- Why Land and Ecology Matter for Global Psychedelics - January 25, 2024

- Coming of Age in the Psychedelic Sixties - March 15, 2022

- Psychedelics, the War on Drugs, and Violence in Latin America - March 10, 2022

Biographical essay dedicated to the interconnected paths of Juan Negrín, Sasha Shulgin and Silviano Camberos.

The texture, color, and flower of the peyote remain a vivid childhood memory.

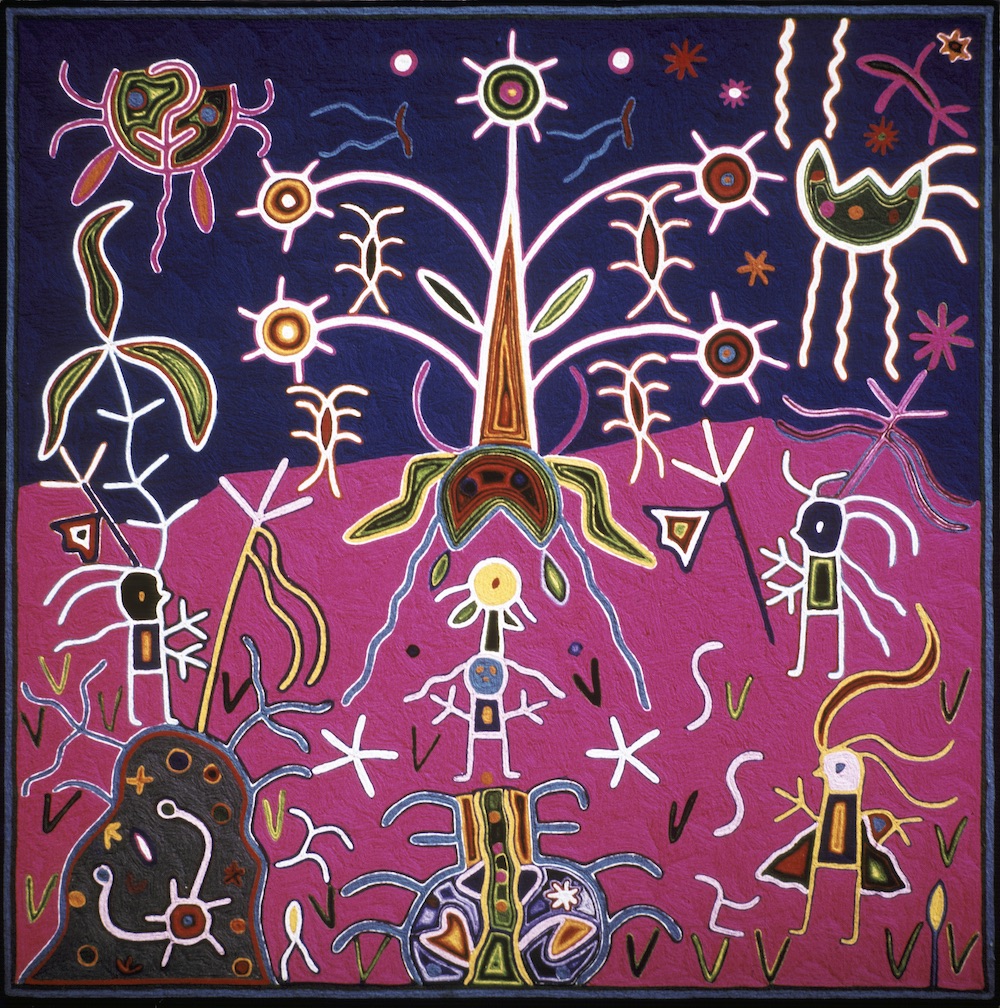

I would lay, legs up, on the couch observing José Benítez Sánchez’s, Tatei ‘Atsinari, Our Mother the Coiled Serpent of Corn Gruel, while semiconsciously listening to the conversations my father would sustain with our visitors—often on the topic of ethnobotany.

I grew up in a unique household in the context of Guadalajara’s conservative and classist Catholicism. It was a home that was shared with Wixarika families and visitors from different parts of the world who sought to learn a thing or two about one of Mesoamerica’s original and dynamic cultures. My childhood memories are filled with yarn paintings created by the masters of Wixarika art. I would lay, legs up, on the couch observing José Benítez Sánchez’s, Tatei ‘Atsinari, Our Mother the Coiled Serpent of Corn Gruel, while semiconsciously listening to the conversations my father would sustain with our visitors—often on the topic of ethnobotany.

I remember, with intensity how, once peeled, the opaque green of the peyote would turn into a brilliant emerald green.

My parents met in the San Francisco Bay Area in 1968, both attracted by the cultural opportunities offered by this rebellious region during such a unique time period. My father, Juan Negrín (1945–2015), was born in Mexico City, the child of an American woman and a Spanish exile—a condition that allowed him the privilege to explore the world beyond nationalist boundaries. My mother, Yvonne da Silva, was born in New York, the daughter of other diasporas, principally Azorean-Portuguese via Brazil and Irish via Ohio. My parents’ story, which is interwoven with ethnobotany, begins in this foggy corner of California.

Tatei ‘Atsinari, Our Mother the Coiled Serpent of Corn Gruel by José Benítez Sánchez, 1980, wool yarn on beeswax and wood, 4 ft x 4ft. Negrín Family Collection.

In my home and among our close friends, peyote was a plant that was to be respected with love.

In my home and among our close friends, peyote was a plant that was to be respected with love. Peyote was not fetishized nor was it a dominant topic, but it was a present element.

After my father encountered Wixarika yarn paintings in an exhibit in the Basilica of Zapopan, he began a lengthy and very committed relationship with Wixarika art, culture, and territory. From the beginning of the 1970s onward, he participated in arduous pilgrimages in the Wixarika mountains and, on six occasions, he visited Wirikuta, walking and fasting from the Western Sierra Madre in Jalisco to the sacred land of the peyote in San Luis Potosí.

If one did not walk, fast, and confess one’s missteps collectively, the peyote would discover your mask with a punishment.

If one did not walk, fast, and confess one’s missteps collectively, the peyote would discover your mask with a punishment. As a good existentialist, my father would dedicate weeks to these journeys and their accompanying sacrifices.

Join us at Sacred Plants in the Americas II

As the years passed, new friendships were made through shared links to the study of the medical and social benefits of psychotropic plants. Alexander (Sasha) Shulgin (1925–2014) and Ann Shulgin were among the most emblematic of these friends, whose texts Pihkal: A Chemical Love Story and Thikal explored—based on decades of scientific research—the union between chemistry and the human mind. When my parents returned to live in California during different moments of the 1990s, they began attending “Friday night dinners” where a wide spectrum of erudites of psychotropic plants and psychedelics would gather. Between the libations, the attendees would share personal experiences with plants and new findings. During my adolescent years, the hosts would hire me to clean up the dishes, granting me the opportunity to overhear the guests’ various conversations.

Have you tried peyote? Did your parents give you some when you were little? Did you go to Huichol ceremonies as a child? Did they give you peyote?

What they shared was a profound passion for the intersection between Western and Indigenous scientific knowledge.

The interests that united the students of these plants cannot be reduced to a myopic attraction to psychedelics, as so many have caricaturized. What they shared was a profound passion for the intersection between Western and Indigenous scientific knowledge. Some sought to influence laws that had collapsed plants like peyote with synthetic substances produced for a massive market, while others sought to produce and disseminate greater scientific knowledge on the therapeutic use of these substances. As one could expect, there always was a segment of people that would attend these reunions through their egocentric impulse to speak about their psychedelic “trip.” While they were comical, they have remained the fixed popular image of ungrounded psychodelia.

Peyote was not the only plant. There was also the kieri, known as the Tree of the Wind—from the family of the datura and Solandra, or toloache.

The masterwork by Wixarika artist Guadalupe González Ríos, The Birth of the Kieri, hung on the stairway of our home. This was a plant to fear and the whispers about its power would make me run past the four feet by four feet painting. I even dreaded saying its name. This fearful awe was sustained when several mara’akate (Wixarika shamans) agreed that my father’s epilepsy was associated with his inability to fulfill his duties to the kieri, a plant that my father visited, after Guadalupe asked him to accompany him to visit this plant, which he considered to be his patrón or master. If one did not fulfill one’s duties to the kieri, the plant had the capacity to turn itself into a seductive woman and lead you toward a series of unfortunate events.

The Birth of the Kieri by Guadalupe González Ríos, 1973, wool yarn on beeswax and wood, 4 ft by 4 ft. Collection of Juan and Yvonne Negrín.

My father lay in the garden while the mara’akame conducted a limpia, a cleansing. From his stomach emerged a piece of the kieri. I looked at this tiny piece of root with amazement, understanding that plants had the power for good and for bad.

Throughout the years, I met many people who shared my parents’ enthusiasm and fascination for plants and their medicinal and psychotherapeutic properties. Silviano Camberos Sánchez (1962–2009) was a marvelous doctor and ethnobotanist who began his trajectory as a doctor in the Wixarika communities and later traveled through the Americas to learn about the diverse uses of sacred plants, often alongside Dr. Mark Plotkin. His incorporation of plants and Indigenous medicinal techniques into his practice made him a great doctor.

But other characters had tragic encounters, crossing the world to reach a magical Mexico only to remain on the “trip,” terrified, confused, and alone.

Undoubtedly, the debate over mining concessions in the sacred place of pilgrimage of Wirikuta has captivated the attention of many peyote enthusiasts who have allied themselves to the struggle to protect this cactus that is endemic to the Chihuahuan Desert. With the context of contemporary battles over the political, economic, and cultural status of sacred plants in mind, it is worth taking a pause to reflect on the groundbreaking work carried out by my parents’ generation in giving life to global conversations about these plants. It is to them that I dedicate this brief reflection.

A Mystical Communication with the Kieri”, yarn painting Guadalupe González Ríos, 1973.

Courtesy of Negrín Family Collection. Art by Mariom Luna.

—-

Note: this text appeared originally in Spanish in 2015 in the blog Drugs, Policy and Culture. This blog was transformed into Chacruna Latinoamérica in 2020.

Take a minute to browse our stock:

Did you enjoy reading this article?

Please support Chacruna's work by donating to us. We are an independent organization and we offer free education and advocacy for psychedelic plant medicines. We are a team of dedicated volunteers!

Can you help Chacruna advance cultural understanding around these substances?