- Psychedelics in the Global South: Relevance and Consequences of the Countercultural Movement in Mexico - February 19, 2025

- United Nations on Psychedelics. The World Drug Report 2023 and the Renewed Interest in Psychotropics Substances - August 24, 2023

- Old Uses of Peyote in Traditional Mexican Medicine and its Inclusion in Official Pharmacopeia - July 5, 2023

There are various hypotheses about the roots of the word “marijuana,” but it´s still uncertain what it really means, and when this name appeared for the first time. However, what we do know is that this term for the cannabis plant is a contribution to the global drug culture, from Mexico to the world.

Its origins are not as racist, as has been said; the xenophobic connotation spread worldwide only after the beginning of drug prohibition. Before that, marijuana was only the word for a sacred and medical herb. But we must look further back into history on drugs.

Is it an Indigenous Name?

Now, it is clear that cannabis came to America from Europe during colonial times. But several years ago, some people believed that indigenous societies in continental America consumed marijuana since the Pre-Columbian era. The idea that Aztecs had enjoyed smoking this sacred herb spread, particularly, in Mexico.

This idea disseminated because indigenous groups that already knew about other native, natural psychoactive species had incorporated this plant in their ritual, therapeutic, and ceremonial practices. There is evidence of the use of cannabis plants by the native population since at least the eighteenth century; this later expanded to traditional and popular Mexican culture.1

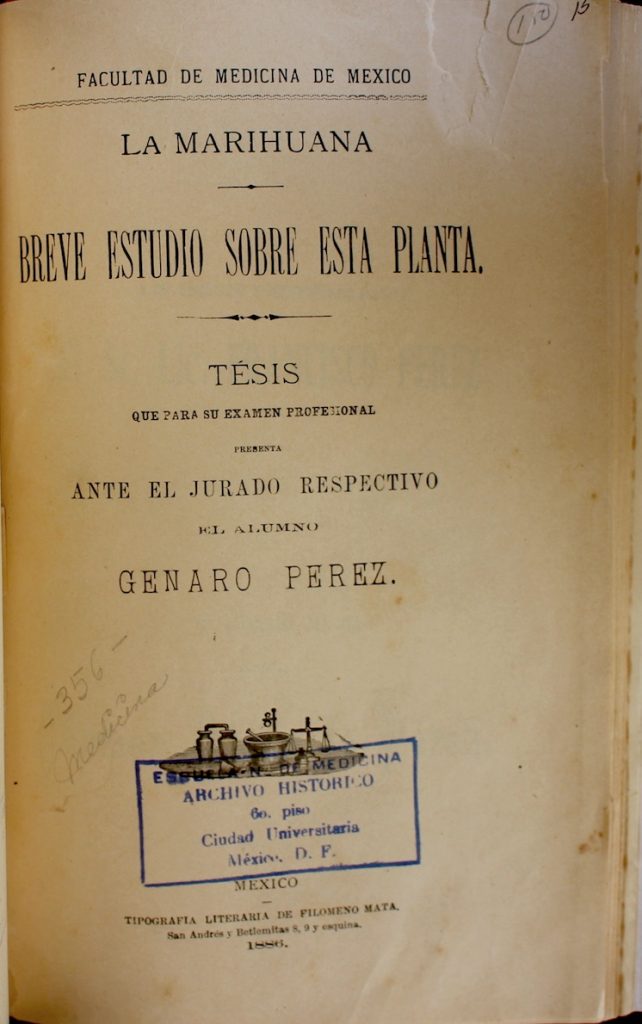

In 1846, the word “marihuana” appeared in the Mexican Pharmacopeia, an old book published by the government and containing a list of natural medicines and other drugs.2 By the end of the nineteenth century, some scientists thought that a specific kind of native cannabis grew in Mexico.3

Other scientists of the time also proposed that the word “marihuana” came from Nahuatl, one of the most important indigenous languages in Mexico. It is thought that the root of this word came from mallin, meaning “prisoner,” which related to its effects. But the real significance remains unclear.

“Stoner” Revolutionaries

Another explanation on the etymology of marijuana focused on traditional healers or herbalists who sold cannabis in street markets. These, mostly, women, were called “Marias.” This combined with the argot for the revolutionary troops, “Juanes,” resulting in the word “Mariajuana.”

Moreover, marijuana use was linked with the army, prisons, criminals, and other subaltern groups in Mexico since the nineteenth century. During the Mexican Revolution, music and other cultural expressions evoked the relationship between revolutionary fighters and weed.4 Songs like “La Cucharacha” (“The Cockroach”) referred to this “smoky” link. But by then, this herb had begun to be considered a vice and an illness, and the first restrictions and punishments would not take long to come about.

After the Revolution, the association of marijuana with indigenous people, prisoners, the underworld, revolutionary soldiers, and other popular cultures made its consumption uncomfortable for Mexican elites. Because of this association, cannabis use was viewed negatively, and considered an uncivilized act that could “degenerate the race”.5 In 1920, 17 years before the Marihuana Tax Act, the Mexican government issued a federal law that forbade cannabis crop cultivation.6

There are other theories that try to explain the origin of the term “marijuana,” including that it arose from Portuguese, Chinese or Arabic terms. But the Mexican Spanish etymology is the most deeply documented explanation. In the twentieth century, the word “marihuana,” in its Anglicized form, spread all over the world, and became the most popular term for the flowers of the cannabis plant.

(Mexican) Marijuana: Assassin of Youth

In 1937, Harry Anslinger, the famous first “drug czar,” described cannabis as “a weed of the Indian hemp family,” a “poison,” a “menace to youth,” and a narcotic “dangerous as a coiled rattlesnake”. 7

Anslinger also argued that marijuana “was introduced to the United States from Mexico, and swept across America with incredible speed.” He contributed to disseminating the idea that weed sparked insanity, criminality, murder, and violence. It´s possible the folk and Mexican term marijuana turned out to be more useful in Anslingers campaign against drugs; or, perhaps, for his racist crusade to keep immigrants back from the border.

I have heard that we should not call the cannabis plant “marijuana” because of its racist connotation. I am aware of the implied racial and historical stigma of this word; a stigma that Mexican elites, Anslinger, and other early supporters of drug prohibition contributed to spread to the world. But that is not the root of the word marijuana.

For me, especially because I am Mexican and I am a historian, the word “marijuana” implies our close relationship with cannabis flowers, with indigenous traditions, popular culture, folk medicine, and it is related to the Mexican Revolution of 1910, with the resistance to the U.S. War on Drugs, and with a new, contemporary revolution against prohibitionism.

Marijuana is a particular term that refers to the results of the final preparation for consumption, by drying the leaves and flowering tops, readying it so it can provide the amazing effects of cannabinoids on the human mind and body. It is a word for cannabis “especially, as smoked or consumed as a psychoactive drug”8 and it is another valuable contribution from Mexico to the global cannabis culture.

References

- Olvera N., & Schievenini D. (2017). Denominaciones indígenas de la marihuana en México. Relación entre el Pipiltzinztzintli y la planta de cannabis (Siglos XVI-XIX), Indigenous names of marihuana in Mexico. Relationship between the Pipiltzintzintli and the Cannabis plant (sixteenth-nineteenth centuries). Revista Cultura y Droga, 22(24), 59-77. http://200.21.104.25/culturaydroga/downloads/Culturaydroga22(24)_04.pdf ↩

- La Farmacopea Mexicana (The Mexican Pharmacopeia). (1846), México, D.F.: Academia Farmacéutica de la Capital de la República. ↩

- Pérez, G. (1886). La marihuana. Breve estudio sobre esta planta (Marijuana: A brief history of the plant) (Dissertation). Facultad de Medicina de México, Mexico. ↩

- Pérez, R. (2016). Tolerancia y prohibición. Aproximaciones a la historia social y cultural de las drogas en México 1840-1940 (Tolerance and prohibition. Approximations to the social and cultural history of drugs in Mexico 1840-1940). México: Debate, Penguin Random House. ↩

- Campos, I. (2012). Homegrown: Marijuana and the origins of Mexico´s war on drugs, Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press. ↩

- Department of Public Sanitation (1920), Dispositions on the cultivation and commerce of substances that degenerate the race, México, D.F.: Gobierno de la República. ↩

- Anslinger, H., & Ryley, C. (1937). Marijuana: Assassin of youth. American Magazine, 124, 19-20, 150-153. ↩

- Marijuana (Def.1), (2018) Oxford English Dictionary, Retrieved from https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/marijuana ↩

Take a minute to browse our stock:

Did you enjoy reading this article?

Please support Chacruna's work by donating to us. We are an independent organization and we offer free education and advocacy for psychedelic plant medicines. We are a team of dedicated volunteers!

Can you help Chacruna advance cultural understanding around these substances?