- Mazatec Shamanic Knowledge and Psilocybin Mushrooms - February 10, 2022

- Dream and Ecstasy in Mesoamerican Worldview: An Interview with Mercedes de la Garza - January 27, 2022

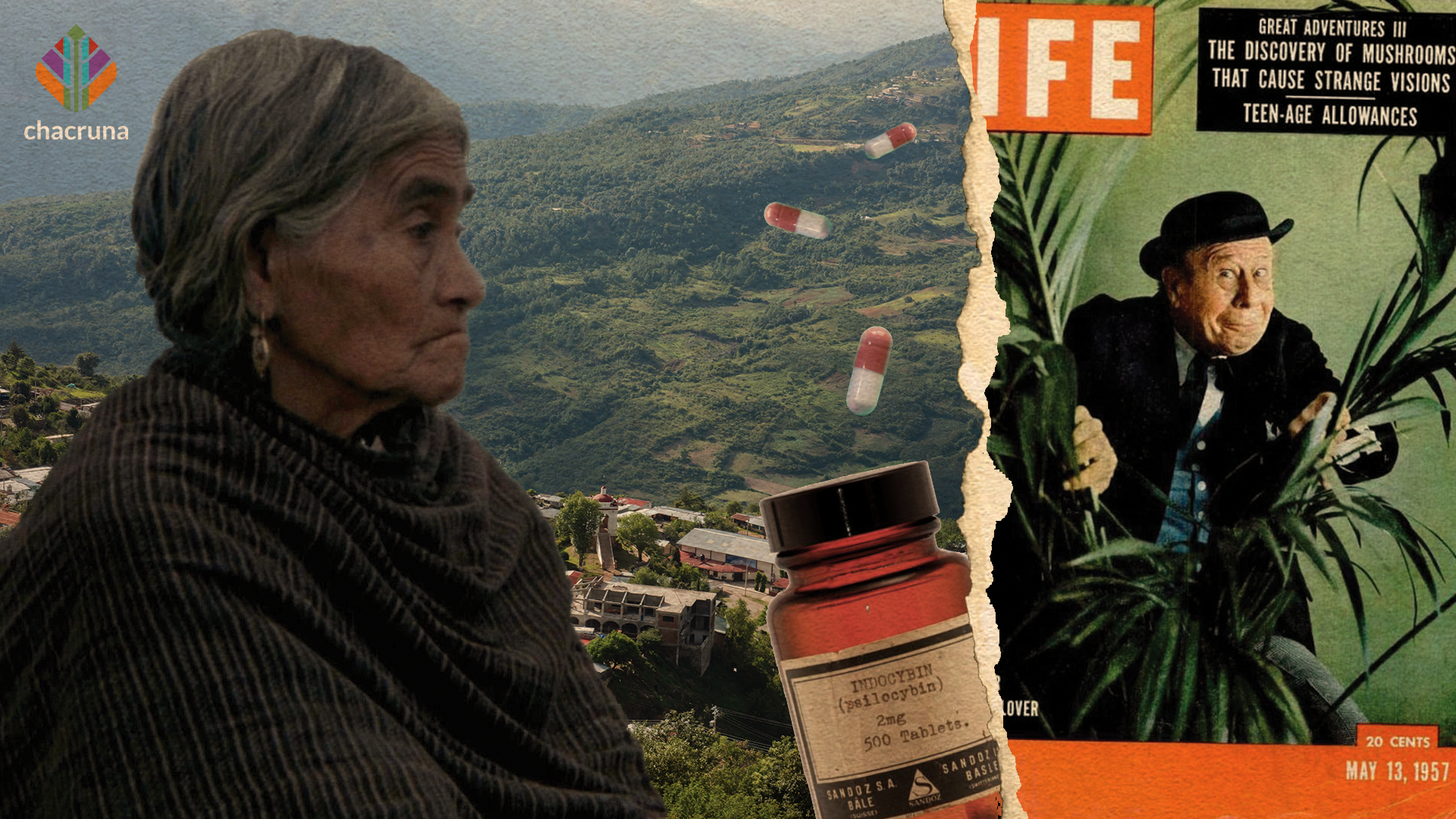

- María Sabina, Mushrooms, and Colonial Extractivism - May 27, 2021

“Who was María Sabina?”

“What kind of wisdom is necessary to find healing in the sacred mushrooms?”

No doubt these are questions that many people have asked themselves. To satisfy that curiosity, I share with you the ideas and experiences of María Sabina. She is undeniably the best-known Mazatec sage, but despite her notoriety she remains poorly understood.

Archaeological evidence and historical sources have demonstrated how Maya, Mixtec, and Aztec civilizations used sacred mushrooms.

Indigenous knowledge about mushrooms is not a pearl of isolated or fortuitous wisdom, but is deeply rooted in ancient Mesoamerican tradition. Archaeological evidence and written historical sources have demonstrated the use of sacred mushrooms by the Maya, Mixtec, and Aztec civilizations.

The Encounter with the Sacred Mushrooms

María Sabina’s first encounter with sacred mushrooms occurred when she was six or seven years old (circa 1900) when one of her uncle’s became ill. To cure him, his family called for a sage (Chotá-a-Tchi-née). This physician-sage had the power to diagnose the sick person, to whom he would feed several pairs of mushrooms. The mushrooms were distributed in pairs to represent the idea of duality and the archetype of the primordial couple. The purpose of having the patient ingest the mushrooms is to learn the origin of his condition so the patient can contribute to the healing process. “A Mazatec ‘shaman’ guides through prayers and chants the one who has decided to ‘realize’ the cause of his ills, and to watch over the good development of the ritual.”

The physician-sage performed a ceremony or “velada” to cure María Sabina’s uncle. She watched as he lit the candles and spoke with the “guardians of the hills” and the “guardians of the springs.” She saw how he distributed the mushrooms among the adults and her uncle. Once in complete darkness, she heard the wise man talk and talk and sing, although it was different from the language he used every day.

Mountains, springs, and plants are endowed with life and personality. Therefore, they are sacred entities with which it is possible to communicate through a ritual language.

These cultural traits belong to the ancient Mesoamerican tradition, which recognizes that the mountains, springs, and plants are endowed with life and personality. They are sacred entities with which it is possible to communicate through a ritual language.

A few days after the healing ceremony, María Sabina was with her sister María Ana tending the family’s chickens to protect them from foxes. Sitting under a tree, she recognized some mushrooms just like the ones eaten by the physician-sage who cured her uncle, and little by little, she began to gather them.

On that first occasion, she ingested the sacred mushrooms together with her sister. After experiencing some dizziness, both girls began to cry; however, once the dizziness disappeared, they both felt fine and were very happy.

María Sabina reports that she felt a new lease on life. In the following days, she says that when they felt hungry, they ingested the mushrooms and felt a full stomach and a happy spirit.

Together with her sister, they continued to eat the mushrooms as they went into the bush. Sometimes their mother or grandparents would find the girls lying down or kneeling. Then, finally, the adults would pick up the girls and take them home. Still, they were never scolded or beaten for eating the sacred mushrooms because the Mazatec people knew it was not good to scold people who had ingested them. After all, it can provoke mixed feelings in them. For example, they may feel that they are going crazy.

The Encounter with the Principal Beings

It was not until she was widowed for the first time that María Sabina got closer to the wisdom of the sacred mushrooms. During the first years of her widowhood, she began to experience discomfort in her waist and hips due to childbirth. She decided to retake the sacred mushrooms to cure herself. However, the decisive moment for reaffirming her vocation was when her sister María Ana became ill. Among the most severe symptoms were pains and spasms in the belly. To relieve her, she called other wise men and healers, but these efforts were unsuccessful.

María Sabina knew that the Mazatecs used sacred mushrooms to alleviate illnesses, so she decided to do the ritual herself. According to testimony recounted by Mazatec writer Álvaro Estrada, she said: “To her, I gave three pairs. I ate many, to give me immense power. I can’t lie, I must have eaten thirty pairs of derrumbe mushrooms.” According to scientific literature, contemporary Mazatecs know and use at least ten different species of psychoactive mushrooms. The most well known are: “derrumbe” (psilocibe caerulescens) and “pajarito” (psilocibe mexicana).

Undoubtedly, this experience was crucial because, in addition to achieving the purpose of relieving her sister, María Sabina had a vision in which six to eight characters appeared that inspired tremendous respect in her. “I knew they were ‘the Principal Beings’ my ancestors were talking about,” she stated.

Ancestors are the bearers of knowledge, wisdom, and experience for Indigenous peoples. Consequently, they are the front line of teachers, facilitators, and guides, and are distinguished for having left a legacy. In the case of María Sabina, her legacy is directly related to the power of healing with the help of sacred mushrooms.

The revelation that occurred during that ceremony would be decisive in consolidating María Sabina’s vocation, as the news of her sister’s healing spread among the inhabitants of Huautla.

A remarkable fact is that this legacy of wisdom appeared to María Sabina in the form of a book. According to María Sabina’s testimony, the Principal Beings surrounded a table on which an open book appeared, which grew to the size of a person. It was white, so white that it glowed, and on its pages were letters. It was not just any book, as Estrada reports: “One of the Principal Beings spoke to me and said: María Sabina, this is the Book of Wisdom. It is the Book of Language. All it contains is for you. The Book is yours, take it to work with.”

This revelation was decisive in consolidating María Sabina’s vocation. The news of her sister’s healing spread among the inhabitants of Huautla, the village where she lived, who sought her out more and more frequently to help them heal their sick family members.

Another remarkable aspect of María Sabina’s story is her recognition of Western medicine. For her, there was no opposition between traditional medicine and Western medicine, but rather a complementary relationship. She also held this to be the case with the spirituality coming from the Mesoamerican tradition and the tradition coming from Christianity. On one occasion María Sabina was shot twice and was taken to the village doctor, a young man called Salvador Guerra. He used anesthesia and removed the bullets, she was amazed and grateful to the doctor, and they later became friends, and she even performed a mushrooms ceremony for him.

Discover Indigenous Reciprocity Initiative of the Americas

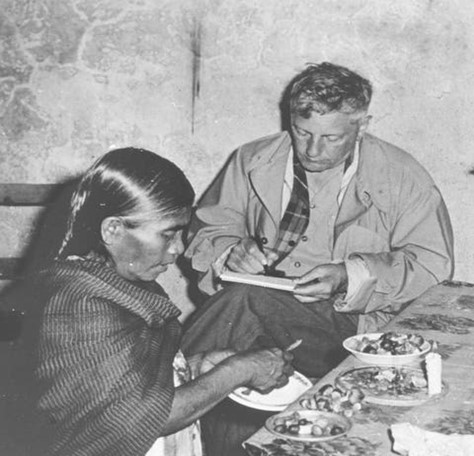

The Encounter with Robert Gordon Wasson

It was her prestige within her community that led to María Sabina’s encounter with Robert Gordon Wasson in 1955. Wasson had been in Oaxaca before, and even to Huautla inquiring about the ritual uses of sacred mushrooms. Their encounter marked a critical moment for studying and understanding sacred mushrooms’ ritual and therapeutic uses.

In both writings for a general audience and in scientific literature of Western culture, there was a belief that these rituals had disappeared with colonization, which was inaccurate. That is why the meeting between María Sabina and Wasson is of particular significance. According to Wasson’s testimony: “There is no indication that any white man has ever attended a session such as the one we are about to describe, nor has he ever consumed the sacred mushrooms under any circumstances.”

In this encounter, it is worth highlighting the asymmetry of power. Wasson was a banker who became vice president of J.P. Morgan, with abundant resources to finance his expeditions. At the same time, María Sabina was a recognized sage in her community. Still, she did not charge a fixed amount of money when she performed her “ceremonies” with sacred mushrooms. Instead, she was under pressure to accept to meet with Gordon Wasson by the municipal trustee of Huautla. In an interview with Alberto Ongaro in 1971, Wasson admitted that the Mazatec sage had been asked to perform the ceremony by the trustee, Don Cayetano. She felt she had no choice. “I should have said no.”

“The encounter between María Sabina and Robert Gordon Wasson represents one of the most critical events in the history of research on the uses of psychedelic plants.”

The pressure put on María Sabina was later corroborated in an interview she gave to Álvaro Estrada in 1976: “It is true that before Wasson, no one spoke so freely about children [sacred mushrooms]. None of our people revealed what they knew about this matter. But I obeyed the municipal trustee. However, if the foreigners had arrived without any recommendation, I would also have shown them my wisdom because there is nothing wrong.”

The encounter between María Sabina and Robert Gordon Wasson represents one of the most critical events in the history of research on the uses of psychedelic plants. Mainly because of its cultural repercussions, which are far from being understood or even acknowledged. Their encounter represents an opportunity to learn about the scope and depth of the wisdom of the Indigenous peoples whom María Sabina’s gift represented. It also provides a chance to reflect on some ethical aspects, such as cultural extractivism, that a decolonial approach cannot leave aside.

Their meeting also gives us an opportunity to reflect on the role of women in psychedelic research, notably the frequently overlooked expertise of Valentina Pavlovna Wasson. She earned a PhD and had a broad knowledge in the field of mycology. Unfortunately, she was not present in the first encounter with María Sabina according to the available information. In her This Week magazine article in 1957, Valentina only briefly mentioned her husband’s encounter with a “shaman,” and her goal was to describe the mushrooms experience in a non-ceremonial context. Furthermore, due to Valentina’s premature death in 1958 is highly possible that these women never met.

It is essential to insist on historical reparations for Indigenous communities for the use of mushrooms.

Perhaps above all, their meeting exhibits an asymmetry of power between the former J.P. Morgan vice-president banker and an Indigenous woman. Although she surpassed him in wisdom, she did not have the same recognition during his lifetime. While Wasson obtained recognition, prestige, and worldwide fame for “discovering” the sacred mushroom, María Sabina lived with the stigma of “revealing” their secrets to an outsider. There was such anger towards her in her community; some unknown people burned her house; a drunk man murdered her son. Years later, in 1985, she died in impoverished conditions, which did not reflect her contributions to the knowledge of psychedelic plants. That is why it is essential to insist on “historical reparations” for the expropriation of mushrooms from Indigenous communities, as Mazatec researcher Osiris García Cerqueda has proposed.

Recognizing the “colonial traces” in the psychedelic renaissance is essential to reflect on these persistent ethical issues, which should not be forgotten or left aside. Confronting these historical legacies is necessary to reverse the undesirable effects of discrimination, cultural appropriation, and lack of recognition.

It is no exaggeration to say that from the perspective of Indigenous peoples, psychedelic research on the therapeutic properties of psilocybin, and the development of related pharmaceuticals have a history linked to extractivism, cultural appropriation, bio-piracy, and colonization.

Let this small text serve as a tribute and recognition of the wise women of all of Mexico’s Indigenous peoples.

Take a minute to browse our stock:

Did you enjoy reading this article?

Please support Chacruna's work by donating to us. We are an independent organization and we offer free education and advocacy for psychedelic plant medicines. We are a team of dedicated volunteers!

Can you help Chacruna advance cultural understanding around these substances?