Stop us if you’ve heard this one: ambitious, brave, and pioneering white man travels to Mexico in the 1950s and is invited to a mushroom ceremony with a curandera. He has a profound personal experience and brings his account of this adventure back to a major publication in the United States, heralding the introduction of the psilocybin mushroom to North America and the world.

For those who regularly engage with research in the field of psychedelics, we have likely all heard this version of the story of R. Gordon Wasson a hundred times. Except we keep telling an incomplete story, again and again… until recently. Scholars are just beginning to pay more attention to the women behind these stories too.

Our Collective Blind Spots

This mis-telling happened recently (and ironically) in an article on the importance of fairness and inclusion in the psychedelic renaissance. Specifically, while highlighting the often under-cited contributions of Mazatec native healer, María Sabina, Gordon Wasson is nevertheless credited as “the most notable Westerner to intentionally ingest psilocybin in Mexico” as well as the only author of the book Mushrooms, Russia, and History.

In fact, Gordon’s wife, Dr. Valentina “Tina” Pavlovna Wasson, had as much—if not more—influence in bringing the psilocybin mushroom to the attention of North Americans.

Let’s Talk About Dr. Valentina Wasson

In many ways, the stories we tell around R. Gordon Wasson and other “founding fathers” of psychedelic studies are universally accepted as canon within the psychedelic community. But when we accept repetition over rigor and fail to question the stories we tell, we fall prey to the same misogynistic assumptions of the time that made figures like Dr. Valentina Wasson invisible to researchers, writers, and historians in the first place.

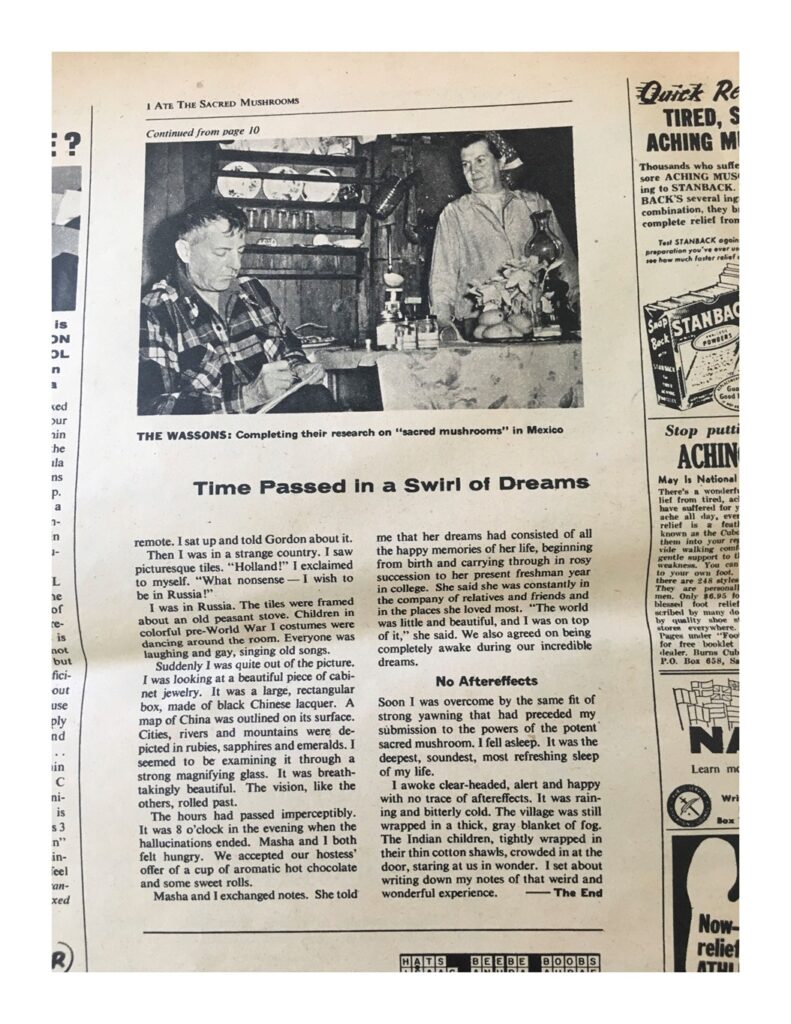

Valentina was a pediatrician and scientist, and a passionate mycology enthusiast—a hobby she had cultivated as a child in Russia. She was also a prolific enthomycologist and researcher. The “real” story of the West’s “discovery” of psilocybin is that after Valentina had led several previous expeditions to research traditional uses of mushrooms in Mexico, María Sabina introduced Valentina and her husband (who was a banker, not a scientist by trade) to her psilocybin mushroom-based practice. The Wassons together gathered mushroom spores during this visit, which were subsequently cultivated and analyzed by psychedelic researcher and chemist Albert Hofmann, thereby directly facilitating his isolation of the psilocybin molecule.

Valentina developed a deep professional and personal passion for the psilocybin mushroom, and she made important and influential contributions to its popularization across the Western world.

Valentina developed a deep professional and personal passion for the psilocybin mushroom, and she made important and influential contributions to its popularization across the Western world, such as her belief that psilocybin could be used for therapeutic purposes, including to support the dying process, another insight that puts her ahead of her time.

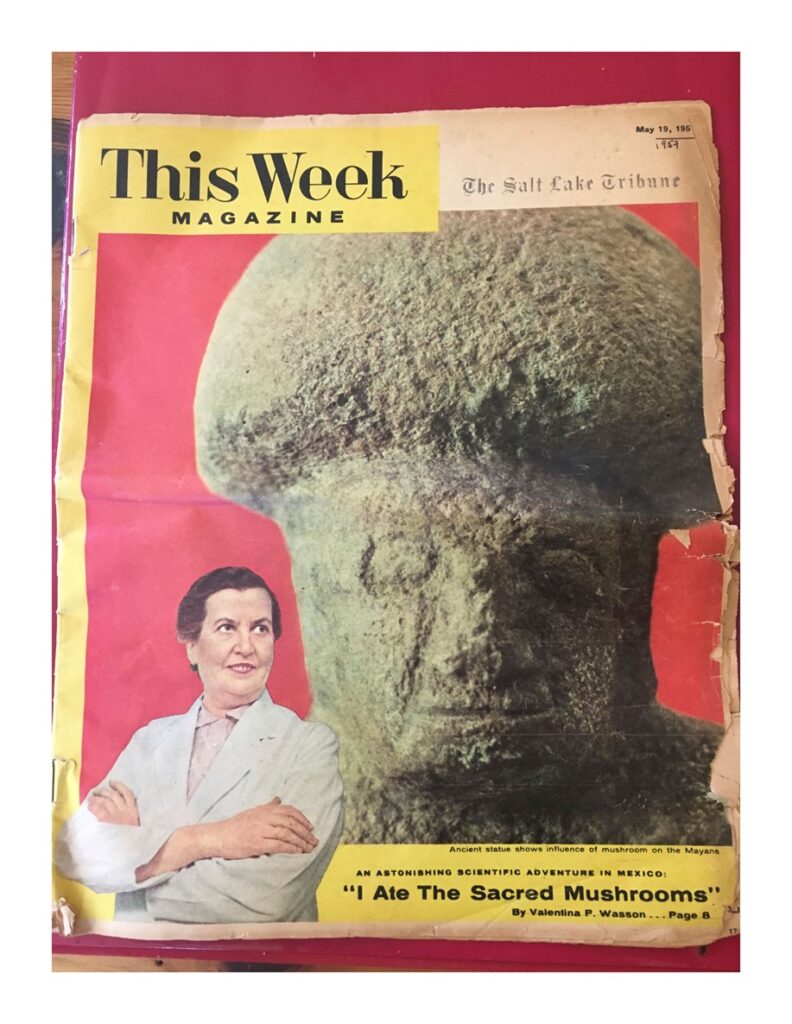

While we update this story, let’s clear up two other often-overlooked misattributions: Gordon did indeed write up his much-cited experiences in a famous Life Magazine article entitled “Seeking the Magic Mushroom.” However, Valentina’s personal account was also published just a few days later in a very popular magazine at the time, called This Week. This Week was a nationally syndicated Sunday magazine supplement that was included in American newspapers between 1935 and 1969.

At its peak in 1963, This Week was distributed with the Sunday editions of 42 newspapers for a total circulation of 14.6 million. This wide public exposure to her account of their time in Mexico shows that Valentina’s contributions were not overlooked at the time—she had a voice and she was using it. Instead, that voice was not given an ongoing place in the collective consciousness of psychedelic studies, and she has been largely forgotten by those who came after.

The second misattribution relates to the omission of her written contributions to the field, as it was Valentina who was the ethnomycology expert, and in fact the lead author of the two-volume text, Mushrooms, Russia, and History, not her husband Gordon, as is frequently cited. The books include a dense and vibrant account of the world of mushrooms in Russia and eastern Europe, weaving local mycology and botany with historically significant myths and historical events in the region. In Volume II of the collection, Valentina also details their experience in Mexico, including pictures and art from their visit. These books capture Valentina’s life-long passion for mushrooms, and honor the influence her fungi-filled Russian childhood had on her important contributions to the popularization of psilocybin mushrooms and growth of the psychedelic field.

Join us at Sacred Plants in the Americas II

Why Correct Attribution Matters

The prevalence and problematic legacy of these oversights and misattributions is something we should all be working to dismantle. Unfortunately, while Gordon is lionized in the story of psychedelic history, Dr. Valentina Wasson and her many accomplishments are forgotten, obscured, and pushed into the background, much like many other women of this time.

The reality for those doing research in this space is that it is simply easier to find references about white men—and in this case, this evidentiary bias has resulted in an inaccurate and marginalizing oversight that has been replicated hundreds of times in academic articles and research.

The reality for those doing research in this space is that it is simply easier to find references about white men—and in this case, this evidentiary bias has resulted in an inaccurate and marginalizing oversight that has been replicated hundreds of times in academic articles and research. The phenomenon of being obscured in the research is well-documented among many key female commentators in the psychedelic movement. And as the case of Valentina shows us, we can and must do better.

The implications of this oversight—and many more like it—should not be taken lightly. Valentina’s story is similar to many dozens of marginalized people whose contributions have been undervalued and underreported in the literature and in popular culture around psychedelics. As the psychedelic renaissance unfolds and as more people learn about psychedelics, it is essential that we build a collective understanding and awareness of the diversity and complexity that has led us to where we are today.

As Valentina’s story shows, those of us committed to building and growing an inclusive psychedelic movement have a collective responsibility to ensure that the voices and contributions of historically marginalized groups are given equal and enthusiastic place in the present. Her story also shows us that these influential forgotten figures of the past should be remembered and celebrated for their contributions to this moment, and to the inclusive and vibrant future we are creating together. Psychedelic work is most impactful when it embraces the inherent diversity and complexity of the journey.

In addition, Valentina’s story reminds us that you never know where your passions will lead you—or lead others. Valentina Wasson spent her childhood in Russia loving mushrooms, and she nurtured that love throughout her life. At its core, it is that simple, earnest childhood passion that changed the world for all of us. Her story therefore also shows us the power of following our life’s passion with humility, curiosity, and an open heart. And this is a story that is definitely worth remembering.

Psychedelics teach people to question what they think they know about themselves and the world around them.

As the psychedelic renaissance unfolds, we can continue to remember what we have forgotten. With intention, we can correct our past mistakes and hold each other and ourselves accountable for the stories we tell as we build the future of psychedelic studies. We must create a strong culture of curiosity: questioning our assumptions with a critical and intersectional eye, and dismantling the stories and practices that keep replicating social and cultural inequalities in psychedelic research and history.

Whether we are talking about the legends we have collectively woven together about the foundations of psychedelic research, or whether we are accounting for race, gender, sexuality and culture in clinical trials, studies and psychedelic community-building in modern times: inclusivity, attribution, and accountability matters.

Psychedelics teach people to question what they think they know about themselves and the world around them. This lesson also applies to the psychedelic community and the stories we tell about ourselves and to each other.

Get curious. Ask questions. Seek truth.

Art by Karina Alvarez.

Take a minute to browse our stock:

Did you enjoy reading this article?

Please support Chacruna's work by donating to us. We are an independent organization and we offer free education and advocacy for psychedelic plant medicines. We are a team of dedicated volunteers!

Can you help Chacruna advance cultural understanding around these substances?