- Introduction to Women and Psychedelics - July 26, 2024

- Global History of Psychedelics: A Chacruna Series - October 4, 2023

- Can Psychedelics Promote Social Justice and Change the World? - August 30, 2021

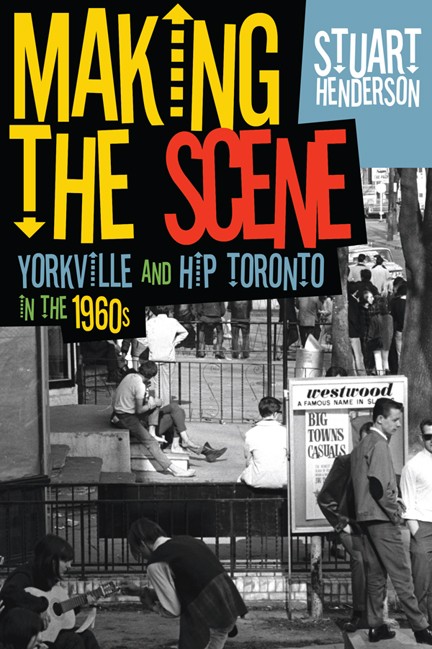

I had the pleasure of sitting with author and film-maker Stuart Henderson recently, to ask him about his work on the history of the counterculture in Canada. Henderson is the author of Making the Scene, an engaging book that takes readers to the epicentre of Canada’s hippie culture in Yorkville, Toronto. While this modest stretch of urban space in the middle of Canada’s largest city doesn’t readily compare with the likes of the American counterculture scenes in places like Haight-Ashbury or Greenwich Village, Henderson explains that Yorkville brought its own twist on being hip in the age of countercultural radicalism, sexual revolutions, and drug experimentation.

Toronto after the Second World War remained a predominantly white city, populated mostly by Protestant, Anglo-Saxon types. But, after the war, that began changing as more immigrants, especially those from Eastern Europe, Italy, and Hungary came to Canada seeking a different future. Many of these families settled downtown, particularly as white Torontonians moved outwards into the suburbs. Henderson explained that this story plays out across North America with the rise of the suburbs, and it also created new urban subcultures particularly as new ethnic fashions moved into the city; in this case, bringing a coffee house culture to downtown Toronto. The coffee houses became an important feature, attracting back some of those suburban youth who wanted to check out this cultural phenomenon.

The Scene

“Yorkville was as much an idea as a place. It was a place of experimentation, and a place of freedom.”

Yorkville really was a scene. In the 1960s this small urban enclave—a mere two blocks—became home to a blossoming countercultural scene. It was home to coffee houses, art studios, places to hear live music (from the likes of Gordon Lightfoot, Murray McClauchlan, Buffy Sainte-Marie, Ronnie Hawkins, Robbie Robertson, Neil Young, the immortal Joni Mitchell), not to mention apartments that became home to transient youth as well as permanent residents. But, above all, Henderson explains that Yorkville was as much an idea as a place. It was a place of experimentation, and a place of freedom. Blending elements of exoticism with bohemianism and radicalism, residents and visitors began to participate in a Yorkville scene as an experimental space. People came to Yorkville to test out different ways of performing an identity: experimenting with sex, drugs, music, fashion, even hair cuts. If for some being a hippie meant avoiding hair cuts, for others it allowed for a kind of sexual freedom, or encounters with exciting drug experiences—experiences that were prohibited and shunned elsewhere in the conventional urban landscape. Yorkville itself, was a gateway space to a bohemian world of consciousness, radicalism, anti-colonialism, and anti-racism activism. But, Henderson cautions, that this hip world was also riddled with a tangle of contradictions about race, class, and gender.

The media focus on Yorkville helped to amplify its significance, beyond reality. Journalistic accounts created an impression of this place as exotic, liminal, and enticing—especially for bored white Torontonians. Henderson described it as a “cauldron of swirling identities” as people tried on new ways of expressing themselves and consuming radicalism. Drugs were one aspect of this cauldron. In fact, one particular drug bust captured major news attention. Ultimately, it boiled down to a single marijuana cigarette, possibly planted by Toronto police, but the proverbial genie was out of the bottle. Now Toronto readers knew that Yorkville was a place to find drugs. Drug dealers and seekers moved in. Marijuana wafted through the streets, but soon seekers could find psychedelics (and fake psychedelics—like selling blank pieces of paper to tourists seeking acid), and by the end of the decade, amphetamines and speed were becoming part of an epidemic that characterized the hippie culture.

“Women in this space, were … referred to as, Hippie Girls. And, the freedoms and experimental opportunities for these Hippie Girls were sometimes more complicated than those afforded to the hippie (men).”

Henderson examined a wide range of news, journalism, film, and media accounts of hippies in the 1960s. Remarkably, he found that the idea of the hippie was defaulted as male. In other words—hippies, were men. Women in this space, were instead referred to as, Hippie Girls. And, the freedoms and experimental opportunities for these Hippie Girls were sometimes more complicated than those afforded to the hippie (men). Hippie Girls could still enjoy some of the freedoms of a Yorkville visit, or even adopt a Yorkville attitude themselves. That is to say, some women embraced the idea that they could have sex with whomever and whenever they chose. They could also participate in the drug culture on their own terms. But, Henderson explains that while these attitudes were expressed and celebrated, there was still a double standard in place when it came to the freedoms afforded to the Hippie Girls—hippie (men) could weaponize this freedom of choice, creating new pressures for women to have sex, or even for cases of sexual violence. As drugs and sex co-mingled, gangs and underground networks formed, creating new cultures of violence and reinforcing older ideas of patriarchy. As Henderson put it, the scene in Yorkville created a “funky comradery of outlaws.” So, while these countercultural spaces were often admired as hippie heavens, for some—especially for some women—these spaces had the potential to be hippie hells.

These contradictions made this countercultural space a frustrating zone for feminists. Part of the rhetoric of the counterculture was the opportunity to imagine a different world: To reject the patriarchy, and reject colonial powers, or reject heteronormative values. But, in these urban examples of counterculture, Henderson shows us that these political virtues rarely held up to scrutiny. In fact, these countercultural enclaves were sometimes much more myopic and inward looking than the media images might suggest. Sure, people protested colonialism and slavery, but when push came to shove, the Yorkville crew mobilized most effectively to reject traffic in their neighbourhood while turning a blind eye to sexual violence, or appropriating Indigenous, African American, Algerian, and Vietnamese struggles and experiences in an effort to justify their own occupation of an urban space.

Recordings are now available to watch here.

Despite these criticisms, Henderson found that there were moments of constructive change that occurred within the Yorkville scene. Vicki Taylor a singer, songwriter whose most famous song detailed her adventures on speed, called The Pill, was a woman who lived in an apartment in Yorkville. She enjoyed the freedom of the space and assumed a role of den-mother to traveling musicians. While historians recognize her gender-conforming role, or descriptions of her in motherly language, she nonetheless is also remembered for being autonomous, and an honoured conduit for bringing musicians together and providing safe accommodations.

June Callwood, a celebrated Canadian journalist, once described as “Canada’s conscience” was also connected to Yorkville. Her son was a frequent visitor to this place, and Callwood, who was already well known in the Canadian public eye, quickly recognized that curious youth were drawn to this place out of interest in something different, maybe exotic, maybe experimental. Callwood used her connections to help ensure that there were safe places for people to sleep, and to get help when needed. Many people in this subculture had complained about discrimination they faced when seeking medical care, whether for pregnancy, birth control, drug-related concerns, or venereal diseases. Callwood and others recognized that these spaces needed their own healthcare providers who could see past their long hair or tie-dyed clothing, and provide care in a non-stigmatizing way. Other health professionals began offering mobile services, through “the Trailer,” and a group of volunteers known as “The Diggers” who provided outreach, public health services, and tried to bring elements of health and harm reduction into Yorkville in ways that recognized some of the discriminatory practices that prevented people from receiving good care.

Discover Indigenous Reciprocity Initiative of the Americas

It may be tempting today to blame the hippies for what at times appears to be somewhat reckless behaviour. It is also compelling to recognize that despite some of the political claims of the New Left, much of the radicalism was still focused on improving the lives of white consumers, even reinforcing some of more traditional systems of power—patriarchy, colonialism, and heteronormativity. But, history is never that straight forward. Henderson is careful to remind us that there were moments of meaningful insight and change, and maybe these urban sub-cultures helped us to pay attention to some of the contradictions that sometimes animate our activism.

Take a minute to browse our stock:

Did you enjoy reading this article?

Please support Chacruna's work by donating to us. We are an independent organization and we offer free education and advocacy for psychedelic plant medicines. We are a team of dedicated volunteers!

Can you help Chacruna advance cultural understanding around these substances?