- Introduction to Women and Psychedelics - July 26, 2024

- A Bridge Between Two Worlds: Ayahuasca and Intercultural Medicine – Interview with Anja Loizaga-Velder - May 18, 2022

- “It is not an orthodox psychotherapy”: An Interview with Ivonne Roquet, Daughter of a Psychedelic Pioneer in Mexico - February 22, 2022

It is undeniable that we are going through a new era that the English-speaking media has frequently called the “psychedelic renaissance.” There is a constant increase in the study and research (mainly biomedical) into the potential roles of psychedelic substances as future therapeutic promises that could change the paradigms in psychiatry and psychology. However, the historical prohibitions on consciousness-raising substances has blocked this research for decades, and particularly so in Mexico and Latin America. The development of scientific research and therapeutic applications with these substances has been a task that has been considerably obstructed due to the current prohibitionist paradigm and the stigma and taboo from which society and culture usually approach the phenomenon of states of consciousness. Despite these restrictions, recent efforts to decriminalize psychedelic plants, including mushrooms, is opening up new possibilities for developing scientific research and introducing therapeutic applications.

At first glance, it seems that Mexico, with all its psychedelic pharmacopeia and inherited knowledge from Indigenous cultures, has been at a standstill in comparison with other countries that are working with local plants and compounds. However, this initial perception is incorrect. In fact, at the beginning of the 19th century and into the 20th century there were a number of Mexican scientists who regularly studied the chemical and therapeutic properties that these plants, including mushrooms and cacti, had to offer.

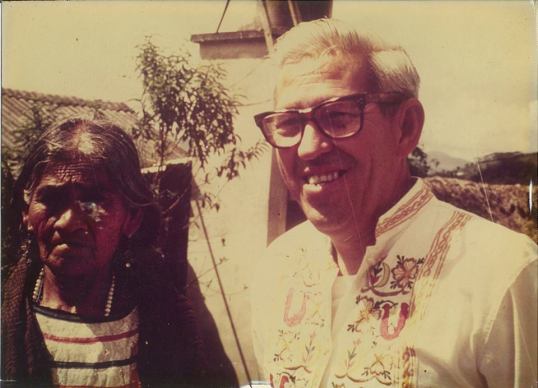

Among these pioneering scientists is Dr. Salvador Roquet (1920-1995). Roquet’s work remains avant-garde. He integrated a great part of the traditional Indigenous knowledge on using these plants with western disciplines such as psychoanalysis and neuropharmacology. He met and collaborated with scientists and key figures of the time, from the Mazatec shaman María Sabina, the American countercultural icon Timothy Leary, and even the discoverer of LSD himself, Albert Hofmann, or the father of transpersonal psychology, Stanislav Grof. Grof credits his encounter with Roquet in 1972 for introducing him to the therapeutic potentials of ketamine (a powerful dissociative anesthetic). Clearly, by then, Roquet was already using ketamine and other substances (natural and synthetic) as part of the wide range of tools that his psychotherapeutic method (“Psychosynthesis”) gave him. Following this methodology, Roquet exposed his patients to audiovisual stimuli in order to catalyze profound experiences, such as the dissolution of ego.

In order to better understand this history, I spoke with Ivonne Roquet. She is a doctor specializing in acupuncture and the Diagnonis, Sensitive, Tactile (DST) system developed by Mexican acupuncturist Dr. Guillermo ley Hurtado. Besides being a thanatologist and psychotherapist (specialized in the psychosynthesis of Salvador Roquet), Ivonne is Salvador’s daughter, and someone who inherited the theoretical knowledge of her father’s research. She shared meaningful experiences with him. Because of this, no one is better than her to know this history and its implications.

How old were you when you had your first contact with the work of your father, Dr. Salvador Roquet, with sacred plants?

My first contact with these sacred plants happened when I was approximately 12–13 years old, when my father, Dr. Salvador Roquet, had his office in the streets of Monterrey, in the Roma neighborhood in Mexico City. In this space, he performed psychoactive therapies with the patients he had to psychoanalyze. Later, I had the opportunity to go with him to Huautla de Jimenez, Oaxaca, Mexico, where I witnessed a ceremony performed by María Sabina, where my father included his patients.

As a witness of these moments, what can you tell us about the development of the psychosynthesis method?

Everything started through an experience that he had in 1957, when he participated as the “guinea pig,” as he used to say. In that experience, they applied mescaline intravenously. It was a tough but important experience because he saw he could help his patients. Because he lived with all this experience, he had a jolt. He realized the richness of these substances to help integrate the subject’s personality.

This was his first contact with hallucinogens. Subsequently, after some time, about ten years, when he was traveling in Paris. He saw a book from Roger Heim when he was in front of a library. That is when he had this insight and decided that the best way to know and apply these substances was going to the origin of things, and why not, since these plants were in his own country. He contacted the Indigenous community, especially María Sabina, the shaman who worked with mushrooms at the time. He had to know and experience for himself how that knowledge applied to his technique: psychosynthesis.

“PSYCHOSYNTHESIS HAS DUAL SOURCES: PSYCHIATRIC ACADEMIC EDUCATION AND THE INDIGENOUS PEOPLES’ EXPERIENCE.”

Could you tell us more about this theory?

Psychosynthesis has dual sources: psychiatric academic education and the Indigenous peoples’ experience. It is there that he created all this methodology because, in the beginning, he did not know the plants, the doses, or how to guide a session or experience of this nature. In other words, he had to go to the source to access this knowledge. It was not enough with the academic-psychiatric training. He wanted to go above and beyond because he knew it was a profound experience. He knew that these experiences helped treat a pathology, but they also helped mind and spirit.

Join us for our next conference!

How did knowing this influence you on a personal and professional level?

This approach influenced my career to the level that I decided to study medicine. Not only because of the use of sacred plants but also because of the implications of being a social doctor at that time (late 1960s and early 1970s). I knew my Mexican roots, the contact with my land, the relation with our Indigenous brothers, the clothing from the Indigenous cultures, the respect, the community service, and the relationship between doctor-patient without borders through my dad’s work. These are just a few of the many things that I learned during the years that I had contact with the Mexican cultures that used sacred plants.

Professionally, it helped me understand social service, that we should not arrive like conquerors to these communities just because we are the doctors in charge of the health centers. On the contrary, we must be one with the people, learn from others. And if they allow it, contribute with our knowledge, and give good service as a doctor.

“PROFESSIONALLY, IT HELPED ME UNDERSTAND SOCIAL SERVICE, THAT WE SHOULD NOT ARRIVE LIKE CONQUERORS TO THESE COMMUNITIES JUST BECAUSE WE ARE THE DOCTORS IN CHARGE OF THE HEALTH CENTERS.”

As a doctor, have you been able to apply some of the principles of psychosynthesis with your patients? If that is the case, what have you observed?

We must clarify that psychosynthesis is not limited to the use of plants or psychoactive substances. On the contrary it expresses human knowledge without borders. This vulnerable “I” works after an experience with or without substances. In this way, the knowledge that I acquired seeing the patients in this state allowed me, foremost, to empathize with them. I saw their response to love, one of psychosynthesis’s main principles of personality theory.

What do you consider to be psychosynthesis’s main contribution to psychotherapy?

The use of natural psychodysleptic substances reduce the time of psychoanalysis. Another contribution is the creation of a profound humanistic psychotherapy with all its techniques based on Roquet’s personality theory of psychosynthesis (with and without substances). Actually, the theory given the name ‘psychosynthesis’ emerged in a conversation between Roquet and his colleague Dr. Robert Schirokauer Hartman (1910-1973), who told him ‘What you are doing is not an orthodox psychotherapy.’ In other words, he realized that Roquet was pushing boundaries; he was doing something else.

Broadly speaking, how did these psychosynthesis sessions work?

We go through different stages under the influence of these substances. The first stage is when you drink the substance that lasts approximately half an hour to take effect. In that stage, there is only fear and anticipation about what is going to happen. You could have psychosomatic effects, but it is not the actual effect. The second stage is when the substance is in the bloodstream and crosses the blood-brain barrier, and is in in the cortical portion or the synapses of the neurons, that is when the substance starts showing all its effects. Still, it is a stage where you can hallucinate and feel good. The hippies looked for this stage during the 1960s because it is a fantasy phase. After the subconscious flourishes in the third stage, you face experimental situations. It is a challenging stage because it is where you do not want to go, maybe because you do not like what you see, or you cannot handle it. Then, the fourth, you could get into madness. It is a stage that could put the patient in a psychotic state, and you could get into madness or have a mystical experience.

In a nutshell, his contribution is this methodology, but especially ensuring that the patient goes quickly to the fourth stage. Because he wanted the patient to confront the subconscious, these substances disintegrate the mind and personality, allowing the next stage, which is making a synthesis, to reintegrate everything that is fragmented, that is the contribution from psychosynthesis. On the other hand, the second part employed a technique like dream interpretation. He created a method to interpret the projective drawings that patients made during the sessions. It is a methodology and a process that, despite the years that have passed, is still valid. It is a shame that it will not continue because this is important for new generations.

What can you share about the reception of your father’s technique in his field? How did he experience that part?

It was not easy initially because of all the jealousy and selfishness. In other words, the psychiatric community was against him because his technique shortened the time of psychoanalysis. Besides, the use of hallucinogens was not legal. He went to prison, and it was a tough time because he could not continue with his research. When he got out of prison (because there was no reason to be inside), he created another technique without hallucinogens. The therapeutical cohabitation involved three intensive days of therapy.

Discover the Indigenous Reciprocity Initiative of the Americas

Did he work again with these plants and substances?

The truth is that he continued working as they said, “under the table,” it was something that he owned. He could not stop something that he created (his method) and knew that it had good results because he worked with schizophrenia and psychosis (what they call “the bad trip”). Well, Roquet recovered many people from those bad trips.

Knowing first-hand how your father’s work was rejected by the medical community at the time. What do you think about the current boom in clinical research with psychedelics?

I think there has been a lot of ignorance and lack of awareness. From my point of view, we had to learn to work as a team, we must make a real change to take advantage of the new knowledge and achieve an opening for the clinical use of psychodysleptics.

“FROM MY POINT OF VIEW, WE HAD TO LEARN TO WORK AS A TEAM, WE MUST MAKE A REAL CHANGE TO TAKE ADVANTAGE OF THE NEW KNOWLEDGE AND ACHIEVE AN OPENING FOR THE CLINICAL USE OF PSYCHODYSLEPTICS.”

As a woman and researcher interested in the clinical potential and therapeutic applications of these plants and substances, have you faced any professional difficulties during your career?

Solely for being a woman, no. The main problem has been using the plants and psycholeptics substances and the bad reputation around Roquet in his time. Prohibition and conservative visions have held back research for decades, and they have put behind bars several serious researchers who had much to contribute to this field.

Do you feel that as further advances in psychedelic research occur, your father’s work will be vindicated?

I do not feel that my father’s job needs vindication. His work speaks for itself. The advances in research with psychoactive substances should help support the use of sacred plants and their synthetic derivatives, as well as support that the scientific community accepts its use. To its legalization and widespread experimentation in favor of health and wellbeing.

What would you recommend to the new generations of researchers dedicated to the study and analysis of the ritual and therapeutic uses of the sacred plants?

First, an open mind and respect to the communities and entheogenic cultures, know your place, and understand that we are not healers or shamans. We could complement our scientific knowledge with these substances and make proper use of them to improve mental health.

This text was originally published in Spanish on Chacruna Latinoamérica, “‘No es una psicoterapia ortodoxa’: Entrevista a Ivonne Roquet, hija de un pionero psicodélico en México.”

Notes

1 Diagnosis, Sensitive, Tactile: It consists of making the diagnosis through the auricle, in traditional Chinese acupuncture, it is done through the pulses and the tongue.

2 Dr. Guillermo Ley Hurtado (Mexico). Medical surgeon graduated (UNAM) with postgraduate studies in Traditional Chinese Medicine.

Take a minute to browse our stock:

Did you enjoy reading this article?

Please support Chacruna's work by donating to us. We are an independent organization and we offer free education and advocacy for psychedelic plant medicines. We are a team of dedicated volunteers!

Can you help Chacruna advance cultural understanding around these substances?