- Why Land and Ecology Matter for Global Psychedelics - January 25, 2024

- Coming of Age in the Psychedelic Sixties - March 15, 2022

- Psychedelics, the War on Drugs, and Violence in Latin America - March 10, 2022

By Diana Negrín with Yvonne Negrín

“If you can just get your mind together

Then come on across to me

We’ll hold hands an’ then we’ll watch the sun rise from the bottom of the sea.

But first,

Are you experienced?

Have you ever been experienced?

Well, I have.”

– “Are you Experienced?” Jimi Hendrix (1967)

The 1960s has been characterized as a period that created a cultural and sociopolitical convergence of such magnitude that young people from various households of the post-war period took the leap forward and explored new ways of co-living, making art, and thinking about political life. Psychedelics were an important part of this courageous generational leap just at a moment when United States hegemony struck at precepts of human rights abroad and used every weapon to oppress justice and dissent domestically. The stranglehold of white supremacy, patriarchy, and permanent war was weakened by the new spaces for social life where sometimes psychedelics played an assisting, if not catalyzing, role. My mother, Yvonne Negrín, née da Silva, was one of countless young women who found herself looking through the mirror of this cultural moment, aided by the singularity of the era and two remarkable geographies: New York and California.

Born in 1947 in White Plains—north of New York City—Yvonne was raised by what could be called the prototype parents of the post-World War II era. Her father, Alexander Da Silva, was born in Brooklyn to Luso-Brazilian immigrants and was one of tens of thousands of men who went to war in the early 1940s and found their battlefield in German prison camps. Alex returned from war and became a postal worker and continued occasional tree pruning alongside part-time television and garage door repair. Yvonne’s mother, Martha McGuire, was from rural Ohio and moved to Stanford, Connecticut during the war years. There, she and her sisters went to work at PerkinElmer, where they produced precision optics. Once married, Alex and Martha would soon move further upstate New York to Ossining where they would raise Yvonne and her three younger brothers. Yvonne describes her household as a very typical middle-class family for the era, with ample freedom to run around as fathers labored at work and mothers toiled at home in a typical nuclear family format.

“I GOT INTO FOLK MUSIC, I THINK BOB DYLAN WAS A HUGE INSPIRATION AND JOAN BAEZ. THE SONGS THAT THEY WROTE OR SANG, THE ISSUES THAT THEY BROUGHT UP ABOUT INJUSTICES; THERE WAS A LOT OF FOOD FOR THOUGHT.”

Yvonne Negrín

While her parents were always progressive in politics, she and her brothers all eventually questioned their conservative Catholic upbringing. For Yvonne, the first elements to unsettle the still unnamable cultural moment came through her connection to music in her early teens:

“I think I just became aware of the reality of things, I got into folk music, I think Bob Dylan was a huge inspiration and Joan Baez. The songs that they wrote or sang, the issues that they brought up about injustices; there was a lot of food for thought. It was a pretty segregated situation growing up. I don’t remember if we even had an African-American student in the Catholic school that I went to, there were a lot of Italians and Irish Catholics.

And then also when I was about 15, I met Sonny Sharrock who was a guitarist, he worked in the record store down on Spring Street in Ossining and used to sell me my 45 RPM records. A lot of it was Motown, but he was the one who turned me on to jazz and introduced me to people that I started hanging out with. By the time I was 18, I moved out of my parents’ house and into an apartment and I remember that Sonny turned me on to John Coltrane and I started going to Manhattan with a friend of his that was also from Ossining… we went to lofts where jazz musicians gathered to jam and that was my introduction to jazz and Black culture, and I formed some very close and very good friendships.

So between the folk music scene and the jazz scene, it all really opened up my mind. I think the first time I smoked grass was listening to John Coltrane’s Ascension. That was a mind opener! Then I moved to Manhattan to the Lower East Side where there was a lot going on during those years. I met a lot of people, among them Abbie Hoffman, who was very interesting, and Frank Zappa.“

Discover the Indigenous Reciprocity Initiative of the Americas

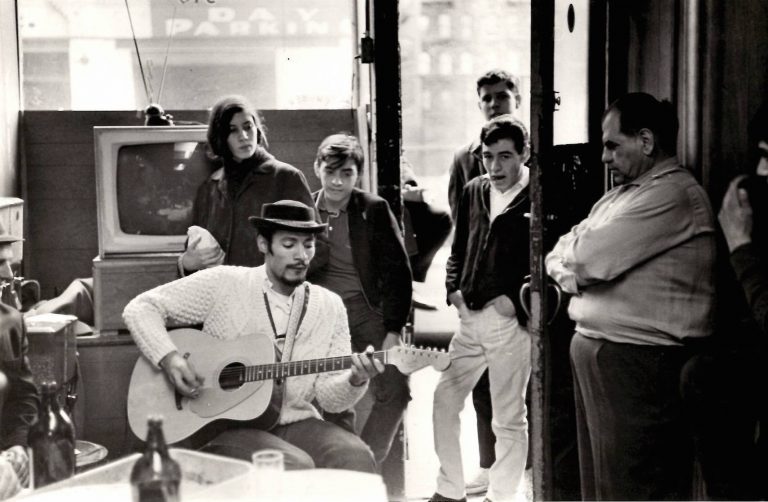

It was in this way that Yvonne moved from listening to Mary Wells and Marvin Gaye to trying out her own skills playing folk guitar, each time drawn further in by the musical experimentation and political commentary that emerging artists were pushing in the heart of New York City.

We are talking the United States of 1965—a year that began with the swearing in of President Lyndon B. Johnson and the assassination of Malcolm X; it continued with the deployment of US Marine ground troops in Vietnam and the Alabama State Trooper attack in Selma, known as “Bloody Sunday.” The year’s top musical albums included Rubber Soul by The Beatles, Highway 61 by Bob Dylan, Farewell, Angelina by Joan Baez, and A Love Supreme by John Coltrane. Yvonne was one of many brave young women who moved to the Big Apple. In her case, she landed a job at Look magazine and ventured into the be-ins at Central Park, the epic Fillmore concerts, and the small jazz clubs where she continued to be cued into the heart and soul of the “Psychedelic Sixties.” It was no small feat for a young woman from a Catholic household to make this countercultural shift and truly believe and come of age within it.

Playlist of the Psychedelic Sixties (1965)

Certainly marijuana had already become deeply criminalized and portrayed as the antithesis to the white, nuclear, hard-working family where new canned food recipes and afternoon cocktails and cigarettes were the permitted stimulants. During the following three years, Yvonne lived in the Lower East Side and navigated spaces where various stimulants, from uppers like methamphetamines and downers like heroin, were taken alongside the increasingly popular use of psychedelics like LSD, STP,1 and DMT.2 She recalls how it was the children of the middle and upper-class white families who she remembers using psychedelics. Most of her friends in jazz circles seldom touched psychedelics—this includes her recollections of Sun Ra, who lived across the street and who she recalls being a “natural space cadet” who probably did not need the stimulation of psychedelics to arrive at his creations and political formulations. Without doubt, Yvonne emphasized that “there was a lot of experimentation in general whether it was with or without psychedelics, people were experimenting; the people you were around were being creative.”

“IT WAS THE IDEA OF PEELING AWAY THE LAYERS OF A FACADE AND GETTING DOWN TO MY ESSENCE, WHO I REALLY WAS.”

Yvonne Negrín

As a young and independent woman, set and setting were quickly established as important factors:

“My first LSD trip was on Sandoz’s acid and it was given to me by this guy that I had met. His interest was seducing me, which didn’t work, I got very upset. I was interested in trying LSD, I had heard a lot about it but I did not know this guy’s intentions. And so halfway through the trip I split his apartment, I left and went walking home totally stoned, walking through the Lower East Side. And on my way home I stopped in The Annex, which was a bar that was near my house, I wanted to get something to drink, a glass of water, I was thirsty and an acquaintance hits on me and it was like a nightmare. Eventually I got home and once I was in my own space I was fine. Later I felt LSD was useful for reflection, inner-reflection. I remember deciding on that first trip that I was really not turned on by the idea of makeup. I remember at one point looking in the mirror and it seemed like my mascara was really amplified. I stopped wearing makeup after that. It was the idea of peeling away the layers of a façade and getting down to my essence, who I really was.”

This was the beginning of Yvonne’s intuitive and very personal work with psychedelics.

Young people experimented in park gatherings, concert halls, and in their city apartments—many of these youth participated in the continuous public protests against the war and ongoing racial segregation. Yvonne fondly recalls counterculture figure and activist Abbie Hoffman’s group, The Yippies, and the gatherings she did and did not attend that marked the beginning of a more radical wave of social movements and the US government’s ensuing clamp down on activist leaders.

Experimental use of drugs ran parallel to mainstream society and politics, while the excitement of new philosophical doors opening began to close as many people started using larger doses of psychedelics and experienced infamous “bad trips” and lingering flashbacks:

“STP then hit the scene, and it was interesting because people were having very heavy trips on STP, it was like a psychedelic trip amplified; not only were they having heavy trips but they were having uncontrolled flashbacks. I was very curious about STP and the only time I took STP was in New York City while I had my last apartment there I wanted to try it, but being the conservative girl I was, I decided ‘we’ll I’m only going to try some of this,’ so I broke the tablet in four pieces and I took a quarter of a dose, and I had an absolutely wonderful experience. A great trip! And many, many, years later I was talking to Sasha Shulgin, and I asked him why so many people were having such horrible trips on STP and that I had a wonderful trip one, but I told him that I’d only taken a quarter of a tablet. He said “well you actually took what everybody should have been taking!” People were overdosing on STP! And that was the problem, you know, even with LSD, it went from being tablets of 125 micrograms to 250 mics to 500 mics. They were splitable tabs but people would take the whole 500 and blow their minds wide open.”

Further, Yvonne recalls the way speed and heroin created “lost souls” and how New York “deteriorated” with violence and a generally cold social atmosphere. In contrast, sunny and free-loving California was on many peoples’ minds and in 1968 Yvonne journeyed west, landing her first apartment in Lagunitas with blues singer Kathy McDonald who often sang with Big Brother and the Holding Company.

“I mean San Francisco was a really happening place in the music scene, which extended to the psychedelic scene, because psychedelics were really happening in the Bay Area. I really loved music and I was interested in potentially being a sound engineer and I would sit with Dan Healy who is the one who did all the mixing of early Grateful Dead, Steve Miller, and Van Morrison albums. I would sit in the sound room and I got to watch a lot of albums actually be recorded in the studio.”

In the Bay Area, Yvonne met her future husband, Juan Negrín (b. Mexico City 1945–d. Oakland 2015), who shared an interest in the political and cultural revolution that appeared to be underway. Juan had also come from the jazz clubs of New York and was optimistic about the potential LSD could have for helping people find a deeper political and spiritual awareness. During that time, Yvonne became a friend of psychedelic chemist, Alexander (Sasha) Shulgin. Sasha, was active on UC Berkeley campus at the time and was well into his explorations of psychedelic compounds. Yvonne would often provide Sasha with samples of the substances that people were trading and selling on the streets. He would in turn test them in his personal lab in Lafayette and report back on whether they were pure or doctored substances, and thus worthy of consuming or not. She lovingly remembers Sasha as a mentor and although she never “tripped” with him, they shared stories about their respective adventures in altered states. On one occasion, Yvonne acquired ibogaine, a plant medicine that she had read about. She provided Sasha with the sample without disclosing what it was and to his own surprise he called her and exclaimed: “Where did you get this?! This is ibogaine!”

And yet, California by 1970 was a changing landscape. On the west coast, social movements had been attacked and degraded while the world of culture and drugs shifted into a darker future. In 1970, president Richard Nixon continued to escalate the Vietnam War. In the United States the Kent State shooting, the Weathermen bombing, and an escalating counterintelligence hunt against the Black Panther Party. In the world of music, The Beatles broke up and some of the top albums of the year were Morrison Hotel by The Doors, Black Sabbath’s debut album, the Grateful Dead’s Workingman’s Dead, and Bitches Brew by Miles Davis. For Yvonne, the world of drugs and psychedelics emulated the darkness of the moment. On the other hand, policing in the years that led to the formal declaration of the War on Drugs also created a deteriorating and unsafe scene for psychedelics. Many friends and acquaintances were persecuted, in many cases on conspiracy charges. One dear friend died mysteriously after an encounter with a narcotics agent.

Join us for our next conference!

Yvonne laments how many people produced psychedelics for pure profit, while only a few had the skilled knowledge and ethical commitment to create pure substances. Others she identifies as “bad actors,” who she feels used the rising popularity of drugs as a ticket for fast money. One such breaking point was a man she caught cutting LSD with speed to then sell as mescaline. Sasha would often tell her that one never knew the contents of the pills circulating.

It was in 1970 when Juan took Yvonne to meet his father in Guadalajara, Mexico, and there, they came across Wixarika artwork. Could it be that the deep spiritual and philosophical answers they had been searching for had led them to their next journey? Over the following years, Yvonne became closely connected to Wixarika communities and participated in culturally mediated uses of another psychedelic: the peyote cactus. Over the following decades, she and her husband founded a series of nonprofits to support the art and territorial autonomy of the Wixarika. In the 1990s, when she returned to live in the Bay Area, Yvonne continued to connect with the Shulgins and many other local psychonauts to sustain critical discussions on the potential of psychedelics, legislative change, and the delicate balance that it all entailed.

New York was the bedrock that nurtured Yvonne’s curiosity; it led her to the nodes of artistic production in Manhattan and then to the San Francisco Bay Area where she met her lifelong companion, Juan, and continued the experience of linking altered states with deepening commitments to art. This Bay Area then became the springboard to the Western Sierra Madre and the lowlands of Nayarit, a geography that cemented Yvonne’s following fifty years of work knitting together culture and ecology. To date, she continues to direct the Wixarika Research Center’s archival and grassroots work.

This article originally appeared in Spanish on Chacruna Latinoamérica: “Despertares en la era de los ‘sesentas psicodélicos’ (con Yvonne Negrín)”

Take a minute to browse our stock:

Did you enjoy reading this article?

Please support Chacruna's work by donating to us. We are an independent organization and we offer free education and advocacy for psychedelic plant medicines. We are a team of dedicated volunteers!

Can you help Chacruna advance cultural understanding around these substances?