- What I Learned Treating 400+ Patients with Ibogaine and Ayahuasca - March 13, 2017

Since the middle of the 90s, there has been a renewed interest in the possible positive effects of many different plants and substances such as LSD, “magic” mushrooms and psilocybin, ayahuasca or iboga. Many new and rigorous scientific studies have been showing promising evidence that those substances are suitable for the treatment of many diseases and disorders such as obsessive-compulsive disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, substance abuse or even depression.1 With so many possibilities, we could easily assume that psychedelics are the new panacea capable of curing any ailment. But, what is this cure? How does it happen? How similar are those curing processes to those of conventional medicine?

Ayahuasca ready to be boiled. Photo: Awkipuma

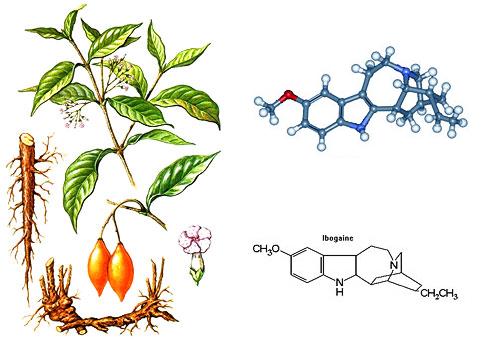

I’m a psychologist in Brazil and, after more than ten years working with homeless crack-cocaine users, I got involved with ayahuasca and ibogaine treatments, curious about what they could offer. Could these substances help my patients, who I have been struggling so hard to take care of? Since then, I have studied and assisted a group of recovering homeless individuals using ayahuasca, a brew made with Amazonian plants, most commonly Psychotria viridis and Banisteriopsis caapi. I’ve also treated around 400 patients with problematic drug use by using ibogaine. Ibogaine is a substance derived from the root bark of the African plant iboga (Tabernanthe iboga). Both ayahuasca and ibogaine have intense effects on the user’s perception of the world and oneself.

These substances can be classified in a variety of categories: psychedelics, entheogens, hallucinogens, as well as plant teachers, depending upon how they are used. The ayahuasca treatment I studied integrated the rituals of two traditional ayahuasca cultures; firstly, vegetalismo, with its purges and diets, and also the musical healing rituals of Santo Daime. In this context, the brew is considered a plant teacher: a substance with a spirit that communicates with humanity through its effects. The ibogaine treatment, on the other hand, is much more similar to regular medicine. Ibogaine is extracted from the plant, processed by a pharmaceutical laboratory, and then prescribed by a medical doctor in a hospital.

“Many patients that I’ve given ibogaine to still reported seeing or being visited by the “iboga spirit”; usually an old African woman or ancestral healer”

These contexts affect the use of and understandings of the substances, therefore changing what is experienced by the patient. This is even more evident when comparing different ayahuasca rituals. The same ayahuasca decoction in the context of a Santo Daime ritual, with bright light and everyone singing together—and then in a Shipibo indigenous ritual, in complete darkness, guided only by the curandero’s voice—will elicit a very different experience.

Especially interesting in this complex relationship between setting and experience is the element of mystery. Even within a medical context, and never having heard about the African traditional cults with iboga, many patients that I’ve given ibogaine to still reported seeing or being visited by the “iboga spirit”; usually an old African woman or ancestral healer.

The reports and testimonials about these two substances are very impressive: the intensity of the experiences, as well as the sudden and deep transformations gained through them, attract more users every day; either looking for something new or different, or a spiritual or healing experience. Together with these reports, new scientific research on ayahuasca and iboga shows promising new and effective treatments for problematic drug use and alcoholism.2 There’s also constantly new data to show psychedelic substances use in treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder, tobacco dependence and PTSD.3

In the context of these reports, patients interested in ibogaine treatment often expect a new and powerful medicine. As aspirin reduces fever, they expect that ibogaine will take their drug dependency away; something fast and effective that solves the problem for good. It would be perfect if ibogaine or ayahuasca could cure with the speed of aspirin, and if it could work no matter the setting. With aspirin, it doesn’t matter where one takes it or if one believes in it, it will still reduce fever. With psychedelics, it’s not like that: the patient’s expectancy, his trust in those responsible for the experience, as well as what happens in the surrounding environment, will exert an intense influence on the experience.

These factors not only affect the experience, but also the outcome. The experience with the substance needs to be part of a process in which things happen before and after the experience itself. A recent study developed at the John Hopkins University4 showed the impressive effects of psilocybin sessions in stopping cigarette smoking in patients for more than 6 months. But, psilocybin has this effect when inserted in a process like the one on the study, with sessions of cognitive-behavioral therapy. It’s not as simple as eating psilocybin “magic” mushrooms and then losing the craving to smoke; although it would be wonderful if it were that easy!

“Many patients arrive expecting a “magic pill,” a new medicine that would solve everything for them, and that has a negative effect on their process”

How can an intense psychedelic experience lead to important changes on daily life? For consistent changes, we need to desire them, understand our dynamics, and make an effort to change it. Usually, those kinds of changes are supported in a relationship, be it with a therapist, a doctor, a healer, a shaman, a religious leader, or a group. Each one of the psychedelic substances tested exist within a context: specific ways of understanding the substance use and different ways of dealing with them; sometimes, in a religious, modern or traditional ritual. Those relationships are important for the patient when going through the process, and also to give meaning to the experience.

Iboga plant and Ibogaine molecule. Photo: Samwise

Concerning the ibogaine treatment, many patients arrive expecting a “magic pill,” a new medicine that would solve everything for them, and that has a negative effect on their process. I receive patients in my office before and after they take ibogaine. Most of the times I can clearly see a difference: they are calmer, and it’s easier to face the daily challenges. With a clearer mind, it’s easier to focus on what is important in their lives and there’s a lack of craving. But it doesn’t mean that the addiction is cured, and not all of them can take advantage of these effects to really overcome their problem.

After ibogaine, many patients are aware of all they need to change in their lives; but really changing their habits is usually harder, as it depends on the patients. If the substance had solved everything for them, why change anything else in their routine? Many of them can’t get out of their established routines, and after, they just go on living in the same way: going to the same bars, meeting the same friends, looking for the same types of pleasures, and one day or another they’ll return to problematic drug use. When we need to change, it will always require effort from ourselves, but if we expect for someone or something to solve our problems for us, it will be harder to succeed.

So, despite the increasing interest in ayahuasca, iboga, ibogaine, psilocybin, and other psychedelics in general, those substances, and the experiences they trigger, are still a new and vast continent to be explored. We are only now beginning to understand the complex interactions between psychedelic substances, psychology, and the setting in which people consume the psychedelic substances. It seems that psychedelics function differently from the traditional Western medicine remedies, and may be better understood as a therapeutic tool.

References

- Pollan, Micael 2015. The Trip Treatment in The New Yorker access at http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2015/02/09/trip-treatment

Bogenschutz, M. P., Forcehimes, A. A., Pommy, J. A., Wilcox, C. E., Barbosa, P. C., & Strassman, R. J. (2015). Psilocybin-assisted treatment for alcohol dependence: A proof-of-concept study. J Psychopharmacol, 29(3), 289–299.

Johnson, M. W., Garcia-Romeu, A., & Griffiths, R. R. (2017), Long-term follow-up of psilocybin-facilitated smoking cessation. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse (Epub ahead of print), 43(1), 55–60. PMID:27441452

Mithoefer, M. C., Grob, C. S., & Brewerton, T. D. (2016). Novel psychopharmacological therapies for psychiatric disorders: psilocybin and MDMA Lancet Psychiatry, 3(5), 481–488.

Mithoefer, M. C., Wagner, M. T., Mithoefer, A. T., Jerome, L., & Doblin, R. (2011). The safety and efficacy of +/-3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine assisted psychotherapy in subjects with chronic, treatment-resistant posttraumatic stress disorder: The first randomized controlled pilot study. J Psychopharmacol, 25(4), 439–452.

Moreno, F. A., Wiegand, C. B., Taitano, E. K., & Delgado, P. L. (2006). Safety, tolerability, and efficacy of psilocybin in nine patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry, 67(11), 1735–1740. ↩

- Bogenschutz, M. P., Forcehimes, A. A., Pommy, J. A., Wilcox, C. E., Barbosa, P. C., & Strassman, R. J. (2015). Psilocybin-assisted treatment for alcohol dependence: A proof-of-concept study. J Psychopharmacol, 29(3), 289–299. ↩

- Moreno, F. A., Wiegand, C. B., Taitano, E. K., & Delgado, P. L. (2006). Safety, tolerability, and efficacy of psilocybin in nine patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry, 67(11), 1735–1740. ↩

- Johnson, M. W., Garcia-Romeu, A., & Griffiths, R. R. (2017), Long-term follow-up of psilocybin-facilitated smoking cessation. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse (Epub ahead of print), 43(1), 55–60 ↩

Take a minute to browse our stock:

Did you enjoy reading this article?

Please support Chacruna's work by donating to us. We are an independent organization and we offer free education and advocacy for psychedelic plant medicines. We are a team of dedicated volunteers!

Can you help Chacruna advance cultural understanding around these substances?