- Introduction to Women and Psychedelics - July 26, 2024

- Global History of Psychedelics: A Chacruna Series - October 4, 2023

- Can Psychedelics Promote Social Justice and Change the World? - August 30, 2021

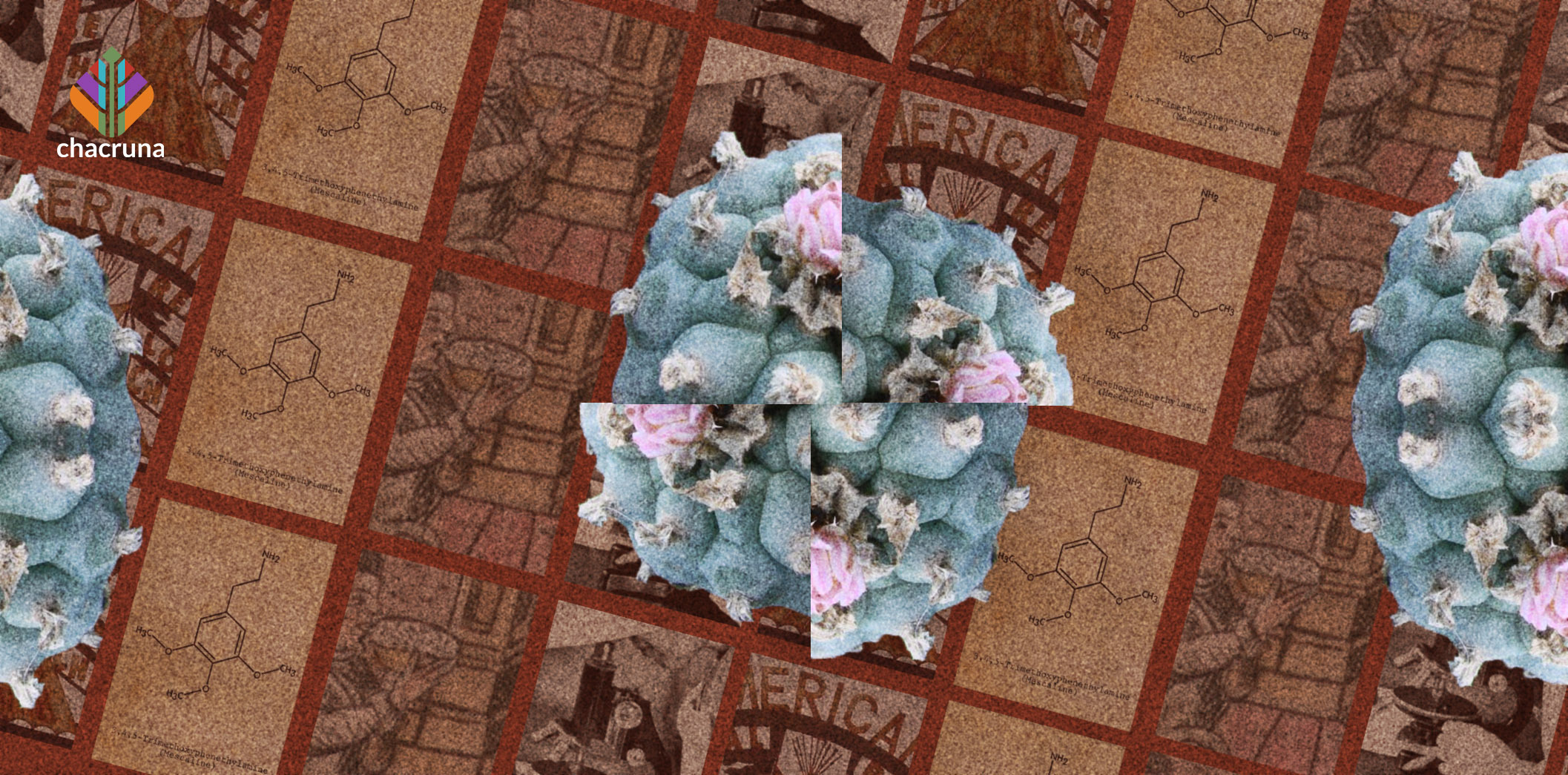

Peyote has been used for centuries by Indigenous people and its ancestral existence as a botanical species of cactus traces back even further. Oral traditions describe a founding story of “Peyote woman,” who fell asleep on a mound of cacti while distraught about the disappearance of her brothers in a war. She dreamt about their whereabouts and the community located them safely, praising her dreams and visions, which led her to them. The Peyote cactus, growing especially near the Rio Grande in Texas and Mexico, became a treasured plant and a Sacred plant within local Indigenous spirituality.

Peyote and Early Colonial History

European travelers recorded early observations of peyote practices in the 16th century, when Bernadino de Sahagúnwas told by his informants about a ceremony among Indigenous Mexican peyote users, the so called Chichimecas, living in the north. He wrote in 1560 “it produces in those who eat or drink it, terrible or ludicrous visions; the inebriation lasts for two or three days and then disappears.” Some decades later Francisco Hernández, the court physician to the king of Spain, when on a mission for cataloguing new species that could be of use for the medicinal pharmacopeia of the old world, noted that “peyotl” is used as an analgesic and that “it causes those devouring it to be able to foresee and to predict things.” From these early outsider descriptions, peyote and its effects became a subject of fascination, but also a source of tension between Indigenous and non-Indigenous perspectives on how to ascribe meaning to this plant and its effects on people.

These early mentions of the cactus were rediscovered when in the late 19th century German toxicologist Louis Lewin gathered peyote samples and tested extracts on frogs, pigeons, and rabbits, to determine a lethal dose. Throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries more and more western-trained scientists were drawn to peyote and their studies on the topic generated pharmacological interest and often reinforced western ways of describing and understanding the peyote cactus and its use.

Enter, Western Anthropology

The complex relationship between the plant and the people consuming the plant inspired different kinds of studies, largely conducted by anthropologists trained in Europe and the United States. Some of these investigators were interested in Indigenous spirituality and others were drawn to the psychoactive properties of the cactus itself. Over the 20th century anthropologists trained in Europe and the United States travelled to peyote sites to write about the customs and cultural habits of Indigenous peoples, including those that involved rituals and reverence towards hallucinogenic experiences. While many approached the topic sympathetically, especially in cases intended to introduce peyote to western readers, these anthropological accounts set the stage for an understanding of peyote and peyote-related rituals that were filtered through western perspectives.

“These early anthropological accounts … set the stage for an understanding of peyote-related rituals that were filtered through western perspectives.”

While anthropologists examined the social and cultural settings, scientists—botanists, chemists, and pharmacologists—increasingly invested in studies of the Peyote cactus in an attempt to identify, classify, and even harness its alkaloids in a manner that was much more scientific than cultural. Around 1900, as the cactus was being systematically investigated for its various chemical properties, mescaline drew attention as the “most interesting” alkaloid. The isolation of mescaline reinforced a growing divide between modern science and peyote-related cultural practices.

Native American Church

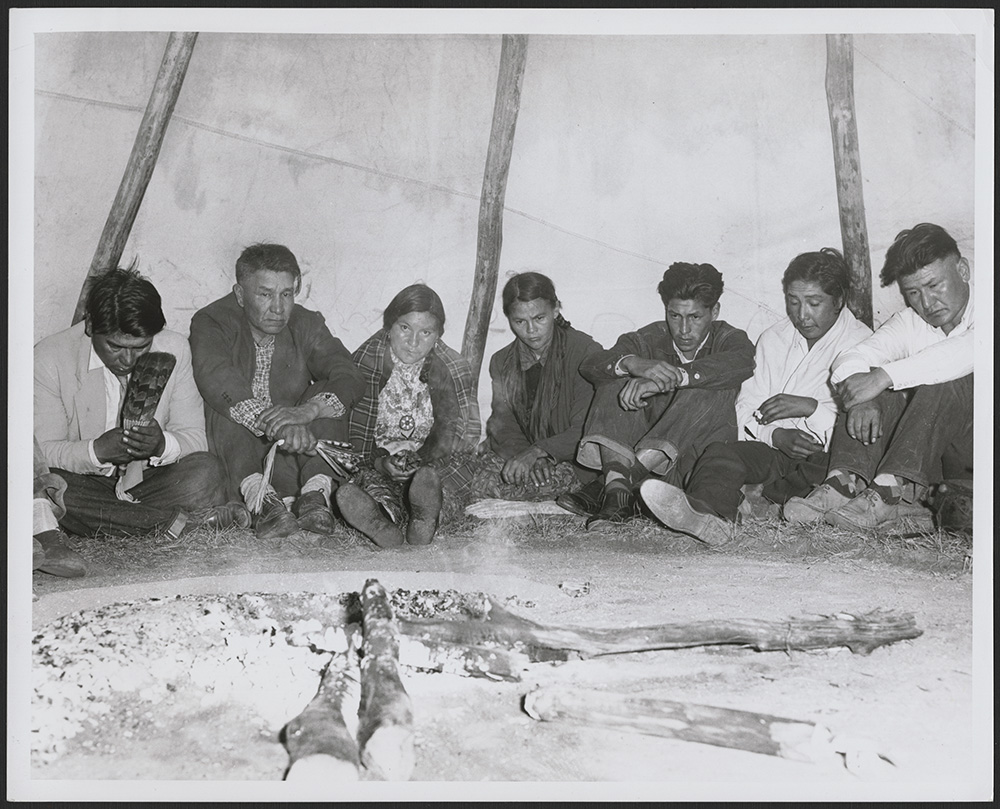

The first fully artificial synthesis was accomplished in the year 1919 by the Viennese chemist Ernst Späth, which coincided with another pivotal moment in this history: the legal recognition of the Native American Church (NAC). The NAC established a number of chapters, beginning in Oklahoma before spreading throughout the United States and into Canada. Described as a pan-Indigenous, Christian religion, it organized around peyote ceremonies as a sacrament (according to some descriptions), and incorporated peyote into its legal and cultural rites. NAC chapters lobbied state and provincial governments for legal, protected access to Peyote for worshipping purposes.

For some Indigenous leaders, the peyote rites offered a salve on the wounds caused by colonial oppression, particularly policies that apprehended children, and threatened to destroy languages, knowledge systems, and religious practices. In fact, Mr. Blackbear from the Kiowa-Apache tribe in Oklahoma, who was a significant leader in establishing legal rights for the NAC, argued that the songs accompanying peyote rituals were as important to the ritual as any other component, since many Indigenous youth no longer knew their native languages but could communicate with elders through song and prayer. For the NAC, peyote was not an experience that could be isolated or described in pharmacological terms alone, it was connected to the land, history, ancestors, language, spirituality, and health. To tease apart these elements was to lose the symbiosis that gave it meaning.

The Relationship Between Peyote and Mescaline

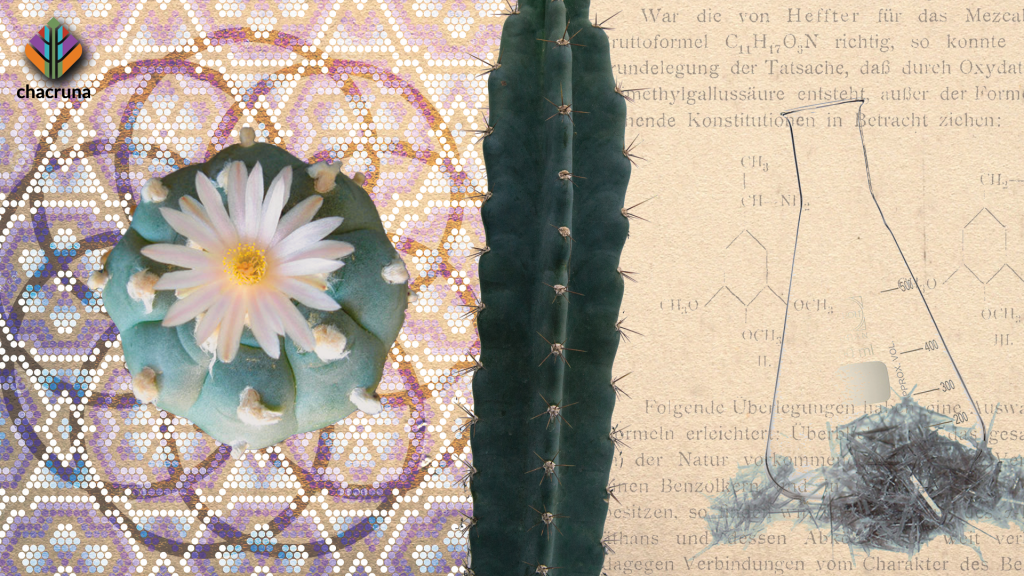

In some ways understanding the relationship between peyote and mescaline depends on who you listen to, or which disciplinary traditions you follow. Different perspectives over the last century have simultaneously framed the relationship between peyote and mescaline as harmonious and symbiotic, or entirely separate and distinctive. Materially mescaline is an inert chemical substance, whereas peyote is a living being, a succulent plant. As any plant it is a multicellular organism, which feeds on light, and goes through photosynthesis. According to the division of (scientific) labor, the study of this cactus is foremost the task of botany. But modern botany is not interested in the virtues of the plants.

The study of the psychoactive or medicinal properties and constituents of peyote became the task of pharmacologists, physicians, and psychologists. To first identify mescaline, it was necessary to bioassay a number of different components of the cactus and to compare its effects experientially. Since the hallucinatory propensities of the peyote cactus were by then considered to be its most distinguishing feature, and it was “mescaline” that had the strongest impact in this direction, it came to be conceived as the main psychoactive ingredient of the cactus. The chemical isolation of mescaline in 1898 by Arthur Heffter spurred on other searches. Long after Heffter’s identification, chemists realized that mescaline was also a natural component of the San Pedro cactus and in even lesser amounts in other cacti. This path of removing mescaline, then synthesizing it artificially effectively deracinated mescaline from the plant; its ecosystem, and the cultural meanings associated with that cactus were fundamentally muted. The synthesis of mescaline created a new “product,” which came to develop its own history and cultural meanings.

“The synthesis of mescaline created a new ‘product,’ which came to develop its own history and cultural meanings.”

The history of transforming peyote into mescaline is a story of separating plants from people. It has often been told as a story of success, or of scientific precision and triumph of science over nature, but this view is not the only way to interpret this history.

The history of peyote in relation to humans is much longer than this recent chapter, especially in the Americas, where the relationship between plants and people did not fit neatly into either “a science” or “a culture,” but has long existed as a more harmonious and complex set of relationships between land, people, plants, and the associated medico-spiritual, cultural, and recreational meanings.

Extracting a Cultural Experience

Some of the earliest non-Indigenous experimenters were immediately drawn to the hallucinogenic effects caused by ingesting peyote buttons. Humphry Osmond, in reviewing past descriptions found that Silas Weir Mitchell had claimed in 1896: “They were struck by the brilliant visual perceptual changes by peyote but white man does not relish the chewing of fibrous woody buttons, nor enjoy their soapy bitter taste.” This blunt description was followed by other white investigators complaining about the vomiting, or related difficulties digesting peyote with sometimes limited hallucinogenic trade-offs. For these early experimenters, the hallucinogenic properties were the most interesting, and they participated in a pursuit that led not only to the isolation of mescaline from peyote, but an extraction of the experience itself from specific cultural practices; the preparation, reflection, integration, and deference to the plant as a conveyor of healing and wisdom.

The more reductionist approaches enjoyed by a western scientific tradition celebrated the capacity to synthesize, or replicate effects of pharmacological substances, regardless of where these were consumed, who used them, or how users planned for or integrated these experiences. Pharmacists and chemists throughout the 20th century were praised for extracting chemical compounds from organic materials and repurposing them as medicines or other chemical products (fertilizer, rubber, etc.) that could be used anywhere, by anyone, with anticipated, and ideally standardized, results.

But mescaline also appealed to psychedelic researchers in the 1950s and 1960s who were intent on exploring the interactions between pharmacology and environment, famously coined by Timothy Leary as “set and setting.” The psychedelic research at mid-20th century grouped hallucinogenic substances that transcended the border between artificial and natural, between plants and inorganic compounds. Psychiatrists in Saskatchewan, including Osmond, participated in NAC ceremonies, which informed his own research on psychedelics and influenced others. Could synthesized mescaline, taken in ceremonial settings provide access to similar healing-spiritual experiences without having a local production of peyote? For Osmond, the link between the ceremony and the peyote plant was a sacred relationship that could not simply be replaced or replicated using mescaline—an alkaloid that was also present in other cacti, though he nonetheless felt that mescaline could be harnessed by western science to bring lessons into clinical research drawn from Indigenous wisdom regarding ceremony, intention, reflection, and integration.

Discover Indigenous Reciprocity Initiative of the Americas

Colonial Legacy

Some anthropologists pushed back against this colonial and enterprising agenda that deracinated plants from culture. Ethnobotanist Nancy Turner, for example, has explained that to appreciate Indigenous plant knowledge we cannot rely on western models or frameworks of classification. Extracting elements of plants from their environment disrupts the symbiosis that exists between people and plants.

“Debates today about the continuing relationship … between peyote and mescaline bear the scars of this longer history of colonialism and the extraction of plant matter from cultural practices.”

Debates today about the continuing relationship, if any, between peyote and mescaline bear the scars of this longer history of colonialism and the extraction of plant matter from cultural practices. How we understand the relationship between peyote and mescaline is important for scientific and ecological reasons but questioning this relationship should also encourage us to think about the cultural histories of mescaline and peyote—which come from very different traditions. Established through different cultural practices and knowledge systems, peyote and mescaline are vastly different. It is important to honour the original and diverse set of plant-based roots of mescaline, but to also recognize that its isolation and synthesis, now sets it on a different historical trajectory.

Feature Art by Karina Alvarez.

Take a minute to browse our stock:

Did you enjoy reading this article?

Please support Chacruna's work by donating to us. We are an independent organization and we offer free education and advocacy for psychedelic plant medicines. We are a team of dedicated volunteers!

Can you help Chacruna advance cultural understanding around these substances?