- Gurus Behaving Badly: Anaïs Nin’s Diary & the Value of Gossip - March 10, 2021

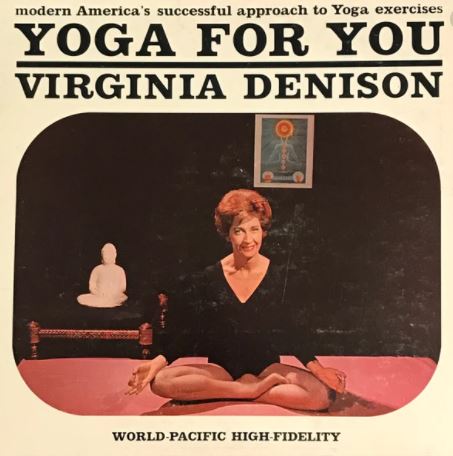

This is a story about Angela Anaïs Juana Antolina Rosa Edelmira Nin y Culmell, who wanted us to know that she did not care for Timothy Leary. As far as she was concerned, Leary wasn’t in or of the world and so he had no feel for people. When her dear friend Virginia Denison’s husband was in Europe, Virginia’s lover André came over and found her in bed with Leary. André proceeded to beat the yogini, breaking mirrors and chairs and pottery, screaming wildly. He threw a bottle through a window. Slapped her. Proposed to her. Stormed out in a huff. The episode was troubling enough that the writer set it down in her diary multiple times, trying to get it just right. There’s one detail that always stays the same, though. It’s how you know it was the point. The point, for Angela Anaïs Juana Antolina Rosa Edelmira Nin y Culmell—or Anaïs Nin, for simplicity’s sake—was Leary. He’d taken his hearing aids out the night before and he slept through the whole thing. The point was that he was a shitty lover, walled off from others. Oblivious. She could tell as soon as she met him. The Denison affair just cemented what Anaïs already knew with that uncanny writerly insight she liked to brag so much about. But this story is not about Timothy Leary. It is about the role of expertise and truth in American politics.

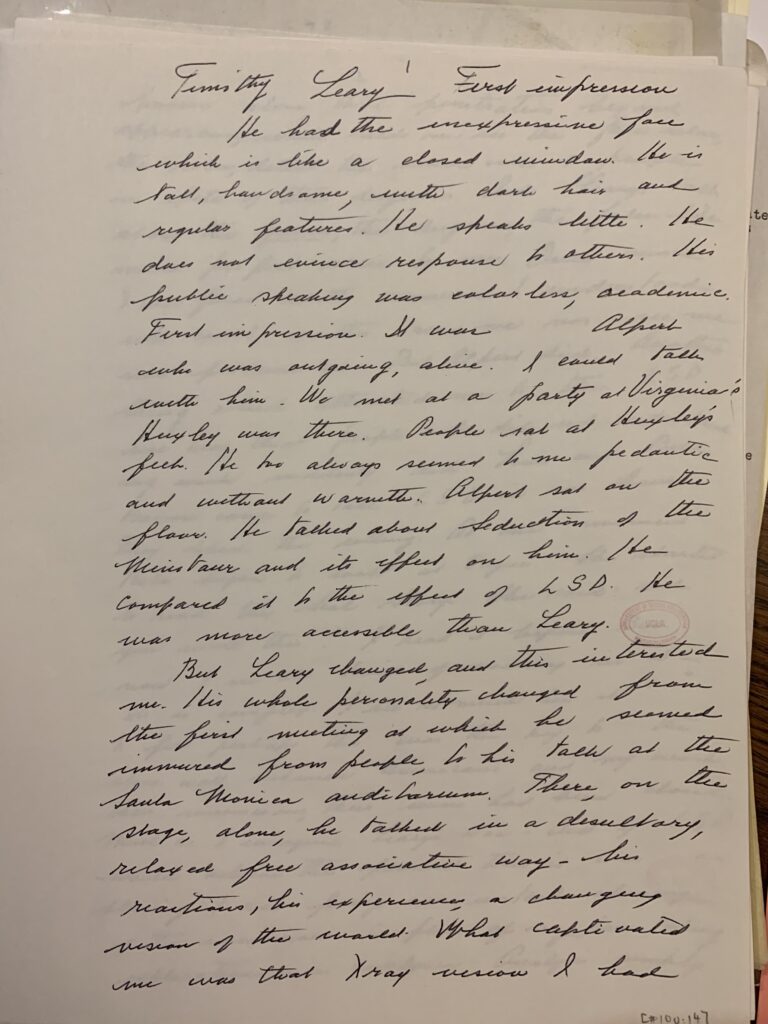

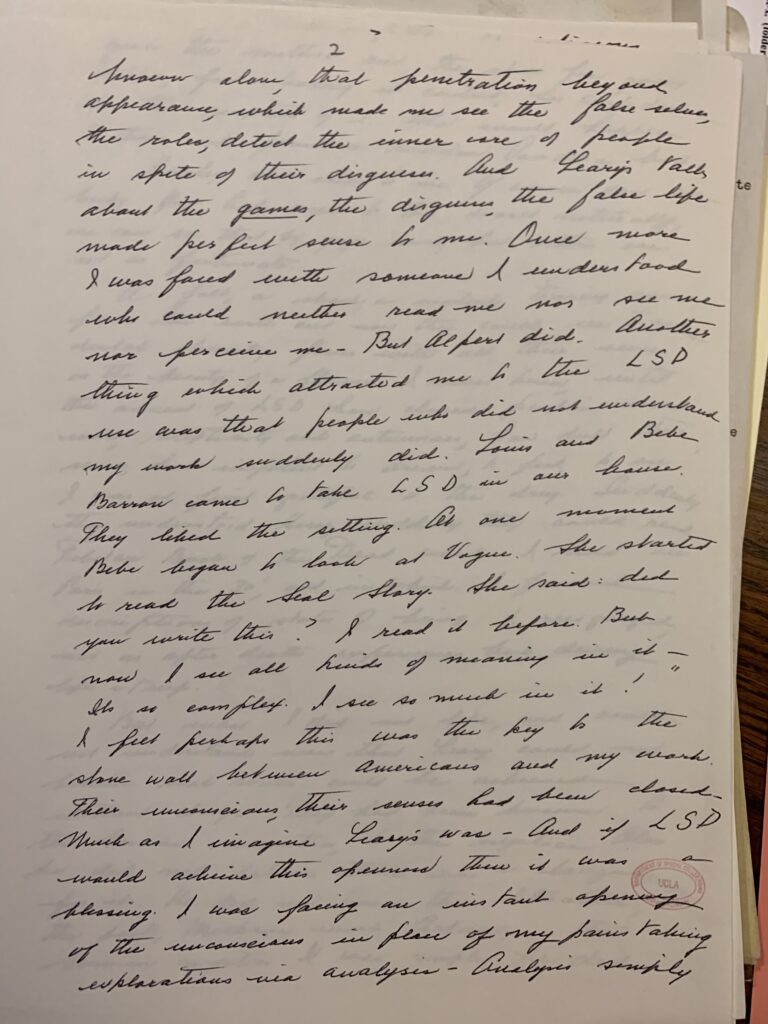

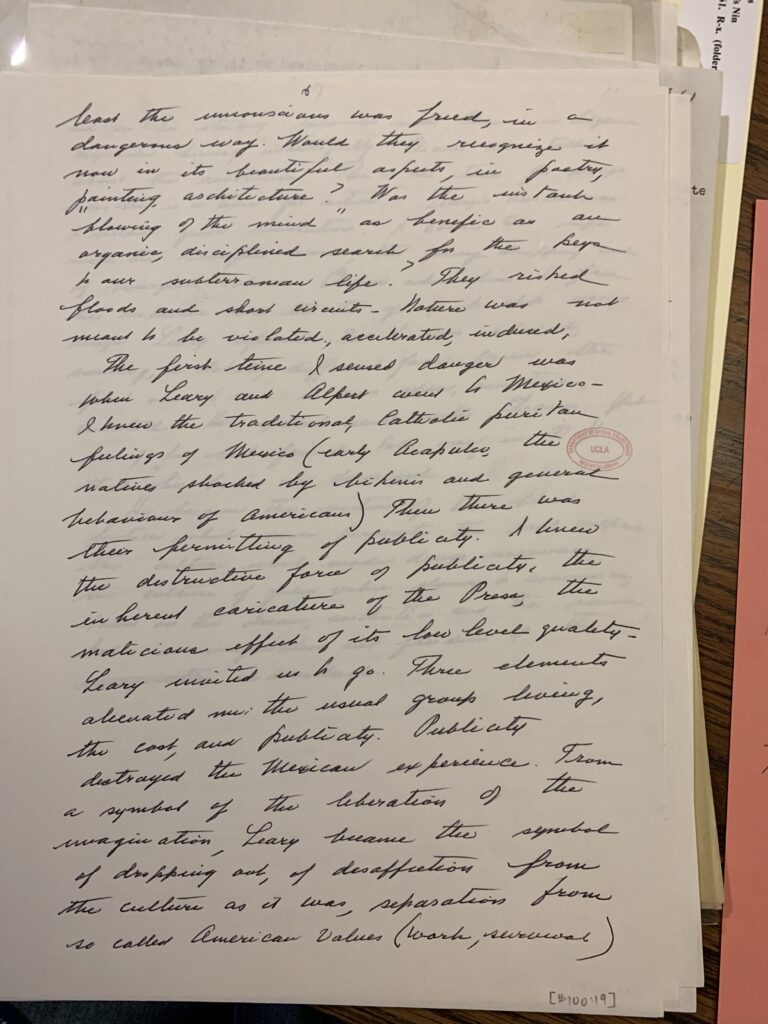

Anaïs first met Tim Leary and Richard Alpert at a party at Virginia’s house overlooking Hollywood Lake, on December 2, 1962. Everyone who was anyone in the LA LSD scene in the late ’50s and early ’60s partied at Virginia’s. Anaïs joined after a friend suggested she be a test subject for Dr. Oscar Janiger’s LSD research experiments several years earlier. Janiger was a regular guest. So were Aldous and Laura Huxley, Christopher Isherwood, and Alan Watts. Disciples would sit meditatively at Watts’ feet in silence, usually hungover. On this evening, Leary and Alpert had arrived fresh from their first summer at the Zihuatanejo Project in Mexico, inviting Anaïs for the second season. She was flattered. “I want them to see your films,” she wrote to her husband Hugo a few days later. “Invitations are rare and special.”

She was not the only one taken with the visitors. Virginia promptly shacked up with Tim for the next several months until he returned to his commune in Mexico. There were problems with the arrangement. André was one, although taking additional lovers had never stopped any of them before. Even Anaïs, troubled as she was by André and Virginia’s relationship, wasn’t troubled because it was an illicit affair. Hell, she was married to two men at once—filmmaker Ian Hugo for when she was in New York, and the actor Rupert Pole for her time in LA.

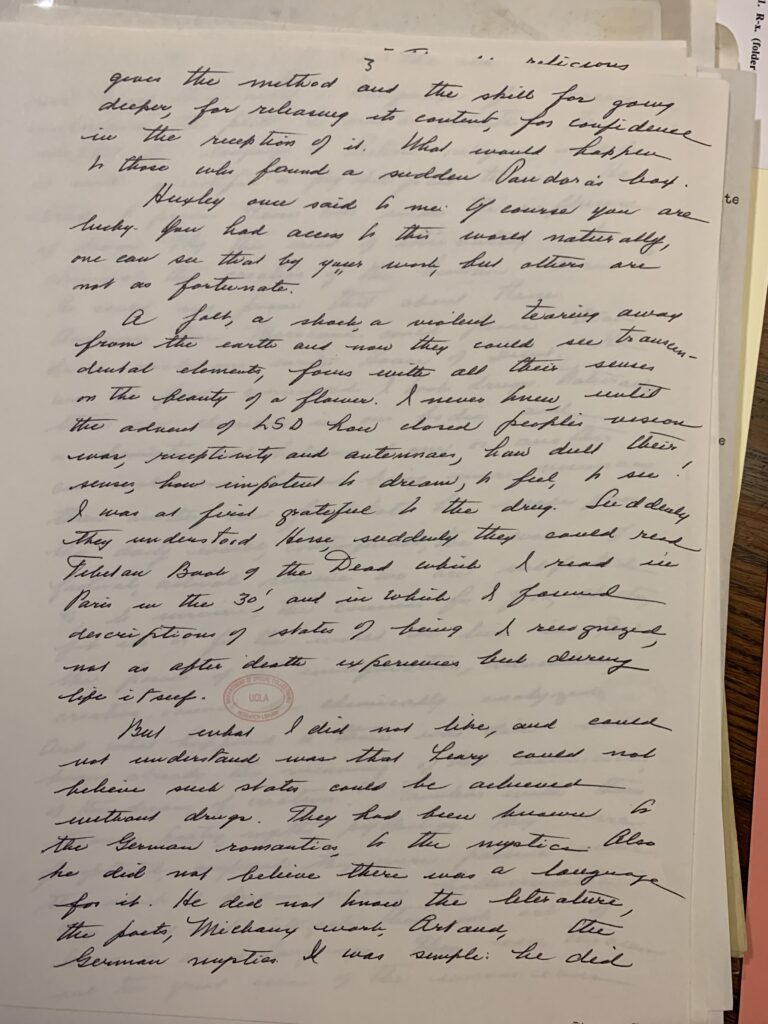

What bothered Anaïs was the fact that André was a clumsy lout and Leary was a cold fish. She was bothered by the contradiction that the willowy yogini who taught her and her husband to breathe deep breaths thrived on abuse and drama. But most of all, if I have read her concerns correctly, she was bothered that Leary seemed so… deaf. Frigidity, for Nin, was a direct consequence of being closed to the world, a pathology American culture cultivated by forbidding imagination, sensuality, and pleasure in the aesthetic realness of the world. Tim sleeping through Virginia’s beating wasn’t simply physical deafness. For Nin, it was a clear sign of emotional deafness.

There was also the problem of Tim’s job. He was supposed to be teaching classes at Harvard that spring. But Timothy Leary was not in Cambridge during the spring of 1963. He was in Virginia Denison’s bed 3,000 miles away, and Anaïs’ diaries make it clear that he was there for months. Leary may have publicly announced he’d been fired for experimenting with LSD, but Harvard, in a rare moment, was telling the truth when they said they fired him for not teaching his classes.

Given the state of the world, I could forgive the reader for wondering whether a historian of science could spend their time in better ways than digging up tawdry gossip. In the grand scheme of things, it likely doesn’t matter that Virginia Denison’s affair helps settle the longstanding question of why Timothy Leary was fired from Harvard in 1963. What’s a bit of truth here and there when we have bigger things to worry about?

“Gossip is overlooked because it’s seen as too womanly. But it’s precisely this invisibility that makes it an excellent device for considering the roles that hero-worship, truth, and ‘importance’ play in American politics.”

If I wish to defend the value of gossip, it’s because I suspect our usual way of conducting business is broken because we can’t be fussed with small matters. We turn to experts and books or to leaders and big ideas when we want guidance. But small money, small ideas, small people? We revile the powerless. And we ignore gossip. It’s seen as too petty, too unimportant, too unvirtuous, too mundane. To put it another way, gossip is overlooked because it’s seen as too womanly. But it’s precisely this invisibility that makes it an excellent device for considering the roles that hero-worship, truth, and “importance” play in American politics. And it’s an excellent source for fact-finding. People are more likely to spill secrets to strangers with little influence over their lives. Those with nothing to lose find it easier to speak truth to power. And something jotted in a diary that will never see the light of day is a lot more likely to be honest.

Join us at Sacred Plants in the Americas II

Work written for public consumption is a different matter. The first time I learned to be careful as a historian was reading Leary’s description of his 1970 jailbreak. The sensuous, concrete details Nin accused him of not paying attention to were exhilarating. Historians don’t get that kind of detail often. But then it hit me. The detail I’d fallen most in love with: the nerdy professor stooping to retrieve his glasses after he jumped the fence, then pushing them back up his nose before running into the night? I’ve never seen a picture of Timothy Leary wearing glasses. He made it up.

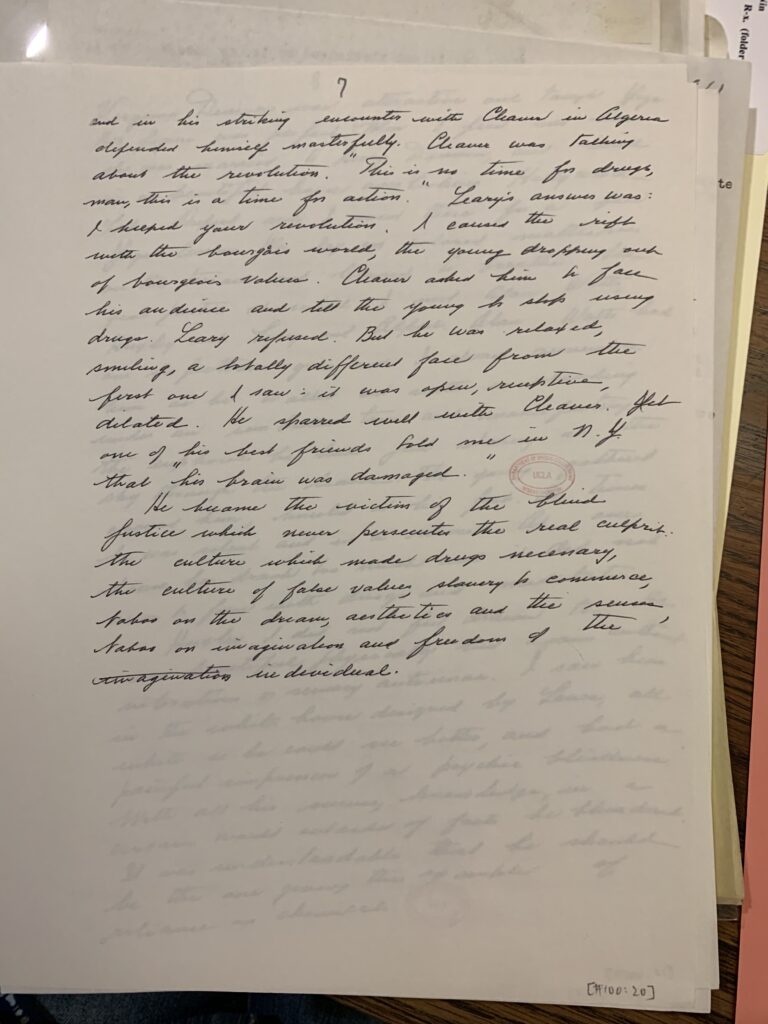

Propaganda is more mundane than nefarious. It’s the simple willingness to sacrifice truth in the name of a bigger goal. “All revolutionaries lie,” Kathleen Cleaver once said. She should know. She was the Black Panther Party’s first Communications Secretary. Her husband, Eldridge, their Minister of Information.

Support the Eagle and the Condor’s Ayahuasca Religious Freedom Initiative

Revolutionaries lie. And politicians. Public figures. Gurus. Anyone who believes their goals outweigh the need for truth. Yet we let this immediately self-evident and banal fact surprise us again and again. Should we really be surprised that Timothy Leary, a man who hired a personal archivist to follow him around while still living, was concerned with a carefully curated public persona? Should we have been surprised when we learned tobacco companies buried scientific research on the link between cancer and smoking for decades? Should we trust a person who says giving everyone psychedelics will solve political strife when that person can’t even maintain peace in their own bedroom? What about someone who does lead a peaceful life, when we see how some other people who take psychedelics behave? If that person is a scientist? A writer? Could we take a shortcut, like Anaïs, and assume that if a person’s methods and approach to the world are like ours’ they can be trusted?

“If I make much of the little things—of gossip and women’s stories and emotions and quibbly things like personal motivation and exceptions to the rules—it’s because smoothing the bits that don’t fit in order to make a tidy story is false.”

If I make much of the little things—of gossip and women’s stories and emotions and quibbly things like personal motivation and exceptions to the rules—it’s because smoothing the bits that don’t fit in order to make a tidy story is false. It’s false when we do it with history. It’s false when we do it with politics. And it’s false when we do it with science. And when we do it enough, should we really expect others to continue to have faith in us? How many scientists have to overstate their claims or hide the more ethically dubious parts of their research for the public to lose faith in the endeavor entirely? When does a guru cease being a guru?

I said that diaries are a special treat for the historian because they weren’t meant to see the light of day, making them especially reliable. That’s usually true. But, again, shortcuts are dangerous. Anaïs was a special case. Fiercely independent, vain, proud, and stifled by the Puritanism she felt in America, she hated having to be dependent on her husbands for her livelihood. Her escape? To sell her diaries. They were never meant to be private. It doesn’t mean we should throw them out as sources, but it does mean we have to take care with them.

“Fiercely independent, vain, proud, and stifled by the Puritanism she felt in America, she hated having to be dependent on her husbands for her livelihood. Her escape? To sell her diaries.”

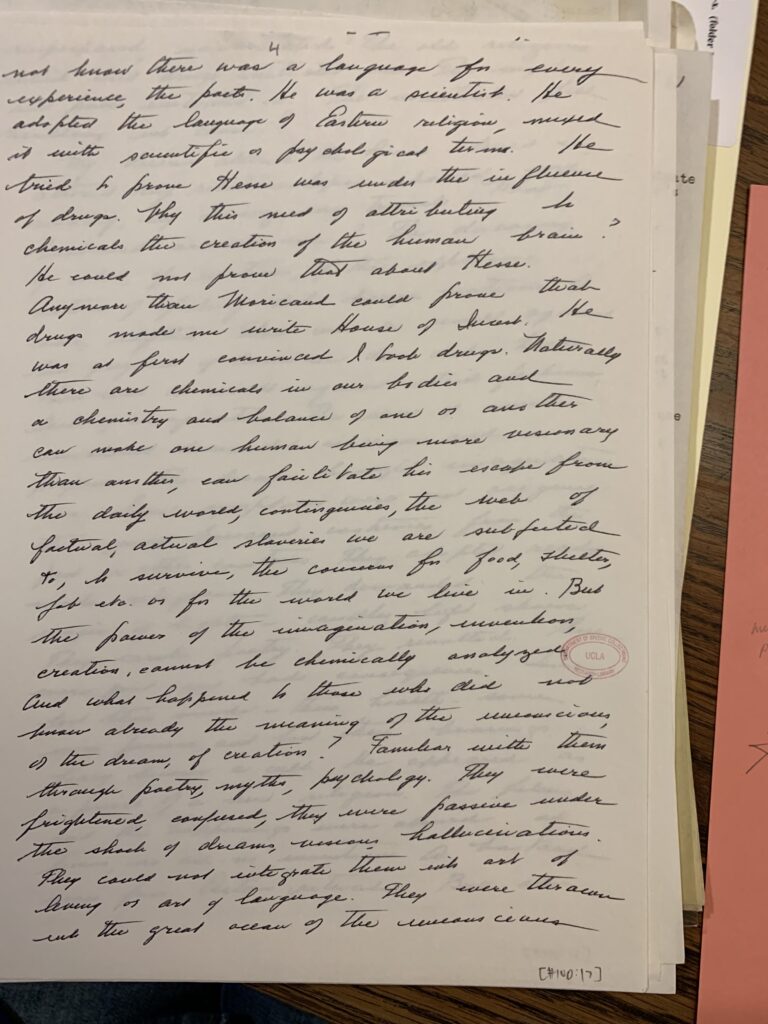

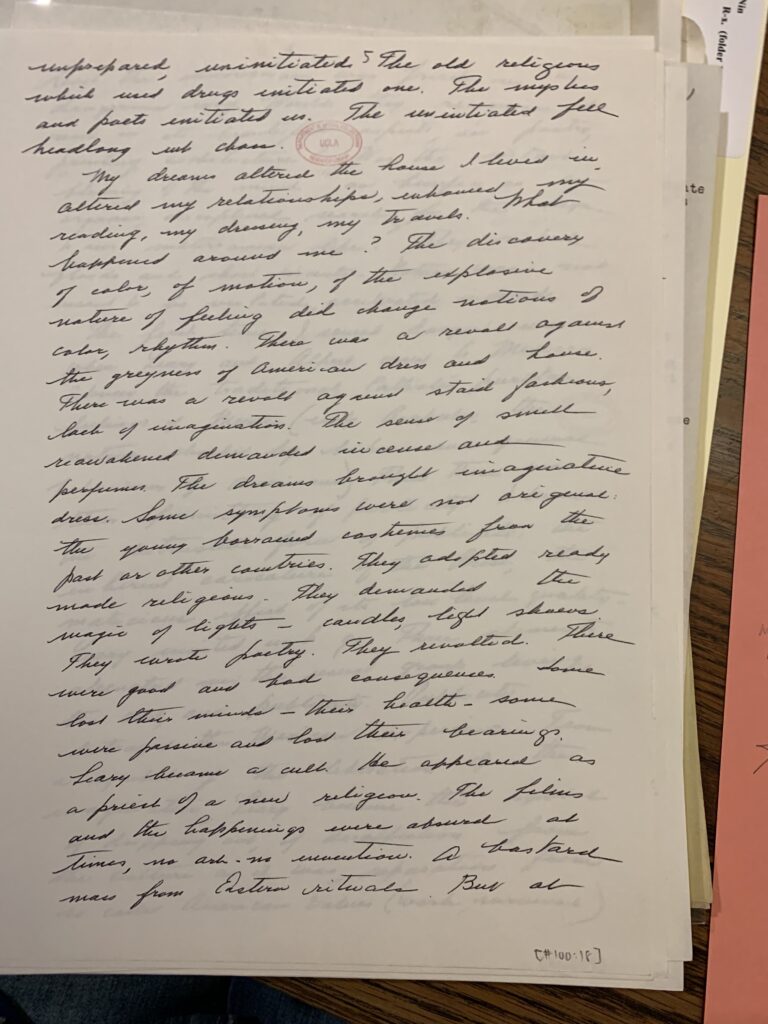

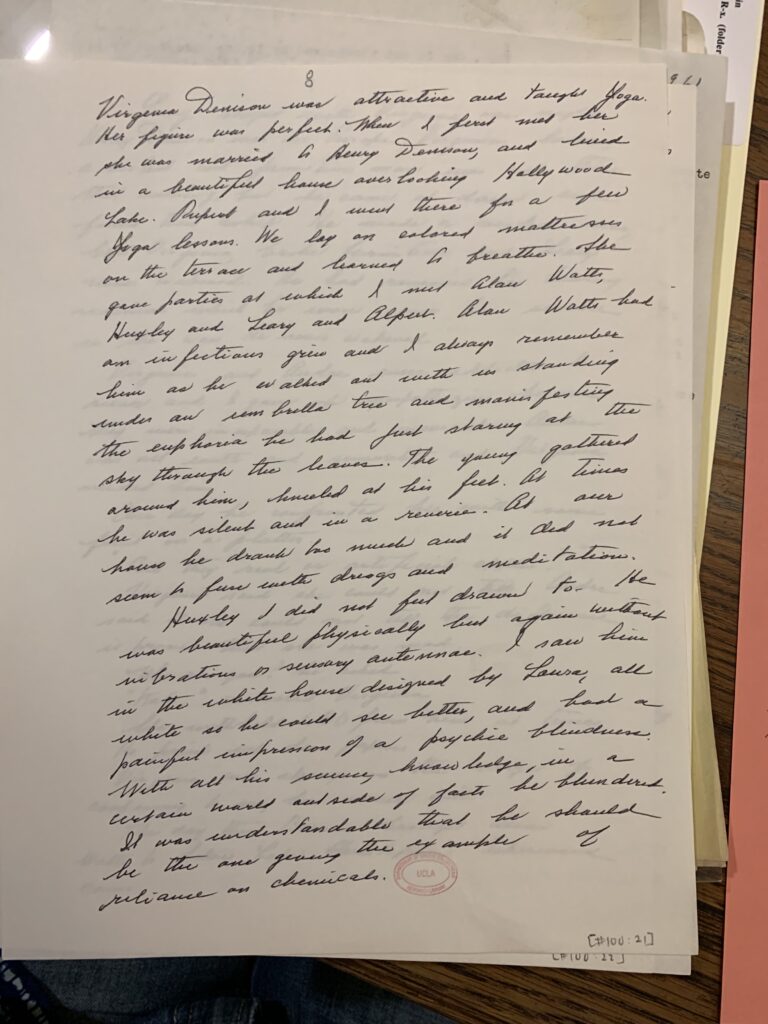

Anaïs didn’t rewrite her entries on Timothy and Virginia to grapple with her friend’s shitty love life. She prided herself on seeing people. She wanted her diaries to reflect that she saw it coming. And so “June 1961” is scribbled atop at least one of the drafts where she works over the story of meeting Leary and Alpert, despite the fact she didn’t meet them until December 1962. Other versions share substantial portions of the same text, making it clear they were drafts of the same story. But one character stands out, helping date the drafts. She describes an exchange Leary had, one that softened her position towards the man she’d elsewhere described as a cult leader. In it, he was open, relaxed, responsive. Newfound traits, she was at pains to note, so unlike the Leary she’d remembered from those early meetings.

And Leary’s interlocutor?

Eldridge Cleaver. Whom he didn’t debate until 1971.

The devil’s in the details. Anyone who tells you otherwise is selling something.

Discover Indigenous Reciprocity Iniciative of the Americas

Author’s Note: The events in this essay have been reconstructed from the Anaïs Nin Papers (Collection 2066), Department of Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, UCLA.

Art by Marialba Quesada.

Take a minute to browse our stock:

Did you enjoy reading this article?

Please support Chacruna's work by donating to us. We are an independent organization and we offer free education and advocacy for psychedelic plant medicines. We are a team of dedicated volunteers!

Can you help Chacruna advance cultural understanding around these substances?