- Participation in an Indigenous Amazonian-led Ayahuasca Retreat Associated with Increases in Nature Relatedness – A Pilot Study - March 21, 2024

- A Phenomenology of Subjectively Relevant Experiences Induced by Ayahuasca in Upper Amazon Vegetalismo Tourism - November 9, 2023

- The Pharmacological Interaction of Compounds in Ayahuasca: A Systematic Review - October 26, 2023

Wolff, T. J., Ruffell, S., Netzband, N., & Passie, T. (2019). A phenomenology of subjectively relevant experiences induced by ayahuasca in Upper Amazon vegetalismo tourism. Journal of Psychedelic Studies, 3(3), 295-307. DOI: 10.1556/2054.2019.007

Study Rationale

There has been a substantial increase in the amount of quantitative research investigating the potential of ayahuasca therapeutically over the last decade. Although informative, numerical data fails to emphasise the impact that context has on the participant under study (Barbour, 2000), which is arguably essential when considering the Indigenous ceremonial use of Amazonian ayahuasca. Furthermore, using only quantitative data limits our ability to determine the psychological processes underlying change in psychometrics. To address these issues, a heuristic study was conducted to further explore the phenomenology of the ayahuasca experience in a traditional setting.

Methodology

Participants underwent six ayahuasca ceremonies in a group setting at the Ayahuasca Foundation, Peru. Interviews took place in the morning, immediately after the second ayahuasca ceremony had finished. A narrative interview strategy was chosen (Küsters, 2009) to minimize any potential bias or leading questions relating to the study (Patton, 2002). Participants were asked to report what they had experienced during the ceremony, for example, “please tell me about your experiences during the ceremony as openly as possible.” An open question about emotional experience was subsequently added to the narrative interview since, in contrast to traditional local ayahuasca use in the upper Amazon region (De Rios, 1972), the focus for western clients is often on psychotherapeutic processes (Beyer, 2009). Interviews were sound recorded. After transcription, interviews were analysed through qualitative content analysis (QCA) using a mixed data-driven strategy. A progressive-paraphrasing strategy was combined with a subsuming strategy (Schreier, 2012). This allowed for the extraction of themes and commonalities among subjective experiences, without prompting and overly influencing results. For the first interview, the material was cut into single statements; all statements (coding units) were paraphrased to build up provisional main categories. Similar paraphrases with shared meaning were paraphrased again. In this way, abstract categories were formed. For the additional material, statements were used to build up subcategories, and further statements were either subsumed under these already existing subcategories or new subcategories were formed. The coding-frame was built up successively until a point of saturation was reached. After the ninth interview, no further categories had to be introduced to classify new material.

Discover the Indigenous Reciprocity Initiative of the Americas

Summary of Results

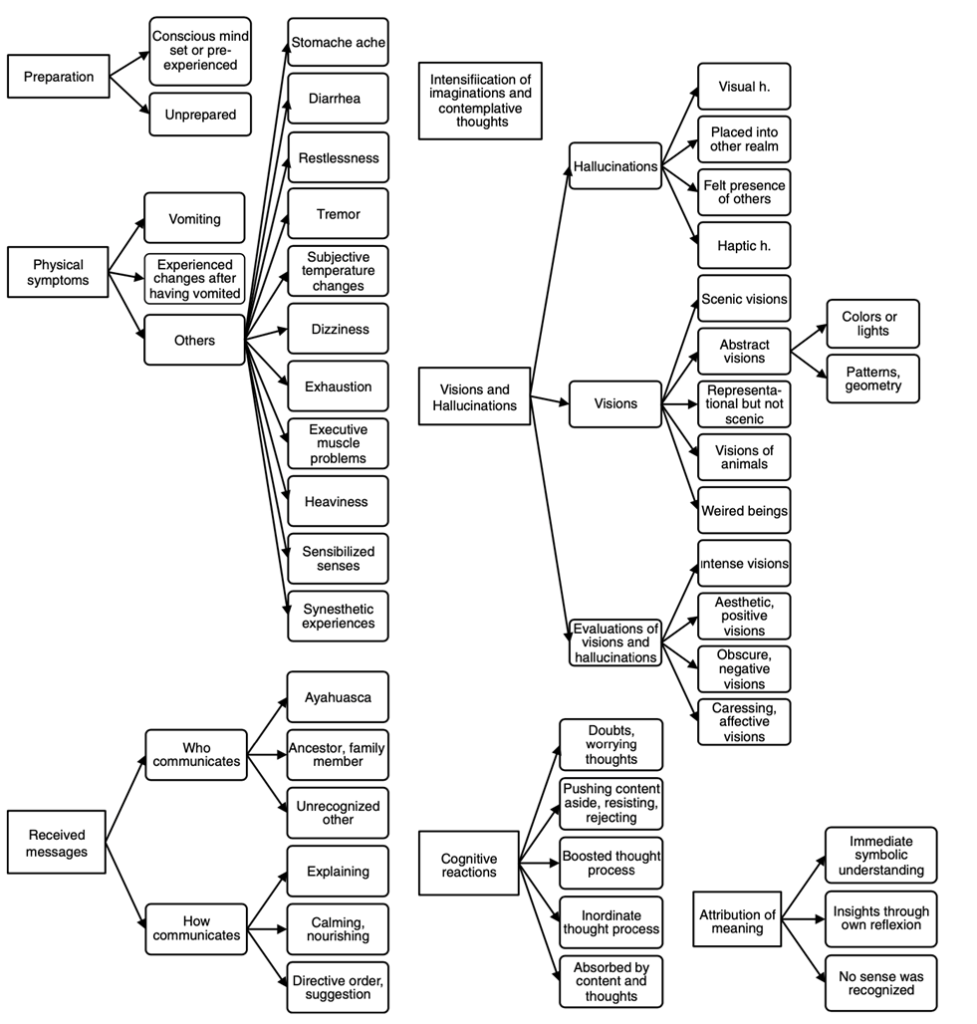

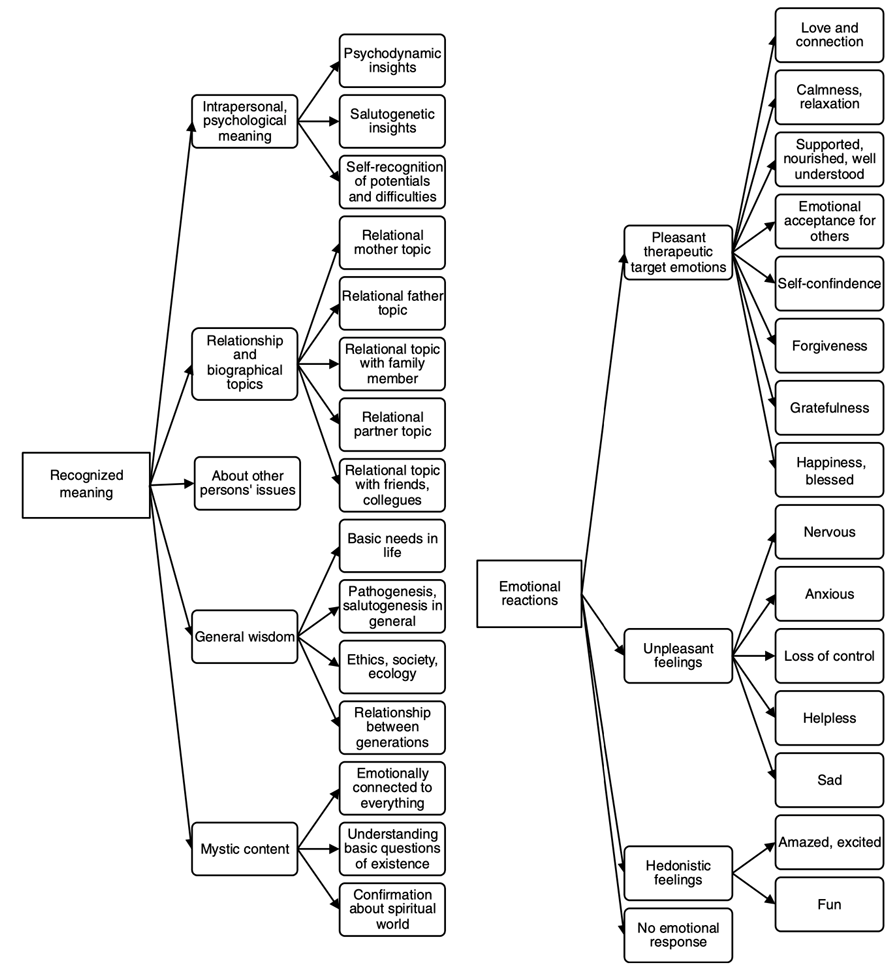

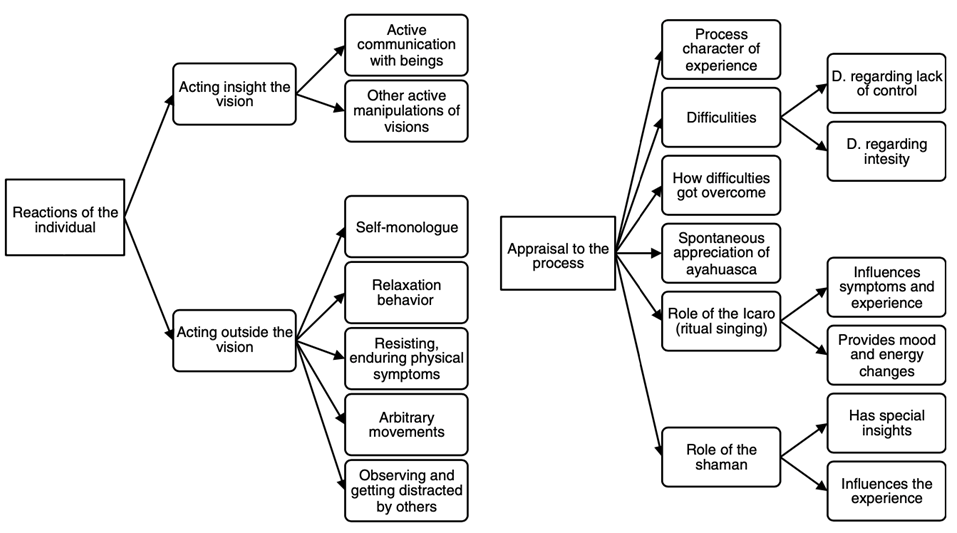

One overarching topic was identified: experiences during the ceremony (Figure 1), along with two side categories: appraisal of the process (Figure 2) and preparedness (Figure 3). Various subthemes were identified from the main category, including physical symptoms, received messages, visions and hallucinations, cognitive reactions, attribution of meaning, recognised meaning, emotional reactions, and reactions of the individual.

Figure 1

Preparation, physical symptoms, phantasies, visions, received messages, cognitive reactions, and attribution of meaning reported after a shamanic ayahuasca ceremony in the Amazon region in narrative interviews of nine foreign participants using qualitative content analyses.

Figure 2

Recognized meaning of psychedelic content and emotional reactions reported after a shamanic ayahuasca ceremony in the Amazon region in narrative interviews of nine foreign participants using qualitative content analyses.

Figure 3

Appraisal of the process, role of ritual singing and of the shaman, individual reactions reported after a shamanic ayahuasca ceremony in the Amazon region in narrative interviews of nine foreign participants using qualitative content analyses.

Integration with extant literature

This study was designed to identify possible implications for psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy for Western clients using psychedelics as medicines, as well as commonalities in subjective experiences with ritualistic ayahuasca use in retreat settings. Although the use of coding manuals in QCA makes it less appropriate for deriving meaning, it does allow for rich phenomenological understanding of the participant’s journey, with the potential to illuminate any psychotherapeutic processes that may have been occurring (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005).

Experiences During the Ceremony

Physical Symptoms

Although similarities exist between the subjective ayahuasca experience and other psychedelics, ayahuasca is unique in several domains. It has a prominent somatic component, with somatic symptoms comprising 12.43% of the qualitative reports. It is well established in the literature that both kinaesthetic and somatic awareness are enhanced throughout the ayahuasca experience (Espinoza, 2014; Kaufman, 2015; Shanon, 2002). Shanon (2014) describes the somatic aspect of the ayahuasca experience as the primary psychotherapeutic modality.

Those who drink ayahuasca often describe the sensation that something foreign has taken hold, frequently explained as an energetic force entering the body and nervous system at the start of ayahuasca ceremonies (Shanon, 2002). Furthermore, these physical effects can be interlinked with psychological insights and spiritual experiences (Shanon, 2002). Intimate awareness of body parts with a heightened awareness of proprioception is often connected to self-healing (Shanon, 2002, 2014). Participants engaging in ayahuasca ceremonies describe a spectrum of sensation, encompassing pain and emotional release from embodied trauma to an ecstatic sense of love and awe (Shanon, 2002).

Ayahuasca characteristically is associated with nausea and vomiting, leading some to refer to it as la purga (MacRae, 2004). The nauseating effects of the tea are largely due to the effect of the harmala alkaloids on stomach enzymes, and of N,N-Dimethyltryptamine (DMT) present in the intestines acting on serotonin receptors (Domínguez-Clavé et al., 2016; Gershon, 2004). Although vomiting would usually be considered a side effect of a drug, this is not so in the traditional use of ayahuasca (Tafur, 2017). Rather it is thought of as having significant therapeutic benefit, with users reporting emotional release, psychological benefits, and even long-lasting transformative effects. Some traditions even refer to the purge as getting well (Gearin, 2016; Lafrance et al., 2017; Rush et al., 2021; Shanon, 2002, 2014).

Van der Kolk (2014) writes that to identify specific emotions connected to bodily sensations, one must be connected to deep psychological states. This in turn allows for better recognition, understanding and control of emotion. Brain imaging studies have shown that areas like the anterior insula and the paralimbic region are activated upon ayahuasca consumption (Riba et al., 2006). These areas are associated with emotional processing, interoception, and somatic awareness (Riba et al., 2006; Wang et al., 2019). Furthermore, disruptions in the anterior insular and consequently interoceptive processing are associated with a variety of disorders, such as depression (Wiebking et al., 2015), addiction (Paulus et al., 2013), childhood trauma and PTSD (Reinhardt et al., 2020). This theory forms the basis of somatic-orientated psychotherapies, which have recently attracted substantial interest (Davis, 2021). Interestingly, longitudinal research has also suggested decreased rates of bodily dissociation in ayahuasca drinkers (Kaufman, 2015).

Find more information on the upcoming Psychedelic Culture Conference.

Emotional Reactions

All participants interviewed in this study described emotional release and corrective emotional experiences as a result of drinking ayahuasca. These were divided into desirable, unpleasant, and hedonistic emotional states. Unpleasant emotional states were often followed by pleasant ones, suggesting potential resolution. This is in line with the psychotherapeutic processes associated with psychodynamic psychotherapy, for example, when challenging immature psychological defence mechanisms which consequently results in positive therapeutic outcomes (Drapeau et al., 2003; Owen et al., 2015; Perry & Bond, 2012). Furthermore, the brew has been suggested to disable defence mechanisms, with participants left to face intense emotions and experiences directly (Nielson & Megler, 2014; Perkins & Sarris, 2021).

The quality of the acute psychedelic experience has been demonstrated with psilocybin to predict therapeutic efficacy (Roseman et al., 2018). Roseman and colleagues demonstrated that low Dread of Ego Dissolution (DED), a dimension of the Altered States of Consciousness (ACS) questionnaire assessing challenging experiences similar to anxiety, and high Oceanic Boundlessness (OBN) were found to predict positive outcomes on the Self-Reported Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptoms (QIDS-SR) at 5-week follow-up. Although this would appear to suggest challenging experiences during psychedelic sessions are negatively associated with therapeutic outcome, it appears a less simplistic viewpoint is required. In a subsequent study by Roseman et al. (2019), emotional breakthrough, a phenomena bearing similarity to the psychoanalytic principle of catharsis, was found to mediate long-term therapeutic outcome. This finding is in keeping with various therapist’s accounts and modern phenomenological analyses emphasising the importance of working through challenging emotional states (Belser et al., 2017; Bonny & Pahnke, 1972; Gasser et al., 2014; Watts et al., 2017). Although challenging experiences have been shown to correlate with negative therapeutic outcomes (Roseman et al., 2018), it appears that if such experiences are resolved, as in the case with emotional breakthrough, they can successfully predict well-being in the long-term (Roseman et al., 2019).

Research has shown that drinking ayahuasca is associated with heightened self-love (Lafrance et al., 2021), which in turn improves interpersonal relationships and results in higher levels of empathy. Furthermore, those who consume the brew have been found to be more present in themselves, more self-aware, and have a greater degree of self-acceptance (Kjellgren et al., 2009; Soler et al., 2016). These desirable emotional states have been found to be associated with improvements in psychological well-being (Perkins, Schubert, et al., 2021), as well as being a focus in various third wave Cognitive Behaviour Therapies (CBT), such as compassion-focused therapy, which have demonstrated positive effects in the literature (Gilbert, 2009).

Research suggests ayahuasca can improve the ability to observe thoughts and emotions from a state of detachment (Fresco et al., 2007). Known as decentring, this cognitive ability is hypothesised to be a transdiagnostic index of psychopathology and is a core component of Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (Safran & Segal, 1996; Soler et al., 2016). Interestingly, an association between self-connection and response to the treatment of addiction has been identified, as has self-acceptance and self-love in therapeutic outcomes more generally (Argento et al., 2019; Renelli et al., 2020; Thomas et al., 2013).

Received Messages

Direct communication with entities were reported in three of the nine qualitative accounts. The appearance of supportive entities is a key feature of traditional ayahuasca use and helps to distinguish it from western psychedelic-assisted therapy (Beyer, 2009; De Rios, 1972; Luna, 1986). It should be noted, however, that such phenomena are also rarely described in Western psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy sessions, as well as non-drug assisted psychotherapy (Belser et al., 2017). In Internal Family Systems (IFS) therapy, Falconer (2021) describes supportive entities largely presenting as guiding spirits from family members. The impact of such encounters, their nature, and the role different expectations have on the phenomenology could be the subject of future research.

Recognized Meaning

Seven of the nine participants interviewed described gaining insightful and personal meaning during their ayahuasca ceremonies. Five subcategories were further derived, including: interpersonal psychological insights; insights into relational issues; insights into the motives and issues of others; general social, ethical, and environmental wisdom; and mystical, spiritual, and religious insights and experiences.

Many subjects spontaneously described relationship issues in their interview sessions. Like other psychedelic-assisted therapies, new perspectives in interpersonal issues are an integral part of ayahuasca-therapy (Belser et al., 2017; Gasser et al., 2014). Furthermore, psychodynamic psychotherapy often addresses preconscious intrapersonal conflicts, conflicts of the biographical past, relational conflicts, and social representations (Grawe, 2004). Ayahuasca appears to induce a state in which participants can reassess these issues and acquire new perspectives, providing potential psychotherapeutic value (Grawe, 2004).

Most who choose to engage with psychedelic therapy do so with the expectation of achieving emotional healing and a better understanding of self (Winkelman, 2014). Psychedelics have been demonstrated to lead to insightful psychodynamic, cathartic, and interpersonal experiences (Gasser et al., 2014). New self-narration is a common aim in psychotherapy, defined as a fresh evaluation of identity and relationship with one’s surroundings, as well as the potential rescripting of life narrative (Jørgensen, 2006). Enhanced connection to nature appears to be encompassed within connection to the universe. Research suggests that connection to the planet, others, and self is a spiritual value common to psychedelic substance use (Carhart-Harris et al., 2018; Watts et al., 2017). Furthermore, these mystical, spiritual, and religious understandings appear to have therapeutic value, both in treating mental illnesses such as addiction, as well as facilitating new perspectives on life (Kjellgren et al., 2009; Liester & Prickett, 2012; Loizaga-Velder & Verres, 2014; Renelli et al., 2018). Individuals drinking ayahuasca can also experience perceived near-death experiences (NDEs). NDEs as a result of psychedelics have been associated with improvements in psychological distress, change towards health-related behaviours, diminished death anxiety in those with terminal illnesses and improvements in wellbeing in the long-term (Loizaga-Velder, 2013; Maia et al., 2021; Timmermann et al., 2018).

Spiritual and religious counselling regarding ayahuasca consumption has been shown to be beneficial with integration, is associated with enhanced mental wellbeing and can lead to larger numbers of personal insights (Perkins et al., 2021). It is well established in psychedelic research that the strength of participants’ perceived mystical experiences predicts therapeutic outcomes (Perkins et al., 2021; Russ et al., 2019). Research has found that these foster the feeling of connection with plant intelligence, the natural world and an understanding pertaining to the connection between all things (Harris & Gurel, 2012; Shanon, 2002).

Attribution of Meaning

Participation in ayahuasca ceremonies often results in novel insights and perspectives which can have therapeutic value (Frecska et al., 2016; Kjellgren et al., 2009). The meaning associated with these experiences often lends itself to the re-evaluation of current and historical events. Such insights have been found to correlate with improvements in depression, anxiety, and psychological wellbeing as well as reduced drug and alcohol consumption (Perkins et al., 2021; Perkins et al., 2021; Sarris et al., 2021). These understandings are further related to physical health, novel creative pursuits, enhanced life purpose, as well as interpersonal and psychodynamic factors (Kavenská & Simonová, 2015; Kjellgren et al., 2009; Shanon, 2002). Research suggests insights can result in meaningful life change in the aforementioned areas (Bouso et al., 2012; Franquesa et al., 2018; Loizaga-Velder, 2013; Maia et al., 2021).

Visions and Hallucinations

Visual phenomena are a common experience in ayahuasca ceremonies, and eight of the nine participants discussed this in their interviews. Visions during ayahuasca ceremonies can result in the reprocessing of autobiographical memory, including traumatic experiences (Echenhofer, 2011; Perkins, Sarris, et al., 2021; Shanon, 2002). Despite being in an altered state of consciousness, participants’ mental clarity is often described as being enhanced, allowing for an accelerated psychotherapeutic process with intense self-evaluation. The identification of dysfunctional coping strategies, as well as maladaptive emotional and behavioural patterns are often identified and addressed (Argento et al., 2019; Franquesa et al., 2018; Frecska et al., 2016; Renelli et al., 2018).

Cognitive Reactions

Ayahuasca drinkers often describe what is referred to in our qualitative analysis as boosted thought processes. This is in concordance with research suggesting that 90% of those who engage in ayahuasca rituals experience a dramatic increase in their perceived level of understanding (Bresnick & Levin, 2006). Although boosted thought processes can result in critical self-analysis regarding interpersonal relationships, self-care, and the potential aetiology of psychological distress (Franquesa et al., 2018; Loizaga-Velder & Verres, 2014; Maia et al., 2021), it can also result in emotional distress and discomfort as participants are forced to confront issues that may be unpleasant or fear inducing (Franquesa et al., 2018; Loizaga-Velder & Verres, 2014; Maia et al., 2021). Despite this, such experiences are generally considered of therapeutic benefit, as is the case when confronting issues in standard talking therapies, such as psychodynamic psychotherapy and CBT (Bresnick & Levin, 2006; Kjellgren et al., 2009; Maia et al., 2021; Shanon, 2002).

Deep cognitive processes seem to be induced by providing access to otherwise unobtainable emotional material whilst activating higher cortical areas (Nielson & Megler, 2014). Several factors have been described in psychedelic-assisted therapy, including transpersonal experiences, corrective new experience, problem actualisation, rescripting of past behaviours, regression and the acceleration of psychological processes, all of which are often associated with emotional activation (Passie et al., 2012). These processes can result in the reprocessing, reframing and reintegration of significant life events and emotional associations (Nielson & Megler, 2014). This theory is supported by Carhart-Harris and Friston (2019) in their REBUS model which describes the relaxation of existing beliefs through disruption of neural hierarchies and consequently results in emotional and psychological insights. The importance of integration following such processes has been stressed to ensure insights result in beneficial change and prevent psychological harm (Perkins et al., 2021).

Appraisal of the Process

The importance of ceremony is currently a topic of debate as researchers work towards the potential medicalisation of ayahuasca and other psychedelics. There are various explanations regarding the impact of the shaman and the singing of icaros, which were mentioned by over half the participants. Participants in ayahuasca rituals could be more prone to the placebo effect (Palhano-Fontes et al., 2019), their altered state of consciousness interacting with positive thoughts and emotions surrounding the shamanic aspect of the ceremony. An alternative explanation is that the shamanic aspect of the ceremony provides healing in a psychospiritual capacity. A study by Weiss et al. (2021) assessing ceremonial ayahuasca use suggests that the mystical states occasioned by ayahuasca act as a covariate that significantly interacts with positive prior perceptions of shamanic tradition. Furthermore, in the same study, the belief that ayahuasca was cleaning the body, through purging and spiritual means, was found to significantly predict long term change in both Neuroticism and Extraversion. Although purging was found to induce positive change quantitatively, this was not generally true for other shamanic features used within the ceremonial setting (Weiss et al., 2021).

Study Relevance

Although some of the ayahuasca experiences described can be difficult to interpret through a Western scientific lens, it appears that there are similarities between many of the user accounts described by Westerners on an experiential level. Most subjective reports focused on experiences during the ceremony, with data suggesting ayahuasca consumption does not necessarily result in psychotherapeutic effects. Available literature suggests therapeutic benefit is significantly enhanced with integration sessions following psychedelic ingestion, although empirical data in this area is lacking (Earleywine et al., 2022; Perkins et al., 2022). In most participants in this study, insights were acquired without necessarily fully integrating these. This is interesting to consider, as the majority of ayahuasca retreat centres do not offer integrative psychotherapy as part of their package of care. The psychotherapeutic potential for participants to learn and process their experiences could potentially be enhanced with additional preparation and integration sessions, although further research in this area is required.

Shop our Collection of Psychedelic T-Shirts.

References

Argento, E., Capler, R., Thomas, G., Lucas, P., & Tupper, K. W. (2019). Exploring ayahuasca‐assisted therapy for addiction: A qualitative analysis of preliminary findings among an Indigenous community in Canada. Drug and alcohol review, 38(7), 781-789.

Barbour, R. S. (2000). The role of qualitative research in broadening theevidence base’for clinical practice. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 6(2), 155-163.

Belser, A. B., Agin-Liebes, G., Swift, T. C., Terrana, S., Devenot, N., Friedman, H. L., Guss, J., Bossis, A., & Ross, S. (2017). Patient experiences of psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy: an interpretative phenomenological analysis. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 57(4), 354-388.

Beyer, S., V. (2009). Singing to the Plants: A Guide to Mestizo Shamanism in the Upper Amazon. University of New Mexico Press.

Bonny, H. L., & Pahnke, W. N. (1972). The use of music in psychedelic (LSD) psychotherapy. Journal of Music Therapy.

Bouso, J. C., González, D., Fondevila, S., Cutchet, M., Fernández, X., Ribeiro Barbosa, P. C., Alcázar-Córcoles, M. Á., Araújo, W. S., Barbanoj, M. J., & Fábregas, J. M. (2012). Personality, psychopathology, life attitudes and neuropsychological performance among ritual users of ayahuasca: a longitudinal study.

Bresnick, T., & Levin, R. (2006). Phenomenal qualities of ayahuasca ingestion and its relation to fringe consciousness and personality. Journal of Consciousness Studies, 13(9), 5-24.

Carhart-Harris, R. L., Erritzoe, D., Haijen, E., Kaelen, M., & Watts, R. (2018). Psychedelics and connectedness. Psychopharmacology, 235(2), 547-550.

Carhart-Harris, R. L., & Friston, K. (2019). REBUS and the anarchic brain: toward a unified model of the brain action of psychedelics. Pharmacological reviews, 71(3), 316-344.

Davis, S. (2021). Tracing somatic therapies. The Lancet Psychiatry, 8(4), 282-284. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2215-0366(21)00086-9

De Rios, M. D. (1972). Visionary vine: psychedelic healing in the Peruvian Amazon. Chandler Publishing Company.

Domínguez-Clavé, E., Soler, J., Elices, M., Pascual, J. C., Álvarez, E., de la Fuente Revenga, M., Friedlander, P., Feilding, A., & Riba, J. (2016). Ayahuasca: pharmacology, neuroscience and therapeutic potential. Brain research bulletin, 126, 89-101.

Drapeau, M., De Roten, Y., Perry, J. C., & Despland, J.-N. (2003). A study of stability and change in defense mechanisms during a brief psychodynamic investigation. The Journal of nervous and mental disease, 191(8), 496-502.

Earleywine, M., Low, F., Lau, C., & De Leo, J. (2022). Integration in Psychedelic-Assisted Treatments: Recurring Themes in Current Providers’ Definitions, Challenges, and Concerns. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 00221678221085800.

Echenhofer, F. (2011). Ayahuasca shamanic visions: Integrating neuroscience, psychotherapy, and spiritual perspectives. A field guide to a new metafield: Bridging the humanities-neurosciences divide, 153-203.

Espinoza, Y. (2014). Sexual healing with Amazonian plant teachers: a heuristic inquiry of women’s spiritual–erotic awakenings. Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 29(1), 109-120.

Falconer, R. (2021). IFS and psychedelics.

Franquesa, A., Sainz-Cort, A., Gandy, S., Soler, J., Alcázar-Córcoles, M. Á., & Bouso, J. C. (2018). Psychological variables implied in the therapeutic effect of ayahuasca: A contextual approach. Psychiatry research, 264, 334-339.

Frecska, E., Bokor, P., Andrassy, G., & Kovacs, A. (2016). The potential use of ayahuasca in psychiatry. Neuropsychopharmacologia Hungarica: a Magyar Pszichofarmakologiai Egyesulet Lapja= Official Journal of the Hungarian Association of Psychopharmacology, 18(2), 79-86.

Fresco, D. M., Moore, M. T., van Dulmen, M. H., Segal, Z. V., Ma, S. H., Teasdale, J. D., & Williams, J. M. G. (2007). Initial psychometric properties of the experiences questionnaire: validation of a self-report measure of decentering. Behavior therapy, 38(3), 234-246.

Gasser, P., Holstein, D., Michel, Y., Doblin, R., Yazar-Klosinski, B., Passie, T., & Brenneisen, R. (2014). Safety and efficacy of lysergic acid diethylamide-assisted psychotherapy for anxiety associated with life-threatening diseases. The Journal of nervous and mental disease, 202(7), 513.

Gearin, A. K. (2016). Good mother nature: ayahuasca neoshamanism as cultural critique in Australia. In The world ayahuasca diaspora (pp. 143-162). Routledge.

Gershon, M. (2004). serotonin receptors and transporters—roles in normal and abnormal gastrointestinal motility. Alimentary pharmacology & therapeutics, 20, 3-14.

Gilbert, P. (2009). Introducing compassion-focused therapy. Advances in psychiatric treatment, 15(3), 199-208.

Grawe, K. (2004). Psychological therapy. Hogrefe Publishing.

Harris, R., & Gurel, L. (2012). A study of ayahuasca use in North America. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 44(3), 209-215. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/02791072.2012.703100

Hsieh, H.-F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative health research, 15(9), 1277-1288.

Jørgensen, C. R. (2006). Disturbed sense of identity in borderline personality disorder. Journal of Personality Disorders, 20(6), 618-644.

Kaufman, R. (2015). How might the ayahuasca experience be a potential antidote to Western hegemony: A mixed methods study Fielding Graduate University].

Kavenská, V., & Simonová, H. (2015). Ayahuasca Tourism: Participants in Shamanic Rituals and their Personality Styles, Motivation, Benefits and Risks [journal article]. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 47(5), 351-359. https://doi.org/10.1080/02791072.2015.1094590

Kjellgren, A., Eriksson, A., & Norlander, T. (2009). Experiences of encounters with ayahuasca—“the vine of the soul”. Journal of psychoactive drugs, 41(4), 309-315.

Küsters, I. (2009). Narrative Interviews: Grundlagen und Anwendungen. Springer.

Lafrance, A., Loizaga-Velder, A., Fletcher, J., Renelli, M., Files, N., & Tupper, K. W. (2017). Nourishing the spirit: exploratory research on ayahuasca experiences along the continuum of recovery from eating disorders. Journal of psychoactive drugs, 49(5), 427-435.

Lafrance, A., Renelli, M., Fletcher, J., Files, N., Tupper, K. W., & Loizaga-Velder, A. (2021). Ayahuasca as a healing tool along the continuum of recovery from eating disorders. In Ayahuasca Healing and Science (pp. 189-208). Springer.

Liester, M. B., & Prickett, J. I. (2012). Hypotheses regarding the mechanisms of ayahuasca in the treatment of addictions. Journal of psychoactive drugs, 44(3), 200-208.

Loizaga-Velder, A. (2013). A psychotherapeutic view on therapeutic effects of ritual ayahuasca use in the treatment of addiction. MAPS Bulletin, 23(1), 36-40.

Loizaga-Velder, A., & Verres, R. (2014). Therapeutic Effects of Ritual Ayahuasca Use in the Treatment of Substance Dependence—Qualitative Results. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 46(1), 63-72. https://doi.org/10.1080/02791072.2013.873157

Luna, L. E. (1986). Vegetalismo: shamanism among the mestizo population of the Peruvian Amazon (Vol. 27). Almqvist & Wiksell International Stockholm.

MacRae, E. (2004). The ritual use of ayahuasca by three Brazilian religions. Drug Use and Cultural Contexts Beyonde the West. Free Association Books, London, 27-45.

Maia, L. O., Daldegan-Bueno, D., & Tofoli, L. F. (2021). The ritual use of ayahuasca during treatment of severe physical illnesses: a qualitative study. Journal of psychoactive drugs, 53(3), 272-282.

Nielson, J. L., & Megler, J. D. (2014). Ayahuasca as a candidate therapy for PTSD. In The therapeutic use of ayahuasca (pp. 41-58). Springer.

Owen, J., Adelson, J., Budge, S., Wampold, B., Kopta, M., Minami, T., & Miller, S. (2015). Trajectories of change in psychotherapy. Journal of clinical psychology, 71(9), 817-827.

Palhano-Fontes, F., Barreto, D., Onias, H., Andrade, K. C., Novaes, M. M., Pessoa, J. A., Mota-Rolim, S. A., Osório, F. L., Sanches, R., & Dos Santos, R. G. (2019). Rapid antidepressant effects of the psychedelic ayahuasca in treatment-resistant depression: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Psychological medicine, 49(4), 655-663.

Passie, T., Emrich, H. M., Karst, M., Brandt, S. D., & Halpern, J. H. (2012). Mitigation of post‐traumatic stress symptoms by Cannabis resin: A review of the clinical and neurobiological evidence. Drug testing and analysis, 4(7-8), 649-659.

Patton, M. Q. (2002). Two decades of developments in qualitative inquiry: A personal, experiential perspective. Qualitative social work, 1(3), 261-283.

Paulus, M. P., Stewart, J. L., & Haase, L. (2013). Treatment approaches for interoceptive dysfunctions in drug addiction. Frontiers in psychiatry, 4, 137.

Perkins, D., Opaleye, E. S., Simonova, H., Bouso, J. C., Tófoli, L. F., GalvÃo‐Coelho, N. L., Schubert, V., & Sarris, J. (2021). Associations between ayahuasca consumption in naturalistic settings and current alcohol and drug use: Results of a large international cross‐sectional survey. Drug and Alcohol Review.

Perkins, D., Ruffell, S., Day, K., Pinzon, D., & Sarris, J. (2022). Psychotherapeutic and neurobiological processes associated with ayahuasca’s mental health and wellbeing outcomes: a proposed model and implications for therapeutic use.

Perkins, D., Sarris, J., Rossell, S., Bonomo, Y., Forbes, D., Davey, C., Hoyer, D., Loo, C., Murray, G., & Hood, S. (2021). Medicinal psychedelics for mental health and addiction: Advancing research of an emerging paradigm. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 0004867421998785.

Perkins, D., Schubert, V., Simonová, H., Tófoli, L. F., Bouso, J. C., Horák, M., Galvão-Coelho, N. L., & Sarris, J. (2021). Influence of context and setting on the mental health and wellbeing outcomes of ayahuasca drinkers: results of a large international survey. Frontiers in pharmacology, 12, 469.

Perry, J. C., & Bond, M. (2012). Change in defense mechanisms during long-term dynamic psychotherapy and five-year outcome. American Journal of Psychiatry, 169(9), 916-925.

Reinhardt, K. M., Zerubavel, N., Young, A. S., Gallo, M., Ramakrishnan, N., Henry, A., & Zucker, N. L. (2020). A multi-method assessment of interoception among sexual trauma survivors. Physiology & Behavior, 226, 113108.

Renelli, M., Fletcher, J., Loizaga-Velder, A., Files, N., Tupper, K., & Lafrance, A. (2018). Ayahuasca and the Healing of Eating Disorders. In Embodiment and Eating Disorders (pp. 214-230). Routledge.

Renelli, M., Fletcher, J., Tupper, K. W., Files, N., Loizaga-Velder, A., & Lafrance, A. (2020). An exploratory study of experiences with conventional eating disorder treatment and ceremonial ayahuasca for the healing of eating disorders. Eating and Weight Disorders-Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity, 25(2), 437-444.

Riba, J., Romero, S., Grasa, E., Mena, E., Carrió, I., & Barbanoj, M. J. (2006). Increased frontal and paralimbic activation following ayahuasca, the pan-Amazonian inebriant. Psychopharmacology, 186(1), 93-98.

Roseman, L., Haijen, E., Idialu-Ikato, K., Kaelen, M., Watts, R., & Carhart-Harris, R. (2019). Emotional breakthrough and psychedelics: Validation of the Emotional Breakthrough Inventory. Journal of psychopharmacology, 33(9), 1076-1087.

Roseman, L., Nutt, D. J., & Carhart-Harris, R. L. (2018). Quality of acute psychedelic experience predicts therapeutic efficacy of psilocybin for treatment-resistant depression. Frontiers in pharmacology, 8, 974.

Rush, B., Marcus, O., García, S., Loizaga-Velder, A., Loewinger, G., Spitalier, A., & Mendive, F. (2021). Protocol for Outcome Evaluation of Ayahuasca-Assisted Addiction Treatment: The Case of Takiwasi Center. Frontiers in pharmacology, 12, 1203.

Russ, S. L., Carhart-Harris, R., Maruyama, G., & Elliott, M. (2019). Replication and extension of a model predicting response to psilocybin. Psychopharmacology, 236(11), 3221-3230.

Safran, J., & Segal, Z. V. (1996). Interpersonal process in cognitive therapy. Jason Aronson, Incorporated.

Sarris, J., Perkins, D., Cribb, L., Schubert, V., Opaleye, E., Bouso, J. C., Scheidegger, M., Aicher, H., Simonova, H., & Horák, M. (2021). Ayahuasca use and reported effects on depression and anxiety symptoms: an international cross-sectional study of 11,912 consumers. Journal of Affective Disorders Reports, 4, 100098.

Schreier, M. (2012). Qualitative content analysis in practice. Sage publications.

Shanon, B. (2002). The antipodes of the mind: Charting the phenomenology of the ayahuasca experience. Oxford University Press on Demand.

Shanon, B. (2014). Moments of insight, healing, and transformation: A cognitive phenomenological analysis. In The therapeutic use of ayahuasca (pp. 59-75). Springer.

Soler, J., Elices, M., Franquesa, A., Barker, S., Friedlander, P., Feilding, A., Pascual, J. C., & Riba, J. (2016). Exploring the therapeutic potential of Ayahuasca: acute intake increases mindfulness-related capacities. Psychopharmacology, 233(5), 823-829.

Tafur, J. (2017). Fellowship of the River: A Medical Doctor’s Exploration Into Traditional Amazonian Plant Medicine. Espiritu Books.

Thomas, G., Lucas, P., Capler, N. R., Tupper, K. W., & Martin, G. (2013). Ayahuasca-assisted therapy for addiction: results from a preliminary observational study in Canada. Curr Drug Abuse Rev, 6(1), 30-42.

Timmermann, C., Roseman, L., Williams, L., Erritzoe, D., Martial, C., Cassol, H., Laureys, S., Nutt, D., & Carhart-Harris, R. (2018). DMT models the near-death experience. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1424.

Van der Kolk, B. (2014). The body keeps the score: Mind, brain and body in the transformation of trauma. Penguin UK.

Wang, X., Wu, Q., Egan, L., Gu, X., Liu, P., Gu, H., Yang, Y., Luo, J., Wu, Y., & Gao, Z. (2019). Anterior insular cortex plays a critical role in interoceptive attention. Elife, 8, e42265.

Watts, R., Day, C., Krzanowski, J., Nutt, D., & Carhart-Harris, R. (2017). Patients’ accounts of increased “connectedness” and “acceptance” after psilocybin for treatment-resistant depression. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 57(5), 520-564.

Weiss, B., Miller, J. D., Carter, N. T., & Campbell, W. K. (2021). Examining changes in personality following shamanic ceremonial use of ayahuasca. Scientific reports, 11(1), 1-15.

Wiebking, C., de Greck, M., Duncan, N. W., Tempelmann, C., Bajbouj, M., & Northoff, G. (2015). Interoception in insula subregions as a possible state marker for depression—an exploratory fMRI study investigating healthy, depressed and remitted participants. Frontiers in behavioral neuroscience, 9, 82.

Winkelman, M. (2014). Psychedelics as medicines for substance abuse rehabilitation: evaluating treatments with LSD, Peyote, Ibogaine and Ayahuasca. Current Drug Abuse Reviews, 7(2), 101-116.

Take a minute to browse our stock:

Did you enjoy reading this article?

Please support Chacruna's work by donating to us. We are an independent organization and we offer free education and advocacy for psychedelic plant medicines. We are a team of dedicated volunteers!

Can you help Chacruna advance cultural understanding around these substances?