- Could Synthetic Mescaline Protect Declining Peyote Populations? - August 2, 2021

With populations of peyote rapidly dwindling due to loss of natural habitat and unsustainable harvesting practices, synthetically produced mescaline, along with cultivation of other mescaline rich cacti, offers a more ethical and sustainable solution to meet the increasing demands of the entheogen.

A Brief History of Peyote and Mescaline

While the psychoactive effects of the peyote cactus were apparent to Western consciousness since the Spanish conquest of Mexico in the early sixteenth century, the principal active ingredient, 3,4,5-trimethoxy-β-phenethylamine, otherwise known as “mescaline,” was not identified and isolated until 1897 by German chemist Arthur Heffter.

While the psychoactive effects of the peyote cactus were apparent to Western consciousness since the Spanish conquest of Mexico in the early sixteenth century, the principal active ingredient, 3,4,5-trimethoxy-β-phenethylamine, otherwise known as “mescaline,” was not identified and isolated until 1897 by German chemist Arthur Heffter. Previously, the usage of peyote had been suppressed (albeit unsuccessfully) by Catholic missionaries in the Americas, fueled by beliefs of the cactus facilitating communication with the Devil. However, during the late nineteenth century, Western researchers became increasingly interested in hallucinogenic substances. Heffter’s identification and isolation of mescaline inspired a number of clinical trials in hopes of using the drug to model psychosis and thus elucidate its underpinnings. Then, in 1918, Viennese chemist Ernst Späth pioneered a bespoke synthesis of mescaline from common chemical building blocks and corrected a small but significant error in the molecular structure originally proposed by Heffter. Now that its production was disentangled from the need to obtain large quantities of peyote, clinical research further intensified (Abbott, 2019).

Recordings are now available to watch here

Mescaline became the prototypical psychedelic drug and was used as the benchmark standard by which other entheogenic substances, such as LSD and psilocybin, would be measured. Through a range of well-intentioned clinical studies, and some contrastingly insidious US government-run experiments during the 1940s and 50s, interest in mescaline continued to gather momentum. Dramatically blasting open the doors of perception for Aldous Huxley, the cactus-derived hallucinogen’s popularity dramatically increased after the publication of his seminal work. During the 1960s’ counterculture movement, and ever after, increasing numbers of people have been traveling to South Texas and Mexico with the intention of consuming peyote and experiencing its reputed transcendent effects. Now, the New Age tourists are more likely to travel to Mexico than Texas to obtain peyote, particularly in San Luis Potosi, a sacred site visited over the centuries by Huichol pilgrims (Schaefer, 2017).

The rise in popularity of peyote has unfortunately led to a certain degree of overharvesting using unsustainable methods. Owing to its slow growth rate, the cactus can only be harvested sustainably once every eight years to allow sufficient time for the psychoactive succulent to recover (Ermakova & Terry, 2020). Moreover, the habitat available to peyote has shrunk drastically in the last 60 years. In Texas, native thornscrub has been cleared for agriculture, development, cattle pastures, energy infrastructure; and similarly, in Mexico, mining, agrobusiness, and other development have similar effects. Furthermore, the potential effects of climate change on peyote populations are unknown (Ermakova, 2019). The combination of the aforementioned factors has led to a significant decline in both US and Mexican peyote populations over the last 60 years, to the point that the cactus is now considered a vulnerable species. Overharvesting also leads to reduced sexual reproduction and, in turn, a loss of genetic diversity within populations, thereby posing a significant threat to the continuing survival of this species in the wild (Ermakova, 2020).

Synthetic Mescaline

With the increasing need to protect peyote, synthetic mescaline may offer an alternative gateway into this experience that is free from issues regarding sustainability.

With the increasing need to protect peyote, synthetic mescaline may offer an alternative gateway into this experience that is free from issues regarding sustainability. The consumption of peyote and other mescaline-containing cacti is symbiotically united with their respective ritualistic cultural contexts and, therefore, the totality of the experience cannot be conveniently encapsulated by reductionistic pharmacological descriptions. Each cactus, and the respective experience they produce, represents a unique facet of the cultures of which they are a treasured part. So, while from a scientific standpoint, the physiological and psychological effects of consuming pure mescaline are comparable with that of the whole cactus, be aware that they are not necessarily interchangeable from a cultural standpoint.

A 12–16-hour experience with an empathogenic, organic richness, along with a lucid and clear headspace from which to traverse the infinitude of experiences that can arise from the human psyche, mescaline has the potential to be profoundly transformative and healing on both personal and collective levels.

Discover the Indigenous Reciprocity Initiative of the Americas

Offering a trip notably distinct from that produced by LSD, psilocybin, or DMT, mescaline occupies a unique niche among the classical psychedelics, making it a much sought-after experience. A 12–16-hour experience with an empathogenic, organic richness, along with a lucid and clear headspace from which to traverse the infinitude of experiences that can arise from the human psyche, mescaline has the potential to be profoundly transformative and healing on both personal and collective levels.

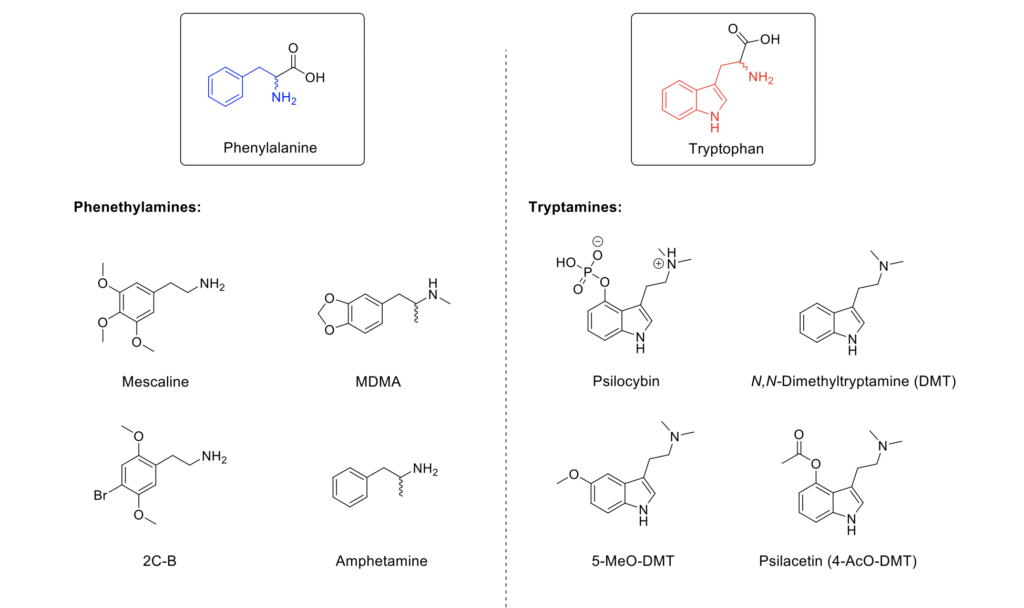

Chemically, mescaline is part of a family of psychoactive compounds known as the phenethylamines: compounds derived from the structure of the amino acid phenylalanine. MDMA, amphetamine, and 2C-B are other notable compounds belonging to this chemical class. While they share a common mechanism of action—acting as high-affinity agonists for the 5-HT2A receptor in the brain—mescaline is chemically distinct from the tryptamine class of psychedelics (psilocybin, DMT, 5-MeO-DMT, etc.), which are instead derived from the structure of the amino acid tryptophan.

The Synthesis of Mescaline

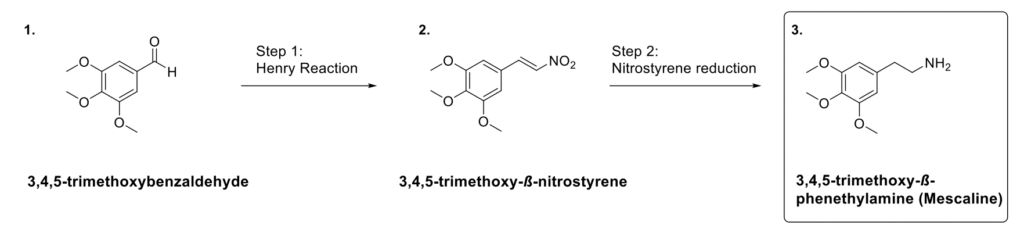

Ernst Späth’s original synthesis begins with gallic acid (3,4,5-trihydroxybenzoic acid) and comprises five chemical transformations to obtain mescaline as the final product (Soukup, 2019). With modern chemical supply houses stocking a much broader array of chemical building blocks than in Späth’s era, one of the intermediates, 3,4,5-trimethoxybenzaldehyde, is cheaply and readily available. The ease of availability of this chemical building block renders the synthesis of mescaline a mere two steps, which was documented by pioneering psychedelic chemist Alexander Shulgin in the classic work PIKHAL: Phenethylamines I Have Known and Loved (Shulgin & Shulgin, 1995). Based on the yields reported in the literature from this synthetic route, one could expect 100 grams ($55.00 worth) of 3,4,5-trimethoxybenzaldehyde to produce approximately 87 grams of pure mescaline. With a common dosage being 300 mg, that is 290 doses. To put that into context, one would need to acquire approximately 22 kilograms of fresh peyote or 1300 peyote buttons to extract an equivalent quantity (Gupta, 2018). It is also worth noting that, with modern scale-up chemistry technology and innovation, this yield could likely be increased, along with a significant reduction in the time needed to synthesize a batch.

With the need to protect peyote becoming increasingly paramount, the legalization of mescaline would help facilitate this through reducing the demand for poached peyote.

With mescaline being a Schedule I substance, only labs with an appropriate license can produce it in restricted quantities for use in clinical studies. With the need to protect peyote becoming increasingly paramount, the legalization of mescaline would help facilitate this through reducing the demand for poached peyote. Ironically, in the past, the very scheduling of mescaline and refusal to allow its legal regulation encouraged the harvesting of peyote as a means to experience mescaline. Proper legislation could therefore allow for the existing demand to be met increasingly with synthetically-produced mescaline and thereby reduce peyote harvesting from the wild.

Please donate to the Psychedelic Renaissance Documentary

Extracted Mescaline and the Echinopsis Cacti

Notorious occultist Aleister Crowley was thought to have indulged in the use of an “extra-strength peyote extract” procured by renowned Detroit pharmacists, Parke-Davis (now a subsidiary of pharma giant Pfizer) to assist with his visionary work

Regarding the audacious tendency of pharmacologists to dose themselves with novel, extracted psychedelic alkaloids in the name of… science, mescaline is the original trend-setter. Its activity was discovered when Arthur Heffter set about consuming the various compounds he had painstakingly extracted from peyote to ascertain which were responsible for producing the remarkable visionary experiences it was famous for. Extracts provided a more convenient and easier-to-dose method of consuming mescaline, with the potential for less gastrointestinal discomfort from not having to ingest an entire cactus. This enhanced accessibility encouraged more people outside of the psychiatric professions to experiment with the drug. Notorious occultist Aleister Crowley was thought to have indulged in the use of an “extra-strength peyote extract” procured by renowned Detroit pharmacists, Parke-Davis (now a subsidiary of pharma giant Pfizer) to assist with his visionary work (Partridge, 2017).

In an article exploring the ethics and viability of alternative mescaline sources, it is only appropriate to include a well-rounded discussion of all possible options. Thus, this piece would not be complete without delving into the more sustainable sources of naturally derived mescaline: the Echinopsis family of cacti. Hardy, fast-growing, and rich in mescaline, these columnar cacti are naturally abundant throughout the high-altitude Andean deserts of South America where they are used ritualistically for both healing and divinatory purposes by a variety of different ethnic groups native to the region, such as the Saraguro of the Kichwa nation in Ecuador and mestizo shamans. They can be cultivated with relative ease in a host of other climates and are still legal to possess in many countries.

Qualitatively, the trip produced by consuming whole cactus or a full spectrum extract is subjectively different from the experience of taking pure mescaline

Qualitatively, the trip produced by consuming whole cactus or a full spectrum extract is subjectively different from the experience of taking pure mescaline (Turner, 1994). The cactus/full spectrum extract experience is subject to the “entourage effect,” whereby the other active alkaloids present in the plant produce a synergistic effect with the mescaline, giving rise to a phenomenologically distinct experience. This is akin to cannabis; while the active ingredient is Δ-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), the numerous terpenes and other phytocannabinoids present in the flowers combine to give the experience of smoking whole bud a different quality compared to mostly THC-containing concentrates, e.g., shatter. This contrast is less pronounced with regard to mescaline and cacti, but is still described as significant by many who have tried both. Pure mescaline tends to produce a more lucid, mentally stimulating, and clear-headed experience with stronger visual geometry present relative to the degree of physical effects. Comparatively, whole cactus tends to produce a more earthy, grounded, physically euphoric, body-oriented experience with a higher likelihood of nausea and gastrointestinal discomfort. Each cactus has its own individual effect profile and subjective feel due to differing alkaloid profiles between species.

Depending on the extraction process used and the degree of purification it entails, extracts can contain the full range of active alkaloids present, and therefore resemble a whole cactus experience, or they may be increasingly refined to eventually consist of pure mescaline. To help understand and clarify these different flavors of cactus/mescaline experience, I have put together a summary of each cactus and its respective alkaloid blend, along with the subjective differences in effects below:

San Pedro (Echinopsis pachanoi)

Grows natively in Argentina, Bolivia, Colombia, Chile, Ecuador, and Peru. 6–8 ribs, can grow on average half a meter per year.

Alkaloids: Mescaline (average ~1% dry weight), 3,4-dimethoxyphenethylamine, 3-methoxytyramine, 4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenethylamine, 4-hydroxy-3,5,-dimethoxyphenethylamine, anhalonidine, anhalidine, hordenine and tyramine (Crosby & McLaughlin, 1973).

Effects: Reported to give a smoother, dreamier, more down-to-earth experience than pure mescaline that’s less cerebrally stimulating with a more pronounced euphoric body high.

Peruvian torch (Echinopsis peruviana)

Unsurprisingly, native to Peru, 6–9 ribs, fast-growing like San Pedro.

Alkaloids: Mescaline (up to 0.82% dry weight), 3-methoxytyramine, 3,5-dimethoxy-4-hydroxyphenethylamine, tyramine (Pardanani, et al., 1977).

Effects: Has the highest ratio of mescaline to other alkaloids of all species, and a smaller number of other alkaloids compared to the rest of the Echinopsis family and peyote; the experience is the most similar to pure mescaline.

Bolivian torch (Echinopsis lageniformis)

Native to… you guessed it: Bolivia; thinner and even faster growing than San Pedro or Peruvian torch.

Alkaloids: Mescaline (average 0.56% dry weight), 3-methoxytyramine, 3,4-dimethoxyphenethylamine, Tyramine, Bridgesigenin A, Bridgesigenin B, Kaempferol flavonoid, Quercetin flavonoid (De Sjamaan Internet Sales, 2021).

Effects: The most potent and long-lasting experience of the three Echinopsis cacti. Kaempferol and Quercetin potentially act as monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs), slowing the breakdown of mescaline and other active alkaloids. It is possible the MAOIs impart their own flavor onto the experience also. Described as intense and visionary, compared to the San Pedro and Peruvian Torch, it is more akin to a peyote experience than a pure mescaline trip, although still presenting its own unique, signature quality.

[NB: Experiences with psychedelics can vary hugely from person to person and setting to setting. These descriptions are the summary of anecdotal reports and are meant as guidelines, not objective conjecture about how the experience will play out!]

Extracting Mescaline

The extraction process is typically carried out by stewing, mashed, or powdered cactus cuttings in either an acidic or alkali solution. The initial stew is filtered to remove the cactus debris and made alkaline, if not already, so the active alkaloids are then able to be extracted into a non-polar organic solvent such as toluene or xylene. The organic solvent extracts are combined and then acidified, either with sulfuric or hydrochloric acid, and left to allow the mescaline to precipitate out. This will give a relatively pure extract mostly comprised of mescaline with minor amounts of other alkaloids. It can be further purified at this point to give pure, sparkling white mescaline. If a full spectrum extract is desired the cactus can simply be simmered in 70% alcohol, filtered and the alcoholic extract concentrated. This will yield a tar-like substance that contains the total blend of alkaloids present in the cactus.

(Left): Full spectrum extract of San Pedro with waxy amber appearance. (Right): White purified mescaline from San Pedro cactus extraction. Credit: TheTraveller/Kash.

Final Thoughts

As for illegal access, most of peyote grows on private land, and finding it requires trespassing and also inside knowledge on where to find it. This, coupled with the extremely slow growth rate of the cactus, makes for a rather inconvenient and uneconomical source of mescaline under the current laws.

There has been some concern among opponents to the de-criminalization of psychedelics that the origins of batches of refined mescaline can be hard to ascertain. The fear is of mescaline being illicitly derived from peyote and, therefore, that increasing use of mescaline could contribute to the cacti’s endangerment. Given the significance of peyote to the Native American tribes, this would certainly be a harmful development, potentially damaging their access to this sacrament for many years at a time. However, when looked at through a logistical lens, this reasoning does not hold up very well under scrutiny. The current legislation in the US and Texas, in particular, around peyote harvesting means legal access for those who are not members of Native American Church ranges from extremely limited to virtually non-existent. As for illegal access, most of peyote grows on private land, and finding it requires trespassing and also inside knowledge on where to find it. This, coupled with the extremely slow growth rate of the cactus, makes for a rather inconvenient and uneconomical source of mescaline under the current laws. The extraction process is more suited to the procurement of small-sized batches for personal use, given the sheer quantity of cactus necessary to produce upwards of 5 grams of mescaline. If you follow this logic through to its natural conclusion, and, given that peyote is considered rather desirable to consume whole, the majority of refined mescaline that is available is likely either illicitly-produced synthetic mescaline or originates from small scale extractions of Echinopsis cacti species, which are perfectly legal and fairly easy to grow in the USA. It is highly unlikely to have been derived from peyote at this point in history.

The current “psychedelic renaissance” we are fortunate enough to be living in has been marked particularly by the recognition of plant medicines as allies for the healing of mind, body, and spirit. Given this emphasis, I would like to address a potential assumption that may have arisen implicitly throughout existing cultural presuppositions regarding bioactive compounds and the public discourse surrounding this movement: that synthetic psychedelics do not possess the same depth or capacity for personal insight and healing. The psychedelic experience arises as a result of the meeting of mind, substance, and situation. While that might sound trite, it makes the case that, ultimately, set and setting are most important for determining the trajectory and transformative power of an experience. The substance consumed is but one part of the setting. Although not a direct equivalent to a peyote experience, synthetic mescaline is of potentially equal value and can certainly catalyze deeply profound and meaningful experiences for those who approach its use with the appropriate intentions and respect for the experience.

Art by Mariom Luna.

References

Abbott, A. (2019, May 20). Altered minds: Mescaline’s complicated history. Nature, 569, 485–486. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-019-01571-2. https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-019-01571-2.

Crosby, D. M., & McLaughlin, J. L. (1973). Cactus alkaloids. XIX. Crystallization of mescaline HCl and 3-Methoxytyramine HCl from Trichocereus pachanoi. Lloydia, 36(4), 416–418.

De Sjamaan Internet Sales. (2021), Trichocereus Bridgesii cutting 500–-1000g. https://sjamaan.com/en/trichocereus-bridgesii-cutting.html

Ermakova, A. (2019, October 15). Peyote harvesting guidelines. Chacruna. https://chacruna.net/peyote-harvesting-guidelines/.

Ermakova, A., & Terry, M. K. (2020, May 12). Aword in edgewise about the sustainability of peyote.Chacruna. https://chacruna.net/a-word-in-edgewise-about-the-sustainability-of-peyote.

Ermakova, A., Whiting, C. V., Trout, K., Clubbe, C., Terry, M. K., & Fowler, N. (2020). Densities, plant sizes, and spatial distributions of six wild populations of lophophora williamsii (cactaceae) in Texas, U.S.A. bioRxiv 2020.04.03.023515; https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.03.023515

Gupta, P. K. (2018). Drugs of use, dependence, and abuse. In P. K. Gupta (Ed.), Illustrated toxicology (pp. 331–356). Cambridge, MA: Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-12-813213-5.00012-2

Pardanani, J. H., McLaughlin, J. L., Kondrat, R. W., & Cooks, R. G. (1977). Cactus alkaloids. XXXVI. Mescaline and related compounds from Trichocereus peruvianus. Lloydia, 40(6), 585–590.

Partridge, C. (2017). Aleister Crowley on drugs. International Journal for the Study of New Religions, 7(2), 125–151. https://doi.org/10.1558/ijsnr.v7i2.31941 Available at: https://eprints.lancs.ac.uk/id/eprint/84818/1/Crowley_on_Drugs.pdf.

Schaefer, S. B. (2017, April 18). Peyote: Plant medicine for the body, mind and soul. Chacruna. https://chacruna.net/peyote-plant-medicine-body-mind-soul/#fn-1743-19

Shulgin, A., & Shulgin, A. (1995, May 22). PIHKAL: Phenethylamines I have known and loved: A chemical love story [published online as PIHKAL #96 M]. Berkeley, CA: Transform Press. https://erowid.org/library/books_online/pihkal/pihkal096.shtml.

Soukup, R. W. (2019). On the occasion of the 100th anniversary: Ernst Späth and his mescaline synthesis of 1919. Monatsh Chem, 150(5), 949–956. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00706-019-02415-5

Turner, D. M. (1994). The essential psychedelic guide. San Francisco, CA: Panther Press.

Take a minute to browse our stock:

Did you enjoy reading this article?

Please support Chacruna's work by donating to us. We are an independent organization and we offer free education and advocacy for psychedelic plant medicines. We are a team of dedicated volunteers!

Can you help Chacruna advance cultural understanding around these substances?