- Psychedelic Saskatchewan: Kay Parley - April 14, 2021

To anyone and everyone

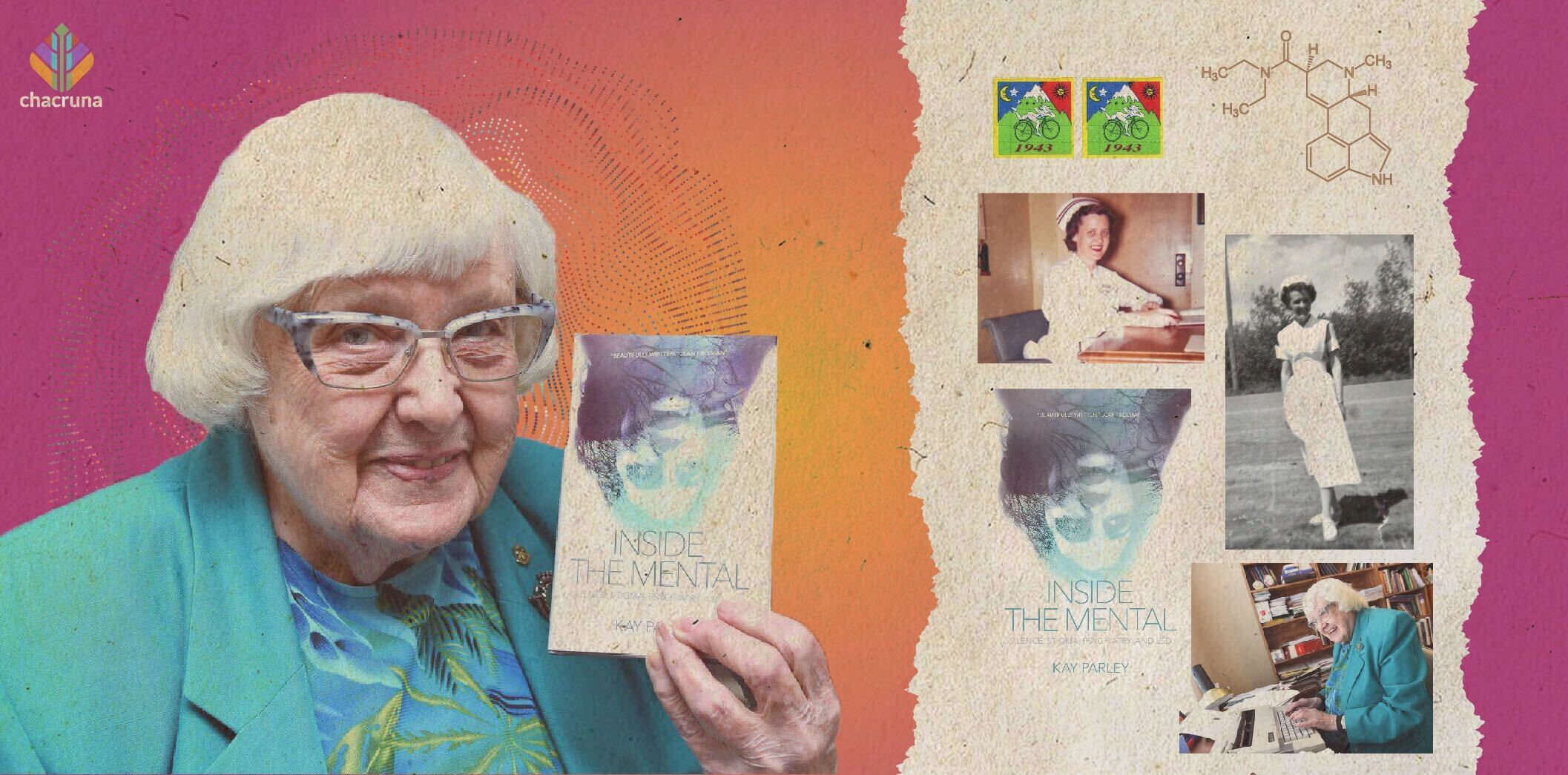

who fights the stigma

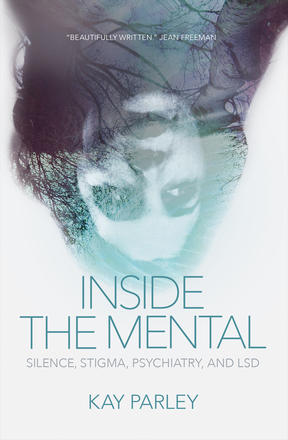

This is the simple, heartfelt dedication that greets readers of Kay Parley’s remarkable 2016 memoir Inside the Mental: Silence, Stigma, Psychiatry, and LSD. The dedication reflects Parley’s ethos throughout: the book feels like a beguiling conversation with a compassionate, straight-shooting friend who happens to have a razor-sharp memory and a treasure trove of stories. To say that Kay Parley (who turned 98 this year) has lived a remarkable life would be a laughable understatement.

All in the Family

Born in 1924 and raised on a farm in southeastern Saskatchewan, Canada, Parley grew up having never met her maternal grandfather, who was institutionalized in the nearby Weyburn mental hospital with a diagnosis of paranoia. When she was six, her father, diagnosed with manic-depressive psychosis, was committed to Weyburn too.

A recent graduate of Lorne Greene’s Academy of Radio Arts, in 1948, Parley was an aspiring actress and working as a secretary at CBC radio headquarters in Toronto. She was 25. That’s when she began to hear voices. The voices would natter on about prophecies or command that she walk across the city and back until her feet bled.

Her symptoms worsened until she had her first full-on breakdown. Her mother flew out, brought her home and delivered her to Weyburn too. It would take until 1972 (and four more breakdowns, which arrived precisely every six years) for her to be diagnosed with manic-depressive psychosis (MDP).

Though it felt like the end of the world, Parley’s entrance into “The Mental” (as locals called it) was the beginning of a life-changing journey that saw her transform from a frightened young patient into a psychiatric nurse, teacher, artist, freelance writer, memoirist, and novelist.

Discover Indigenous Reciprocity Initiative of the Americas

Kay Parley: From Patient to Nurse

Weyburn Mental Hospital sowed the seeds of Kay’s rebirth and healing. During her nine-month stay, she started painting again; she met her grandfather for the first time; she reunited with her father; she even edited the hospital newspaper, The Torch. After a few years bouncing around various secretarial jobs and between Regina and Toronto (where she had another breakdown), a letter from a friend informed her that a new superintendent had taken over at Weyburn and was making improvements. She was intrigued and felt something pulling her back. The letter felt like a sign. “It began to look as if I was destined to be involved with psychiatry,” she writes.

Parley returned to Weyburn in 1956 as a trainee psychiatric nurse, a burgeoning profession at the time, and set out, as she puts it, to “learn something concrete about mental illness, to find a new and worthwhile interest in trying to help those who were sick like me.” By then, British psychiatrist Humphry Osmond had overseen the (newly renamed) Saskatchewan Hospital at Weyburn for five years and radical change was in the air.

Join us at Sacred Plants in the Americas II

Osmond had joined forces with biochemist and psychiatrist Dr. Abram Hoffer (both believed that the cause of mental illness was biochemical, a relatively new theory) and the two were well advanced in their groundbreaking LSD trials aimed at understanding and treating schizophrenia, psychosis, and alcoholism. Osmond is famous for having coined the term “psychedelic,” in a letter to his good friend, author, and fellow Englishman Aldous Huxley (by then living in California) in 1956.

Dr. Osmond had introduced Huxley to mescaline three years prior, prompting Huxley to write The Doors of Perception. In the journal she kept from this time, Parley writes, “I admire Dr. Osmond so much. He is so bubbly and interesting and kind, and so concerned with treating the mentally ill like deserving human beings.”

Into the early sixties Parley became known among her colleagues as an excellent “sitter,” tirelessly guiding patients through their all-day LSD therapy sessions with utmost care, dedication, patience, and understanding. In an essay she wrote for the American Journal of Nursing in 1964, she explained why she and her colleagues derived so much satisfaction from working these sessions.

“The psychiatric nurse appreciates a situation that provides an opportunity for her to form constructive personal relationships with her patients. She likes to be involved in treatments that give her patients the most benefit with the least mental or physical discomfort, and she enjoys seeing results from her work. Anyone who has watched LSD properly used knows LSD is rewarding in all these areas.”

Kay Parley

“The psychiatric nurse appreciates a situation that provides an opportunity for her to form constructive personal relationships with her patients,” Parley wrote. “She likes to be involved in treatments that give her patients the most benefit with the least mental or physical discomfort, and she enjoys seeing results from her work. Anyone who has watched LSD properly used knows LSD is rewarding in all these areas.”

One of Osmond’s major theories was that LSD could provoke an experience akin to a psychotic episode and, when administered to doctors and nurses, he posited that it could help them to understand their patients, to see the world through their patients’ eyes. In conversation with CBC radio host Anna Maria Tremonti in 2016, Parley said she noticed that staff who took LSD did connect more with patients.

“Groups of staff were taking [LSD], they were trying to find out how their patients felt, and they were learning a lot because it upset your perceptions so badly,” Parley said. “I think they got a lot more empathy for patients. I noticed when I worked with nurses that had had LSD, they always seemed to understand their patients better.”

“I noticed when I worked with nurses that had had LSD, they always seemed to understand their patients better.”

Kay Parley

For many years Parley worked as a freelance journalist, writing about any number of subjects related to psychiatry and mental illness. She pursued two bachelor’s degrees (in sociology and education), taught at the Saskatchewan Polytechnic college for 18 years (retiring in 1987), and continued to paint.

Now well into her nineties, she’s kept as busy as ever. Parley’s first fantasy novel, The Grass People—all 480 pages of it—launched in 2018. Her paintings were exhibited at Regina’s Government House, the former residence of the Lieutenant-Governor of the North-West Territories, in 2019.

Though she only ingested LSD once, the insights gained from her experience she believed helped fuel her decades of service and creativity.

Tea? Or LSD?

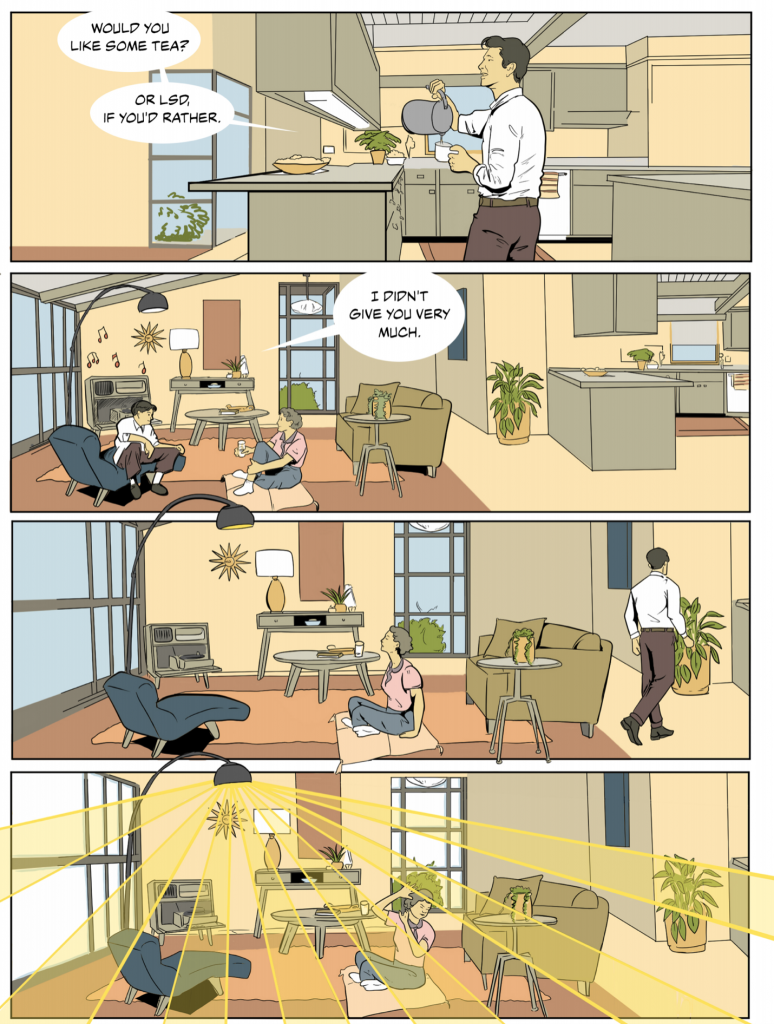

Aldous Huxley’s nephew Francis Huxley, a social anthropologist, came to Weyburn to study interaction among the wards to help with Osmond’s project to redesign of the institution. One night in 1958, Huxley invited Parley over to the Osmonds’ place where he was housesitting. As she recounts in her memoir, “He asks me for a cup of tea, and when I accept he suddenly seems to change his mind and says, ‘Or would you rather have LSD?’”

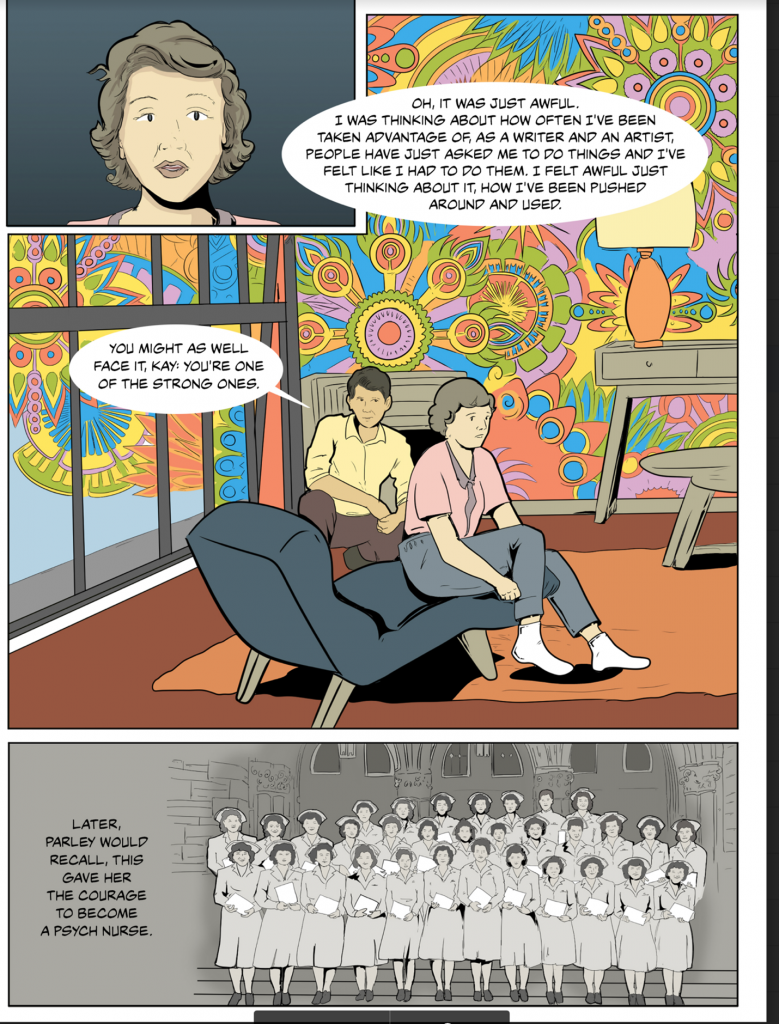

That fateful night, as Francis walked her home, he told her, “‘You may as well face it, you’re one of the strong ones.’” Dr. Osmond had banned Kay Parley from trying LSD because of her history of breakdowns, but in the end, that trip (and the conversation that followed) was the gentle, but fateful nudge that shifted her self-perception from frailty to courage.

“No wonder people reported achieving insight when under LSD. I got a totally new impression of myself in that instant, and it was to strengthen me many times through the years. I, who had considered myself a weakling, was one of the strong ones. It was a revelation.”

Kay Parley

“No wonder people reported achieving insight when under LSD,” she recounts. “I got a totally new impression of myself in that instant, and it was to strengthen me many times through the years. I, who had considered myself a weakling, was one of the strong ones. It was a revelation.”

Present-day psychiatry—indeed, any one of us—can learn much from Parley’s life. From the central roles community and creativity play in maintaining mental health, to the value of being open to change and experimentation (especially in finding unique, individualized pathways to healing), her story reaffirms that the hardest, scariest, and most circuitous roads are often the very ones that hit upon our deepest hidden treasures.

Art by Marialba Quesada.

Support the Eagle and the Condor’s Ayahuasca Religious Freedom Initiative

Take a minute to browse our stock:

Did you enjoy reading this article?

Please support Chacruna's work by donating to us. We are an independent organization and we offer free education and advocacy for psychedelic plant medicines. We are a team of dedicated volunteers!

Can you help Chacruna advance cultural understanding around these substances?