When Rosemary Woodruff Leary died of congestive heart failure in 2002 in Santa Cruz, she left behind photographs from her years in exile, rejection letters from various publishers, journals, newspaper clippings, court papers from various trials, and a notebook with 57 prison love letters from Timothy Leary. Her collection of fake IDs and forged passports had been destroyed many years prior. Of all the memorabilia, the most important document was her unfinished memoir, The Magician’s Daughter.

Rosemary had spent some three decades writing this manuscript by “kerosene and candlelight in Asian hotels, unheated European farmhouses, and South American jungle hut[s].” This manuscript documents her countercultural odyssey through the 1960s and the 1970s and features a candid and often unvarnished account of her tumultuous marriage with the ex-Harvard professor Leary. Although they were together for only six years (from the spring of 1965 to the fall of 1971), during those six years and after, Rosemary lived a life that seems unreal to readers today: there were three weddings to Leary (at Joshua Tree, at Berkeley by a Hindu priest, and a final one at Millbrook); Off-Broadway theatre productions; drug busts in Laredo Texas, Millbrook, and Laguna Beach; public trials and incarceration on several occasions; and an epic jailbreak from the California Men’s Colony, followed by a descent into the revolutionary underground that would take her to France, Algeria, Switzerland, Afghanistan, Canada, Colombia, Costa Rica, multiple Caribbean islands, and finally Cape Cod where she hid in broad daylight as “Sarah Woodruff” the innkeeper.

Although Rosemary lived one of the most unfathomable lives of the twentieth century, when she passed away in 2002, it looked like the memoir that documented her extraordinary life would never be published. Fortunately, due to the tireless efforts of her close friend and editor, David E. Phillips, we finally have Rosemary’s account of her own life in her own words.

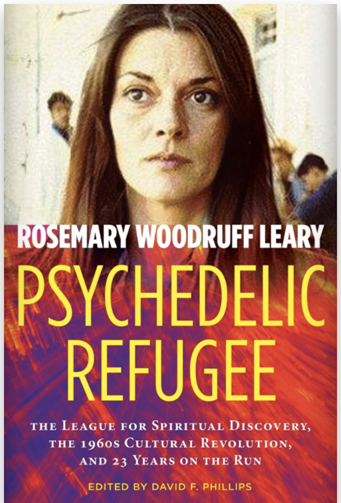

For nearly a decade, Phillips, an attorney and librarian by training, managed to resuscitate her manuscript by assembling the incomplete chapters and by locating fragments and a detailed unpublished interview with Rosemary that was conducted in 1997. Phillips’s restored version of The Magician’s Daughter was retitled Psychedelic Refugee when it was published by Park Street Press, a Vermont-based publishing house that specializes in titles that chronicle psychedelic history. Regretfully, Phillips did not live long enough to hold the published copy of Psychedelic Refugee in his hands. He passed away in March of 2020, and the book was published in March of 2021.

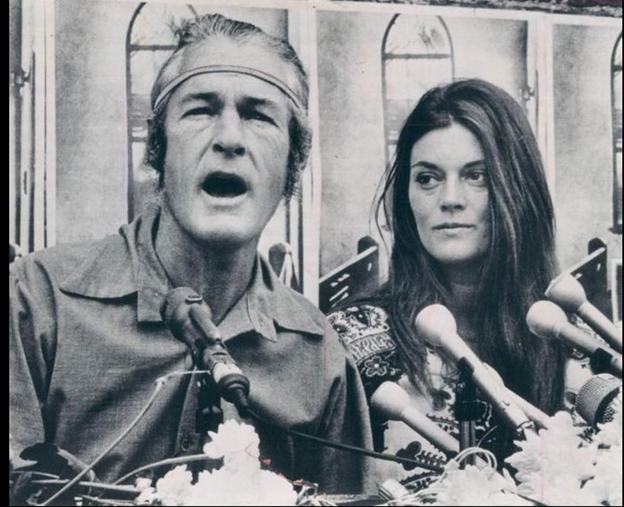

When we look at the images from the newsreels of the 1960s and early 1970s, Tim and Rosemary appear to have lived a charmed life of romance, rebellion, LSD Trips, and political activism. But another narrative lurks behind the images that appeared in the press. The book explores the highs and lows of Tim and Rosemary’s fraught relationship, and a different perspective of certain key moments in psychedelic history. The posthumous publication of Psychedelic Refugee allows Rosemary to emerge from the shadow of her famous husband. In the larger narrative of Rosemary’s life, psychedelics function as her rite of passage: they changed her life forever and ushered her down a path that she never could have anticipated. Rosemary likely never intended to be a soldier in the struggle against the War on Drugs; however, before she realized, she found herself in the trenches of the conflict. Psychedelic Refugee is a record of not only her experiences, but a life lived in extremis.

“I have regained my freedom and now can tell my story.”

Rosemary Woodruff Leary

Please donate to the Psychedelic Renaissance Documentary

At the beginning of her memoir, Rosemary writes, “I have regained my freedom and now can tell my story.” The truth is that Rosemary was never able to fully write her story because the fear of self-incrimination hung over her head like a Damoclean sword. Although she was “legally” free to write her story, she was forever burdened by the weight of the past. Rosemary was determined to protect the people who helped her when she “aided and abetted” Leary’s escape from prison in 1970, and who sheltered her during two decades of exile. That said, Psychedelic Refugee is her Sisyphean effort to reclaim her story. Although some episodes (e.g., Tim’s jailbreak) have been omitted, she left behind a powerful and moving narrative that gripped me each time I read it. In my case, the incompleteness of the tale—what some might call the lack of closure—presented a historical challenge: I had to fill in the omissions, and also figure out why these episodes had been elided in the first place.

“For Rosemary, the past is viewed as a series of powerful and magical images that resemble the lived experience of an LSD trip—surreal, humorous, unpredictable, and often absurd.”

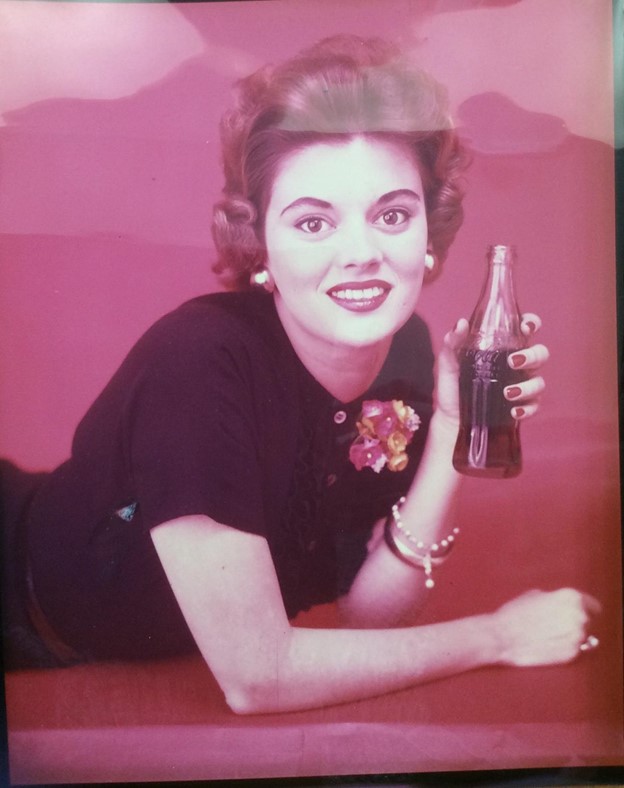

Stylistically speaking, LSD plays a central role in the narrative of Psychedelic Refugee; it influences the author’s prose style and stream of consciousness narration. For Rosemary, the past is viewed as a series of powerful and magical images that resemble the lived experience of an LSD trip—surreal, humorous, unpredictable, and often absurd. The earliest images are from her childhood. Rosemary’s story begins in a middle-class home in St. Louis in the 1950s, where she was a precocious child who enjoyed reading and performing in plays while in high school. She dreamt of leaving St. Louis and ended up engaged at 17 when Brad, an Air Force Officer, presented her with a beautiful diamond ring.

After a wedding and a honeymoon in Las Vegas, Rosemary moved to an isolated air force base in the pacific northwest. Rosemary’s new life was disappointing to say the least: “I was uncomfortable with the major’s wife and officers’ club dinners. Unwilling to learn bridge or patience. Beaten when I answered back, swore, or got angry.” Much like Stella in Tennessee Williams’s A Streetcar Named Desire, Rosemary endured domestic violence when she was pregnant. Many women in the 1950s were forced to “suck it up” and accept an abusive marriage because there didn’t seem to be any way out. However, Rosemary would not. One day when Brad was at work, Rosemary packed her clothes and caught a train bound for St. Louis. Brad returned to an empty house and found Rosemary’s discarded wedding ring in the sugar bowl.

The experience of a failed marriage pushed Rosemary in exciting new directions. She adopted the life of a seeker and the idea that life can be an adventure. After moving to New York city, she quickly immersed herself in the burgeoning jazz scene of the late 1950s and reinvented herself as an interior decorator, model, and a “beatnik stewardess” who enjoyed hosting flights to Havana and San Juan. In 1965, two events altered her life forever: she began experimenting with LSD in January and met Timothy Leary at an art gallery in New York City a few months later. Rosemary had taken LSD earlier in the day and she was transfixed by Leary’s lecture on psychedelic art and the “audio-olfactory-visual alterations of consciousness.” After the lecture, Rosemary and Leary went for a drink and the psychologist invited Rosemary to Millbrook, the enormous mansion in upstate New York where Leary lived with his associates and followers. Although Rosemary was enamored with Leary, she declined his invitation to Millbrook because she was then living with a jazz musician. A few months later, Rosemary met Leary a second time and this time she accepted his invitation.

Although Rosemary and Leary slept separately during her first night at Millbrook, she remembers feeling the professor’s presence as she slept: “I felt him through the night, footsteps pounding the maze of corridors, bare feet in the final rounds.” For Rosemary, “[Leary] was exhilarating, like the first draft of pure oxygen after a trip in the dentist’s chair,” continuing “he perceived the world with the knowledge that [his training] in psychology gave him and the unfettered imagination of an Irish hero, a combination that produced a fey charisma, a likeable madness, and an outrageous optimism… the magic of loving and being loved by such a man would keep me enthralled for many years. I could not imagine loving anyone else. Everyone was boring compared to him.”

“[Leary] was exhilarating… the magic of loving and being loved by such a man would keep me enthralled for many years. I could not imagine loving anyone else.”

Rosemary Woodruff Leary

Rosemary’s romance had several phases. First, there was the honeymoon period that lasted five months, followed by what could be described as the police harassment phase. As Leary became a popular public figure in the media, the federal government identified him as a “threat.” There were three confrontations with law enforcement ultimately resulting in Leary’s imprisonment in 1970.

The first confrontation occurred when Leary, Rosemary, and Tim’s two children, Jack and Susan were driving to Mexico. After mysteriously being turned away from the Mexican border, they were busted at the American border in Laredo, Texas. The incident put Leary back in the headlines and his legal case became a cause celebre. Before Laredo, Rosemary had no criminal record. Afterwards, she too became a target of police surveillance and harassment.

Recordings are now available to watch here.

When Leary and Rosemary returned to Millbrook in the winter of 1966, they were subjected to the infamous Millbrook raid orchestrated by G. Gordon Liddy, a Dutchess County prosecutor who was “cracking down” on drugs. Rosemary testified before a grand jury where she pled the fifth amendment (the right to not bear witness against oneself in a criminal trial) in order to not incriminate Leary and her Millbrook friends, but the judge rejected her request for immunity and she was charged with contempt of court. Rosemary served a month in jail before the charges were finally dropped because Liddy had an invalid search warrant. The full account of Rosemary’s trial and her decision not to testify are dramatized in Psychedelic Refugee. It was the first public trial in the US that examined if LSD, as a religious sacrament, could be protected by the First Amendment. The Millbrook trial was another moment in the memoir when Rosemary stuck to her principles and refused to be bullied by the judge and the prosecution.

The third and final confrontation occurred when Leary drove to a Laguna Beach suburb in 1969. He was busted for having two roaches of cannabis in his station wagon ashtray and the Orange County judge, determined to make an example out of the counterculture icon, doled out a hefty 10-year sentence. Ben Connally, a US District Judge in Texas added another 10 years to his sentence for the earlier Laredo bust in 1965. Leary now faced a 20-year sentence for possessing a small amount of cannabis on two occasions.

The third trial is a turning point in Psychedelic Refugee because Rosemary faced a key dilemma: should she let her husband remain in prison for a decade, or should she attempt to organize his escape? Rosemary and Tim’s experiences with psychedelics led them to be bold and write their own “movie”: the script they devised could be described as a psychedelic version of Bonnie and Clyde, albeit a version where the hero and heroine do not die in a hail of bullets. Would their grandiose escape plan actually work?

Part Two of “The Wonderful and Absurd Adventures of Rosemary Woodruff Leary” examines the author’s flight into European exile and her eventual breakup with the countercultural icon:

Discover the Indigenous Reciprocity Initiative of the Americas

Take a minute to browse our stock:

Did you enjoy reading this article?

Please support Chacruna's work by donating to us. We are an independent organization and we offer free education and advocacy for psychedelic plant medicines. We are a team of dedicated volunteers!

Can you help Chacruna advance cultural understanding around these substances?