[This article does not constitute legal advice.]

On May 25, the Oregon Psilocybin Advisory Board (OPAB) will vote on whether to recommend adopting the proposed model regulatory framework for religious liberties and community access under the Oregon Psilocybin Services Act, also known as Measure 109. As the author of the framework, I have received an enormous amount of feedback about it. Although the overwhelming majority of the feedback has been highly favorable, some concerns have been raised. Most of these concerns are based on misunderstandings about the proposal or the law; a few of them are not. This article is offered to help policymakers navigate some of the legal and policy issues underlying the proposal and the concerns that have been raised.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

-

- What is the entheogenic practitioner framework?

- What are the key considerations for the framework?

- What privileges would be offered under the framework?

- Who would be eligible for the privileges?

- Is the framework legally allowed under Measure 109?

- “Peer-support assistance” and facilitator-to-client ratios under the framework

- Other facilitation issues addressed in the framework

- Facilitators who participate in ceremony (spoiler: they won’t be taking psilocybin)

- Screening, preparation sessions, and integration

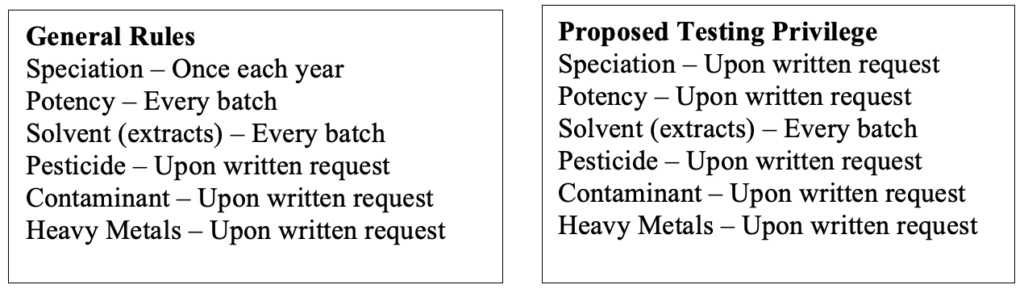

- Testing rules under the framework and manufacturing endorsement

- Products rules under the framework and manufacturing endorsement

- The framework’s relationship to the rest of the M109 regulations

- Didn’t OPAB already make final recommendations on products and testing rules?

- An affordable “community access” framework that bypasses religious liberties issues

- Conclusion

1. What is the entheogenic practitioner framework?

Measure 109 gives repeated attention to the balance of safety with affordability and accessibility. Safety and accessibility are thought to stand in tension with one another. Nearly every conceivable regulation that adds to the safety of a session also adds to its costs. Balancing safety and accessibility is a delicate act. If the safeguards and safety protocols are higher than needed, they create unnecessary paywalls that will make the transformative potential of the psilocybin experience unavailable to already-marginalized communities. If the safeguards and protocols are too low, people will be harmed.

A one-size-fits-all regulatory framework that does not provide flexibility to responsible practitioners who work with responsible clients will unnecessarily inflate the costs of goods and services to the detriment of low-income communities.

The biggest challenge of balancing safety with affordability under M109 is that people will take psilocybin under M109 for different reasons. As individuals, clients will also come into the program with different needs. A one-size-fits-all regulatory framework that does not provide flexibility to responsible practitioners who work with responsible clients will unnecessarily inflate the costs of goods and services to the detriment of low-income communities. A little bit of flexibility can result in a dramatically more affordable program.

The entheogenic practitioner framework is a model regulatory framework for how Oregon could provide flexibility to responsible communities who work with psilocybin. It would prevent responsible communities from having to pay for safeguards that are out of proportion to the particular safety needs of their community.

Its two main goals are: 1) To create an affordable community-access model of psilocybin services within M109 that would make legal psilocybin services within reach of all Oregonians regardless of socioeconomic status 2) To create enough flexibility that there are religiously- and culturally-sensitive, decolonized options for sincere communities that want to work with psilocybin aboveground on a not-for-profit basis.

It is a community-use paradigm. It was inspired by Indigenous, religious, and community-based practices of sincere communities who work with psychedelics. It is informed by stakeholder input and federal religious freedom laws. It was designed to fit completely and legally within the broader M109 framework, so that any necessary amendments would be made to the framework, rather than to M109. To that end, the framework was designed as a flexible framework that could be modified in response to any safety, legal, or other concerns.

2. What are the considerations and goals of the framework?

The framework was designed and revised with several primary goals and considerations in mind:

a) It must fit within the existing Measure 109 framework, so that it can be adopted through the administrative rulemaking process without a change of the M109 statute.

b) Given the Oregon constitution’s protection of both the religious and the non-religious,[1] as well as potential concerns under the Establishment and Equal Protection clauses of the Oregon and US Constitutions, the regulations should not give preferences to “religious” over “non-religious” organizations or individuals. Accordingly, the criteria for who may operate within the entheogenic framework must not be limited to religious participants.

c) It should invite a broad range of underground psilocybin practitioners to come above ground into the safety of the Measure 109 system, where there is more oversight, accountability, and unrestrained access to medical and law enforcement assistance. To do this inclusively, it should consider a broad range of practices and traditions, from traditional Indigenous communities, to contemporary Western, Eastern, and neo-shamanic traditions that use psychedelics, to secular and atheist practitioners that work with psychedelics in beneficial ways.

d) It must strive to make psilocybin services within financial reach of the 520,000 Oregonians living in poverty. To do this, it must avoid or minimize regulations that would create unnecessary paywalls. Regulations create unnecessary paywalls when they would drive up the costs of services or products without addressing real, articulable safety concerns or serve other purposes that are vital to the program’s functioning.

e) It should allow communities to utilize community resources as a way of providing affordable access.

f) The regulations must provide meaningful oversight and accountability for operators within the community-use paradigm. The particular safety needs are:

i. Screening new members to identify and provide information and advice about potential contraindications, within the limits of a facilitator’s scope of practice;

ii. Disclosing the risks associated with taking psilocybin, whether or not particularized to the individual client

iii. Ensuring that informed consent is obtained prior to an administration session;

iv. Preventing client abuse by facilitators and other community members;

v. Ensuring that community practice is conducted in a safe manner; and

vi. Providing adequate support and assistance before, during, and after a psilocybin administration session, and

g) It should be simple enough to administer that it does not cause a substantial burden on the OHA Psilocybin Services program’s limited resources.

Join Chacruna’s Studies in Psychedelic Justice

3. What privileges that would be offered under the framework?

It may be helpful to conceive of the privileges as falling into one of two categories: 1) Privileges that are intended primarily to help reduce the cost for clients to access the program; or 2) Privileges that are intended primarily to promote equity in the program that is unrelated to cost, such as religious sensitivity and decolonized paradigms of access. Many privileges advance both goals.

Within the category of cost savings, the proposal would offer the following privileges to eligible applicants:

(a) To have group and outdoor administration sessions;

(b) To have ceremonies that meet their facilitator requirements through the use of peer support

(c) To create a manufacturing endorsement that would allow:

i. A manufacturer to be located on the premises of a service center;

ii. To not have its psilocybin products tested except upon written request of OHA or upon its own initiative;

iii. To offer fresh mushrooms for retail sale, if those mushrooms are grown by the manufacturer that is co-located with a service center;

(d) To have any number of administration sessions for a client after completing one preparation session;

(e) To have any number of psilocybin administration sessions for a client who has submitted one completed Client Information Form within the last 12 months; and

(f) For facilitators to actively participate in ceremonies in which the entheogenic facilitator is providing psilocybin services, provided that the entheogenic facilitator does not consume psilocybin products during the ceremony.

i. For manufacturers to store, handle, and discard psilocybin products in a manner in accordance with one’s beliefs or convictions, providing that such storage, handling, and discarding are safe;

ii. To not be restricted in the species of psilocybin-containing mushrooms that may be cultivated; and

iii. For manufacturers to not be restricted in the growing techniques or growing substrates that may be used.

The intention here is not to reserve any particular privilege only for people who have been granted privileges, but to offer a comprehensive list of the items that would promote affordability and equity within a community-use paradigm.

The framework’s list of privileges is intended to be a comprehensive list of the cost saving and other equitable measures that, in its author’s view, should be incorporated within the M109 community-use framework. Many items on these lists can and should be available to all participants in the M109 program. For instance, group administration sessions will likely to be permitted for all participants in M109, but in the absence of knowing what the final rules will ultimately be, they have been included to ensure they are not omitted. The intention here is not to reserve any particular privilege only for people who have been granted privileges, but to offer a comprehensive list of the items that would promote affordability and equity within a community-use paradigm. If ultimately adopted by OHA, the list of privileges should contain only items that are not otherwise allowed in the rest of the M109 program.

4. Who would be eligible for the privileges?

The question of who should be granted privileges under the framework has generated more critical attention than any other aspect. The draft framework proposes to grant them to people who would use them for “religious or spiritual” purposes. Some have raised concerns that this is close enough to preferring religions that it becomes legally and constitutionally problematic. Others have raised concern that the “spiritual use” category is so subjective that it is effectively meaningless.

What follows is a description of the various approaches that rule makers in Oregon and elsewhere could consider.

The “Religious Only” Approach

The first and most restrictive approach would be to grant privileges only to religious organizations that would use the privileges for religious activities. Although courts and regulators have struggled to settle on a single metric for determining what counts as “religious,” several ways have gained traction, foremost among which are the “Meyers test,” the IRS’s test, and the so-called “functional test.”[2]

The logic behind is this approach is that granting religious organizations such privileges is what federal law already requires the federal government to do and is the bare minimum the state should do. In fact, if a bona fide religious organization safely uses controlled substances as part of its sincere religious practice, federal religious freedom law requires the federal government to exempt the organization from the federal Controlled Substances Act. This is a much more dramatic request than anything in sought in the entheogenic framework. Oregon’s program should attempt to mirror federal civil rights laws as nearly as possible.

In Oregon, the problem with the “religious only” approach is that it would likely violate the Oregon Constitution, which prohibits the state from granting preferences to the religious over the non-religious.[3] This approach may, however, be viable, or even represent a mandatory minimum civil rights floor, in other states where the law protects religious but not non-religious people.

The “Religious or Spiritual” Approach

This is the option recommended in the draft framework that OPAB will vote on. This option would make the privileges available to people who would use them in furtherance of “religious” or “spiritual” activity. The fastest growing category of religious identity in the US is people who identify as “spiritual but not religious.” The religious or spiritual approach recognizes that spiritual exploration and development need not conform to conventional definitions of “religion” in order for it to be a public and social good that deserves protection.

The best word I could find for this was “entheogenic” because, in my understanding, that word includes both religious and non-religious spiritual practice involving psychedelic substances.[4]

Although inspired in part by religious practice utilizing psilocybin and other psychedelics, the framework was specifically designed to avoid giving any preferences to religious individuals or organizations. It was also designed to avoid giving clients financial incentives to seek psilocybin in religious settings. The primary way it does this is by fully allowing secular organizations to operate with all of the same privileges that are available to religious organizations.

In my view, this is the most conservative and restrictive approach that Oregon could legally adopt while not ignoring the religious issue. It would offer the privileges to people who use psilocybin in a manner defined by religious or spiritual intentions that are pursued with sincerity but discriminates based on the intention with which one takes psilocybin; a nonprofit community health clinic, for example, would be ineligible for the privileges under this approach.

In Oregon, the “religious or spiritual” approach is preferrable to the “religious only” approach because it would dramatically lessen constitutional concerns around granting preferences to the religious over the non-religious. However, some have questioned whether granting privileges to only “religious” and to nonreligious “spiritual” providers might nevertheless create constitutional concerns about giving preferences to religions. This view would see the activity of the “spiritual but not religious” organizations as still being “religious” from a legal perspective, and thus still creating some potential legal concern in Oregon.

The “Community” Approach

This approach would offer privileges not necessarily according to the type of benefits one seeks through psilocybin, but rather through the fact that psilocybin is provided by and used within a community-based organization. The benefit of this approach is that it would expand affordable access to people regardless of why they’re taking psilocybin, and it would further remove financial incentives for clients to take psilocybin in religious settings. By selecting this approach, Oregon could adopt regulations that help encourage the proliferation of low-income, nonprofit psilocybin service centers that assist clients in achieving a wide range of social and public goods.

The general idea behind a community-based model would be to allow responsible psilocybin professionals and responsible clients to utilize community resources to provide access that is safe and affordable.

What is meant by a “community setting”? The general idea behind a community-based model would be to allow responsible psilocybin professionals and responsible clients to utilize community resources to provide access that is safe and affordable. Communities pool and exchange resources to meet community needs. I believe limiting the privileges of nonprofits[5] and cooperatives[6] would be sufficient to achieve the desired result, although there are other ways this could be done. Also, to help remove the religious moorings of the community approach, the phrase “entheogenic” could be replaced with “community” throughout.

This would also resolve any potential concern that OHA is prohibited from promulgating rules that protect or prefer religious activity.

Here is a way (Privileges and Duties of Community Practitioners [v.1]) that Oregon could revise the framework to convert it into a religiously- and spiritually-neutral model for community access.[7]

The “Anybody Who Wants Them” Approach

The “anybody who wants them” approach argues that if the privileges are safe for one type of psilocybin use, then they should be equally safe and available for every use of psilocybin by every client under M109. This approach would cram religious organizations, medical and therapeutic practice, and luxury resorts into a one-size-fits-all system that assumes all uses have the same considerations and must be governed by the same set of rules. This approach has been criticized by Matthew Johnson of Johns Hopkins in his article Consciousness, Religion, and Gurus: Pitfalls of Psychedelic Medicine,[8] in which he warns against service providers introducing religious beliefs within the context of clinical and scientific paradigms and notes that some considerations in clinical practice “do not relate to the use of psychedelics by religions or Indigenous societies.” Which is to say that Indigenous and religious paradigms of use have different considerations and should be handled differently in a regulated system.

That said, there is wisdom in keeping the entheogenic/community practitioners and the non-entheogenic/non-community practitioners operating under as many of the same rules as possible, particularly to avoid the creation of financial or other incentives to drive people to use psilocybin in a use-paradigm that is different than what they are seeking.[9]

The concerns about employing the “anybody who wants them” approach do not apply equally to all privileges. In particular, the use of peer-support to provide safety during a psilocybin administration session would often be ill-suited in the context of tourist destinations where clients are largely unacquainted with one another. Additionally, tourists are perhaps more likely to be psychedelically naïve than people who belong to a community that works with psilocybin. It may also be desirable in more casual settings to have the dosing precision that can only be achieved through mandatory concentration (aka “potency”) testing.

Still, this perspective does have some merit. As noted above, it is desirable that many if not most of the “privileges” listed in the framework are available to all participants in the M109 program. Those that could not be safely offered to all participants within M109 should be reserved as privileges for responsible communities.[10]

Summary on the Eligibility for Privileges

In the months since drafting the proposed framework, my thinking has evolved[11] and I have come to favor offering the privileges on the basis of the provider being a community-based organization that is run on a nonprofit basis. This would provide affordable access to the most people for the widest array of beneficial uses and would remove financial incentives for people to seek psilocybin services in a use paradigm that deviates from the client’s objectives in taking psilocybin.

Of the list of privileges considered in the framework, all of them (or some version of them) could be safely adopted throughout the entire M109 program with the potential exceptions of client-provided peer-support assistance and relaxed potency testing. Those privileges, and ceremonial peer-support in particular, are better suited for use within the context of responsible community-based practice.

5. Is the framework legally allowed under Measure 109?

The proposed framework was specifically designed to fit completely and legally within the broader M109 framework. No provision of the framework would require or permit any client or psilocybin license-holder to violate M109.

Some have also wondered whether OHA has statutory rulemaking authority under M109 to adopt rules protecting religious activity. This concern was recently addressed by the Psychedelic Bar Association’s Religious Use Committee in its Statement Regarding the Oregon Health Authority’s Notice of Proposed Rulemaking.

To quote from the Committee’s analysis:

-

- Section 24 empowers the OHA to adopt rules that designate different types of manufacturing activities and endorsements that allow licensed entities to engage in those activities. The section gives the agency broad discretion to determine the types of manufacturing activities and endorsements it will allow. Nothing in Section 24 prohibits the OHA from creating a religious manufacturing endorsement as recommended by OPAB’s Licensing Subcommittee.

- Section 25 empowers the OHA to create rules that limit psilocybin product quantities. Nothing in the rules prohibits the agency from creating different rules regarding quantity limits for different types of licensed entities such as religious and secular organizations.

- Section 26 empowers the OHA to create rules regarding service center licenses and fees. Subsection 3(b) gives the OHA the power to set application, licensure, and renewal fees for psilocybin service center operators. It does not require those fees to be uniform across the industry, which gives the OHA discretion to establish different fee structures for different types of service centers, such as religious and secular organizations.

- Subsection 3(d) gives the agency power to require service center operators to meet public health and safety standards and industry best practices established by the agency. It explicitly gives the OHA the power to set those standards and best practices and does not prohibit the agency from creating different standards and best practices for various types of service centers.

- Section 8(c) empowers the OHA to adopt rules necessary to carry out the intent and provision of sections 3 to 129, “including rules that the authority considers necessary to protect the public health and safety.” The addition of the word “including” suggests that public health and safety are two examples of the goals of sections 3 to 129, rather than an exhaustive list. Otherwise, Section 8(c) would have included words such as “consisting of,” or “comprising rules that the authority considers necessary to protect the public health and safety.” Consequently, Section 8(c) indicates that the powers given to the OHA to carry out provisions 3 to 129 are broader than those that protect public health and safety. In other words, the agency is empowered to adopt rules that promote other values, such as the free exercise of religion or the accessibility of psilocybin services.

- Finally, in addition to Section 8(c), which applies only to sections 3 to 129, Subsection (C) empowers the OHA to regulate the use of psilocybin products and psilocybin services “for other purposes” deemed necessary or appropriate by the authority. The phrase “for other purposes” indicates that the OHA may create rules that achieve purposes that are not explicitly stated in sections 3 to 129 or implied from them. This too means that OHA can create rules for the purposes of accommodating religious practice.

Moreover, one of the express purposes and policies of M109 is to “establish a comprehensive regulatory framework concerning psilocybin products and psilocybin services under state law.” ORS 475A.205(1)(e)(B). A framework that does not address religious and community use is not a comprehensive framework. In short, M109 gives clear rulemaking authority to OHA to adopt rules that would optimize for religious, spiritual, and/or community use and create affordable pathways for access.

6. “Peer-support assistance” and facilitator-to-client ratios under the framework

OHA is expected to adopt a single facilitator-to-client ratio that must be adhered to in all group administration sessions. This would be a one-size-fits-all ratio that must fit every circumstance. While a single “golden ratio” is attractive for its simplicity, in truth there are a number of factors that would need to be considered when determining the number of facilitators that are minimally needed to safely supervise a group session. The list I’ve compiled includes:

(a) Any mental or behavioral health condition of any member that increases the likelihood of requiring support during the session.

(b) The amount of psilocybin being consumed by clients in the group;

(c) The group and its members’ prior experience with psilocybin or other entheogenic plants or psychedelics;

(d) The types of activities the group intends to engage in while on psilocybin;

(e) The facilitators’ familiarity with the clients participating in a ceremony;

(f) The amount of cohesion or discord present in the group, if known to the facilitator;

(g) The relevant experience, skill, and number of facilitators who are providing supervision;

Within a community context, where people exist in relationship with one another and the organization is not driven by profit, responsible professionals can be trained and trusted to be prudent in assessing and applying these factors.

Within a community context, where people exist in relationship with one another and the organization is not driven by profit, responsible professionals can be trained and trusted to be prudent in assessing and applying these factors. If community facilitators are given the flexibility to provide an appropriate amount of facilitator supervision that gives attention to circumstances, it could reduce the cost of an individual session by more than 50%, depending on what facilitator-to-client ratio Oregon otherwise chooses.

Consider, for instance, the earlier Licensing Subcommittee recommendation that the ratio be 3:1. Suppose there is a 10-person group consisting only of people who are highly experienced as individuals and who have had years of association together as community without incident. Now suppose the group’s dose falls within a range 1.0-1.5g of dried cubensis mushrooms. Under these circumstances, it is conceivable that the group could safely and responsibly conduct the group session with only 1 facilitator present. Under a 3:1 ratio, they would need to have 4 facilitators on hand to “supervise.” Particularly, given the expectation of a non-directive approach, most of these facilitators will be sitting idle for most of the session. By allowing the group to exercise discretion in judging how many facilitators are needed, it could reduce its facilitation costs by up to 75%.

Under these circumstances, it is appropriate to allow responsible communities to have such flexibility. The proposed framework would offer as a privilege the discretion to deviate from the generally applicable facilitator-to-client ratios that govern the rest of the M109 program. In exercising that discretion, the facilitators and service center operators would both be under a duty to ensure that group sessions have appropriate support under the circumstances of that session. Exercising good judgment in the amount of facilitation a ceremonial session needs will be a core competency of entheogenic/community facilitators. If a client or other person is hurt because a facilitator and service center failed to exercise reasonable judgment in the exercise of this discretion, they face administrative discipline—including possible permanent loss of licensure, depending on the seriousness of the mistake.

To help fill in any gaps that might be caused by a lower facilitator-to-client ratio, the framework would require a community to train and certify its members to provide “peer-support assistance” in-ceremony. A recent article by the Green Light Law Group describes peer support in the framework as “one client assisting another client during a ceremony.”

Certification of peer-support providers ensures there are experienced and responsible community members on hand to help ensure client safety and support, particularly of newcomers to the community. The framework would allow the State to insist that a certain percentage of the people in these group sessions have undergone some manner of training or vetting by the community, before “certifying” them as being ready to provide peer-support. The idea here is to allow more autonomy and flexibility to communities in how they assure client safety while also allowing the use of community resources to provide more affordable access.

To be “certified” under the framework, a community service center must provide synchronous instruction to the person that is in alignment with the facilitators’ code of conduct and other generally-accepted best practices. The service center must certify that the client is qualified and capable of providing peer-support assistance before they can be permitted to deviate from the generally-applicable ratio.

If the State wanted to regulate the provision of peer support, it would have virtually endless options to do so. The framework offers some ways the State could do that. One of them is to require that clients who provide peer-support assistance have to have attended a given number of sessions with the community before they can be eligible. This would require a fixed amount of prior involvement within the community before beginning to serve in a peer support role, and it would encourage a more gradual transition to increased reliance on peer-support assistance, as well as the slower growth of these organizations.

Another way the State could regulate peer-support assistance would be to fix the ratio of peer-support to non-peer support clients. This would effectively regulate the “community elder to newcomer ratio” to reduce the potential unknown variables that come with the addition of new community members. This ratio could be 1 “elder” who provides peer support assistance for every 2 or 3 who do not. Or it could be 2 or 3 elders for every 1 newcomer.

Another option not discussed in the framework would be to impose requirements on the instruction provided to peer-support assistance providers by a service center.

If the State wishes to set a minimum level of involvement for elders and a “elder to newcomer” ratio, it would be appropriate for those numbers to be initially conservative. I believe a 5-ceremony minimum and a 1:2 elder-to-newcomer ratio to be sufficiently cautious, yet sufficiently flexible, but reasonable minds may differ and Oregon may wish to use different numbers, particularly at program inception.

To summarize, the framework would give community facilitators and service centers the privilege of having the flexibility to deviate from generally-applicable facilitator-to-client ratios in order to provide safeguards that are in proportion to the actual safety needs of a particular group administration session. Before any deviation could occur, the supervising facilitators and service center would need to consider the relevant factors for how much and what type of supervision and support is required, the mandatory factors for consideration including things such as: the experience of the group in taking psilocybin together; members’ prior experience with psilocybin or other psychedelics; group members’ mental or behavioral health conditions that may require special support; the relevant experience and skill of the clients who are providing peer-support assistance; and the relevant experience, skill, and number of facilitators who are providing supervision. The peer-support assistance privilege, alone, would create opportunities with M109 to offer significantly lower-cost administration sessions—perhaps more than 50% lower— within the context of responsible community use.

This “peer-support assistance” model was inspired by the practices of the Santo Daime church. For more information about how ceremonial peer-support can be used to offer safe group/ceremonial healing, watch this interview I did with Padrinho Jonathan Goldman of the Church of the Holy Light of the Queen, the Santo Daime branch that successfully sued the federal government for their right to drink daime (aka ayahuasca) in 2008.

7. Other facilitation issues addressed in the framework

a. Facilitators who participate in ceremony (spoiler: they won’t be taking psilocybin)

One common misconception about M109 is that all facilitation must always be non-directive in its approach.

One common misconception about M109 is that all facilitation must always be non-directive in its approach. I, too, was under this misperception until a lawyer who participated in the drafting of M109 corrected me on this issue.[12] M109 discusses nondirective facilitation in two places. In one of them, OPAB is charged with making recommendations about facilitator education programs that must give “particular consideration to facilitation skills that are affirming, non-judgmental, and non-directive.” ORS 475A.230(6)(a)(A). In the other, OHA is charged with determining the qualifications, training, education, and fitness of a person who wants to obtain a facilitator’s license, and they must make this determination “giving particular consideration to facilitation skills that are affirming, non-judgmental, and non-directive.” ORS 475A.375(1)(a). Neither of these sections requires that facilitation actually be non-directive.

The framework would allow community facilitators to participate in ceremony while functioning as a facilitator, subject to limitations. The limitations are: facilitators must remain alert and attentive to client needs and intervene when necessary to enhance, preserve, or restore client safety. Also, facilitators may never take psilocybin while serving as a facilitator. ORS 475A.455.

This privilege was added to the list in anticipation that OHA might enact regulations that prohibit use of directive facilitation. This would prevent community facilitators from having to sit idly during an administrative session and remove disincentives for facilitators to volunteer their time.

b. Screening, preparation sessions, and integration

All of the statutory M109 rules would apply to entheogenic/community practitioners. This includes:

- All clients must undergo standard screening and intake, including completion of a Client Information Form;

- All clients must receive at least one preparation session as otherwise provided in the program; and

- All clients must be offered an integration as otherwise provided in the program.

To the extent that the framework addresses these issues, it would give clients who seek services in a community-use paradigm flexibility in choosing how much support they want or need after and in-between administration sessions. It would give clients to option of attending repeated administration sessions without forcing them to repeat the preparation session in-between administration sessions. It would also allow clients to undergo intake screening only once annually. This would allow clients to avoid paying for support that may not be needed or wanted.

On the other side, the framework would create an option for community facilitators to offer multiple preparation and integration sessions, if the clients so desired. This was added to the list of privilege in anticipation that the generally-applicable regulations might limit clients and facilitators to one preparation and one integration session, as was discussed by the OPAB Training Subcommittee. The goal here is ensuring that clients are able to get the support they need or want.

These considerations are not wholly unique to the community-use paradigm and may be considered for adoption across the broader M109 program.

8. Testing rules under the framework and manufacturing endorsement

Mushrooms cost almost nothing to grow. Someone recently told me that once a psilocybin mushroom grow is up and running, it costs about $5 in material to grow a whole pound. Someone else recently told me about a psychedelic investors conference where a presenter said that one psilocybin capsule in Oregon will cost $750.

While it is certainly true that OHA does not “regulate costs,” it would be irresponsible to pretend that regulations do not drive costs to a large extent.[13] The framework aims to empower communities who work with psilocybin mushrooms to grow their own and to keep their exchange as “uncommercial” as possible under M109. This is another aspect of using community resources to help provide low-cost access. The idea of a “community mushroom garden” could be seen as similar to homegrown cannabis, which is an uncontroversial part of Oregon’s cannabis program. Onsite, direct “farm-to-table”-style product chain helps ensure that low-income communities aren’t forced to pay $750 per capsule.

The potency testing under the newly-adopted testing rules makes onsite farm-to-table grows impractical or impossible. Potency would need to be tested every “harvest lot,” which means small community grows would have to pay for testing every time they harvest any mushrooms within a 24-hour period. OAR 333-333-2020(10), 333-333-7040(1 ).

Within the M109 framework, the harms that could be caused by less-frequently-tested, community-grown mushrooms would be practically non-existent in the context of responsible community use and cannot be used as an honest justification for rules that would effectively require communities who work with psilocybin to procure their product through overpriced commercial channels. When regulations drive up costs without serving important government interests, they raise paywalls, deepen inequities across racial, gender, class, and other divides.

An entheogenic or community manufacturing endorsement should allow for purchase and consumption of psilocybin products that have not had every harvest lot potency tested and that do not undergo routine speciation testing. The potential safety benefits of mandatory potency testing on every harvest of mushrooms are not enough to justify their likely exclusionary impact on low-income Oregonians.

Discover the Indigenous Reciprocity Initiative of the Americas

9. Products rules under the framework and manufacturing endorsement

As noted above, psilocybin-containing mushrooms cost almost nothing to grow but are projected by some investors to sell for around $750 per capsule.

As noted above, psilocybin-containing mushrooms cost almost nothing to grow but are projected by some investors to sell for around $750 per capsule. The impetus behind the manufacturing privileges were several: allow communities to produce and offer low-cost psilocybin products; allow religious communities to grow, handle, store, and discard products in ways that reflect their sincerely-held beliefs; and to provide flexibility to communities who work with mushroom species other than Psilocybe cubensis.

A direct farm-to-table product pipeline allows for psilocybin products that are not outrageously expensive, and many communities who work with psilocybin and other plant medicines report that they have better experiential outcomes when they’ve developed a relationship with an entheogenic plant or mushroom while it is still alive.

Allowing communities to work with species other than Psilocybe cubensis has been one of the more controversial aspects of this proposal. OPAB could easily remove that portion of the framework if it chose.

An entheogenic or community manufacturing endorsement should allow for purchase and consumption of psilocybin products that were grown at a service center that is co-licensed as a psilocybin manufacturer. The anticipated costs of procuring mushrooms through commercialized channels, together with no clear enhancement of client or public safety, do justify their likely exclusionary impact on low-income Oregonians.

10. The framework’s relationship to the rest of the M109 regulations

Under the proposed framework, the holder of privileges will be subject to all of the M109 statute approved by voters and virtually all of the same OHA-adopted regulations that govern the rest of the M109 program. This includes: undergoing the same facilitator training; sitting for the same licensing examination; seek identical licensure; being subject to the same disciplinary oversight, and following all of the same program rules as every other person who participates under the M109 program unless otherwise stated.

What is the “otherwise stated” part? The exemptions are relatively few and minor in comparison to the provisions of the program that will not be exemption. The entire list can be found at proposed OAR XXX-XXX-XXX5 of the draft framework, and the privileges are different for different types of license-holders. Other than the possible exemptions in XXX5, 100% of the rest of the regulations would apply to people holding privileges.

During the March 3, 2022 OPAB Licensing Subcommittee meeting, OPAB member Barb Hansen cited this as a critical consideration in her decision to vote in favor of recommending adoption of the model framework.

11. Didn’t OPAB already make recommendations on products and testing rules?

In November, OPAB made recommendations about products and testing. Those recommendations did not consider the issue of community and entheogenic use, as those conversations began in earnest at the February 2, 2022, Licensing Subcommittee in which the Committee heard presentations on religious and entheogenic community use.

OHA, in its May 20, 2022 letter to the public addressing the first set of rules it adopted, said: “Many members of the public expressed support for an ‘Entheogenic Framework’ for licensing…. Because the framework proposes exceptions to rules that have not yet been drafted, and because the Oregon Psilocybin Advisory Board has yet to consider the proposal, OPS did not address these comments in the current rulemaking.”

Accordingly, OHA is waiting on OPAB to review the matter before it adopts rules that address issues raised in the framework.

Watch recordings here

12. An affordable “community access” framework that ignores the religious liberties problem

Part of my objective in writing this long article is to remove any legal pretext that might be offered as a basis for refusing to adopt some adaptation of the framework. For the reasons that are described in the sections of this article entitled “Is the framework legal under Measure 109?” and “Who would be eligible for the privileges?,” many people believe it would be bad faith for Oregon to claim it lacks the legal authority to adopt some version of this framework, or that there is no incarnation of the framework that would not violate the Constitution or law.

I hope that by now there have been a sufficient number of “clearly secular purposes” described for adopting the framework that there is no remaining good faith argument that the framework would create concern about Oregon “establishing” religion for the purposes of the Establishment Clauses of the Oregon and US Constitutions.[14] To recap, those “clearly secular” reasons are many, and include affordability, decolonization, cultural-sensitivity, and accommodating preferences for ceremonial-use paradigms. The framework also constitutes a harm reduction effort that recognizes the dangers now-occurring in the psychedelic underground, and it accommodates the 49% of people who indicated on OHA’s Community Interest Survey that their interest in taking psilocybin under M109 were “spiritual” in nature. Hence the “primary effect”[15] for purposes of Establishment Clause issues of the framework would be to make the M109 a more equitable and culturally-sensitive program.

Nevertheless, if the Oregon Department of Justice expressed concern that some aspects of the framework were “inspired by” Indigenous, religious, and community-based practices, there would nevertheless be an option to “scrub” the religious and other non-cost-related equity considerations from the framework and leave only the portions that were motivated by the desire to allow affordable community access. The problem with doing that is that we cannot remove the “religious liberties” aspects of the proposal while retaining its more decolonized and culturally-equitable character. Moreover, the religious liberties aspects of the framework were added to ensure that fewer or no unnecessary burdens are placed on religious exercise under M109.[16]

Nevertheless, in the interest of avoiding an Establishment Clause pretext for rejecting the framework, here are some things Oregon could remove to eliminate the imprint of religious liberties on the model, if it felt that such was legally required:

(a) From the manufacturing endorsement:

i. Manufacturers’ privilege to store, handle, and discard psilocybin products in a manner in accordance with one’s beliefs or convictions;

ii. The privilege of not being restricted in the species of psilocybin-containing mushrooms that may be cultivated; and

iii. The privilege to not be restricted in the growing techniques or growing substrates that may be used.

(b) The privilege of having ceremonies that are supervised from outside the ceremonial space; and

(c) The privilege of conducting ceremonies in which clients freely engage in rituals or exercises, provided they are safe;

(d) To have ceremonies that are “led” (which is distinct from “facilitated”) by one or more clients who have consumed psilocybin products;

The remaining proposal would be intentionally blind to the religious liberties problem and exist solely for the purposes of creating affordable, community access. The remaining attributes would be:

(a) To create a manufacturing endorsement that would allow:

i. A manufacturer to be located on the premises of a service center;

ii. To not have its psilocybin products tested except upon written request of OHA or upon its own initiative; and

iii. To offer fresh mushrooms for retail sale, if those mushrooms are grown at the manufacturer that is co-located with a service center;

(b) To have ceremonies that meet their facilitator requirements through with the use of peer support;

(c) To have group and outdoor administration sessions;

(d) To have any number of administration sessions for a client after completing one preparation session;

(e) To have any number of psilocybin administration sessions for a client who has submitted one completed Client Information Form within the last 12 months; and

(f) For facilitators actively participate in ceremonies in which the entheogenic facilitator is providing psilocybin services, provided that the entheogenic facilitator does not consume psilocybin products during the ceremony.

Here is an example (Privileges and Duties of Community Practitioners: Religiously-Sanitized Edition [v.1]) of what that might look like.[17]

13. Conclusion

OPAB members and OHA are empowered to ensure that this program serves Oregonians and people from all walks of life.

Oregon is about to create a new commercial marketplace for mystical-type experiences occasioned by psilocybin. The profound nature and lasting significance of these experiences dictate that they should be accessible and affordable to all people. A primary purpose of M109 is to ensure psilocybin is “a safe, accessible and affordable therapeutic option for all persons 21 years of age or older in this state for whom psilocybin may be appropriate.” ORS 475A.205(1)(c), emphasis added. But, with businesses already saying they are pursuing a national and international client base, there is a significant question about how much this program is going to actually serve the people Oregon. OPAB members and OHA are empowered to ensure that this program serves Oregonians and people from all walks of life.

Art by Trey Brasher.

[1] See, e.g., Meltebeke v. Bureau of Lab. & Indus., 322 Or at 147. (Oregon’s constitutional religious protections “extend… to religious believers and nonbelievers alike.”)

[2] George “Greg” Lake’s short book, The Law of Entheogenic Churches in the United States, covers these tests with elegant simplicity. Greg and his law partner Ian Benouis have posted an audiobook version of it free on YouTube.

[3] See, e.g., Meltebeke v. Bureau of Lab. & Indus., 322 Or at 147. (Oregon’s constitutional religious protections “extend… to religious believers and nonbelievers alike.”)

[4] One good piece of stakeholder feedback I received is that the even the category of “spiritual” use may exclude atheists or other secular communities who have a sincere meditative or contemplative practice but who do not believe in the existence of spirit. Accordingly, revised editions of the framework use the phrase “religious, spiritual, or contemplative” to describe the intentions that can be considered entheogenic in nature.

[5] Which are defined in Oregon to include mutual benefit corporations, public benefit corporations, and religious corporations. ORS 65.001(33).

[6] Defined at ORS 62.015 as an organization subject to Oregon’s Cooperative Corporations Act.

[7] The changes made to the framework include: removal of the requirement that an organization be organized for religious or spiritual purposes, or that one sign an attestation, in order to be eligible for privileges; removal of the more “religious” aspects of the framework that do not implicate accessibility and affordability issues, such as manufacturing privileges related to species diversity, growing substrates, and handling and discarding of psilocybin; removal of any requirement that ceremonial privileges be limited to those that relate to religious or spiritual practices; removal of the requirement that local land use and zoning ordinances be adopted in accordance with the Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act; and replacement of the word “entheogenic” with “community” throughout the framework.

[8] Note that this article is addressed to problems in “psychedelic medicine” and does not suggest that Indigenous, religious, or community use should not be respected within a regulated, adult-use program.

[9] Ismail Ali, Director of policy and advocacy for MAPS and a member of the OPAB Equity Subcommittee, noted this concern and expressed support for adopting many of the privileges throughout the broader M109 program during this March 3 meeting of the Subcommittee.

[10] This middle way of adopting most of the “privileges” throughout the whole M109 program, and reserving a few of them for sincere communities, was the approach recommended by David Bronner in his comment to the Oregon Health Authority.

[11] Contrary to popular belief, it is possible for one’s thinking to beneficially evolve as a result of dialog with critics.

[12] OHA appears to be under the same misconception. See OHA’s May 20, 2022 Letter to the Public in which they say “under the Oregon Psilocybin Services Act, facilitation is non-directive….”

[13] OHA’s May 20, 2022 letter: “…OPS does not have statutory authority to regulate the costs of psilocybin products or psilocybin services.”

[14] See, e.g., Eugene Sand & Gravel v. City of Eugene, 276 Or 1007.

[15] See, e.g., Eugene Sand & Gravel v. City of Eugene, 276 Or 1007.

[16] If laws that seek to protect religious liberties violate the Establishment Clause, then it’s a wonder we have any religious freedoms in the US. Moreover, religious accommodations are routinely made, e.g., people whose religion requires them to pray at times of the day, or to wear certain headdress, or not recite the Pledge of Allegiance.

[17] In addition to the changes described in footnote 7, the following privileges have been removed from this document: to supervise ceremonies that are led by clients who have consumed psilocybin products; to permit clients to freely engage in safe rituals or exercises; and to supervise ceremonies from outside the ceremonial space.

Take a minute to browse our stock:

Did you enjoy reading this article?

Please support Chacruna's work by donating to us. We are an independent organization and we offer free education and advocacy for psychedelic plant medicines. We are a team of dedicated volunteers!

Can you help Chacruna advance cultural understanding around these substances?