- After 2024, the Scenario for Psychedelic Therapies Can Only Improve - January 16, 2025

- Symposium in Brazil Debates Psychedelics at a Political Crossroads - December 13, 2024

- Conference in Rio Defends Psychedelics in Public Health - December 11, 2024

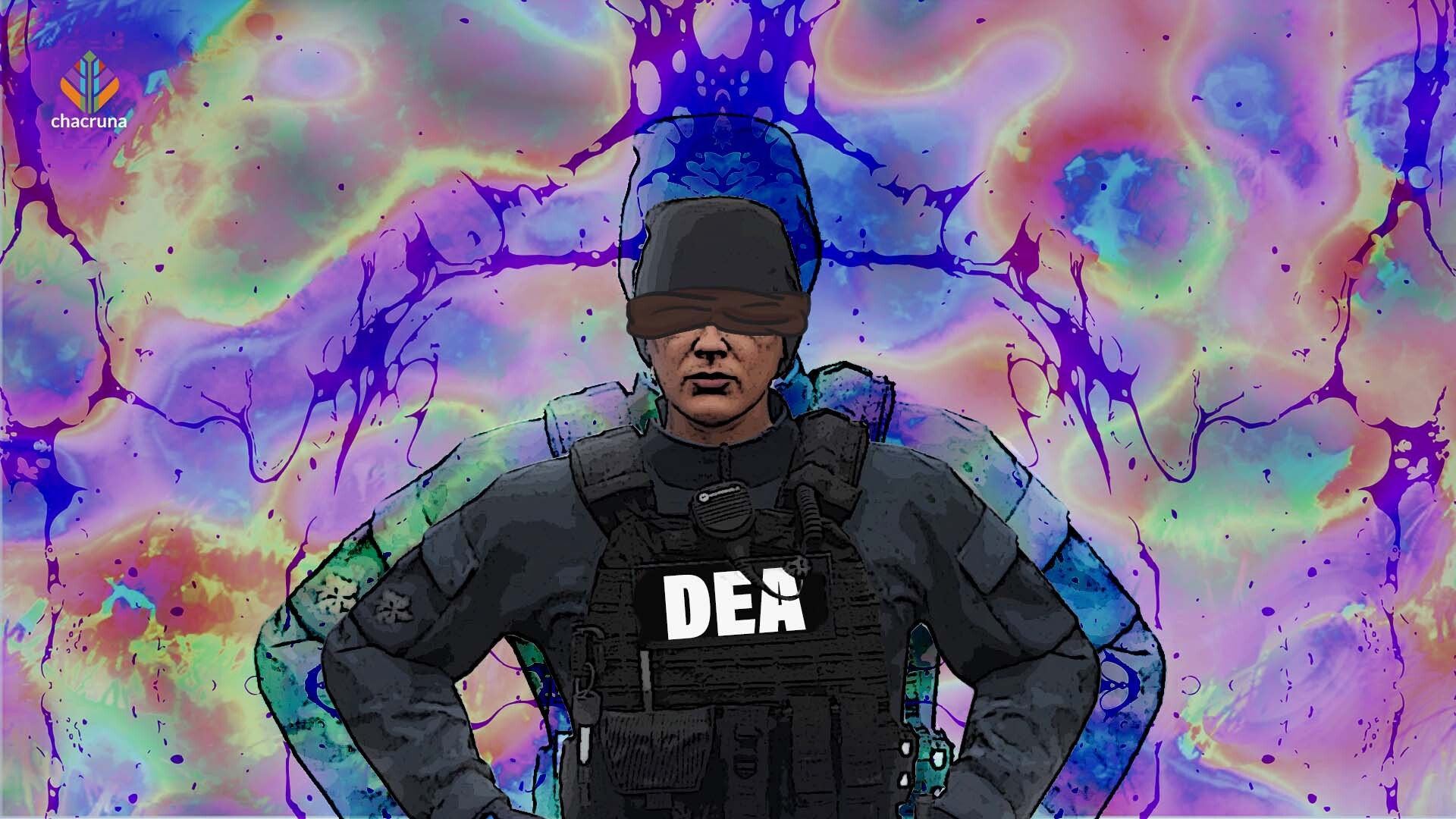

The Drug Enforcement Agency Overestimates Risks and Underestimates Ayahuasca’s Therapeutic Potential

To give a text the appearance of reliable knowledge, based on scientific evidence, is a powerful rhetorical device, even more so when a government agency produces an internal document to justify a retrograde public policy. It is no different when it comes to the U.S. drug enforcement agency’s approach, as seen in the DEA’s report on ayahuasca made public by San Francisco’s Chacruna Institute on Friday.

The 33-page document was obtained by the NGO based on the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA). It is entitled “Ayahuasca: Risks to Public Health and Safety.” It dates back to July 2020, but its existence only became known in April 2021 through a DEA letter to Chacruna and the Church of the Eagle and the Condor (CEC), co-author of the access to information request.

In the US, ayahuasca religions such as the União do Vegetal (UDV) had their right to consecrate ayahuasca recognized by the Supreme Court in 2006, based on the constitutional principle of religious freedom. The CEC, however, faces hurdles to dispensing the sacrament, as the biases of the DEA report on the health and safety of the beverage contribute to upholding stigmas.

As soon as they learned of the report’s existence, Chacruna and CEC included it in their FOIA request. They had to wait almost two years to get access to the document. This happened in a country that boasts itself as a beacon for democracy and the rule of law.

Chacruna’s webpage on which a facsimile of the report is presented states that “The language of [DEA’s] assessment fails to take into account the benefits of ayahuasca and likely overestimates the risks of ayahuasca use, particularly in a controlled, religious or spiritual context, with adequate screening and informed consent procedures.”

“The language of [DEA’s] assessment fails to take into account the benefits of ayahuasca and likely overestimates the risks of ayahuasca use, particularly in a controlled, religious or spiritual context, with adequate screening and informed consent procedures.“

Chacruna Institute for Psychedelic Plant Medicines

The tone of the DEA’s report is alarmist, as it reads on page 10: “[…] despite claims that ayahuasca is safe, the use of ayahuasca has been associated with moderate cardiotoxicity, neurotoxicity, psychopathology, transient disorientation, anxiety, coma, and death.”

Many of the highlighted risks were based on studies with dimethyltryptamine (DMT), which is just one of the psychoactive compounds present in ayahuasca. Although it is generally identified as the trigger for the visions (“mirações,” in Portuguese) that the beverage engenders, DMT acts in association with a complex mixture of substances from the plants—chacruna and the mariri vine—used in its preparation.

On the same page, the report says that the American Association of Poison Control Centers (AAPCC) registered 538 cases of ayahuasca-related emergencies between 2005 and 2015. Among these incidents, there were 150 cases of hospitalization in ICU or semi-ICU, with 28 people intubated, 7 respiratory arrests, and 4 cardiac arrests. One must stress that this happened over a ten-year period.

On page 11, it is reported that data requested by the DEA from the AAPCC for the 2012-2017 period indicated 341 health-related cases regarding ayahuasca and 122 regarding DMT. Regarding ayahuasca, the episodes involved cardiotoxicity (tachycardia and hypertension); 6 respiratory arrests and 3 cardiac arrests; 33 intubations or ventilations. The DEA itself points out that 43% of the cases involved the use of ayahuasca together with one or more substances. Hence, there is no possible way to attribute the serious adverse effects directly to ayahuasca.

On page 13, the report highlights the clinical case of a 36-year-old man with a history of psychosis associated with marijuana abuse. On page 14, the document addresses media reports: 9 cases of deaths during or after rituals. But, again, the DEA recognizes that the available evidence does not allow it to state that the deaths are directly linked to ayahuasca.

These caveats give the DEA’s document an appearance of scientific impartiality. On page 15, however, the negative bias against ayahuasca becomes explicit: despite citing studies saying that one would need to multiply 15 to 50 times the amount of ayahuasca ingested in rituals to reach the lethal dose, the DEA resorts to the allegation that the method of preparation varies widely in order to claim that there is still a considerable risk: “therefore, the use of ayahuasca in a religious ceremony or for recreational purposes could result in amounts of DMT that approach the LD50 dose and, consequently, may lead to DMT intoxications and/or extreme psychoactive effects.” (LD50 is a standardized measure for the amount of any chemical compound capable of causing the death of 50% of the rodents employed in toxicological tests).

On pages 17-18, after citing pharmacological literature showing that DMT does not induce tolerance, which would require subsequent ever-increasing doses, the DEA resorts again to a hypothetical possibility to assert that it is likely to cause chemical dependence: they claim that there is evidence of structural changes in the brain with long-term ayahuasca use, and these changes could lead to addiction.

The strategy of overestimating the risks continues on pages 19-20. The DEA cites only four clinical cases of psychotic breaks after ayahuasca use. Nevertheless, the agency stresses that (p. 19): “Although the occurrence of psychosis from ayahuasca is low, the consequences or health outcomes of developing psychosis can be severe.”

On page 20, when dealing with mortality reported in the medical literature, the report begins by mentioning a single death of a young man who had taken a high dose of 5-MeO-DMT in a drink he thought was ayahuasca, although that amount could not have come from natural sources, only from a synthetic compound… (5-MeO-DMT is a compound related to dimethyltryptamine found naturally in the venom of some frogs.)

Discover the Indigenous Reciprocity Initiative of the Americas

When addressing the potential health benefits, the DEA reverses the pattern: they claim that the research available is very limited, with fragile conclusions compromised by several factors. That is, any beneficial effects could, in theory, be attributed to other circumstances of the psychedelic ayahuasca experience, such as the feeling of welcome in a religious ceremony with chanting.

There is, however, a serious omission from the biomedical literature in the bibliography used by the DEA experts: although the document dates back to July 2020, it did not include the first placebo-controlled clinical trial of a psychedelic substance (ayahuasca, in this case) to treat depression. The research, which included 29 volunteers, was conducted by Dráulio de Araújo’s group at the Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte-UFRN (Palhano-Fontes et al., 2019).

With so many biases, it is not surprising that the DEA’s conclusions are not encouraging when it comes to the ceremonial beverage: “Although ayahuasca has been alleged to have beneficial psychological effects, there are not enough well-controlled studies to support this claim. More well-controlled clinical studies are needed to assess its full therapeutic potential and to increase and diversify the study population.”

The report concludes that: “More studies are also needed to link the positive or negative findings specifically to ayahuasca and not to the context in which ayahuasca was used, and to evaluate the long-term or persistent effects of ayahuasca and its constituents on mental health. Until these studies are completed and the outcomes are analyzed, it cannot be stated that ayahuasca is safe” (p. 24).

It is not surprising that the DEA has been slow to provide access to the report, which seems tailored to bolster the prohibitionist doctrine of law enforcement, even in the face of growing evidence in favor of ayahuasca.

It is not surprising that the DEA has been slow to provide access to the report, which seems tailored to bolster the prohibitionist doctrine of law enforcement, even in the face of growing evidence in favor of ayahuasca. They ignore not only part of the scientific results available, but also the safety of the ritual use of ayahuasca by Indigenous Peoples of the Amazon for centuries, if not millennia, and for almost a century by urban ayahuasca religions in Brazil, such as Santo Daime, Barquinha, and UDV.

Anyone who wants to learn about ayahuasca in a more balanced way will find plenty of information in the academic literature. One of the most recent articles, published in the journal European Neuropsychopharmacology and authored by a group of Brazilian researchers, Lucas Maia, Dimitri Daldegan-Bueno, Isabel Wießner, Dráulio de Araújo, and Luís Fernando Tófoli, is entitled “Therapeutic Potential of Ayahuasca: What We Know and What We Do Not Know.”

According to those experts on depression and psychedelics (ayahuasca and inhaled DMT), the systematic survey of the literature indicates that the evidence for ayahuasca’s therapeutic effect is strongest when it comes to depression and substance abuse (drug addiction).

Another extensive literature survey on the beverage, also called daime, was published just over a year ago by Edward James, Joachim Keppler, Thomas Robertshaw, and Ben Sessa. The survey was published in the journal Human Psychopharmacology, with the title “N, N-dimethyltryptamine and Amazonian Ayahuasca Plant Medicine.”

Sessa is the author of a very interesting introductory book on the subject, The Psychedelic Renaissance – Reassessing the Role of Psychedelic Drugs in 21st Century Psychiatry and Society. It was published by Muswell Hill Press in 2012.

His recent article with James, Keppler, and Robertshaw provides a good example of how a positive bias, or at least a disengagement from the prohibitionist paradigm, can result in a much more generous appreciation of ayahuasca’s potential, as well as a better understanding about its unknown features and effects.

Citing broadly the same literature surveyed by the DEA, they approach the issue in a far more sympathetic manner: “A change of Schedule [removing the substance] from the Schedule I list, acknowledging potential medical applications of DMT is justifiable at this point and such a change in Schedule would facilitate further medical studies.” Schedule I includes the list of banned substances in the US.

At no point do Sessa and his coauthors minimize the risks involved in ingesting ayahuasca, but neither do they lose sight, as the DEA does, that its use is noticeably safe in a community that promotes its consumption in a ritual context. The UDV alone, for example, has 22,000 members that drink the beverage regularly, every other week, with very rare serious adverse effects.

After mentioning some of the same cases and reports that were blown out of proportion by the DEA, the review states that “These examples demonstrate the need for screening and sufficient preparation prior to ayahuasca sessions as some people with underlying health conditions including a personal or family history of psychosis are at greater risk… However, regular use in healthy individuals has not been associated with deterioration of mental health or cognitive function and incidences of psychosis in ayahuasca users are reported to occur in less than 0.1% of consumers.”

“regular use in healthy individuals has not been associated with deterioration of mental health or cognitive function and incidences of psychosis in ayahuasca users are reported to occur in less than 0.1% of consumers.”

Edward James, Joachim Keppler, Thomas Robertshaw, and Ben Sessa, “N, N-dimethyltryptamine and Amazonian Ayahuasca Plant Medicine,” Human Psychopharmacology 37(3), May 2022.

The article points out that ayahuasca is generally used in group settings and that the supportive community environment likely plays an important role in the effectiveness of ayahuasca as a medicine. The article stresses that this should serve as inspiration for biomedicine, should the drink ever be included among licensed therapies.

The authors recommend that “if ayahuasca is to be integrated fully into international medical systems, practitioners to be based outside the Amazon should be trained medical doctors, psychiatrists or psychologists who could specialize and receive complementary training in the Amazon.”

They cite as possible mentors for the European and US health professionals no less than leaderships from Shipibo-Conibo, Tukano, Kamsa, and Huitoto, some of the many Amazonian Indigenous peoples who traditionally use the drink and “who have been asserted as being Amazonian equivalents of institutions such as Oxford, Cambridge and Harvard.”

It seems highly unlikely that the DEA will include this survey in its next internal report on ayahuasca’s public health and safety risks. The recognition and tribute due to traditional knowledge do not fit within the narrow scope of instrumentalizing science as weaponry in their failed War on Drugs.

Note:

Originally published in Portuguese by Folha de São Paulo on the blog Virada Psicodélica HERE.

Art by Mariom Luna.

Take a minute to browse our stock:

Did you enjoy reading this article?

Please support Chacruna's work by donating to us. We are an independent organization and we offer free education and advocacy for psychedelic plant medicines. We are a team of dedicated volunteers!

Can you help Chacruna advance cultural understanding around these substances?