- 2024 Begins with Trepidation in Psychedelic Medicine and Markets - January 26, 2024

- This is How Jurema, a DMT-Containing Tree, Helped the Pankararé People Recover Their Land in Brazil - December 29, 2023

- The Triumphant Comeback of Psychedelics - July 24, 2023

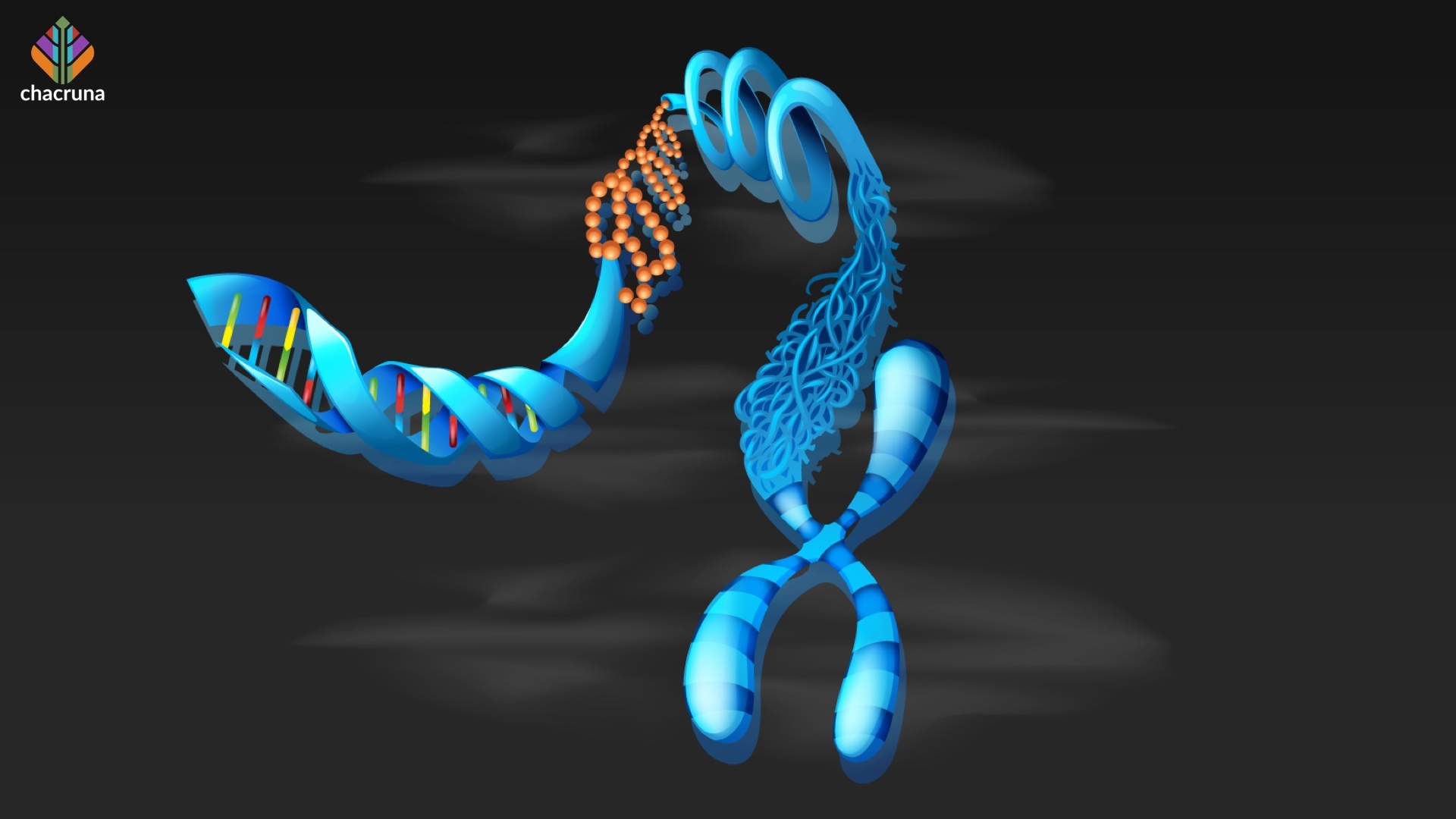

DNA confirms lineages known to traditional users that might be different species

Without the mariri vine, Banisteriopsis caapi, there is no psychedelic ayahuasca. Also known as daime and hoasca, the brew is obtained by cooking together leaves of the chacruna shrub (Psychotria viridis) with fibers of mariri, whose scientific name is supposed to designate a single species, but recent genetic studies suggest there might be more than one.

Any variety of mariri can provide the beta-carbolines that inhibit the monoamine-oxidase (MAO), an enzyme that prevents chacruna’s psychoactive effects by degrading DMT in the digestive tract. With the inhibitor in the vine ingested at the same time, DMT reaches blood circulation and the brain, resulting in the mirações (visions) that are characteristic of ayahuasca.

União do Vegetal (UDV) is one of the main ayahuasca religions in Brazil, besides Santo Daime and Barquinha. Its members recognize and grow at least three vine lineages, also known as ethnovarieties: tucunacá, caupuri, and pajezinho. This form of traditional knowledge has now been corroborated by analyzing DNA genetic markers.

UDV members recognize and grow at least three vine lineages, also known as ethnovarieties: tucunacá, caupuri, and pajezinho. This form of traditional knowledge has now been corroborated by analyzing DNA genetic markers.

The confirmation came as a result of Thalita Zanquetta Luz’s master’s dissertation at the National Institute of Amazon Research (INPA, in its Portuguese acronym). The first chapter in the dissertation was published in December by the journal Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution under the title “First DNA barcode efficiency assessment for an important ingredient in the Amazonian ayahuasca tea: mariri/jagube, Banisteriopsis (Malpighiaceae).”

Such a lengthy and technical title is certain to repel laypersons, but it refers to the discovery that different varieties of ayahuasca can be identified by looking for small sequences of DNA in the mariri vine (sometimes called jagube or yage). The “barcode” in this case is a metaphor for DNA markers that distinguish one organism from another.

Luz, who is the first author of the paper, received the suggestion for the subject of her master’s thesis from Antonio Saulo Cunha-Machado, a geneticist who is also a UDV member in Manaus. He had intended to study mariri during his own masters and PhD programs, but wasn’t able to secure the necessary funds in time to fulfill his plans.

Cunha-Machado ended up researching the surubim catfish with the fish geneticist Jacqueline Silva Batista, third and senior author of the article, but he never gave up on mariri. He succeeded in convincing his mentor to venture into plant genetics and to seek UDV’s support for the study, with the church providing not only part of the funds, but also 120 vine samples from four Brazilian states (Acre, Amazonas, Pará, and Rondônia).

Discover the Indigenous Reciprocity Initiative of the Americas

The thesis’s first chapter, published in the journal, analyzed 20 of the samples. Luz tested the barcoding potential of various DNA sequence types, concluding that the most efficient ones were “internal transcripted spacers” (ITS).

ITS belong to a wide modality of DNA stretches with no obvious function that appear interspersed in between genes (sequences that codify for proteins). Lacking a better analogy, they can be thought of as similar to the words “like” or “well,” which are frequently included in speech, but can be excised from a transcription without altering the general meaning.

Small ITS sequences floating in the vine genome’s ocean of DNA proved capable of discriminating the ethnovarieties tucunacá, caupuri and pajezinho, much like barcodes can identify each and every product on a supermarket shelf. Moreover, with help of these and other genetic markers, INPA’s researchers were able to single out a total of 12 different mariri lineages in those three big groups (clades).

In order to obtain the important ingredient in ayahuasca, UDV members grow the varieties by means of vegetative propagation, in this case planting stakes that produce new roots. One can use seeds, as well, but it isn’t easy to collect them from a plant that blooms quite a few meters from the ground—if the bloom is to be noticed at all.

“Vegetative propagation makes way for conservation measures that are more easily implemented, provided that genetic varieties have been properly identified in order to render those measures more effective,” explains Cunha-Machado.

“[Now] the methods described in the paper make genetic analyses possible, so that one can identify the different lineages and resort to propagation, therefore contributing to conservation,” he continues.

Thalita Luz, the student who ended up becoming a UDV member and attending services for a year, goes beyond and indicates possible impacts in the clinical domain, as well. After all, ayahuasca and DMT have shown good preliminary results as experimental therapies for depression.

She thinks that when one considers that varieties might cause distinct effects upon ingestion of the brew prepared with each of them, it becomes interesting to distinguish the vines in order to learn how their psychoactive components may vary. “This can make a difference in clinical trials,” she contends.

“We have just begun to decipher [mariri’s mystery],” says senior author Jacqueline Batista. “It’s been an interesting departing point confirming what was already phenotypically known. We need more studies and information to define, way down the road, if those are different species or what.”

“There are strong indications that there might be distinct species. We’ve found up to 28% of genetic distance [between vine varieties].”

Antonio Saulo Cunha-Machado

Cunha-Machado thinks the same way: “There are strong indications that there might be distinct species. We’ve found up to 28% of genetic distance [between vine varieties].”

Although members of ayahuasca churches do ascribe slightly different psychoactive effects to mariri varieties, until now nobody had investigated whether there is genetic diversity between the lineages, points out Francisco Prosdocimi, a biologist at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ), in appreciation of INPA’s research.

“Both caupuri varieties, with and without nodes, group together [in the same clade], which appears to suggest that the presence of nodes in this ethnovariety is possibly related to environmental factors rather than to genetics,” he points out.

Prosdocimi is a partner of Alessandro Varani, from UNESP’s School of Agricultural and Veterinary Sciences in Jaboticabal, in a project to sequence the whole genome (not only markers) of both the mariri vine (tucunacá and caupuri) and the chacruna shrub.

“One hopes for more mariri varieties to be collected and analyzed, so that we can pinpoint places with the highest genetic diversity in the vine, understand their biogeographical routes and maybe find this master plant’s point of origin,” proposes Prosdocimi.

“One hopes for more mariri varieties to be collected and analyzed, so that we can pinpoint places with the highest genetic diversity in the vine, understand their biogeographical routes and maybe find this master plant’s point of origin.”

Francisco Prosdocimi

So far, he and Varani have completed half of chacruna’s genome sequencing and a quarter of the vine’s, to be followed by annotation and fine analyses. The project is now ready to proceed at full speed, as they have secured the necessary funds from São Paulo State science foundation FAPESP. They are also keen to solve the mystery around mariri ethnovarieties.

Prosdocimi and Varani say that the research project is intended to follow the principles of respecting, promoting, and understanding Amazon Indigenous cultures, as well as fostering an alliance between Amerindian traditional knowledge and scientific culture.

“We hope to generate new genomic, evolutionary and functional information about the two plants that, in spite of belonging to our [Brazil’s] biodiversity, have been scarcely investigated under a molecular, genomic and taxonomic point of view,” states the approved project’s summary.

Cunha-Machado, UDV member who instigated Luz’s research with the vine, has a similar opinion: “Traditional knowledge does need more respect and attention. In our work we succeeded in documenting and demonstrating the importance of this knowledge.”

“Traditional knowledge and scientific knowledge are independent from each other, both are equally important, and I don’t believe one needs to get the seal of approval from the other,” says Cunha-Machado.

Note:

Originally published in Portuguese by Folha de São Paulo on the blog Virada Psicodélica HERE.

Art by Luana Lourenço.

Take a minute to browse our stock:

Did you enjoy reading this article?

Please support Chacruna's work by donating to us. We are an independent organization and we offer free education and advocacy for psychedelic plant medicines. We are a team of dedicated volunteers!

Can you help Chacruna advance cultural understanding around these substances?