- Medicinal Abortions in Mexican History: Botanical Knowledge Retained - January 13, 2021

You might assume that medicinal contraceptives are recent products of modern western science. In fact, Indigenous healers and midwives in the Americas used botanical knowledge to provide women with abortifacients long before contact with Europeans. This post, which looks at instances of abortion in Mexican history, builds on Naomi Rendina’s January 6th post on whispered networks, and provides another example of the complicated ways that women have preserved knowledge of plant medicines through whispered networks.

“We know that some early plant medicines had both psychedelic and contraceptive or abortion-causing properties.”

While the remaining historical evidence does not always reveal the nature of the substances used by women healers, we know that some early plant medicines had both psychedelic and contraceptive or abortion-causing properties. Women’s carefully preserved and often concealed knowledge about these plants has been deeply contested in law and medicine, making it all the more important that we look back at how women participated in safeguarding information about botanical remedies in the past.

Mexican Abortion

In Mexico, midwives and healers continued using such knowledge during the colonial era and throughout the nineteenth century. While representatives of institutional medicine (professional organizations, faculty members, and public health agencies) often attempted to restrict the accessibility of these substances, there were also instances, especially in the nation’s geographical peripheries, in which physicians supported the work of unlicensed medical healers, which included women with plant-based knowledge.

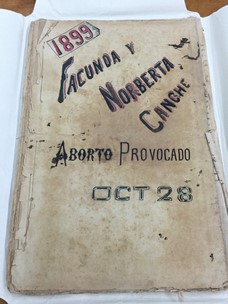

Let’s look at a couple of specific examples. A few years ago, when I was working in the state provincial archives of the Yucatán, on Mexico’s gulf coast, I came across a fascinating criminal trial for abortion. The elaborate cover page of the dossier was itself unusual in that, visually, it resembled a Broadway playbill (Facunda and Norberta Canche star in the new hit musical, “The Intentional Abortion”!)

The details of the case were also striking. In the city of Mérida in 1899, Facunda Canche, whose surname indicates she was Mayan, denounced her own 14-year-old daughter, Hermenegilda, to a local justice of the peace. Canche said her daughter had dishonored her by moving in with her suitor. Once apprehended, Hermenegilda counter-denounced her mother. Hermenegilda declared that her mother kept company with men other than her husband, and that this social disgrace had forced her to move into her suitor’s more respectable house. Further, Hermenegilda charged, after having discovered Hermenegilda was five months’ pregnant, Canche supplied her with a medicinal drink to provoke the miscarriage of her fetus. And so began a judicial inquiry into the details of the alleged abortion.

Join us at Sacred Plants in the Americas II

Medical Abortifacients

Under interrogation Facunda Canche and midwife Norberta Canche asserted they had not provided an abortifacient, but only a drink made with the “leaves of verbena” mixed with honey to treat an illness in Hermenegilda which they called “pasmo.” Verbena (also called verbain) is a genus in the Verbenacea family, which contains hundreds of species mainly native to the western hemisphere. Many species are now recognized for various medicinal properties. Although Juan Miró, a physician who provided expert medical opinion in the case, testified that verbena did not have abortifacient properties, current-day research identifies some species of verbena with just this attribute.

It seems that either Miró did not know or did not care that a midwife had supplied an abortifacient to a pregnant adolescent. Given that many of Miró’s contemporaries were denouncing the “criminal barbarism” of Indigenous midwives who provided pregnant women with such treatments, either explanation for his testimony is intriguing. In any case, his declarations sufficiently appeased the court, who convicted neither mother nor daughter with abortion.

“Some contemporary Mexicans may have considered abortion criminal or immoral, but everyone, even the state, understood that taking ‘regulators’ to provoke the onset of ‘suppressed menses’ was a perfectly acceptable practice.”

Miró related that the illness from which Hermenegilda suffered, pasmo, referred to the “absence of menstruation.” The idea of the routine “absence” or “suppression” of the menses caused by a condition other than pregnancy (for instance, anemia or malnutrition) was common in this era. Some contemporary Mexicans may have considered abortion criminal or immoral, but everyone, even the state, understood that taking “regulators” to provoke the onset of “suppressed menses” was a perfectly acceptable practice. Several researchers have suggested, however, that women who were shamefully pregnant, like those who were unmarried and likely to be judged harshly, might claim instead to be merely suffering from routine and respectable “menstrual suppression” in order to access medicinal abortifacients from midwives, healers, or unsuspecting or complicit physicians.

Contraceptive Potions

In a second contemporary case from Mérida, we find more evidence of physicians’ testimony supporting, rather than challenging, the lawfulness of unlicensed health care providers. Here two neighbors of a woman called Escolástica Alcocer announced they had spied the woman’s mother and brother burying the corpse of Alcocer’s newborn one night. Other neighbours came forward to declare that Alcocer’s mother had asked for several “potions” from a boticario (a pharmacist) that would provoke an abortion. A few days later, one José Jesús Cervesa, appeared, describing himself as a “mechanic who understands something of botany.” Cervesa was then an unlicensed pharmacist and thus a member of a group who, like midwives, the medical profession sought to regulate in the nineteenth century.

Discover Indigenous Reciprocity Initiative of the Americas

Cervesa testified that Alcocer and her mother had consulted with him for a cure for the absence of menstruation in the latter. He prescribed a medicine composed of saffron and “semen contra.” The latter was the common name for artemisia (or altamisa), a mild psychedelic plant that women in other locations in Mexico had traditionally used to provoke miscarriages, and one known to women in medieval Europe as mugwort, and used there for the same purposes. People also used mugwort around the world in rituals and ceremonies that cross different cultures and time periods.

“People also used mugwort around the world in rituals and ceremonies that cross different cultures and time periods.”

Both of these cases show unlicensed health care workers supplying clients with pre-contact botanical medicines, some of which share a direct lineage with psychedelic medicines, that women in the Yucatán took in the late nineteenth-century to limit reproduction. They also suggest that this knowledge was both hidden and coded for strategic use. These two cases of Mexican abortion were far from isolated incidents. We are now realizing the great extent of Mexican communities’ preservation of pre-Columbian botanical knowledge long after the end of the colonial era. Perhaps the next question to address is the extent to which professional medicine either remained ignorant of, tolerated, or in some cases even supported the circulation of this knowledge, which passed from mouth-to-mouth and hand-to-hand in communities in their midst, especially when those communities involved Indigenous people and women.

Art by Mariom Luna.

Take a minute to browse our stock:

Did you enjoy reading this article?

Please support Chacruna's work by donating to us. We are an independent organization and we offer free education and advocacy for psychedelic plant medicines. We are a team of dedicated volunteers!

Can you help Chacruna advance cultural understanding around these substances?