- Introduction to Women and Psychedelics - July 26, 2024

- Mescaline Scribe - February 10, 2021

Simone de Beauvoir’s description of Jean-Paul Sartre’s encounter with mescaline in 1935 is a striking account of a psychedelic experience gone wrong. The episode appears in the second volume of her memoirs, The Prime of Life (1960), and describes a time in their lives long before their rise as two of France’s most famous philosophers. By mid-century, they achieved global fame: even independent of her landmark feminist work The Second Sex (1949), Beauvoir was an accomplished novelist (her 1954 novel The Mandarins won France’s prestigious Prix Goncourt prize), and a founding editor of the influential periodical Les Temps Modernes. Together with Sartre, Beauvoir became a leading figure not only of French existentialism, but also prominently engaged in post-war political activism.

Sartre’s bad trip was vividly captured by Beauvoir’s economical prose; “faces acquired monstrous characteristics… just past the corner of his eye swarmed crabs and polyps and grimacing Things.” The experience resulted in a period of depression for Sartre, but Beauvoir was reluctant to blame the mescaline itself. Indeed, there were many reasons to be depressed at this time, not least (in their eyes) the impending prospects of “turning thirty”—Beauvoir had just turned 27, Sartre would soon cross the threshold. Socially, France and Europe more generally continued to reel in the years after WWI, which saw the rise of authoritarian and fascist political movements. Perhaps as importantly, Beauvoir’s account of Sartre’s bad trip highlights the extreme disconnect from emotional, spiritual, and ceremonial considerations that often occurred in this early stage of psychedelic use in the west.

Beauvoir and Sartre: Young Writers in Love

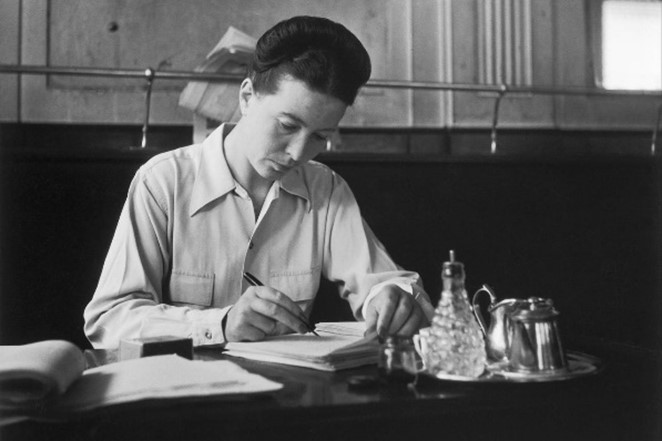

At the time of Sartre’s mescaline experience, it had been five years since they made a pact to be one another’s “necessary other”—neither married, nor monogamous, they nevertheless remained devoted to each other until Sartre’s death in 1980. They had met in 1928 and became close the following year after ranking first (Sartre) and second (Beauvoir) in philosophy in France’s prestigious national exams. They were inspired by literature, art, music, film, history, and philosophy; they wanted to be writers—of essays, plays, short stories, novels, it didn’t matter, as long as they wrote.

“Quite amazingly and without exaggeration Beauvoir read and edited everything Sartre ever published, all the while maintaining her own formidable writing output.”

Quite amazingly and without exaggeration Beauvoir read and edited everything Sartre ever published, all the while maintaining her own formidable writing output. As a teenager, Beauvoir had earned the nickname Castor (Beaver), so notorious was her industry among her classmates. Her unremitting studiousness resulted in works we are still assimilating, not least her masterpieces The Second Sex (1949) and The Coming of Age (1970). But these monumental achievements were at this point far in the future.

Alcohol and Amphetamines

Beauvoir relished the freedom afforded her as an instructor at the girls’ school Jeanne-d’Arc in Rouen, north-west of Paris. Sartre took a teaching position nearby in the coastal city of Le Havre, but felt oppressed by his situation. He feared his best years were behind him, that, as she writes, there would be “no more fresh and blinding revelations”: “We were both still the right side of thirty, and yet nothing new would ever happen to us.”

“Beauvoir had a long and complex relationship with intoxicating substances.”

Beauvoir had a long and complex relationship with intoxicating substances. A cheerful drinker, at the time she was drinking quite a lot, and Sartre complained that when she drank too much, she got too sentimental and poetic, and conflated these states with an intuition for truth. She disagreed and appreciated wine and spirit’s ability to reduce her defenses. Anyway, it was somewhat hypocritical and ironic of him to be so critical of her drinking, as he had his own excesses with alcohol and substances.

Sartre regularly consumed the amphetamine orthedrine and later corydrane (a mixture of aspirin and amphetamine), which were available over the counter in France until banned in the 1960s and early 70s. Discussing his speed use later he said, “The doctors said it’s dangerous now. Too bad, because I loved it… It made my hand move so fast, I couldn’t write faster.” Beauvoir also found occasion to use these substances, but never to the extent of Sartre, who was said to be addicted. She stopped using them altogether by the 1950s.

Phenomenology and Fascism

Like many young intellectuals at the time, they were excited about phenomenology. Phenomenology placed the emphasis on each individual’s direct subjective experience; the aim was to focus on one’s experience without prejudice—free of conceptual categories, abstractions, and ideologies. Emphasizing direct, embodied experience, phenomenology would provide the basis of Beauvoir and Sartre’s emerging existentialism. “The novelty and richness of phenomenology filled me with enthusiasm,” Beauvoir wrote, “I felt I had never come so close to the real truth.”

Beauvoir visited Sartre in Berlin where he was studying. The Nazi party had recently come to power, and the two were in disbelief that such a hyper-nationalistic, militarized, and violent ideology had ascended to power. They saw parades of brownshirts in Hamburg; Beauvoir was berated in Dresden for wearing lipstick. She remarked that the country “doesn’t feel like a dictatorship” and that, at least in the bars and cafes, socializing was “incredibly debauched.”

Join us at Sacred Plants in the Americas II

Crustaceans, Pareidolia, and Depression

Back in France, Sartre tried mescaline, after a friend suggested it “induced hallucinations” but warned that it “would be a mildly disagreeable experience, although not the least dangerous.” Beauvoir records that Sartre thought it might be useful to try mescaline as it would produce an abnormal state of consciousness, in keeping with his present interests in “dreams, dream-induced imagery, and anomalies of perception.”

Michael Jay’s recent study of mescaline describes how at the time of Sartre’s experience, mescaline was widely sought by artists and intellectuals for use “neither as a spiritual epiphany nor a model psychosis, but as a zone of aesthetic, creative and existential possibility.” The severe “de-spiritualizing” of mescaline use at this time is also noteworthy as Jay describes how the pharmacist Alexandre Rouhier’s book Peyote: The Plant That Fills the Eyes with Marvels (1926) had popularized knowledge in France about Indigenous peyote rites of several traditions, and criticized the growing and commonplace assumption that mescaline independent of the cactus and its rituals was an equivalent experience. Rouhier thought of peyote as a “divinatory palaeo-pharmacy,” something to be respected and revered—not merely as a chemical to induce changes in brain function and perception.

Alexandre Rouhier “criticized the growing and commonplace assumption that mescaline independent of the cactus and its rituals was an equivalent experience” to Indigenous peyote rites.

When Sartre visited Lagache at Saint-Anne Hopital in Paris that chilly winter morning to be injected with mescaline, it was in a highly clinical setting, bereft of the ritualistic, ceremonial, spiritual, or even medical elements. The object, Lagache had said, was to hallucinate, which is what Sartre did. As arranged, Beauvoir would wait at a friend’s apartment and call the hospital after a few hours. When she called, Sartre said in a “thick, blurred voice, that my phone call had rescued him from a battle with several devil-fish.” She went to Saint-Anne’s to retrieve him. In the train car on the way home Sartre was silent, speaking only to tell Beauvoir about the “dung beetles” on her shoes and about a “leering” orangutan he believed was hanging by its feet outside the train gazing in at them.

Over the next few days, Beauvoir and Sartre were uncharacteristically incommunicative; she records being “irritated” by his “surliness.” Later she learned that Sartre was in a state of severe depression. He had been deeply affected by his mescaline experience and was anxious and fearful. He saw faces everywhere: “houses had leering faces, all eyes and jaws… every clockface… the features of an owl.” Beauvoir considered it likely that Lagache’s warning of possibly bleak experiences primed Sartre in that direction. It likely did not help that Sartre’s vision had been severely compromised since losing sight in his right eye following a childhood illness.

Most famously, he was regularly accompanied by some sort of crustacean; Beauvoir refers to a “lobster trotting behind him,” though in a later interview he describes a plurality of “crabs and lobsters.” The situation got so dire that Sartre genuinely thought he was in danger of psychosis. When Beauvoir tried to calm him, he was dismissive: “’Your only madness,’ I told him, ‘is believing that you’re mad.’ ‘You’ll see,’ he replied gloomily.”

Discover Indigenous Reciprocity Initiative of the Americas

Leaving a Legacy

Reading Beauvoir’s account of Sartre’s bad trip is important for several reasons. In the first place, Sartre had very little to say about it; what little he did, in the eventual text The Psychology of the Imagination (1938), does not mention the crustaceans nipping at his heels. However, in a 1972 interview with John Gerassi he did revisit the experience:

“Never tried coco, opium, or heroin. Or LSD for that matter, although I gather that it has some of the same effects as peyote, you know, mescaline, which I used to take. I think that’s how I first started hallucinating my crabs and lobsters. But it wasn’t nasty. They would walk along with me, on my side, but not crowding me, very politely, I mean, not threatening. Until one day I got fed up. I just said, OK beat it, and they did. I liked mescaline a lot. As you know I am not a nature lover.”

Beauvoir’s account is perhaps most valuable, as it records a moment in time before either writer had taken on their larger-than-life reputations. Beauvoir describes their engaged struggle for those trademark Beauvoirian/Sartrean themes of “freedom,” “responsibility,” and “choice” at a time of rising radicalization and polarization in French and broader society. It is not difficult, if a little speculative, to imagine that the marching lobsters and crabs were in some way associated with the boot-stomping fascists they had seen in Germany just months before.

Further, coupled with his fatalistic sense of his own failures, that turning thirty amounted to a personal crisis, it is not surprising that Sartre’s mescaline experience was so disturbing. It shows the extent to which a person’s “head space” can impact a psychedelic experience, to say nothing of set and setting.

Finally, Beauvoir’s engrossing account of this episode in their busy lives is a literary treasure in its own right. Perhaps the only thing that could improve it from this perspective would have been if she had taken mescaline—or better yet, peyote—herself. Her words are vivid enough describing the experiences of others, we can only imagine what she might have written had she been the one to lead the lobster parade.

Art by Mariom Luna.

Take a minute to browse our stock:

Did you enjoy reading this article?

Please support Chacruna's work by donating to us. We are an independent organization and we offer free education and advocacy for psychedelic plant medicines. We are a team of dedicated volunteers!

Can you help Chacruna advance cultural understanding around these substances?