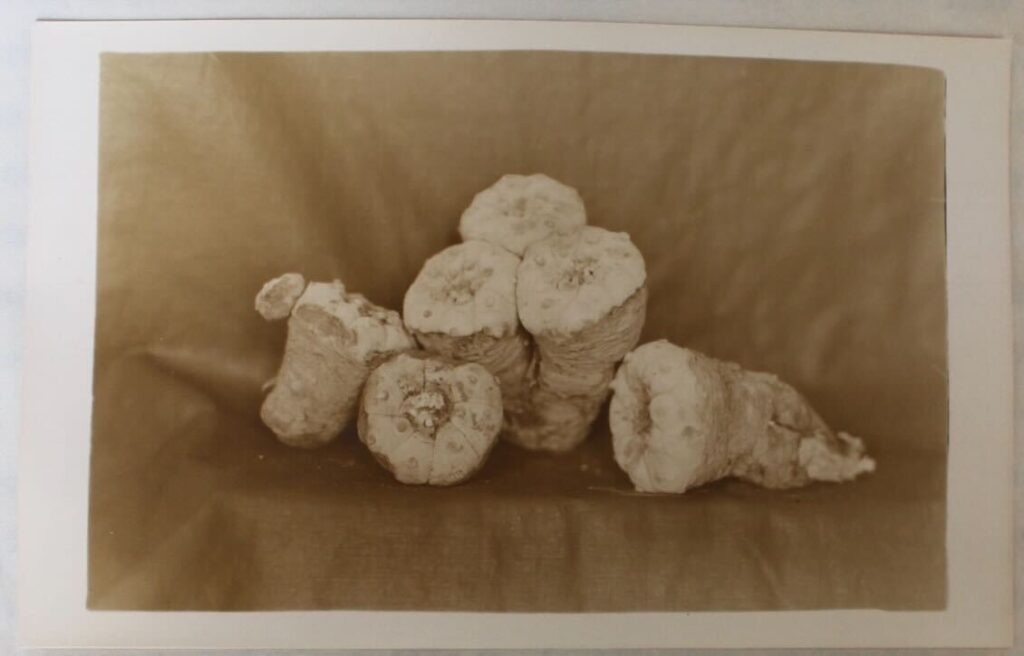

A few years later, in 1926, the doctor José Mazzotti wrote a thesis entitled Brief Considerations as a Contribution to the Study of Peyote.7 This doctor studied the physiological effects of peyote on animals and humans, including his own self-experimentation. The first challenge that the doctor faced was to obtain the specimens of the plant, even while in Mexico, he pointed out that he had requested the plant from various States and he can only find it in the towns of Fresnillo, Sombrerete and San Juan de Guadalupe in the State of Zacatecas.

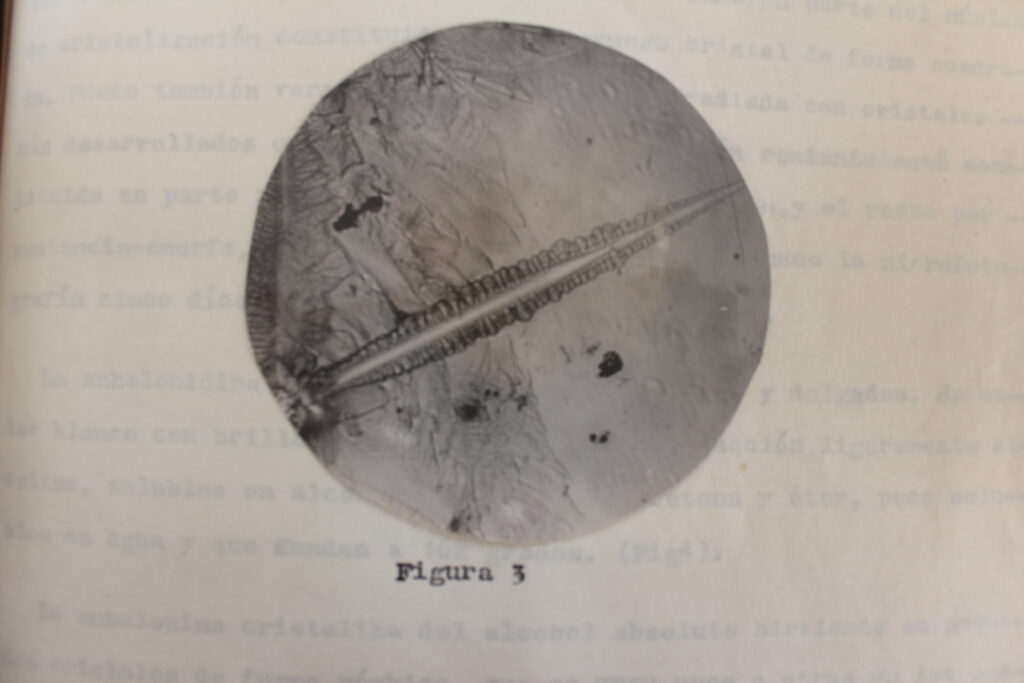

Mazzotti included historical and botanical descriptions of the plant and a chemical analysis. Of which, he managed to isolate three of the alkaloids of the plant: anhalodine, anhalonine, and mescaline. This last substance was described as “the mescaline. It is a thick, bitter liquid, dark brown in color, with an alkaline reaction, soluble in water.”

This last substance was described as “the mescaline. It is a thick, bitter liquid, dark brown in color, with an alkaline reaction, soluble in water.”

To understand the physiological action of this Mazzotti cactus, he carried out experiments with animals—dogs, frogs and turtles—and humans, including himself, in which he reported the effect of the three alkaloids he managed to isolate on the heart, blood pressure, and respiration. He concluded that the effects of peyote on the human body and brain were evident, but more studies were necessary.

He self-applied three mescaline injections with the following doses: 0.04, 0.04, and 0.02g., in that order. He clearly described his sensations, which began with intense pain in the area of the sting, which turned into anesthesia that gradually spread to the entire body, followed by pressure in the temples and chest, anguish, and fear of dying; these unpleasant sensations disappeared after 10 minutes, followed by strong relaxation, auditive distortions, and “visions of white lines intersecting with others to form various shapes.” With the last injection, the visual distortions increased, the doctor described: “The figures that appear before my eyes when I close my eyes are very variable, mobile and shortly after they are accompanied by colorful sparks, like a multitude of rockets before my eyes” until he fell into a deep sleep.

With the last injection, the visual distortions increased, the doctor described: “The figures that appear before my eyes when I close my eyes are very variable, mobile and shortly after they are accompanied by colorful sparks, like a multitude of rockets before my eyes” until he fell into a deep sleep.

Prohibition on the Horizon

In the decades following Mazzoti’s research, experiments with peyote and mescaline leaned towards psychiatric perspectives, and by 1971 they would also face prohibition. However, in contemporary records, on file with Digital Library of the Mexican Traditional Medicine, peyote uses continued to be reported as topicals for muscular pain, bruises, fractures, and insect bites, as well as a poultice for toothache and eaten in small doses as a tonic and restorative agent.

To conclude it is important to highlight that peyote it is not only a medicine and a sacred plant, but also a natural species that is in danger of extinction. However, I consider it important to explore its diverse uses in order to support legal discussions and its conservation.8

Art by Mariom Luna.

Join us for our Roots of Psychedelic Therapy: Shamanism, Ritual and Traditional Used of Sacred Plants course, August 8th – November 21st, 2023

Notes

1 Jay, M. (2021), Mescaline. A Global History of the First Psychedelic, London Yale University Press. 7-8.

2 Dawson, A. (2018), The Peyote Effect. From the Inquisition to the War on Drugs, Oakland, University of California Press. 23-25.

3 Farmacopea Mexicana (1846), México, Academia Nacional Farmacéutica. 336-337.

4 Noriega, J. (1904) Historia de las Drogas, México, Instituto Médico Nacional, 511.

5 Estudio relativo al Peyote, (1913), México, Instituto Médico Nacional. 61-63.

6 Alfonso L. Herrera, (1921), Farmacopea Latino-Americama, México, Talleres Gráficos de Herrero Hermanos.

7 Mazzotti, J. (1926), Breves consideraciones como contribución al estudio del peyote, [Unpublished medical thesis] Universidad Nacional de México.

8 Labate B & Cavnar C. (2016), Peyote, History, Tradition, Politics and Conservation, Santa Barbara, California, Praeger.

Take a minute to browse our stock:

Did you enjoy reading this article?

Please support Chacruna's work by donating to us. We are an independent organization and we offer free education and advocacy for psychedelic plant medicines. We are a team of dedicated volunteers!

Can you help Chacruna advance cultural understanding around these substances?