It’s Still A Drug War

Like most everyone in the “Just Say No” generation, I was taught to stigmatize and fear all drug users. Fortunately, I grew up with internet access, and no amount of social programming could quash my instinct to peek behind the veils of propaganda and politics. 20 years ago, my activism started after an innocent internet search for cancer cures led me down a rabbit hole to the truth of Anslinger’s paranoid push for marijuana prohibition and Nixon’s violent, conspiratorial drug war.

Among my fellow Drug Policy Reform activists, and the more visionary cannabis industry professionals, there’s a shared understanding that marijuana legalization has been a testing ground for our greater work: ending the global Drug War in its entirety. We’re nearly 10 months into California’s adult-use market, and I’ve found that hindsight is both illuminating and nauseating. Getting this right is unbelievably difficult.

As psychedelic legalization begins to hit its stride, I’ve been compelled to share some insights from the frontlines of cannabis, hoping we might be able to avoid some of the same mistakes. My first impulse was to break down recently enacted cannabis legislation piece by piece, highlighting where specific policies worked or failed. I quickly found there was too much to say, but a singular underlying and critical theme emerged: compassion.

The Heart is a Root

Drug use is culturally dependent. Just like psychedelics, humans use cannabis for everything from therapy and recreation, to improving productivity, personal relationships, and general wellbeing

Drug use is culturally dependent. Just like psychedelics, humans use cannabis for everything from therapy and recreation, to improving productivity, personal relationships, and general wellbeing. Despite this, cannabis legalization efforts always start with medical-only access. For good or ill, psychedelic legalization efforts apparently intend to follow suit.

The United States government has criminalized drug users for generations. But, in 1970, modern drug policy reform efforts organized in opposition to the Controlled Substances Act. The National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws (NORML) launched that same year, signaling the start of organized civic action in pursuit of broader drug policy reform. A social movement emerged.

At times, victory seemed imminent. The Shafer Commission warned where things were headed, but its recommendations to President Nixon were ignored. Instead, he funded the Drug War, targeting “Blacks and anti-war” types. Both camps resisted. By 1988, a federal judge ruled in favor of marijuana as medicine. But, amidst Reagan’s “Just Say No” propaganda, and a CIA-backed crack epidemic, drug policy reform activists saw little progress. Fueled by compassion, activists persevered, though not always with equity in mind.

As the Drug War began dovetailing with the AIDS crisis, social movements converged, it became apparent that a medical model of drug policy was most palatable to a population befuddled by Drug War propaganda. Lacking rigorous studies, proving the case that cannabis had therapeutic capacity was challenging, but not impossible, because drug users had something more powerful for changing opinions: lived experience and anecdotal evidence.

In time, everyone knew someone who found therapeutic benefit from this drug. Eventually, a body of research supported this claim. Empowered by these truths, one of marijuana legalization’s godfathers, Dennis Peron, recognized that decriminalization and medical-only approaches alone couldn’t guarantee access for the suffering. What we needed was an equitable marketplace.

On Compassionate Business Models

Spearheaded by the LGBT community in 1991, Prop P afforded San Franciscan patients the right to access marijuana. In 1996, California passed Proposition 215, “The Compassionate Use Act” and Senate Bill 420, legalizing the production and sale of cannabis for qualified medical conditions. Medical access alone was never the end goal, but one by one, each state began chipping away at this critical baby step. The early nonprofit operations were quite different than the million-dollar showrooms and grow houses of today.

Amid homelessness and neighborhoods impoverished by the racist Drug War, dispensaries offered kindness, humanity, food, clothing, dental care, and acupuncture; even tax-prep services. And for those who couldn’t pay, many offered free cannabis through compassion programs. Dispensaries filled the space between the cracks of our broken social systems. It wasn’t a perfect model, but it taught us something.

We learned that people who use drugs together tend to take care of one another. Once a culture adopts a norm to care for “the least among us,” a true community can form, complete with necessary safety nets. Shared vulnerability, it seems, begets social responsibility. In the face of federal prosecution, DEA raids, and lifetime prison sentences, compassion fueled the medical marijuana movement, and inspired the drug policy reform movement.

If it’s Broke, Don’t Use it

During the AIDS crisis, human compassion catalyzed the medical marijuana movement. Psychedelic research today echoes that pulse

During the AIDS crisis, human compassion catalyzed the medical marijuana movement. Psychedelic research today echoes that pulse. And, while there are a host of reasons behind the therapeutic effects of these drugs, most of these transformative events have occurred outside of a standardized clinical model.

When we try to medicalize therapeutic drug experiences, a doctor’s note can become the difference between a “good” drug user and a “bad” drug user. But, in our broken medical system, medicalizing drug policy is a moral compromise. It redirects the movement, tilting compassion and liberty toward pathology, perpetuating the racist and stigmatizing overtones embedded in Drug War propaganda. This does not echo the compassion that conceived the Drug Policy Reform movement.

Many suffering from conditions that psychedelics address cannot equitably access the United States

For starters, adhering to a medical-only model neglects accessibility issues inherent to obtaining a medical diagnosis. Many suffering from conditions that psychedelics address cannot equitably access the United States’ for-profit health care regime; most specifically, minorities and people of color. And unless one is culturally conditioned to seek mental health treatment, unless one has access to a proper DSM diagnosis, insurance, an appropriate physician/psychiatrist/therapist, they will never see the benefits of these therapeutic drugs .

This confines natural and alternative healthcare in the traps of consumer capitalism, Western medicine, and the bureaucratic and cultural systems that sustain both. If “breakthrough” medicines are not made accessible primarily to those furthest from an access point, then our policies have failed. And if drug policies are removed from the context of the Drug War just so we can push legislation through, we’ve missed the mark entirely.

Illicit drugs can be therapeutic regardless of social acceptance or legal status, and some people who use drugs are understandably wary of Western medical systems. So when we refuse to include all aspects of drug use in the policy conversation, we aren’t ending the Drug War at all. We’re sustaining it.

Why Stigmatizing Human Behavior is Bad Policy

A medical-first drug policy prioritizes access for a specified class of patient. A medical-only approach does so at the expense, degradation, and stigmatization of “recreational” and even “spiritual” users. Both approaches fail to recognize both the definition of “drug” and that there are many paths to wellness. This language manifests in harmful assumptions and ineffective policies that put marginalized communities at greater risk of imprisonment, violence, and cultural erasure. The only ones who seem to benefit immediately from a medical-only model are dominant social groups.

While mainstream American culture grows increasingly supportive of cannabis and psychedelics, it’s helpful to consider how drug policies built around medical-only models actually manifest a false dichotomy between “good” and “bad” drug users. Good drug users are deserving medical patients, going to private healing retreats in South America, and microdosing their way through their second startup. Bad drug users are getting high and partying with their friends, medicating their way through rural America, or sitting inside a prison cell right now.

This is not what progress looks like, and, as new groups begin to consider psychedelics, it provides a harmful example to follow.

Many who use drugs are so conditioned by propaganda, the only way to navigate their internalized stigma is to simultaneously criminalize those who use drugs differently. Such rationalization kicks human compassion through a trapdoor to arrogance, classism, and racism. This fractures solidarity and perpetuates the Drug War culture on a societal level. This is not what progress looks like, and, as new groups begin to consider psychedelics, it provides a harmful example to follow.

Instead of creating a compassionate culture working to end the Drug War in its entirety, what’s left is a culture of competition and the continual abuse of power over marginalized people. Equitable and sustainable drug policy cannot result from a culture. Business, however, can thrive here.

Welcome to Dude Bro Corp. Take a Seat.

I honestly thought our compassionate roots would grow with the cannabis industry once we legalized recreational access for adults in California.

“The Green Rush” has beckoned many to venture out of the safety of their standard stock portfolio, and those that do are not all “heart-driven” humans. The luster of millions is enough to lure the staunchest prohibitionist, even those who have never seen, let alone used, cannabis. As unsavory as these characters are, many activists forget corporate cannabis existed before legalization. The difference was it was championed by activists willing to take bullets while staring down the barrel of a DEA raid because prohibition is an unjust web of lies and violence that must be stopped.

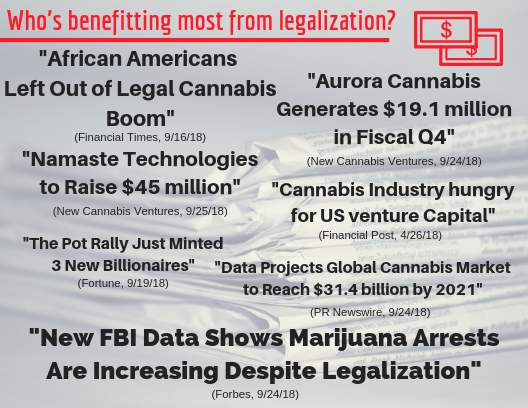

Modern industry professionals are much less committed to the cause. Today, it’s capitalism, not compassion, that attracts new energy and money into the cannabis “industry.” But these new Rules of Engagement, where profit is a legal imperative, changed something. It’s as if the nascent cannabis businesses don’t remember there’s still a Drug War going on outside the convention center. And while the anti-war types can pass as non-combatants in the Drug War, people of color are still being targeted and violated daily.

Activism and business intersect awkwardly, and compassion can be hard to practice, when movements split and competing interests double down. In the realm of California cannabis, I witnessed a community once built around compassion buckle under the weight of consumer capitalism. We’ll be recovering for years, and that’s okay.

If we had more time, maybe we could have been better prepared to fight off the Vikings and vultures waiting in the wings. Maybe we could have carved out better pathways for compassion programs, or mandated corporate social responsibility, or insisted on open-science and shared data and transparency. Some wanted to. Some tried. But it happened so fast, and after all the negotiations, everything came down to a single ballot and a single decision we all had to make individually.

It was never possible to legislate a perfect marketplace in a single action. But what we could do is take a baby step and pass a measure that provides an immediate path out of prison. When compassion is your center, when you remember that prohibition is not a nuisance, but actually, a violent, conspiratorial Drug War, this is not a “compromise”; it’s the right thing do.

A Lesson Learned is Not Worth Repeating

The psychedelic community has its own unique set of challenges. We are rapidly approaching a crossroads the cannabis community now must face every day. To keep psychedelics centered on the compassionate principles of the drug policy reform movement, we, the independent activists, researchers, and scholars may actually want to avoid the example laid out by cannabis legalization efforts.

Medical-only and medical-first approaches might be palatable to prohibitionists, but there is no liberation from the Drug War until all drug users are free. Period. Psychonauts are not morally superior to people who use meth, or alcohol, or heroin. Anyone leading drug policy reform conversations from a platform that suggests otherwise needs to pass the talking stick to a drug policy reformer who leads with compassion. After the war is over, you’ll be free to exercise your superiority complex.

At some point, a market for psychedelics will emerge, and it won’t be perfect. But as long as the most marginalized among us are guaranteed primary access,

At some point, a market for psychedelics will emerge, and it won’t be perfect. But as long as the most marginalized among us are guaranteed primary access, and palatable medical models don’t sacrifice spiritual and recreational drug users in the process, and grassroots activists, researchers, healers, and drug users on the frontlines remember that all of this is occurring in the midst of the Drug War, it shouldn’t be too difficult to make decisions on how we carry ourselves during these final battles.

Will we see a “Rainbow Rush” as venture capitalists privatize research and prepare to market their magic microdose or sexy shaman cruise to an endless supply of American consumers? Will open-science overcome the psychedelic patriarchy, colonization, and neoliberalism? Can compassion guide us through the opioid epidemic and the conclusion of this war?

As mainstream American culture looks on, it’s time to let go of nostalgia for the “psychedelic renaissance” so we may collectively imagine an inclusive and equitable post-prohibition future

Scientists, students, activists, and a massive community of visionary drug users say “yes.” As mainstream American culture looks on, it’s time to let go of nostalgia for the “psychedelic renaissance” so we may collectively imagine an inclusive and equitable post-prohibition future.

Ready to help end the Drug War? Visit Students for Sensible Drug Policy and The Drug Policy Alliance to learn more.

Note:

Katie Stone was the moderator of the panel “Capitalism’s Systemic Issues: Will They Emerge in Psychedelic Medicine and Practices?” at the conference Cultural and Political Perspectives in Psychedelic Science, a symposium promoted by Chacruna and the East-West Psychology Program at the California Institute of Integral Studies (CIIS), San Francisco, August 18–19, 2018.

Take a minute to browse our stock:

Did you enjoy reading this article?

Please support Chacruna's work by donating to us. We are an independent organization and we offer free education and advocacy for psychedelic plant medicines. We are a team of dedicated volunteers!

Can you help Chacruna advance cultural understanding around these substances?