- Introduction to Women and Psychedelics - July 26, 2024

- Global History of Psychedelics: A Chacruna Series - October 4, 2023

- Can Psychedelics Promote Social Justice and Change the World? - August 30, 2021

Kiyoshi Izumi was born in 1921 in Vancouver, British Columbia. He is a vital figure in the history of psychedelics as an influential and decorated architect who courageously took on governments and hospital superintendents arguing that institutional spaces aggravated mental illnesses rather than helping to soothe them. He arrived at these conclusions in part due to his own experiences taking LSD and observing hospital conditions. He fundamentally believed that by taking LSD he could generate meaningful insights into the design of institutional spaces. But in many ways his legacy is a testament to the Japanese Canadian community’s resilience in the face of racist policies and the equally persistent support from his wife, Amy (Nomura) Izumi.

Kiyoshi Izumi’s “legacy is a testament to the Japanese Canadian community’s resilience in the face of racist policies and the equally persistent support from his wife, Amy (Nomura) Izumi.”

Kiyoshi’s parents, Tojiro and Kin were born in Japan and came to Canada as immigrants before their son was born. By the time Kiyoshi Izumi entered his 20s, it was not a good time to be a Japanese Canadian. In December 1941 the bombing of Pearl Harbor by Japan triggered a military response that not only brought the US into the Second World War but also unleashed a series of anti-Japanese policies there and in Canada. Both nations restricted the movements and freedoms of people of Japanese descent and set up internment camps in isolated, interior regions. Japanese immigrants, as well as naturalized citizens, were confined behind fences and designated as enemy aliens.

As the Canadian government established internment camps and seized Japanese property and businesses, Kiyoshi went east. He ultimately escaped to Saskatchewan where fewer than 100 Japanese Canadians lived at this time. Unlike its neighbouring provinces of Alberta and Manitoba, Saskatchewan did not enter into a formal agreement with the federal government to place Japanese Canadian families on farms or in factories during the Second World War. Despite what might appear to be a relatively less racist context, most Japanese businesses in Saskatchewan changed their names at this time, in the hopes that they would not be associated with the Japanese enemy. At 22-years-old Kiyoshi enrolled in school in Regina, Saskatchewan and, like all Japanese people in Saskatchewan at this time, submitted monthly reports to local police about his actions and whereabouts.

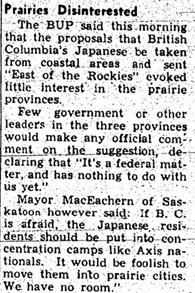

To say that this was a restrictive environment is an understatement. Historian Patricia Roy explains that every Japanese person seeking residence in Saskatchewan had to appeal directly to the premier, and despite Kiyoshi’s excellent academic record and acceptance into universities, he was not permitted to live in Saskatoon. In January 1942, The New Canadian, the Japanese Canadian newspaper, reported that the Saskatoon mayor said “… the Japanese residents should be put into concentration camps … It would be foolish to move them into prairie cities. We have no room.” This ethnic exclusion in the city of Saskatoon meant that Kiyoshi Izumi was not able to attend the University of Saskatchewan. In 1944 he left Regina to attend the University of Manitoba’s School of Architecture from 1944-1948.

One of the blank spots in Kiyoshi’s biography is how he came to stay in Regina, and how this young Japanese Canadian managed to convince authorities that he could find accommodations and live safely in such a hostile environment. The answer may lie in the story of his wife, Amy.

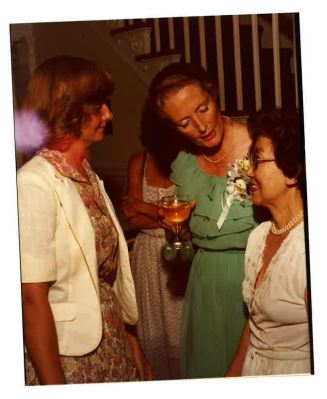

In 2003, I (Erika Dyck) interviewed Amy Izumi, wife of the famous architect who took LSD and inspired patient-centred designs, such as the socio-petal concept that supported social engagement among patients. Amy proudly showed me around her seniors’ complex where she lived, a building that her husband, Kiyo, as she called him, had helped to design. It featured comfortable private living spaces with a Japanese garden in the centre of the complex. We spoke about his work. We drank tea and poured over photographs of their family, vacations, and their life together. Kiyo died in 1996, and while his records can be found in libraries and archives, these intimate stories are always valuable additions.

I asked Amy how they met. She closed the photo album and asked me what I knew about the Second World War. She explained that being Japanese in Canada as a young woman was difficult. Her father had operated a business in Regina, but they had to change its name and lost a lot of customers during this period. She remembered Kiyoshi coming to her father’s business, seeking refuge, even a job. Her father took him in, and while Amy did not know for sure, he may have even later claimed that Kiyoshi was kin in order to protect him from persecution or even deportment. He came to live with the Nomuras and was one of at least ten Japanese students to attended Regina College in the 1940s. When Amy’s brother and father joined the Regina Nisei Club, to support Japanese families in the region, Kiyoshi Izumi became a member, and remains an honoured member of this organization.

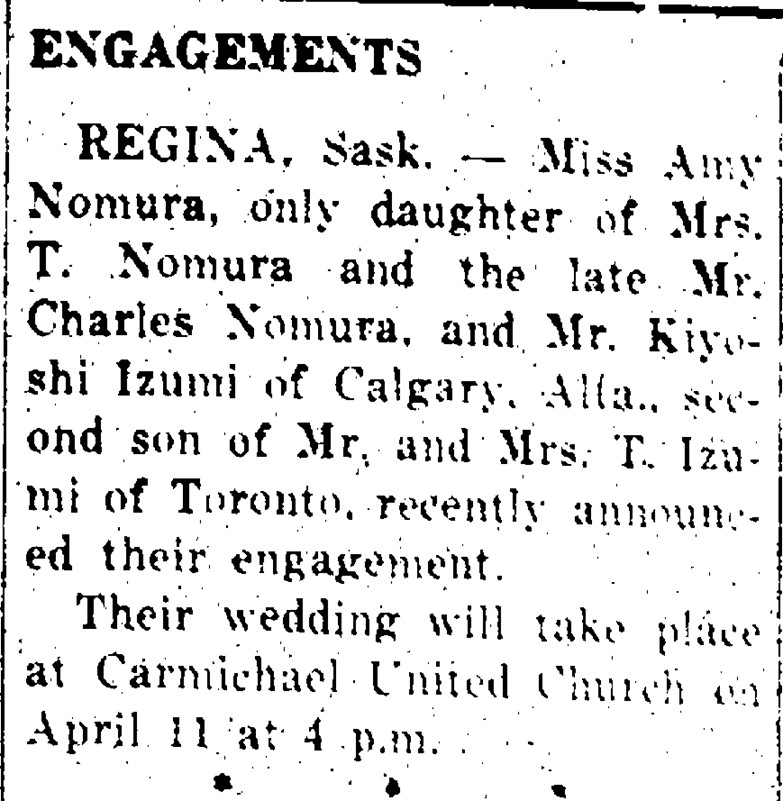

In 1950 Amy and Kiyoshi announced their engagement. By this time, Kiyoshi had completed his degree in architecture in the neighbouring province of Manitoba. He returned to Saskatchewan to the Nomura family and joined one of his former classmates from Regina, James Sugiyama, and one from Winnipeg, Gordon Arnott, in opening the Izumi, Arnott, and Sugiyama architectural firm.

A few years later, Kiyoshi, who now went by the name Joe, was invited to the Saskatchewan Mental Hospital at Weyburn. Humphry Osmond invited Joe to participate in the psychedelic research, and to seek his advice as an architect about how to think about healing spaces from the perspective of patients. Joe and Amy drove from Regina to Weyburn and were hosted by Jane and Humphry. Amy remembered being in their home and agreeing to try LSD together with the Osmond’s to see whether it might help Joe in his work.

Discover Indigenous Reciprocity Initiative of the Americas

For Amy, the experience was not altogether pleasant. She felt nauseous and disoriented. Humphry gave her something else, which she later thought might be niacin, because of the research groups tendency to use niacin to reduce hallucinogenic effects. Joe, though, marvelled at his ability to see more clearly, to hear despite being deaf in one ear, and to really see spaces differently. It opened his mind to new possibilities. But, having just met the doctor and his wife, Joe was reluctant to reveal these insights and concerned about what effects the drugs were having on his mind. He stayed quiet.

Amy explained to me that Joe later opened up to her. He wasn’t sure that it was safe to explore the experience fully, and wanted to first share his thoughts with Amy before returning to the British doctor. Amy helped him put his thoughts into words, and coaxed him through his experience—both during the LSD session, and for several days after—as he worked through its meaning for him. Amy and Jane, however, had also connected during this dinner.

Joe and Humphry also soon became fast friends. Joe was hired to do an architectural assessment of the old-style asylum, and to recommend better hospital designs based on his experiences interpreting space under the influence of LSD. While these two worked on hospital reforms, Jane and Amy became close friends. Perhaps they shared some common feelings as outsiders in a small prairie region, despite the vast differences in Jane’s British upbringing, and Amy’s Japanese-Canadian experiences.

Over time the families grew close. They spent holidays together. They shared dinners, attended social functions together, and opened each other to new networks of thinkers. Amy and Joe continued to participate at the Nisei Centre in Regina, supporting Japanese Canadians as they worked to rebuild their cultural centres after the Second World War. When Jane was pregnant with her second daughter, Amy was chosen as the godmother.

“The quiet, steady, and sensitive ways that Jane and Amy formed relationships helped to create a supportive environment for psychedelic experimentation that opened new avenues for research.”

These intimate family connections and networks are not often the stuff of history books, and they tend not to make the headlines when we think of great achievements or celebrated moments. But the quiet, steady, and sensitive ways that Jane and Amy formed relationships helped to create a supportive environment for psychedelic experimentation that opened new avenues for research.

At a time when hostility towards Japanese people in North America had reached a fever pitch, families were under tremendous pressure to find ways of avoiding detection and internment. The story of Amy and Kiyoshi is a story of resilience, friendship, but also trauma and healing. We are grateful that Amy opened her home to allow us to share it here as a reminder of the many ways that people came together in pursuit of a psychedelic future.

Recordings are now available to watch here.

Art by Mariom Luna.

Take a minute to browse our stock:

Did you enjoy reading this article?

Please support Chacruna's work by donating to us. We are an independent organization and we offer free education and advocacy for psychedelic plant medicines. We are a team of dedicated volunteers!

Can you help Chacruna advance cultural understanding around these substances?