- An Open Letter Reply to Dr. Stan Grof - March 28, 2025

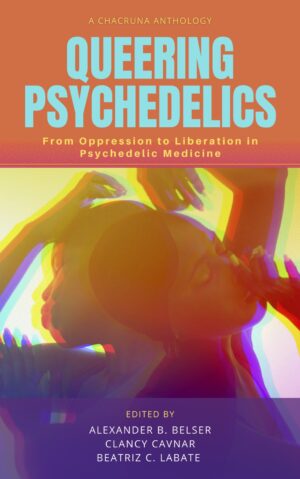

- Queering Psychedelics: An Introduction - August 7, 2024

- 10 Calls to Action: Toward an LGBTQ-Affirmative Psychedelic Therapy - October 17, 2019

- Queering Psychedelics: An Introduction - August 7, 2024

- Introduction to Women and Psychedelics - July 26, 2024

- Eight Frequently Asked Questions About Ayahuasca Globalization - February 13, 2024

- Rethinking Power, Plants, and the Future of Psychedelic Culture - May 9, 2025

- Where Is the Psychedelic Movement Headed Next? - October 15, 2024

- The FDA’s Rejection on MDMA-Assisted Therapy: What is Next for the Psychedelic Movement? - August 16, 2024

Together, we are shaping a new field at the intersections of queer and psychedelic medicine, culture, and consciousness. As the psychedelic resurgence reaches a pivotal moment of mainstream interest and regulatory legitimacy, Queering Psychedelics: From Oppression to Liberation in Psychedelic Medicine aims to foster accessibility and diversity in psychedelic science, practice, and discourse by addressing and dismantling sexist, heteronormative, transphobic, and homophobic forms of oppression in the psychedelic movement. This collected volume spans a broad range of perspectives from queer academic researchers, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex, and asexual (LGBTQIA+) clinicians, Indigenous two-spirit activists, transgender autodidacts, and queer neoshamans. Each chapter has been curated to bring to light essential insights into the lost queer psychedelic histories, the implications for current research and clinical work, and the transformative healing potential of psychedelic medicine of, by, with, and for gender- and sexually diverse peoples.

In probing a largely uncharted relationship, the authors in this book trace a vast and colorful history of the enchanted, wayward, and weird, as well as the concrete, ways that queer folk have fundamentally shaped the substance, style, and spirituality of the psychedelic movement and have been harmed by its heteronormative applications. Inclusive of the intersectional and liberatory applications of queerness, the volume integrates Indigenous outlooks on psychedelics, gender roles, and identity and seeks to ally its struggle with those of other marginalized groups: women, people of color, the disabled, the poor, and people residing in the Global South.

The book also grapples with how modern psychedelic research might address the unique needs and traumas of sexual and gender minorities—populations that can suffer from challenging mental health conditions brought on by social exclusion, pathologization, criminalization, and stigmatization. Queering Psychedelics interrogates the continuing radical potential of queer psychedelia in today’s era of assimilation and increasingly codified and discursively managed identities, paving the way for the movement’s liberatory potential for all people.

Queering Psychedelics interrogates the continuing radical potential of queer psychedelia in today’s era of assimilation and increasingly codified and discursively managed identities, paving the way for the movement’s liberatory potential for all people.

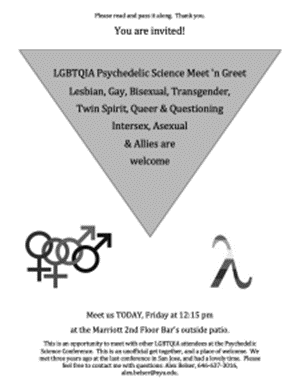

The book is a first-of-its-kind in many ways. The field has grown large enough to warrant the emergence of this book into the world. To illustrate, here is a short history of queerness at psychedelic conferences over the last 20 years. In 2001, one of our authors, Alex Belser, attended his first-ever psychedelic conference at the Berkeley International House. Although there were many fascinating talks, there was no mention of the word “gay.” It was a colorful, but largely straight, affair. In 2004, the next Mind States psychedelic conference was held in Oaxaca, Mexico. There, a handful of queer folks gathered unofficially in a hotel room to laugh and reflect on their queerness and psychedelic experiences. In 2010, the first Psychedelic Science conference was held in San Jose. The psychedelic conference scene was bigger now, and there were calls for presenters to “wear ties” to be taken seriously. Among rows of chairs in the conference hall, Belser and Clancy Cavnar recruited some conspirators to hand out flyers illustrated with an inverted pink triangle and a rainbow lambda, announcing the first “LGBTQIA Psychedelic Science Meet ’n Greet.” About 20 of us met in the garden for a circle of intimate introductions. One couple who met there are still together a decade later! Three years later, in 2013, we gathered the queer folks again at Psychedelic Science 2013 in Oakland. Our group had grown to 40 people. At the next Psychedelic Science conference in 2017, we filled a conference room to brimming with over 80 people, all curious, alive with ideas, and hoping to find queer community in the psychedelic space.

In 2019, the Chacruna Institute, including the three coeditors of this book, hosted an event that was in many ways inaugural and brought those “small meetings happening in the basement” to the main stage: Queering Psychedelics, the first-ever conference highlighting queer visionaries in the psychedelic community, at the Brava Theater Center in San Francisco, held during Pride month. A huge crowd of around 400 people attended, and it sparked something beautiful. Queering Psychedelics 2019 was the first conference examining the history of psychedelics from queer and nonbinary perspectives. Over two days, there were 13 keynote speakers, three intimate breakout sessions with conference attendees, and one final panel, all before a rainbow audience. In the midst of skyrocketing interest in psychedelic research, the conference was motivated, in part, to ensure that traditionally underrepresented communities share a seat at the table and have their voices heard so as to ensure access to all the benefits that psychedelics and plant medicine offer. We also believed it was vital that queer spaces be established for exploring the unique needs, gifts, and strengths that LGBTQIA+ communities bring to psychedelics and psychedelic medicine. Two years later, in 2021, we hosted Building Bridges: Queering Psychedelics Two Years Later, rounding out two decades of psychedelic conferencing culture.

With this book, we aim to gather together leaders in the space to help construct a new queer vision for the psychedelic future. We ask you, the reader, to unite with us and build bridges to the future we can envision together—a future where we address and dismantle sexist, heteronormative, transphobic, and homophobic forms of oppression in the psychedelic movement. In this volume, you’ll read about queer psychedelic phenomenologies, the uncovered history of psychedelic conversion therapy, the hard work of self-acceptance through psychedelic practices, and also the unique gifts of queer pleasure, mysticism, and magic. We discuss race, intersectionality, and psychedelics as liberatory tools for LGBTQIA+ folks, and center transgender and gender-diverse psychedelic experience. In a multiplicity of voices, the authors interrogate the continuing radical potential of queer psychedelia and create a space to move from oppression to collective liberation. We invite you to join us.

QUEER TERMINOLOGIES

Before we provide an overview of the chapters of this book, we’d like to share a few words on words. Throughout this book, different authors use different terms. These include two-spirit, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex, and asexual (2SLGBTQIA+), LGBTQIA+, LGBTQ, sexual and gender minority (SGM) people, sexual- and gender-diverse (SGD) people, and queer folks and folx. Each group within this umbrella has its own important lineages, manifestations, and contributions. As editors of Queering Psychedelics, we did not mandate a standard terminology. Regarding the title itself, we appreciated the commentary by one of our author contributors, Diana Quinn, who writes, “Although the term ‘queer’ is not universally accepted by members of the 2SLGBTQIA+ community, its use here as a shorthand to refer to SGM is intended in the spirit of reclaiming ‘queer’ from its historical use as a denigrating slur toward a representation of the radical and subversive overturning of limiting, cis-heteronormative societal mores.”

“Although the term ‘queer’ is not universally accepted by members of the 2SLGBTQIA+ community, its use here as a shorthand to refer to SGM is intended in the spirit of reclaiming ‘queer’ from its historical use as a denigrating slur toward a representation of the radical and subversive overturning of limiting, cis-heteronormative societal mores.”

Diana Quinn

HOW TO READ THIS BOOK

The book is written by 42 authors in 35 chapters and structured into 9 sections spanning diverse topics. The book can be read in sequence, but feel free to hop around and read what is of interest to you. The sections of the book are as follows: (1) From Oppression to Liberation: Organizing for Change; (2) Psychedelic Conversion Therapy; (3) Queering the Clinic: Psychedelic Treatment: (4) Transgender and Gender-Diverse Psychedelic Experience; (5) Race, Intersectionality, and Psychedelics as Liberatory Tools for LGBTQIA+ Folks; (6) Psychedelics and LGBTQIA+ Self-Acceptance; (7) Ayahuasca, Santo Daime, and Queer Psychedelic Spirituality; (8) Sexuality, Psychedelics, and Queer Pleasure; and (9) Expansive Queer Psychedelic Phenomenology.

FROM OPPRESSION TO LIBERATION: ORGANIZING FOR CHANGE

Queering Psychedelics opens with five chapters in a section dedicated to the movement from oppression to liberation. In the first chapter, Ava Keating and Alex Belser reckon with the rediscovered histories of oppression of LGBTQIA+ in psychedelic research. They offer “a queer vision for psychedelic research” in which we leverage our collective power to reform current dominant paradigms in psychedelic research and “coconstruct transformative visions for liberatory psychedelic research for all.”

In the next chapter, a collaboration between Amy Bartlett, Challian Christ, Stéphanie Manoni-Millar, and Terence H. W. Ching, the authors conceive of psychedelic research as a form of storytelling. They decry the old narrative as queer erasure and begin to tell a new story, raising a call to action for both straight and queer researchers that is nuanced and powerful. We would do well to heed their call.

In the next chapter, Ariel Vegosen provides a queer response to psychedelic privilege and shares her work to found Queerdome, which provides “queer-centered psychedelic harm reduction through a physical, emotional, and spiritual safe haven” at events large and small. While we often hear idealizing rhetoric that psychedelics can “help end oppression and create unity on planet Earth,” Vegosen argues that “psychedelics on their own will not create healing or a better world; they work only if people are prepared to do the work of integration . . . If we want psychedelics to be the healing antidote, we also need to do the work of justice so that, after therapy, ritual, or a recreational journey, we have a safer world to return to.”

In a transcribed conversation that is “an act of decolonizing and queering the academic space,” Courtney Watson and Emma Knighton reflect on and problematize certain tropes in the psychedelic space as guises for cisheterosexual privilege. They deconstruct the idea that psychedelics “allow” people to transcend race, gender, and sexual identity as motivated by a “we’re all one” narrative that perpetuates systems of oppression. This “transcendence” narrative is itself a type of dominant erasure that is possibly motivated by fragility and guilt around holding privilege.

Lastly, in this opening section, Diana Quinn describes community care as the heart of queer psychedelic liberation. In advocating for group work and queer community psychedelic spaces, she writes eloquently of their potential. She cites trauma-responsive and liberation-centered psychologist Kulkiran Nakai who says, “Queer psychedelic spaces can embolden a community of care to help repair and rewire the rejection, abandonment, and isolation experienced by many of us queer folx who may have grown up in oppressive homes guided by the colonial context of sexism, heteronormativity, homophobia, and transphobia. In order to dismantle these injected systems of oppression, community care in queer psychedelic spaces can help heal and transform ourselves towards individual and collective liberation.”

Discover the Indigenous Reciprocity Initiative of the Americas

PSYCHEDELIC CONVERSION THERAPY

In this second section of the book, we uncover the history of how psychedelics like LSD and mescaline were used coercively against LGBTQIA+ people by their doctors, clinicians, and psychedelic researchers to “convert” them to heterosexuality. Conversion therapy, now universally condemned by professional organizations and outlawed in many states, was a mainstay of psychedelic treatment. This abusive practice was promoted by influential people in the psychedelic community such as Timothy Leary, Robert Masters, and Jean Houston.

In original scholarship by Andrea Ens, she reports on the use of psychedelic conversion therapy at Hollywood Hospital and by leaders in the psychedelic clinical community, including Richard Alpert (Ram Dass) and Stanislov Grof. She writes how psychedelics have “been historically used in harmful attempts to eradicate so-called sexual deviancy” and to reinforce anti-gay social doctrines. Looking to the root factors that led to the development of psychedelic conversion therapy, Ens argues that the “conflation of homosexuality and Communism, rising faith in chemical interventions to solve psychiatric problems, and the increased importance of psychoanalysis during the postwar period created the necessary context for psychedelic conversion therapy” to become an ascendant clinical practice.

Continuing in this vein, Tal Davidson provides an important contribution that succinctly articulates the psychoanalytic rationale for psychedelic conversion therapy. Davidson asks, “What was that particular confluence of systemic heteronormativity, virulent public homophobia, and internalized homophobia that made drugs known for freedom work like drugs of suppression?” In a synthesis of clinical accounts from British, Greek, and American psychotherapists in the 1950s and 1960s, we are shown how clinicians thought about how gay people “became heterosexually orientated” with LSD treatment, which was thought powerful enough to override the patient’s defenses.

Lastly, in a truly critical piece of scholarship, Zoë Dubus dug into the French annals to unearth the harrowing clinical cases of two adolescents, Michel, age 15, and Bernard, age 18, described as “delinquent sex perverts.” They were subjected to psychedelic “shock therapy,” one of a class of therapies that included electroconvulsive therapy, lobotomy, and insulin coma therapy. These shock therapies “aimed at dismantling mental and cognitive structures and rebuilding them with the aid of psychiatric treatment.” Michel and Bernard were subjected to repeated sessions during which doctors injected them with extraordinarily high doses of psychedelics (up to 1,200 mg of mescaline and 800 mcg of LSD, or approximately 8 standard hits of LSD in a single dose). At one point, Michel asks: “what is this violence for?” The transcriptions of these sessions show their anguish and their incomprehension from these abusive treatments.

Anyone reading these case accounts must acknowledge how horrifying and enraging these practices were. Unfortunately, the vast majority of the psychedelic clinical community today continues to be blithely ignorant of its own history. After decades of forgotten abuse, we must not once again bury these stories, but rather bring to light the ways that psychedelic medicine was used for coercive and violent ends by people in positions of power.

QUEERING THE CLINIC: PSYCHEDELIC TREATMENT

In this section, entitled “Queering the Clinic,” we present a half-dozen contemporary accounts reenvisioning how the clinic can be a place of queer healing and innovative practices. In his description of queer rejection and isolation, Matthew D. Skinta outlines how psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy could serve as a salve for minority stress. Weaving in a touching personal account, Skinta’s writing inspires hope that affirming psychedelic therapy might hold promise for queer and trans people affected by minority stress and its ills.

Next, in a fascinating in-depth case presentation, Chris Stauffer and Andrea Rosati illustrate how we might queer MDMA-assisted psychotherapy. We (Belser) have worked with gender and sexual minority participants in MDMA treatment, and it is wonderful to see the authors attend to the vivid psychedelic experiences of the participant with such attunement. The chapter is remarkable in that it is the first published queer case study in a legal psychedelic clinical trial.

In his trenchant account of treating men at one of the country’s largest LGBTQ+ health centers, John Haupert describes feeling powerless as he watched “vibrant gay men in their prime deteriorate into chronic meth-induced psychosis within less than a year.” In a stirring and refreshing approach, Haupert shares how he “threw out the rule book” and used everything but the kitchen sink as part of a comprehensive and innovative harm reduction approach to help gay men quit crystal meth. He even proposes prescribing psychedelics such as 2C-B as a “safer alternative” and “an ideal choice for a chemsex replacement” that would be far less harmful than meth, which has resulted in a litany of harms to individuals and the community. His chapter reorients psychedelics as harm reduction and connects the dots to psychedelics as queer connectors in the “deficient domain of meth treatment.”

The next three chapters in this section round out models for shaping and forming a queer clinic in our times. In their chapter “The Quest for Queer Liberation: Ketamine-Assisted Psychotherapy and Shame,” Shanna Butler and Laura Mae Northrup are among the first to provide a rationale for ketamine-assisted psychotherapy (KAP) to treat minority stress and the resulting shame. They write, “shame results in limits to self expression, policing of desire, invisibilizing identities, and even the urge toward self-annihilation.” Through the introduction of a clinical case, they argue that KAP is “uniquely situated to address shame incurred from internalized homophobia and transphobia through both its physiological and transpersonal effects” and describe “KAP’s potential for decreasing shame and increasing access to liberatory states of being.”

In Jeanna Eichenbaum’s contribution, she asks the reader to “widen the lens” of the conventional ideas of set and setting. What if set included one’s sexual and gender identity? Moreso, what if we expanded “our view of what constitutes ‘set’ in clinical practice to include the journeyer’s positionality within their community and the larger society” as a means “to serve our clients more fully in psychedelic healing work.” What if the psychedelic setting were conceived more expansively, “to include aspects of the social and cultural environment that the experience exists within,” including racism, misogyny, homo/bi/transphobia, late capitalism, and the existential threat of the Anthropocene and global ecocide? Eichenbaum argues that, paradoxically, an awareness of these levels of setting may foster “a renewed sense of commitment and alliance with the natural world” and enable the “deeper potentials of the work.”

Finally, Scott McKernan and Alex Belser offer a pragmatic, nuts-and-bolts step that psychedelic researchers can take to make their practices more affirming. The authors describe the ways that current psychedelic clinical trials often propagate harmful practices, including not asking for pronouns and preferred names, not assessing gender and sexual identity, and failing to run and publish subgroup analyses. Without these data, it’s impossible to determine if psychedelic treatments work as well for sexual and gender minority people as for their heterosexual peers. To address these challenges, they propose a uniform assessment of sexual orientation and gender identity in psychedelic clinical trials as a step toward addressing the treatment needs for this underserved population. This list of items offers a standard questionnaire that could be disseminated in clinical trials and serve as a basis for meta-analysis of clinical data across trials to determine how queer folks fare in psychedelic treatments. The chapter provides a frame for emerging best practices for assessing sexual orientation and gender identity in psychedelic clinical trials.

TRANSGENDER AND GENDER-DIVERSE PSYCHEDELIC EXPERIENCE

In the opening chapter to this section, Sam Claude Carmel titles the piece, “Transcending Dysphoria: Exploring the Novel Counter-Dysphoric and Lifesaving Effects of Psychedelics in the Transgender Community.” Through interviews with trans participants exploring clinical and underground psychedelic usage, this chapter highlights the novel counter-dysphoric effects psychedelics have for many trans people and their ability to aid gender identity self-acceptance, alleviate depression, and avert suicide for trans and gender diverse folks. Carmel calls for affirming practices, stating, “To achieve our collective goal of psychedelic equity, the development of new modalities of trans-affirming psychedelic integration therapy and harm reduction are necessary alongside expanded access to psychedelics in clinical and research contexts for transgender people.”

In Taylor Dahlia Bolinger’s chapter, “Gender Rituals and Gendered Ritual,” she advances some timely ideas about decolonizing gender and the special role queer folks may play as ritual specialists in psychedelic spaces. Drawing in part from her own experiences, she reflects that, due to internalized gender schemes that evoke wariness, “To be trans in psychedelic spaces is often to be radically alone.” She argues that “[t]ransition-as-a-ritual requires performances for doctors and other gatekeepers that require many of the elements of ritual described previously, and that may not even resemble the gender-diverse person’s lived experience of gender . . . The psychedelic community must transcend the colonized gender binary if we intend to face the deeper traumas of our society”

In the next chapter, a queer and trans/nonbinary patient who goes by “PatientNB” shares their perspective as a patient in psychedelic therapy. In clear prose, PatientNB writes how they have intentionally used psilocybin with “intense therapy work” to come out as trans to family and friends, despite experiences of parental rejection, discrimination, stigma, and shame. They write, “Looking back on that first experience with psilocybin, I can see now that the freedom I felt came from finally realizing that there was nothing wrong with me. It was not me who was fucked up, but the world that was fucked up.” This chapter is perhaps the first published account by a trans or non-binary person’s experience in a gender-affirming psychedelic integration psychotherapy. They conclude, “I was finally able to see how that little trans kid was perfect exactly as they were. As they are.”

As the last chapter in this section, Tristan Angieri writes about the representations of the queer and trans communities in storytelling and film, or lack thereof. Working from their own experience suffering from severe PTSD for over 15 years and then receiving MDMA-assisted therapy, Angieri shares how they “have shifted away from a place of egoic definition by my queerness and transness into a place of unconditional love and embracing of my queerness and transness.” This chapter servers as a companion piece to a short documentary film, Integrate.Me, in which they depict their own “lived experience outside of the gender binary” in service to the stated mission: “to advocate for entheogenic therapy, harm reduction, and drug policy reform as transformative tools for communal healing by connecting them to my own personally vulnerable story.”

RACE, INTERSECTIONALITY, AND PSYCHEDELICS AS LIBERATORY TOOLS FOR LGBTQIA+ FOLKS

In a thoughtful reflection on intersectional issues in psychedelic practice, Terence H. W. Ching writes about his experience of MDMA-assisted psychotherapy as a gay Singaporean Chinese male. Citing the “limited minoritized enrollment” in MDMA clinical trials to date, Ching advocates for “An explicit, study-wide, culturally attuned recruitment plan to oversample historically excluded groups” so as to meaningfully diversify recruitment. Sharing the nuances of his own experience as an immigrant “coming out” in the context of prescribed Western norms, Ching argues for an acceptance of intersectionality and that “considerations of intersectionality will shift towards the forefront of researchers’ minds as they recruit, enroll, and sit with people as they embark on their psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy journeys.”

Kaston D. Anderson-Carpenter examines the role of psychedelic medicine in the context of African spirituality to support healing for Black queer individuals. In a concise but detailed history, Anderson-Carpenter debunks the notion that African diasporic spirituality is anti-queer. He shares how datura, iboga, and a psychedelic plant named kwashi have been used by the Shangana-Tsonga, Bwiti, and Bushmen people, respectively. Today, acknowledging the context of intersectional traumas faced by Black queer people, Anderson-Carpenter concludes, in part, by stating, “Psychedelics can open pathways for Black queer individuals to commune with and receive guidance from their ancestors, the spirits, lwa, and/or orishas. This communication can also provide greater clarity to one’s own experiences of psychological and physical trauma.”

“Psychedelics can open pathways for Black queer individuals to commune with and receive guidance from their ancestors, the spirits, lwa, and/or orishas. This communication can also provide greater clarity to one’s own experiences of psychological and physical trauma.”

Kaston Anderson

Finally in this section, Behike Sensei Kevon Simpson describes high dose psilocybin healing work with urban medicine people and BIPOC folks. He presents excerpts from interviews with six people that are incredibly beautiful, and advocates for a new higher dose standard of psilocybin within a harm reduction frame. As one participant, Kendra Valentine said, “I was reminded that I am both a child of and a mother to this beautiful earth that I am blessed to walk upon. I was shown my own magnificence, in its entirety, and learned how to love all parts of me more inclusively.”

In the opening chapter to this section, Kate Kincaid presents stories of women and gender and sexual minorities finding strength and empowerment through nonordinary states of consciousness. Through her own psychedelic work, she “learned that it’s okay to take up space” and traced “this fear of taking up too much space or being too loud as a vestige of gendered conditioning.” Kincaid shares stories from people who have changed through psychedelic conscious experience; a queer friend taking a large dose of psilocybin said that they “could see all of their different gender identities moving fluidly on their face and body. It was after this experience that they felt emboldened to claim their nonbinary gender identity and start using they/them pronouns.” Kincaid claims, “Queer people who use psychedelics know the psychedelic worldview is inherently queer.”

In the second chapter of this section on psychedelics and self-acceptance, Valentin Somma playfully asks, “Can Psychedelics Queer You Up?” Drawing from his own experience and observations, he writes about how experiences with psychedelics can mitigate internalized homophobia in “mostly straight” and “straight passing” folks. Somma says, “Building on my own anecdotal experience, I’ll show how psychedelics may encourage more exploration and self-acceptance for the fringe of individuals whose sexuality easily passes as heterosexual to others or to themselves. That includes many, like me, who might not have known they could get curious about queerness.”

In Justin Natoli’s clear-seeing and stout-hearted look at polyamory through the lens of psychedelic practice, he shows that “every encounter with another person, however fleeting, can be a sacred relationship if we allow it.” Natoli shares powerful first-person accounts of how psychedelics helped people recover from internalized shame, trauma, and the socially constructed dominance of monogamy. For example, they describe how psychedelic experience has helped “anxiously-attached people become more secure in polyamory,” drawing from personal and professional accounts.

AYAHUASCA, SANTO DAIME, AND QUEER PSYCHEDELIC SPIRITUALITY

Marca Cassity and Katherine A. Costello’s collaboration begins with Cassity’s gripping story of their experience, as a two-spirit person of a Santo Daime ritual with ayahuasca. In Costello’s response, she is in dialog with Cassity’s story and presents thoughts on structural change and how White settlers can help decolonize gender and sexuality. As coauthors, they intend to “model a kind of dialogue—between a 2S person (a Native American person who is also LGBTQIA+) and a White cis queer ally, between narrative and theory—which we believe necessary for decolonizing, queering, and ‘trans-ing’ psychedelic spaces.”

In her contribution, Clancy Cavnar provides a sweeping reflection on spirituality, gender, and power in her experiences in the Santo Daime church over the past 25 years. She describes the complexities of participating as a church member in the context of different forms of homophobic and sex-segregating treatment. She also traces a sexual scandal and the movements of power within the church. In her nuanced treatment of her relationship to the church, Cavnar shares poignantly how “the rituals and customs carved a particular place in my heart.” She concludes by encouraging reform even if it “may take some generations before this is a reality in the church of Santo Daime.”

In Beatriz C. Labate’s insightful interview with the Brazilian sociologist Pietro Benedito, Benedito draws on his dissertation research regarding women within Santo Daime to critique cis-heteronormativity within church practices and the characterization of homosexuality as degenerate or promiscuous. As a transmasculine sociologist, Benedito describes how he has not visited a Santo Daime church since his transition. Although he wants to return, “I don’t believe this will be an easy task, as transphobia in religious spaces is a reality, and Santo Daime has this important setting that divides women and men spatially,” concluding, “Trans people should have the freedom to choose where they feel more comfortable.”

In Zach Levine’s rollicking exploration into the parallels between ayahuasca lightwork and queer sex and sexuality, he explores the deeper and darker homophobia in many ayahuasca circles. He explains “why it matters if you drink it with people who say or believe that your sexuality is not natural.” In meaningful discourse, Levine argues that “ayahuasca has something to say about sex,” and in his chapter, writes on the human sexuality, desire, and social restrictions in the context of ayahuasca ceremony.

SEXUALITY, PSYCHEDELICS, AND QUEER PLEASURE

In their compelling article “Reclaiming Ecstasy,” Dee Dee Goldpaugh argues that “the notion that psychedelics exist to assist us in being more adaptable under capitalism in a heteropatriarchal society is a narrow and incomplete story.” Instead, they advocate for “a queerer story,” in which psychedelics can engender experiences “of ecstasy, of erotic embodiment, and of joy.” Goldpaugh articulates “a vision for queer psychedelic healing” that encompasses community-held spaces for healing, includes play, communal music-making, and storytelling, allows for shapeshifting identities and creating new ritual forms, and reclaims erotic energy and the power of pleasure in psychedelic healing.

In her thought-provoking exploration of an expanded view of queer psychedelic erotics, Alex Dymock interviews participants and finds a number of erotic encounters with objects, materials, and technologies that are nonhuman or inhuman. Utilizing perspectives of new materialisms and posthumanisms, Dymock observes that “the majority of research on sex and drugs tends to focus on substances typically associated with sexual enhancement (such as GHB/GBL, Viagra, and mephedrone).” Instead, she finds evidence for how psychedelics can enhance erotic connectedness principally with other objects, materials, and technologies.

In the final chapter in this section, Denise Renye suggests that the psychedelic communities and the kink communities can learn from one another to the benefit of queer folks. In comparing aspects of bondage/ discipline, dominance/submission, and sadism/masochism (BDSM) and psychedelic containers, Renye finds parallels for set and setting, safety, embodiment, the healing of trauma, the possibilities of transformation, and exploration of the psyche. She argues that both “offer a transcendent edge; the psychedelic, via the self, the plant or substance, and the facilitator, together in the setting; the kink scene, via the self with another and the field they cocreate. The play itself and the connection between (or among) the partners is the medicine.”

Shop our Collection of Psychedelic T-Shirts.

EXPANSIVE QUEER PSYCHEDELIC PHENOMENOLOGY

In the chapter by the irReverent joie wolfw’mn, the author provides a secret history of large-scale radical queer pagan psychedelic rituals in the United States during the AIDS crisis and in the decades since. These “homocentric” events centered around Beltaine, an annual holiday marking the first day of summer in the Celtic and pre-Christian western European traditions, during which hundreds of queer people consumed mushrooms together after dancing around the Maypole. To our knowledge, this large-scale psychedelic ritual practice has largely gone unrecorded until now.

In the penultimate chapter of this section, we receive an invitation to mythopoesis (mythmaking) from Kile M. Ortigo and Daan Keiman. Acknowledging the “collective crisis in meaning,” they draw from the work of Joseph Campbell, Maureen Murdock, and others to generate new queer-inclusive mythologies for psychedelic integration. “Whereas queer experiences may have been largely (but not entirely) missing in previously dominant mythologies, we can revise, as well as manifest, entirely new stories to fit the grand unfolding narrative of our human adventure.”

In her expansive conclusion titled “The Psychonaut, the Rapist, and the Rainbow,” Ayesha Hussain begins with a simple question: “What does queer liberation truly mean?” Using a lively reinterpretation of the first book of The Chronicles of Narnia as an expanded allegory of queer liberation, Hussain says that, to get to Narnia, “Queerness needs an awakening.” She suggests each and every queer finds a way “to experience a psychedelic sexual awakening” and envisions a future where “everyone is polyamorous and pansexual.” She closes by inviting us to give up the “same tactics of imperialism, colonization, separation, and capitalism” that are often used to ostracize each other and instead join her, sitting “on the throne as queer royalty” in a world “of free love, free expression, and free exploration.”

Note: This article was originally published as the Introduction to Queering Psychedelics: From Oppression to Liberation in Psychedelic Medicine (Synergetic Press, 2022).

Art by Mariom Luna.

Take a minute to browse our stock:

Did you enjoy reading this article?

Please support Chacruna's work by donating to us. We are an independent organization and we offer free education and advocacy for psychedelic plant medicines. We are a team of dedicated volunteers!

Can you help Chacruna advance cultural understanding around these substances?