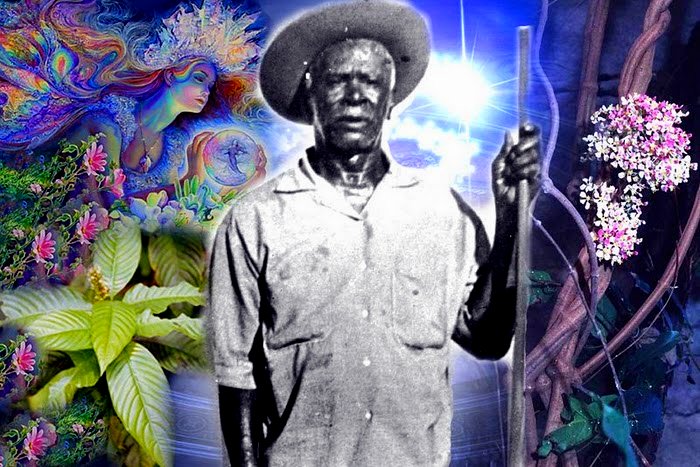

Irineu Serra was a poor migrant from northeastern Brazil who spent many years working in the Amazonian forest. During this time he came across a shaman who gave him ayahuasca to drink, causing him to have many visions among which was one of a woman, initially considered to be a forest spirit and later identified with the Virgin of the Conception.

During many ayahuasca sessions she appeared repeatedly in his visions, teaching him how to use ayahuasca to become a great healer. As part of her instructions, she imparted to him a new religious doctrine based on the ritual taking of ayahuasca. This doctrine continued to be elaborated in visions he kept having for the rest of his life. This then became the basis for his treatment of those who came to him for healing and, after some time, he set up a church in the remote town of Rio Branco in what was then the Brazilian state of Acre.

Among these peoples, psychoactive plants are often called “teacher plants,” and it is considered that they allow the user to gain direct access to the spiritual world and to storehouses of wisdom not otherwise available to them. Thus, it is common for shamans to claim that their knowledge of the healing power of plants and of the correct ways of using them was acquired in dreams or visions produced by the ingestion of these entheogens.

“IT IS COMMON FOR SHAMANS TO CLAIM THAT THEIR KNOWLEDGE OF THE HEALING POWER OF PLANTS AND OF THE CORRECT WAYS OF USING THEM WAS ACQUIRED IN DREAMS OR VISIONS PRODUCED BY THE INGESTION OF THESE ENTHEOGENS.”

One of the most widely used entheogens is ayahuasca. This is a psychoactive brew made from the Bannisteriopsis caapi vine and the Psychotria viridis leaf, which has been used for many purposes by the native inhabitants of western Amazonia since time immemorial. Its psychoactive properties are due to alkaloids such as harmine, d-leptaflorine, DMT, and harmaline, which appear in varying concentrations in the vine and in the leaf. Conceived of as a means of opening human perception to the spiritual world, this brew has been used mainly by Indian and mestizo shamanic healers for the diagnosis and treatment of ailments, divination, hunting, warfare, and even as an aphrodisiac. Although its use probably originated among the inhabitants of the rainforest, ayahuasca was taken to the Andean highlands where it received the name by which it is best known, which means, in Quechua, “vine of the spirits.”

In the last few years, ayahuasca has become the central sacrament of a number of syncretic religions that originated among Amazonian rubber tappers and then spread to the urban middle classes, initially in Brazil, but now reaching several European countries, the US, and even Japan. The oldest of these religions is an eclectic mixture of popular Catholicism, Spiritism, African religiosity, and Indian shamanism known as “Santo Daime,” after the name given to ayahuasca by its founder, Raimundo Irineu Serra (or Mestre Irineu, as he is known).

The followers of this religion maintain that their sacrament is not a drug, but “The Blood of Christ” or “a divine being,” of great power, and even with a will of its own. Thus, it is believed that every time someone takes the brew she has the opportunity of entering into direct contact with God and, if she is deserving, she might then be able to find solutions for problems she may be facing and even be healed of terminal illnesses, as many followers claim to have been.

Many aspects of the Daimista ritual setting promote order, such as:

- The dietary and behavioral prescriptions that must be observed during the three days that precede and that follow the taking of the drink, setting the stage for an unusual event that escapes the daily routine.

- A hierarchical social organization in which a “commander” or “godfather” is recognized as the leader of the session, with the help of a body of “guardians” who are responsible for the maintenance of order and obedience to the commander.

- The control of the dosage of the drink taken by participants.

- The ritualized spatial organization, the uniforms generally worn, and the behavioral control of the participants.

All “works” take place around a central table/altar where the double-armed Cross of Caravacca and other religious symbols mark the sacred nature of the event. All those taking part are given a specific place in the room, usually a rectangle drawn on the ground, where they must remain, grouped by sex, age, and sexual status (virgins and non-virgins).

Regular members must usually wear uniforms of a sober cut that serve to stress the unity of the group and help maintain a mood of seriousness. Another important element of control is the music which is sung and played during most of the ceremonies, and which is of great help in harmonizing the group, with rattles marking the rhythms and the voices of the congregation in unison. This ritual use of music harkens back to ancient shamanic customs. Singing and the use of percussion instruments with a strong, repetitive beat are powerful aids in bringing about altered states of consciousness and are thought to act as a way of invoking spirits. The words of the “hymns” direct the “voyages” of the participants and help relieve mental or physical ill-feelings.

The hymns also help to create connections between the lived experiences and the magical or mythical symbols with which they become invested, and which are of great importance in strengthening the cohesion of the group.

In 1986, the spreading of this and other ayahuasca religions among the middle classes of the large Brazilian cities outside the Amazon region, the publicity involving the conversion of media celebrities to the Santo Daime, and the moral panic over drug use, led the Brazilian Ministry of Health to place the brew in the list of forbidden drugs.

In response, one of the ayahuasca-using religions, the União do Vegetal, petitioned the Federal Narcotics Council to annul the measure. The Council decided to set up two multidisciplinary work groups to report on the matter. These groups included not only lawyers and policemen but also doctors, social scientists, and psychologists. Over a period of two years, they visited several of the religious communities, examined and interviewed their followers, and read news reports.

In their unusually enlightened final reports, the work groups noted that ayahuasca had been used by these religious groups for decades without any untoward social harm. Among the users of the brew the predominant moral and ethical standards were seen to be similar to those found in mainstream Brazilian society. The rural communities were considered to be well integrated in their environmental settings and as harmoniously integrating individuals of different age groups, social classes, and social backgrounds. In spite of their distance from the Amazon even the urban communities were found to follow closely the doctrinal practices originating in the rainforest. Although the brew was classified as a hallucinogen and as having other effects apart from those common to this type of substance, such as vomiting and diarrhea, no medical abnormalities were detected and recommendations were made for further and more detailed clinical studies. Following the work group’s recommendations, the use of ayahuasca for religious purposes was then endorsed by the Federal Narcotics Council and since then has been considered totally legitimate from a legal point of view, although the religions are still occasionally subject to social prejudice on the part of those who continue to consider adherents to be mere drug addicts.

Join us for our next conference!

Keeping within the Santo Daime universe, it is useful to compare the fortunes of the legally accepted ayahuasca with another sacramental substance also worshipped by the followers of one of its branches but which remains illegal: “Santa Maria” or Cannabis.

For the members of Colônia 5000 in the mid-1970s, the smoking of marijuana was not an issue, although a few had heard tales about its supposed diabolical nature and its use by outlaws. Their main concern was with alcoholism, endemic in the region and a personal problem for many of the veterans, who considered the Santo Daime to be responsible for their having given up excessive drinking. Tobacco smoking, though discouraged during rituals, was a socially accepted practice and quite widespread.

On the other hand, many of the new young converts had originally been attracted to the religion because of its uses of a psychoactive brew as its main sacrament. Their conversion, although it involved many changes in their value systems, had also led them to view consciousness alteration through substance use not only as socially acceptable, but also as a sure way of acquiring spiritual knowledge and development.

“THEIR CONVERSION… LED THEM TO VIEW CONSCIOUSNESS ALTERATION THROUGH SUBSTANCE USE NOT ONLY AS SOCIALLY ACCEPTABLE, BUT ALSO AS A SURE WAY OF ACQUIRING SPIRITUAL KNOWLEDGE AND DEVELOPMENT.”

Emphasizing its specific character, this new religious use was to have a different vocabulary from the profane street use so that, like Santo Daime, Santa Maria should never be considered a “drug.” Not only was the name commonly used in Brazil, maconha, rejected and substituted with “Santa Maria,” but all the other terms used in connection with it, like the standard urban Portuguese word for “to smoke,” or hippie slang expressions for cigarette papers and the top of the female plant—very prized for being rich in THC—were substituted by other expressions of a more local flavor. Of special significance was the name adopted for those who partook of this sacrament. Leaving aside the Portuguese term maconheiro (roughly equivalent to “pot head”), which had strong deviant connotations, the religious users of Santa Maria became known as marianos, an expression used in the Roman Catholic Church for the members of certain brotherhoods devoted to the cult of the Virgin Mary.

Dealing with rituals, which are not only social but religious as well, we see how they can be quite effective when allowed to develop in a licit manner, even when dealing with potent substances like ayahuasca. On the other hand, when rituals are banned it makes it difficult for them to become fully institutionalized, as is the case with Santa Maria, their controlling influence is weakened and it is more difficult to prevent undesired effects. Fortunately, in the case of the Daimista “marianos” or “devotees of the Virgin Mary,” adherence to the doctrine provides them with a structure for their lives.

This article was translated by John Milton from: MacRae, Edward, 2005, “Santo Daime e Santa Maria: usos religiosos de substâncias psicoativas lícitas e ilícitas” In Labate, Beatriz and Sandra Goulart, O Uso Ritual das Plantas de Poder, Campinas: Mercado de Letras. Pp. 459-485.

Art by Trey Brasher.

References

Adiala, J.C. 1986a A Criminalização dos Entorpecentes. In Seminário “Crime e Castigo.” Rio de Janeiro: Fundação Rui Barbosa

Adiala, J.C. 1986b O Problema da Maconha no Brasil- Ensaio Sobre Racismo e Drogas. Série Estudos, N.52, October 1986. Rio de Janeiro: Instituto Universitário de Pesquisas do Rio de Janeiro.

Alverga, A.P. (org.) 1998 O Evangelho Segundo Sebastião Mota. Céu do Mapia: CEFLURIS.

Andrade, A.P. 2002 Contribuições e Limites da União do Vegetal Para a Nova Consciência Religiosa. In O Uso Ritual da Ayahuasca. B. Labate and Sena Araujo, W.Campinas: Mercado de Letras.

Bennett, C., Osbourn, L. and Osbourn, J. 1995 Green Gold the Tree of Life-Marijuana in Magic and Religion. California: Access Unlimited.

Couto, F.R. 1989 Santos e Xamãs. Master’s thesis, Universidade de Brasília, 251 pp.

Emboden Jr., W. A. 1972 Ritual Use of Cannabis Sativa L.- A Historical Ethnographic Survey. In Flesh of the Gods: The Ritual Use of Hallucinogens. P.T.Furst, ed. New York: Praeger.

Escohotado, A. 1989 Historia de las Drogas. Madrid: Alianza Editorial, 3 vols.

Fericgla, J.M.1989 El Sistema Dinâmico de la Cultura y los Diversos Estados de la Mente Humana – Bases para un Irracionalismo Sistêmico. Cuadernos de Antropologia. Barcelona: Editorial Anthropos, 80 pp.

Grund, J.P.C. 1993 Drug Use as a Social Ritual- Functionality, Symbolism and Determinants of Self-Regulation. Rotterdam: Instituut voor Vesslvingsondeerzoek.

Labate, B.C. 2000 A Reinvenção do Uso da Ayahuasca nos Centros Urbanos. Master’s thesis (Social Anthropology), State University of Campinas (UNICAMP).

MacRae, E. 1992 Guiado Pela Lua – Xamanismo e Uso Ritual da Ayahuasca no Culto do Santo Daime. São Paulo: Brasiliense, 195 pp.

Mortimer, L. 2000 Bença Padrinho. São Paulo: Céu de Maria.

Ott, J. 1995 The Age of Entheogens. California: Natural Products.

Ovejero, F.C. 1996 Relatos del Santo Daime. Madrid: AMICA.

Schultes, R.E., Hofmann, A. 1987 Plants of the Gods Origins of Hallucinogenic Use. New York: Alfred Van Der Marck Editions.

Silva, C.M. 1985 Ritual de Tratamento e Cura, 1 Simpósio de Saúde Mental, Sociedade Brasileira de Psiquiatria, Santarém, August 1985.

Wasson, R.G., Hofmann, A. Ruck, C.A.P. 1980 El Camino a Eleusis- Una Solucion al Enigma de los Misterios. Mexico, Fondo de Cultura Económica.

Zinberg, N. 1984 Drug, Set and Setting: The Basis for Controlled Intoxicant Use. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

Discover the Indigenous Reciprocity Initiative of the Americas

Take a minute to browse our stock:

Did you enjoy reading this article?

Please support Chacruna's work by donating to us. We are an independent organization and we offer free education and advocacy for psychedelic plant medicines. We are a team of dedicated volunteers!

Can you help Chacruna advance cultural understanding around these substances?