Psychedelics reform is coming in hot, with two key wins at the ballot box last week: Washington D.C. approved decriminalization of psychedelics and Oregon approved both its psilocybin therapy model and broad drug decriminalization. The cities of Oakland, Santa Cruz, Denver, and Ann Arbor have also decriminalized psychedelics, and similar efforts are underway in over 100 other cities across the US.

Over the next few years, at a rapid pace, Californians will learn about psychedelics and why doctors, scientists, therapists, and community activists are calling for safe access and the end of criminalization.

Over the next few years, at a rapid pace, Californians will learn about psychedelics and why doctors, scientists, therapists, and community activists are calling for safe access and the end of criminalization. Indeed, as they always have, voters in the Golden State will play an integral part in a global conversation about legalization and regulation of emerging medicines and markets.

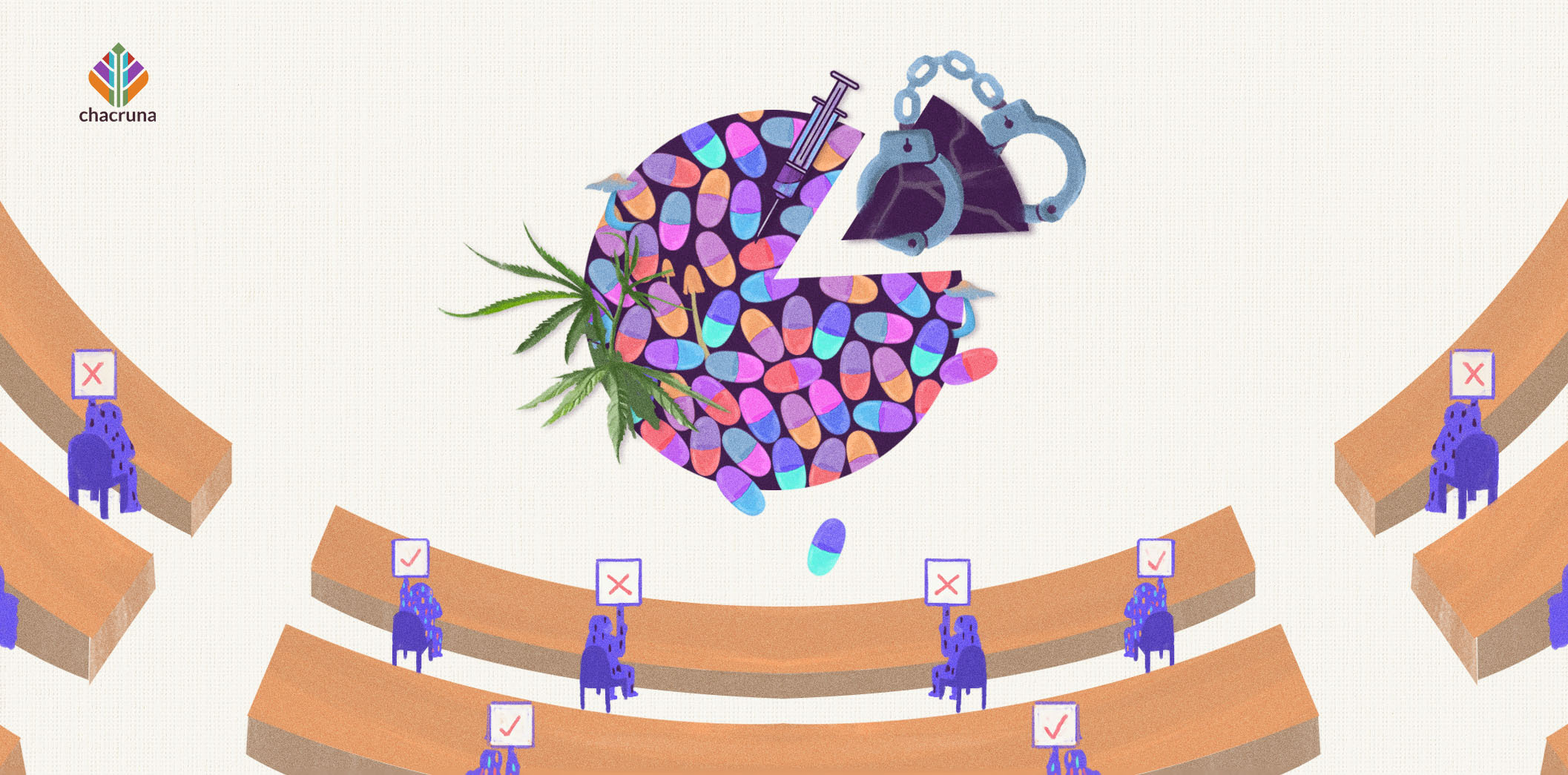

The ingredients that will be baked into California’s future psychedelics legislation will be made of the stuff that has brought psychedelics back into the public eye, but California’s appetite to pass legislation will be propelled by broader public health and drug policy reform. This is why California’s future psychedelic legislation should start with decriminalization of all drugs for low-level possession, rather than limit decriminalization to psychedelics only. To unpack this, let’s look at how psychedelics moved into the mainstream and why legislation that takes a psychedelic-exceptionalist (*) approach falls short.

Psychedelics are therapeutic medicines for public health problems that are at crisis proportions.

The mainstreaming of psychedelics is the result of a perfect, beautiful storm of science and culture that has finally made landfall. Scientific and medical research, started in the 1950s, was seemingly wiped out with Nixon’s War on Drugs in the 1970s, but gained traction again in the 1990s (thanks to the tireless work of medical-practitioners and advocates), and has now reached an irrefutable tipping point. Psychedelics are therapeutic medicines for public health problems that are at crisis proportions. Since COVID, there’s been a dramatic rise in the US in anxiety and depressive disorder, substance abuse, and suicidal ideation. Today, one out of three Americans has signs of clinical anxiety or depression. Prior to COVID, it was one out of five. Last year, nearly 70,000 Americans died from drug overdoses, and it’s getting worse. Study upon study from public and private institutions worldwide show the benefits of psychedelics for treatment-resistant depression, drug and alcohol addiction, and PTSD, among other conditions. The U.S. Food & Drug Administration’s grant of Breakthrough Drug Therapy Designation to MDMA and psilocybin, and its approval of ketamine last year, marks federal endorsement for certain psychedelics as therapies.

Join us at Sacred Plants in the Americas II

The legalization of cannabis has also played a pivotal role in the public’s openness to psychedelics. Cannabis has gone from demonized and on-the-fringes, to socially acceptable for its medicinal value. It is now found packaged-neatly in homes across California, other legal states, and, increasingly, the rest of the world. The designation of “cannabis as an essential product” by local and state jurisdictions earlier this year meant further sloughing off of old anti-cannabis attitudes, which has made many more people question the reason for cannabis’ illegality to begin with. In fact, this rapid change in attitude and laws today finds the vast majority in the US—a whopping 91%—believes cannabis should be legal for either medical or adult-use, and bipartisan voters carried that message to the polls with five more states legalizing cannabis in some form this last election.

The U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration still lists cannabis, MDMA, and psilocybin, along with a whole host of other drugs, including LSD, heroin, mescaline, and DMT, as “Schedule I,” carrying the highest criminal penalties.

Meanwhile, on the federal level and, typically, out of step with social progress, the War on Drugs is still going strong. The U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration still lists cannabis, MDMA, and psilocybin, along with a whole host of other drugs, including LSD, heroin, mescaline, and DMT, as “Schedule I,” carrying the highest criminal penalties. The US spends more than $47 billion every year on the drug war, millions of people in the US are still being arrested and incarcerated for drug-related offenses, and the majority of Americans are sick of it. It is well understood that the War on Drugs is a war against people of color and other marginalized groups. This, along with Black Lives Matters and the murders of George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, and countless others, has brought the US to a pivotal point of racial and cultural reckoning that is driving criminal justice and drug policy reform. Today, the call for major drug policy reform is no longer limited to impacted communities and advocates; it’s in the political centerstage. And while the national conversation about the War on Drugs does not generally mention “psychedelics” per se, the public’s ever-increasing skepticism about the government’s drug laws further contributes to the mainstreaming of psychedelics.

It is within this social and political moment, and because of public health and changing public attitudes, that California will craft its psychedelics legislation. Our legislation (or ballot initiative) will likely include regulated access to certain psychedelics in some form or fashion. Perhaps it will be similar to the recently-passed Oregon psilocybin therapy model, which is tightly-prescriptive and only allows access to psilocybin through specialized treatment centers. Perhaps we will see the sale of certain psychedelics within a state-regulated system, similar to (but hopefully markedly different from) cannabis. The nuts and bolts of what legalization and regulation should look like in California is a many-layered discussion that policymakers and policy-changers will continue unpack and construct in coming years, and broad decriminalization of all drugs—and not just select psychedelics—must be part of our future legislation. And California wouldn’t be the first.

Oregon just took this bold and needed step. It passed Measure 110, which removes criminal penalties for low-level drug possession and funds harm-reduction, addiction treatment, and recovery centers. Oregonians are facing their addiction problem as a public health issue, to be treated humanely rather than criminally. In 2001, Portugal recategorized personal possession of drugs as administrative, rather than criminal, violations, and expanded drug treatment and rehabilitation. In Portugal, it was an addiction and public health crisis (heroin plus HIV rates), coupled with half the population in prison there for drug-related offenses, that inspired that then-radical step. Since then, the Netherlands, the Czech Republic, and Switzerland have followed suit.

Many of us who work on psychedelic policy reform are inspired because psychedelics have saved our lives and held us in our healing journey through addiction, anxiety, depression, and generational trauma as marginalized POC trying to live in America.

The talked-about gap between psychedelic advocates and the broader criminal justice movement puts the two in separate camps. But that’s just a story; there aren’t two camps. Look around at the pot boiling over—social, political, and racial unrest—and then look at why psychedelics offer such promising therapeutic benefit and have been used by cultures across the globe for many thousands of years. Psychedelics provide healing to our inner and outer world, and we need it. Many of us who work on psychedelic policy reform are inspired because psychedelics have saved our lives and held us in our healing journey through addiction, anxiety, depression, and generational trauma as marginalized POC trying to live in America. Indeed, clinicians are developing treatment tools for psychedelic therapy used to treat race-based trauma.

If we go forward with psychedelic legislation in California that decriminalizes select “good drugs,” legalizes some form of access largely inaccessible to the majority (à la Prop. 64, California’s cannabis legalization initiative) and leaves aside decriminalization of all drugs for low-level possession, we will carry the War on Drugs’s mantle forward. Psychedelic exceptionalism is a narrow view that only those with privilege can hold comfortably. For a reform movement that holds public health and healing as a driving force, any meaningful California legislation must include broad decriminalization.

Those of us who have worked on legislation and policy reform in California well know that it’s a circuitous route. Perhaps as legislation is drafted, political alliances made, polls analyzed, and as policy-reform leaders scrutinize the data, decriminalization and regulation will be pulled apart and rolled out in stages or hand-in-hand. Indeed, a psychedelic-exceptionalist policy approach may seem an easier lift and more politically salient in the storytelling arena of the public square. But that’s just a story too. In fact, the rock-bottom we find ourselves in—this public health, racial, economic, and political crisis—lends itself less to incrementalism and more to what may, at first glance, appear as radical and out-of-the-box.

Insisting that future California psychedelics legislation include decriminalization of all drugs for low-level possession and funding for addiction treatment and recovery services is a call for a change in orientation from punitive drug policies and psychedelic exceptionalism to rehabilitation and inclusion. Psychedelics are about public health and personal and social healing, and the crafting of any future California psychedelics legislation must come from that place.

Art by

—

(*) Note:

Psychedelic exceptionalism, I argue, is a narrative that describes psychedelics as “good drugs” and other drugs, like heroin and crack cocaine, as “bad drugs.” The glaring problem with this narrative is that it runs largely along racial and socioeconomic lines and continues the War on Drugs’ ethos by stigmatizing and criminalizing the people who use “bad drugs,” rather than focusing on treatment and social conditions that underlie the drug use.

A shorter version of this article appeared here.

Take a minute to browse our stock:

Did you enjoy reading this article?

Please support Chacruna's work by donating to us. We are an independent organization and we offer free education and advocacy for psychedelic plant medicines. We are a team of dedicated volunteers!

Can you help Chacruna advance cultural understanding around these substances?