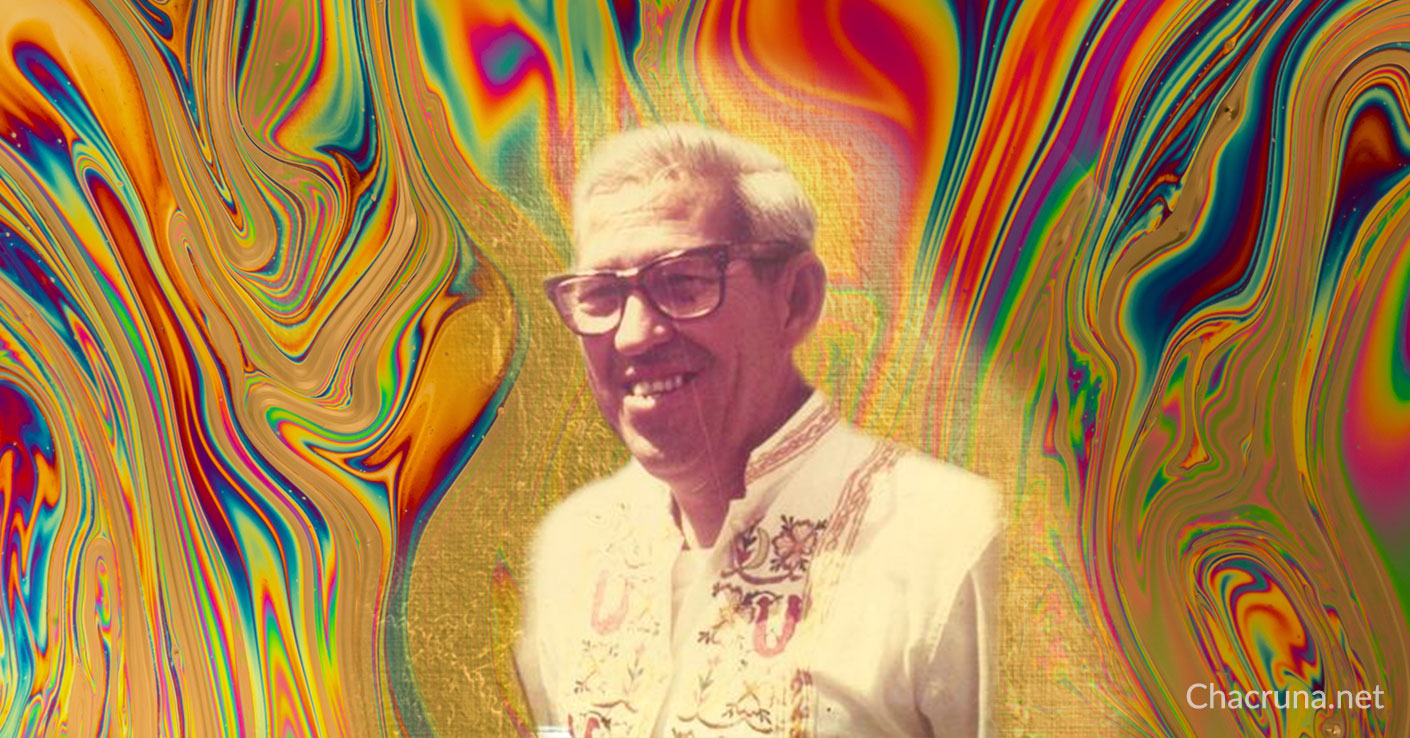

Dr. Salvador Roquet was a Mexican pioneer in psychedelic psychotherapy. He began his medical career in the field of public health and later became a psychiatrist; he started to use mind-altering substances as an adjunct to psychotherapy in 1967. His psychedelic sessions lasted about eight hours and included patients taking such substances as LSD, ketamine, psilocybin mushrooms, and ololiuqui seeds (morning glory seeds) such as Rivea corymbosa and Ipomea violacea. Salvador was widely acclaimed for developing a series of innovative therapeutic methods for using these substances. Yet, in today’s world of psychedelic psychotherapy, he is relatively unknown. Let me share some of his story with you.

In 1969, I received a letter from Salvador telling me about his work and inviting me to visit him in Mexico City. This opportunity presented itself in 1971 when I was invited to speak at the Fifth World Psychiatry Congress in Mexico City. Following the Congress, my wife and I visited Salvador; my Latina assistant served as interpreter for our discussion of his psychotherapeutic procedures.

We accepted his invitation to observe a group therapy session and were cordially received by Salvador’s patients. We chose not to ingest any mind-altering substances that evening in order to act as observers in a learning situation. As his patients began to feel the effects of the psychedelic substances, Salvador’s staff projected a violent film, “The Dirty Dozen,” on one wall of the room, and an erotic movie on the other wall. Salvador told us that his goal was to assure his patients that the expression of both their aggressive and sexual impulses was acceptable in this milieu.

There were some 20 patients seated on the carpet or cushions. Some arose and began to dance. Others cried or sobbed, turning to each other for support and consolation as they revealed intimate details about their life conflicts and traumas. Salvador moved among his patients, orchestrating their experiences and deftly forming spontaneous small groups of patients with similar issues.

Upon my return to the United States, I notified my colleagues at the Maryland Psychiatric Research Center about Salvador’s work. They immediately invited him to Baltimore where he gave a number of well-received lectures about his approach to psychotherapy. He was invited to participate in one of their “psychedelics for professionals” sessions, during which he received LSD under the staff’s supervision.

In December 1972, John Rhead, a research psychologist at the Center, wrote me, “I just put Salvador Roquet on a train for New York after his second visit here at the Center. He had a session with Bill Richards and Rich Yensen and we all had a nice visit. Thank you once again for getting us all together.” Subsequently, I discovered that the pioneering psychedelic researcher Stanislav Grof was also present during the session and that Yensen, who spoke fluent Spanish, did most of the facilitation.

In 1973, I received a letter from Salvador stating, “We are happy to have you officially on our team as Honorary Vice-President and Advisor to the Instituto de Psicosintesis.” He also sent me a long description of the Institute’s work, noting that its incorporation of psychedelic substances into psychotherapy began in 1967. The report also noted that expeditions to remote Indian villages had been organized to study the ritual use of natural psychedelic substances. From the findings of these investigators the major focus of the session emerged; namely, the indigenous peoples’ recovery of the “lost spirit.”

The report was in English, borrowing from an in-depth portrayal of the group process presented by Richard Yensen at the 1973 convention of the Association for Humanistic Psychology in Montreal, Canada. The report mirrored the activities that I had observed the previous year. To be specific: A two-hour “pre-drug” meeting begins the process, during which group members express their expectations and fears. Those who have taken part in previous sessions share their experiences, after which the group enters the treatment room. After a yoga or meditation session, one or more of the mind-altering substances are administered.

As these substances are taking effect, sensory stimulation is employed to facilitate psychotherapy. “The sensory overload show users slides, movies, three stereo sound systems, and colored floodlights which flash intermittently. The elements included in the slides and films are as varied as possible. Within what seems a confused barrage of unrelated images and sounds, there is a main theme: life. Among the themes found useful, are death, birth, sexuality, religion, and childhood. Each show is carefully assembled so that, in addition to the main theme of the evening, there are slides of particular importance for each patient. These are accompanied by music of importance to that patient.

The sensory overload portion lasts about eight or nine hours, after which portions of patents’ previous sessions may be played back to them. Patients may read statements by relevant philosophers or have these materials read to them. This is followed by a session of yoga or mediation, after which group members are allowed to sleep.

This rest period only lasts about three hours before an “integrative session” begins. Each patient discusses his or her experience, often accompanied by abreaction or catharsis. The course of therapy consists of 10 to 30 monthly sessions, although more sessions may be given to problematic patients.

In an article for the San Francisco Examiner, Barney (1977)1 observed that Salvador ran his controversial sessions for seven years, from 1967 to 1974, under an “informal agreement with the Mexican government to overlook that country’s laws against psychedelics. But then the political power shifted, and Roquet went to jail for five months.” When I found out about Salvador’s imprisonment, I wrote letters and articles on his behalf. Many other letters were forthcoming, some from distinguished physicians and psychotherapists who had never met Salvador but who admired his work. In June, 1975, Salvador wrote me that he had been released in April, expressing his gratitude for my support.

In 1977, at the annual convention of the Association for Humanistic Psychology in Berkeley, California, Salvador told Barney (1977) that political pressure evoked his release from the Mexican jail. Despite the intensity of the psychedelic experience, he claims that no patient was hurt by it. “We have 2,000 case histories and recordings of over 900 group sessions. I can say that 85 percent of them had very positive results….The 15 percent who were not helped had, at worst, ‘indifferent’ reactions. There were no cases of people failing to make the return trip to sanity.”

Taking no chances, Salvador curtailed his use of mind-altering substances in his sessions. He told Barney (1977), “After I left jail, I began to travel, giving workshops and lectures. We started doing simulated sessions, with the lights and sounds, without the drugs….We found that 90 percent of the people had reactions similar to those of people who had taken the drugs….We found that the psychedelics were nothing more than the launching pad, the nature of the sessions was conditioned by the other techniques we used.” Referring to the common themes evoked—madness, death, chaos, birth, and mystical union—he remarked, “They are all terrible—and all extraordinary. In death you can feel love, and when you feel love, death is conquered and ceases to exist.”

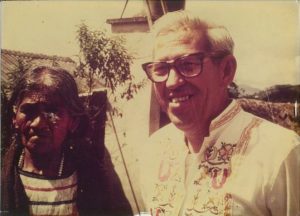

In 1980, I was invited to join Salvador on an expedition to Huatla de Jiminez to meet the legendary Mazatec shaman, María Sabina. María Sabina had been discovered by Gordon Wasson, a banker and amateur mycologist (mushroom specialist). I had read the 1957 LIFE Magazine story about their first encounter, never imagining that I would meet Doña María, some 25 years later. Roquet knew of my longtime fascination with María Sabina, with whom he had collaborated for several years; he said that this journey would be a gift from him to me. The case can be made that Wasson launched ethnopharmacology as a discipline and that María Sabina was the midwife of that birth.

Image credit: Psicología Cuántica

After a particularly hazardous drive into the Oaxaca hills, we arrived at the hamlet where María Sabina lived with her two daughters. Nicolás Echevarría, creator of the 1978 documentary María Sabina: Mujer Espiritu, had built a small house for her, affording a splendid view of the mountainous landscape. She used the house as a dressing room, donning a huipil (ceremonial gown) preceding her veladas (healing vigil), as well as for the photographs she allowed us to take during our visit.

Salvador had brought several of his patients with him, hoping that a mushroom velada would be pivotal in their ongoing psychotherapy with him. María Sabina acknowledged that the maladies of age had terminated her use of the mushrooms, but Roquet had located another local practitioner named Doña Clotilde. We located this curandera and arranged a velada for the following night.

Doña Clotilde met us at the door to her sanctuary, dressed in a huipul. Sadly, she informed us that it was the dry season and there were not enough hongitos (“the little mushrooms”) to go around. I told her that I had already experienced the mushrooms and so I would not need to take them again. Her face lit up and she said, “Well, then you can be my assistant!”

Once the hongitos began to take effect, there was the usual laughing and crying, smiling and wailing. Many people vomited; and then I realized the function of the pine boughs that had been placed inside the sanctuary. I knelt close to them and inhaled their fresh scent. This strategy allowed me to keep focusing on the revelations of the participants who were eager to share their insights with me.

The following morning, Salvador joined us. He was bright and cheerful, while the rest of us were in various stages of fatigue. Nonetheless, his patients engaged in his typical group therapy procedures. I simply went back to my hotel room and collapsed.

Image: Maria Sabina, Salvador Roquet, Stanley Krippner.

That journey was the last time I would see Salvador in Mexico. Whenever he came to San Francisco, we would get together for lunch, dinner, or a visit to the Kabuki Hot Springs, a spa which he enjoyed. I recommended that people join his non-drug “convivials” or convivencias, which he directed with considerable gusto until his death in 1995.

In 2006, I was invited to make several presentations in Zurich, Switzerland, at the centennial celebration for another dear friend, Albert Hoffman, the brilliant chemist who synthesized LSD-25. I had visited Albert and his wife Anita at their home only two years earlier. None of us had any idea that the city of Zurich would plan what turned out to be a lavish international event. I was upset that Salvador’s work was not included in the program, and so I asked Richard Yensen and one of Salvador’s assistants, Linda Rosa Corazon, to share the stage with me during one of my presentation time slots. We each mentioned Salvador and his innovative use of LSD-type drugs. There are still lessons to be learned from Salvador’s legacy and I believe history will be kind to him.

- Barney, W. (1977, September 5). Mexican therapy: “Like the end of the world.” San Francisco Examiner, p. 24. ↩

Take a minute to browse our stock:

Did you enjoy reading this article?

Please support Chacruna's work by donating to us. We are an independent organization and we offer free education and advocacy for psychedelic plant medicines. We are a team of dedicated volunteers!

Can you help Chacruna advance cultural understanding around these substances?