- Mazatec Shamanic Knowledge and Psilocybin Mushrooms - February 10, 2022

- Dream and Ecstasy in Mesoamerican Worldview: An Interview with Mercedes de la Garza - January 27, 2022

- María Sabina, Mushrooms, and Colonial Extractivism - May 27, 2021

Mazatec Shamanic Knowledge

The Mazatec people have been widely recognized for their ritual and therapeutic uses of psilocybin mushrooms, or ndi xijtho—“little ones that sprout.” These rituals are popularly known as veladas. They have been widely described in anthropological literature since the late 1950s, especially since the encounter between Maria Sabina and Robert Gordon Wasson in 1955, although the first studies by Blas Pablo Reko, Jean Bassett Johnson, Robert Weitlaner, and Richard Evans Schultes date from the late 1930s.

“THE DEITIES HAVE CHOSEN SHAMANS IN MESOAMERICA EITHER THROUGH DREAMS, INITIATION RITES, OR DUE TO AN UNEXPLAINED AND PERSISTENT ILLNESS.”

The specific knowledge of Mazatec shamans is neither unique nor new. Its roots extend to the ancient Mesoamerican tradition. For example, practices such as divination with corn kernels are recorded in 16th-century codices and remain present in other Indigenous practices today.

Left: Codex Borbonicus, plate 21. Right: Corn divination ritual, Huautla de Jiménez.

The deities have chosen shamans in Mesoamerica either through dreams, initiation rites, or due to an unexplained and persistent illness. The ability to heal and communicate with sacred entities is considered a granted gift and implies a permanent commitment to the community and the divinities. Among the Mazatec people, these wise people are the chjota chijne.

“To access knowledge and become a chjota chijne there are several paths that are experienced in three ways: being born with the gift, self-interest, and interest of a third party; in the latter case, the person can be chosen by a chjota chijne, by a principal being, or by the sacred mushrooms, popularly known as “holy children” (Rodriguez, 2018: 61).

“THE MAZATEC SHAMANS OR CHJOTA CHIJNE HAVE DISTINGUISHED THEMSELVES BY THE RITUAL USE OF VARIOUS PLANTS AND MUSHROOMS WITH PSYCHOACTIVE PROPERTIES.”

Communication and interaction between the chjota chijne and the “principal beings” or sacred entities occur through various types of ecstatic trance, such as fasting, self-sacrifice, or the use of plants, mushrooms, and animals with psychoactive properties.

Among the best known are the psilocybe mushrooms, popularly known also as “holy children,” the leaves of Salvia divinorum, also known as “Ska Pastora” or herb of the shepherdess, and the seeds of Rivea Corymbosa and Ipomoea violacea, popularly known as “Seeds of the Virgin” or Morning Glory.

In Mazatec shamanism psilocybe mushrooms, Morning Glory, and Sky Pastora hold especial significance. Left: Psilocybe caerulescens. Center: Ipomoea violacea. Right: Salvia divinorum.

The chjota chinej do not necessarily use all the plants mentioned above, depending on the patient’s illness, the time of the year when the plants are available, or the specialization that each shaman has. On this crucial matter, Maria Sabina mentions that:

“If I have a sick person in the time when mushrooms are not available, I resort to the leaves of the shepherdess. Ground and drunk, they work as holy children. Of course, the Pastora is not strong enough. There are other plants called ‘Seeds of the Virgin.’ The Virgin created these plants. I do not use the seeds, although some wise men use them” (Estrada, 2005: 78).

The Ecstatic Trance

The wisdom of the Mazatec shamans or chjota chinej lies in the knowledge of each of these plants’ properties and the different uses that each one has. Among the main uses are: 1) the therapeutic alleviation of an illness, 2) divination rituals to determine the whereabouts of a person, some stolen good, or even to interpret love, and 3) to seek advice concerning some problem or difficulty.

“IN THESE RITUALS, THE CHJOTA CHINEJ EXPERIENCES AN ECSTATIC TRANCE AND ENCOUNTERS THE SACRED ENTITIES.”

Each of these uses is part of a specific ritual called velada, which takes place at night and may be accompanied by chants and prayers. In these rituals, the chjota chinej experiences an ecstatic trance and encounters sacred entities or chikones, and dynamically interacts with them.

In general, there are three types of ecstatic trance: 1) the possession trance, which is when a sacred or “supernatural” entity takes over the soul or spirit of the individual and dominates one’s will and consciousness; the paradigm of this type of trance is what is popularly known as “demonic possession,” 2) the mediumistic trance, which is when a sacred or “supernatural” entity manifests itself through the body or language of an individual, some well-known examples are found in “spiritualism” and in the figure of the “rhapsodies,” and 3) the shamanic trance which is when the ritual specialist interacts, with the help of visionary plants and mushrooms, with the sacred entities, the ancestors, or the “spirits” of caves, mountains, rivers, lakes, and lagoons, this interaction with the sacred entities allows the chjota chinej to discover the origin of the illness and to relieve the patients.

“In the ritual, the wise Doña Teresa first consults the corn to obtain the necessary evidence with which she will act. She prays to Saint Martin Caballero, to Chicón-Nindo, the Supreme Lord of the Hills, the one who dominates all the hills in the Mazateca highlands, and to the volcanoes located in the “four corners of the world” to ask them to help her. Then she drops on a white cloth 33 grains of corn, chosen from an ear of 13 rows of seeds—these she blesses on the last night of the old year, according to the instructions she receives from the mushroom” (Fagetti, 2017:32).

Join us for our next conference!

Language and Mazatec Worldview

Language is a fundamental aspect of the shamanic trance. The chants, prayers, rogations, and prayers are what allow the chjota chinej to establish relationships and interact with the “principal beings” with the “owners of the hills” (chicones), or with the guardians of the rivers, caves, and springs. This ritual language can reach poetic levels and is composed of remarkable metaphors and images.

“I HAVE TALKED TO TIME, TIME IS A GIANT SNAKE, TIME IS LIKE A GIANT SNAKE… THAT BINDS PRESENT, PAST, AND FUTURE TIME.”

The sacred mushrooms express themselves through the shaman’s words. For instance, the chants of Maria Sabina, but there are other examples of this type of literary communication: “I have talked to time, time is a giant snake, time is like a giant snake, where I neither saw its head nor its tail, but I could talk, we could talk, it is a giant snake that binds present, past, and future time” (Heriberto Prado Pereda).

The personification and communication with sacred entities are some of the central features of the worldview of Indigenous peoples. Thus, it is necessary to take an ontological turn to better understand the sacred and ritual uses of psilocybin mushrooms. This ontological turn implies recognizing different ways of relating between human beings and nature, rather than from the paradigm that prevails in Western culture.

“BASED ON THE WORLDVIEW OF INDIGENOUS PEOPLES, MUSHROOMS SHOULD NOT BE CONSIDERED A DRUG OR PSYCHOACTIVE SUBSTANCE. BUT RATHER AS SACRED BEINGS OR ENTITIES WITH WHOM RECIPROCAL RELATIONSHIPS ARE ESTABLISHED.”

In the worldview of Mazatec peoples, the earth, the air, the mountains, the clouds, and the sacred mushrooms are entities endowed with life. A personality is attributed to the sacred mushrooms with which it is possible to establish communication through sacred and ritual language.

Based on the worldview of Mazatec peoples, mushrooms should not be considered a drug or psychoactive substance. But rather as sacred beings or entities with whom reciprocal relationships are established.

Mushrooms are not detached from the territory. They are an integral part of the sacred landscape. Finally, psilocybin mushrooms allow communication with ancestors and other “supernatural” or “extra-human” beings such as the chikones, i.e., guardians of the hills, caves, springs, or forests.

Mazatec Sacred Landscapes

In the Mazatec tradition, the chjota chinej hold veladas to know about the illness of their patients. These rituals contact various sacred entities such as the chikones, which are considered the guardians of different natural places. It is necessary to ingest sacred mushrooms. During the velada, chants and prayers are intoned. Various elements are used, including candles, incense or copal, aguardiente, cocoa, tobacco, flowers, and images of Catholic saints and the Virgin of Guadalupe.

“THE SHAMAN CAN DETERMINE WITH THE HELP OF SACRED MUSHROOMS IF A PERSON WILL HEAL OR NOT.”

Each shaman is in charge of preparing a “table,” where all the ritual elements are carefully arranged. This table represents spiritual geography that the shaman knows perfectly. Likewise, the mushrooms are smoked with copal smoke, which is a purification ritual, and then distributed in pairs among the evening participants.

During the ceremony, the shaman can invoke the ancestors to request their help and advice and the “Lord of the hills,” or the guardians of caves, rivers, and springs. It is considered that the chjota chinej can access the place where the souls of the deceased are. The shaman can determine with the help of sacred mushrooms if a person will heal or not. Sometimes, the chjota chinej can bring back the patient’s soul; it is also said that many snakes inhabit the place where the deceased are found. The chjota chinej also negotiates with the guardians of the hills as to whether the patient must pay an offering with candles, food, or an animal.

Mazatec shamanic knowledge extends its roots to the ancient Mesoamerican tradition. It has also incorporated symbols and elements from other religious traditions. Sacred mushrooms are even believed by some to be the blood of Christ or that it is the Virgin who indicates how to heal:

“The Virgin Mary and Jesus Christ are symbolic figures in the ecstatic experiences that Doña Teresa and her patients relate. They are summoned by the sacred mushroom, which serves as a facilitator of communication. With the crown on her head and covered with her mantle, the Virgin usually intervenes. She touches and presses the suffering part and guides the hand to teach how the healing should be done” (Fagetti, 2017: 32).

“THIS SPIRITUAL SYNERGY SERVES AS AN EFFECTIVE ANTIDOTE AGAINST ORTHODOXY AND DOGMATIC THINKING.”

Mazatec shamanism brings together a series of features from the ancient Mesoamerican tradition such as 1) the use of plants and mushrooms with psychoactive properties, 2) divination rituals with corn kernels, 3) communication through ritual language with the guardians of the hills, rivers, caves, and lagoons 4) the tradition of distributing mushrooms in pairs, based on the notion of the primordial couple, 5) the “diet” or abstinence from eating certain kinds of food and from having sexual relations before and after the ceremonies.

All these features converge in a spiritual synergy that configures the sacred landscape with elements coming from Catholicism such as Jesus Christ, the Virgin, and the saints St. Peter and St. Paul. This spiritual synergy serves as an effective antidote against orthodoxy and dogmatic thinking since this coexistence of elements is controversial for some sectors within Catholicism.

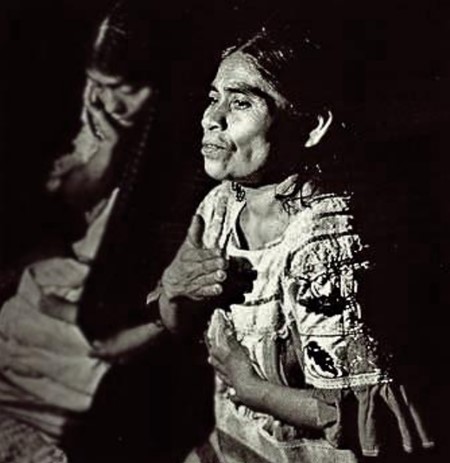

María Sabina in front of a “ritual table.”

The conjunction of these symbols is only a fragment of the complexity and cultural richness surrounding these ceremonies. The veladas and ritual use of plants and mushrooms with visionary properties must be considered a source of wisdom and an expression of the shamanic knowledge of the Mazatec people.

Art by Fernanda Cervantes.

Discover the Indigenous Reciprocity Initiative of the Americas

References

Bassett Johnson, Jean (1939). “The Elements of Mazatec Witchcraft”. Etnologiska Studier, Vol. 9, pp 128-150.

De la Garza, Mercedes (1990) Sueño y alucinación en el mundo náhuatl y maya. México, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.

Estrada, Álvaro (2005 [1977]) María Sabina, la sabia de los hongos. México, Editorial Siglo XXI.

Escohotado, Antonio (1999) Historia General de las Drogas. Madrid, Espasa-Calpe.

Fagetti, Antonella (2017). “Nocturnal Journeys: The Sacred Plants of the Mazatecs”. Revista Artes de México. Número 127. Diciembre, pp 28-36.

García Flores, Inti (2020, November 12). “Niños Santos, Psilocybin Mushrooms and the Psychedelic Renaissance.” Chacruna.net https://chacruna.net/mazatec_mushroom_ceremony_psychedelic_tourism/

González, Osiris (2021 May 27). “María Sabina, Mushrooms and Colonial Extractivism”. Chacruna.net https://chacruna.net/maria-sabina-mushrooms-and-colonial-extractivism/

Rodríguez, Citlali (2019). Mazatecos, niños santos y güeros en Huautla de Jiménez. México, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.

Piña, Saraí (2021) Siguiendo al hongo mágico y la utopía psicodélica. Entre la mercantilización y la medicalización de hongos psilocibes. México. Centro de Investigaciones y Estudios Superiores en Antropología Social (Tesis de Maestría).

Schultes, Richard Evans (1939) “Plantae Mexicanae II”. Botanical Museum Leaflets, Harvard University, February 21, 1939, Vol. 7, No. 3 (February 21), pp. 37-56.

Take a minute to browse our stock:

Did you enjoy reading this article?

Please support Chacruna's work by donating to us. We are an independent organization and we offer free education and advocacy for psychedelic plant medicines. We are a team of dedicated volunteers!

Can you help Chacruna advance cultural understanding around these substances?