- Rethinking Power, Plants, and the Future of Psychedelic Culture - May 9, 2025

- Where Is the Psychedelic Movement Headed Next? - October 15, 2024

- The FDA’s Rejection on MDMA-Assisted Therapy: What is Next for the Psychedelic Movement? - August 16, 2024

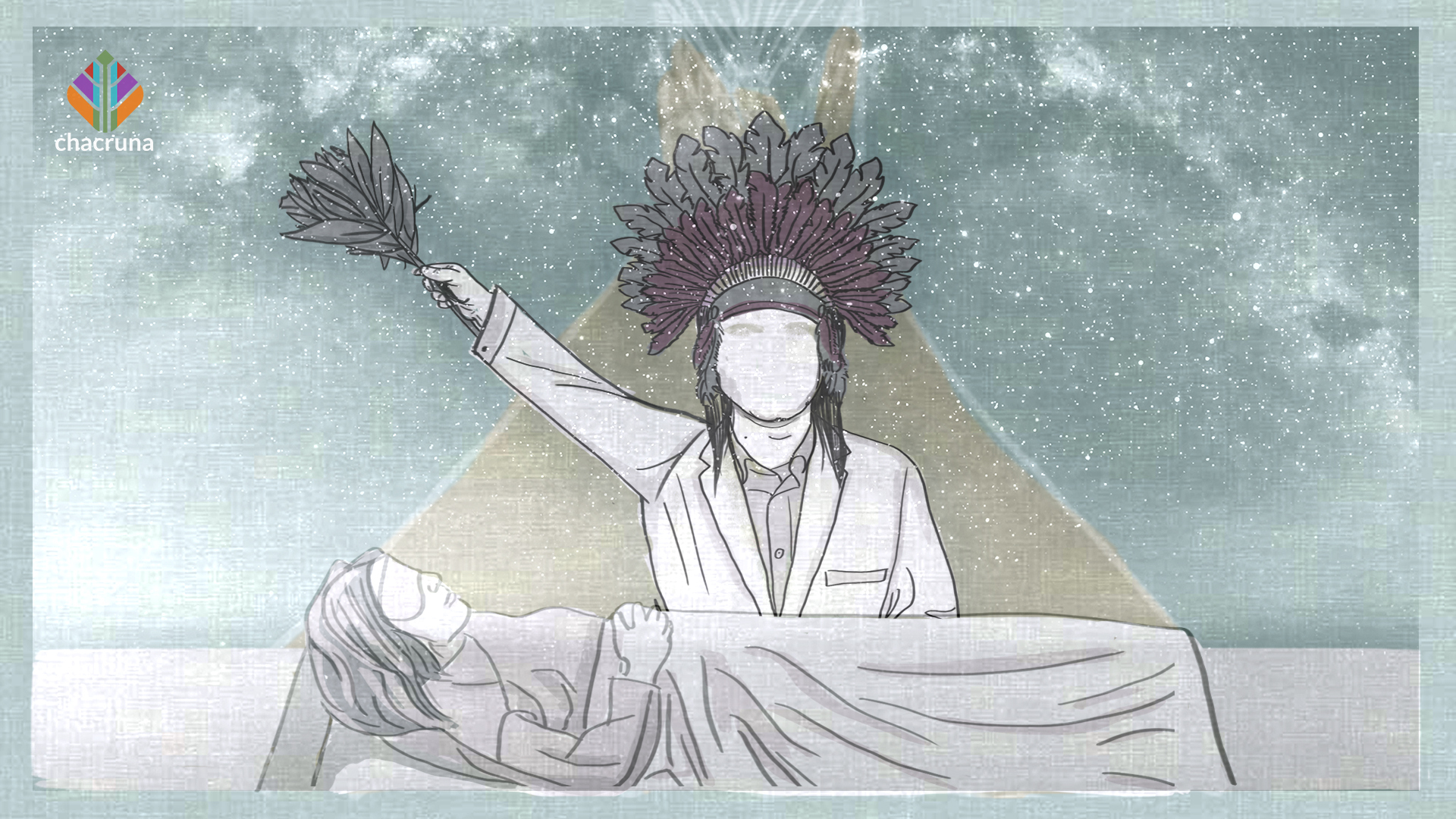

During the Sacred Solidarity Festival, an anthropologist advocates for the need to pay attention to the continuities between the ceremonial use of sacred plants and psychedelic science.

María Sabina famously claimed that psilocybin pills “had the same power as the mushrooms; that there was no difference.” What, in your view, is gained and lost when using synthetic or purified forms of psychedelic compounds versus whole plants or mushrooms?

This claim of Maria Sabina must be relativized. When I saw Jonathan Ott in Basel years ago, reflecting on this story, he said, “probably she was just trying to be nice, e.g., if you bring a cake to the house of an old and humble lady and ask her if she likes it, she will consider that it is your gift to her and will approve it.” Maria Sabina’s phrase has been used to legitimize the use of synthetic substances in research, but this single alleged claim does not solve the problem and complexity of these issues!

Let me make it clear that I am a plant person, not a synthetic person. I really like ayahuasca, mushrooms, and peyote much more than MDMA or LSD. But I think we must distinguish between personal preferences and political claims. For example, a person can be straight, but think that gay people should also have rights. One thing is what you prefer personally, and the other is what you think we should do intellectually and politically about these issues.

So, what are the political implications and distinctions that are important here?

At the Chacruna Institute for Psychedelic Plant Medicines, we are trying to create bridges between the ceremonial and traditional use of sacred plants and psychedelic science, as well as to promote inclusion and diversity in the field

I think it is good to build bridges between the world of synthetics and non-synthetics. At the Chacruna Institute for Psychedelic Plant Medicines, we are trying to create bridges between the ceremonial and traditional use of sacred plants and psychedelic science, as well as to promote inclusion and diversity in the field. So, in other words, we would like to see Indigenous knowledge and practices more incorporated into the field of psychedelic science. That includes the appreciation for plants as a whole, and also for ceremony and tradition. At the same time, these “bridges” should be multidirectional: What is there for Indigenous people in participating in our publications and events? They should not be included just to justify our need for representation, or white folks’ guilt.

What does this mean to claim to that psychedelic scientists should create bridges with Indigenous ceremonial uses and traditions? It does not mean that we should abandon science or deny it. We should question the privileged position of science, take Indigenous knowledge equally seriously, and stop considering it “symbolic” or “subjective” versus the “objective” and “factual” science. As Evgenia Fotiou pointed out in an article for our special issue, Diversity, Equity, and Access in Psychedelic Medicine, “as feminist scholars have pointed out, all knowledge is ‘situated’ – stemming from a certain objectivity and viewpoint and is intimately connected to power structures.”

So, coming back to the dichotomy of synthetic and purified forms versus whole plants.

LSD is not Indigenous, although its creation was inspired by the observation of the active substance ergotamine from ergot, a fungus found in tainted rye that had been used as a folk medicine for generations. MDMA was invented in Germany in 1912 to control bleeding. MDMA is a “mescaline-like compound,” which means that mescaline’s molecular structure is present in MDMA. And mescaline’s molecular structure was identified by studying peyote, the main sacrament of Native Americans, besides tobacco. Even if the origins of LSD or MDMA are not directly Indigenous, and even if they were not originally invented as psychedelic drugs, they activate the same serotoninergic receptors that traditional Indigenous sacraments do.

The very origin of the term “psychedelics” has a legacy from these scientists’ experiences with Native Americans and curiosity about the rituals that accompanied their use.

Join us at Sacred Plants in the Americas II

More importantly, I would like to remark that some of the original scientists promoting “psychedelic science” emerged in the context of researchers sitting in tipis with Native Americans in Canada. Humphry Osmond and Abram Hoffer were starting to experiment with LSD as a treatment for alcoholics. Their experiences with the NAC (Native American Church) group in Canada demonstrated to them that the NAC was effectively treating alcoholism and they found many parallels (Erika Dyck, personal communication, 2020). The very origin of the term “psychedelics” has a legacy from these scientists’ experiences with Native Americans and curiosity about the rituals that accompanied their use.

So, wouldn’t it be good if we could rescue a bit more of the spiritual, ceremonial, and traditional dimensions of the idea of “psychedelics?”

And, as both synthetics and plants go mainstream, wouldn’t it be nice to be reciprocal to Indigenous populations and inclusive of them? Shouldn’t we recognize that Indigenous knowledge keepers have, in one way or another, informed the psychedelic movement, and continue to do so?

Albert Hofmann suggested that healing humanity’s relationship with the natural world would require “existential experience of a deeper, self-encompassing reality,” and that, without this, efforts to protect the environment would be “hopeless, superficial patchwork.” Was Albert right?

One could say that, in this passage, Albert is touching on some aspects of Indigenous understanding around healing; that is, it’s not only about the self, it’s about the collective.

Indigenous people have much to teach us about the arts of healing, and also about our relationship to nature. Indigenous understanding frames disease in different ways, and healing is not focused on the idea that there are substances with a psychoactive principle that can heal us; healing is part of a larger holistic perspective that includes relationships between people and between people and nature and the cosmos. Diseases are considered to be the result of imbalance with the natural world and others, or a punishment for failed reciprocity with the cosmo-ecological environment.

The idea that a specific treatment should be applied to a specific disease is prevalent in Western biomedicine; however, from the perspective of other ethnomedical systems, healing is a more holistic enterprise.

If our clinical approaches truly dialogue and collaborate with Native practices, revolutionary creative possibilities might arise.

We can’t just reproduce, appropriate, or imitate a set of techniques that come from Indigenous peoples. We should be able to both decolonize healing and also reconcile our relationship with Indigenous people. If our clinical approaches truly dialogue and collaborate with Native practices, revolutionary creative possibilities might arise.

How have psychedelics altered your relationship and attitudes towards nature and the more-than-human world? Is there more that the psychedelic community could do to engage with the current ecological crisis?

According to Amerindian thought, plants are also humans. Coming from the world of ayahuasca, there is the idea of a “plant teacher.” Plants are also alive, have agency, intentionality, and their own personality. If you obey certain rules, they can teach you and comfort you, or, if not, punish you.

According to Amazonian cosmologies, humans, animals, and plants are all people, and there is some kind of equivalence between humans and non-humans; we all share the biosphere and participate in a wider community of living beings.

Anthropologists and Indigenous leaders have been writing about how the current coronavirus pandemic might be the result of our transgressions against Nature.

Only with the understanding that nature is not alien to us, and that we all share a common humanity, can we start envisioning ways out of the current ecological crisis.

So, yes, traditional Indigenous wisdom can teach us how to revisit our Western dichotomies of “nature and culture,” “mind and body,” “animate and inanimate,” and so forth. Only with the understanding that nature is not alien to us, and that we all share a common humanity, can we start envisioning ways out of the current ecological crisis.

Yesterday, for other reasons, I was interviewing Troy, who is Comanche, but I took advantage of the opportunity to ask him something, as I was trying to come up with something intelligent to say today. Troy leads the Sia project. As the only tribal feather repository in the United States, Sia gives access to all 574 Tribal Nations to legal feathers for ceremonial use to support their cultural sovereignty. Through artificial insemination, they have bred more eagles released to the wild than anyone in history. So, I asked him what he thinks Indigenous people could teach the psychedelic movement, and this is what he replied:

“You have to learn how to honor. Imagine if you see a bird flying, and you consider the universe is honoring you with that gesture. Wouldn’t that change things?”

This is sweet and simple, no?

Art by Mariom Luna.

—

Note: This presentation was given at the panel: “An intersectional dialogue on the history of psychedelics and plant/fungal medicine and how our relationship with nature can heal us.” Sacred Solidarity Online Festival. Spore, April 19, 2020. https://www.thespore.org/sacred-solidarity-festival

Take a minute to browse our stock:

Did you enjoy reading this article?

Please support Chacruna's work by donating to us. We are an independent organization and we offer free education and advocacy for psychedelic plant medicines. We are a team of dedicated volunteers!

Can you help Chacruna advance cultural understanding around these substances?