- Hallucinating Hierarchies: How Patriarchy Co-opts Psychedelics - July 7, 2025

- Queering Psychedelics: An Introduction - August 7, 2024

- Introduction to Women and Psychedelics - July 26, 2024

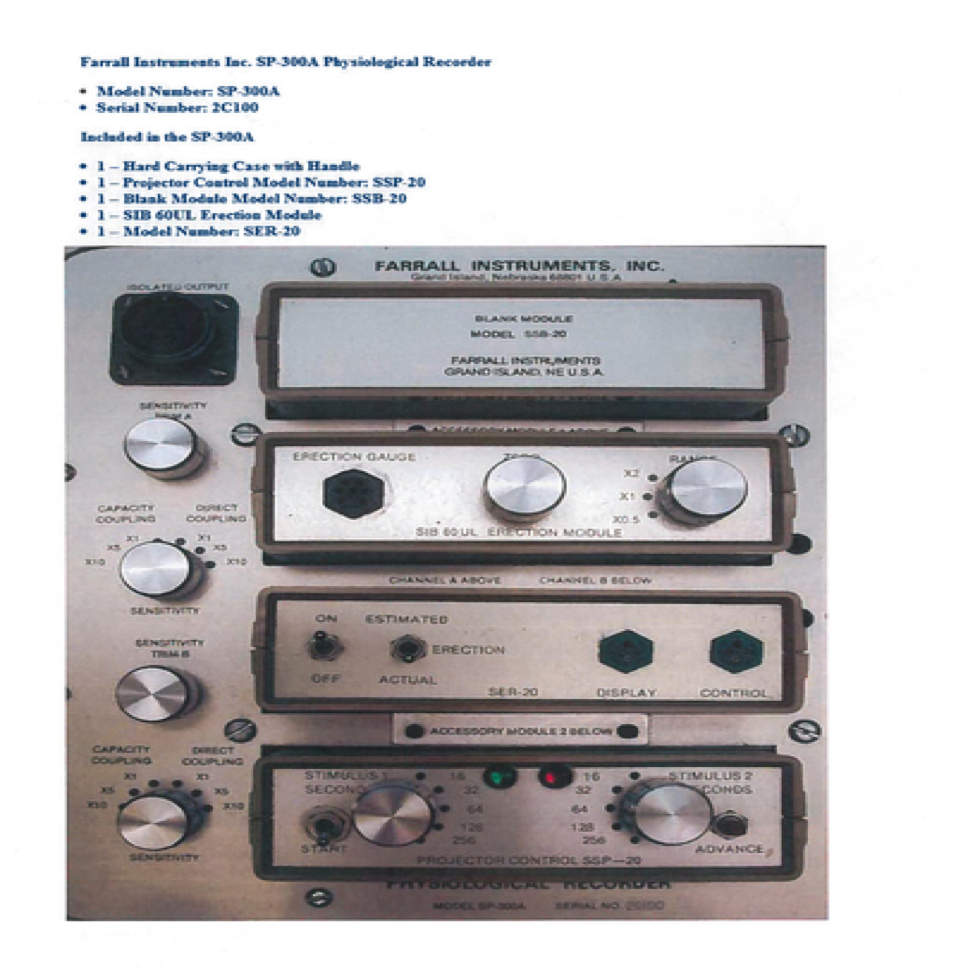

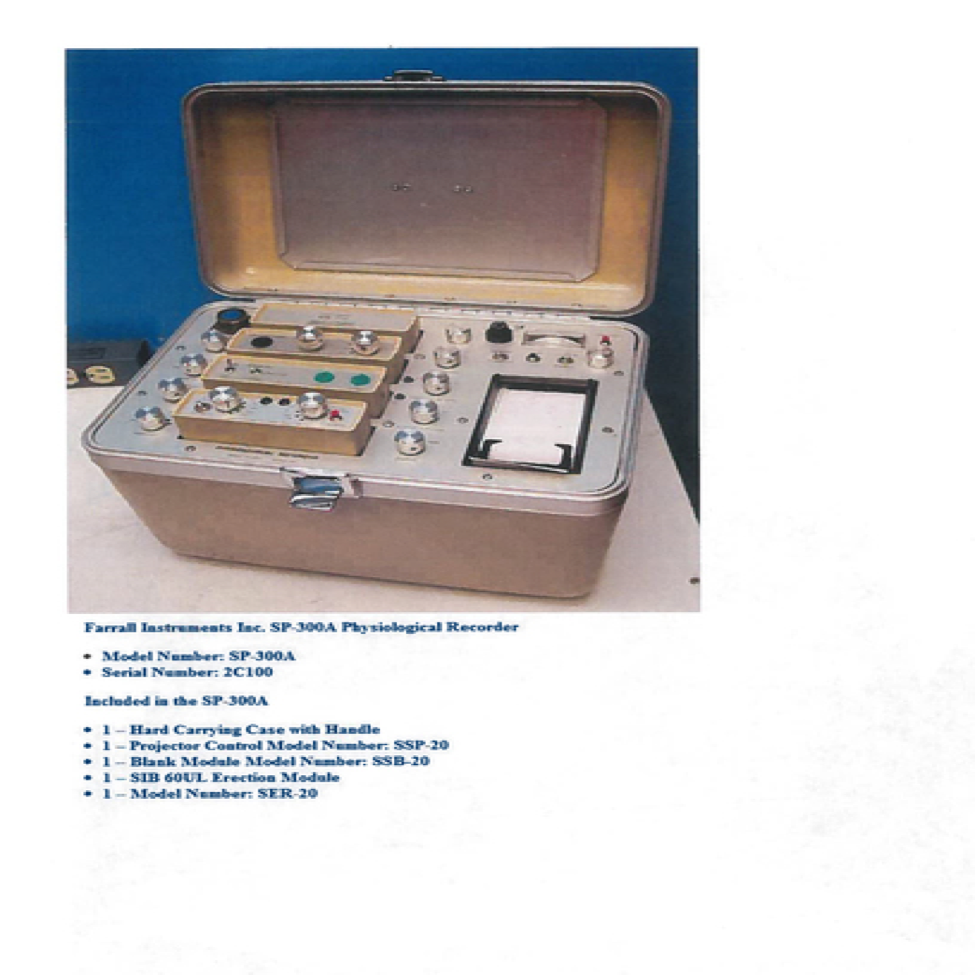

one early use of psychedelics by psychologists was in attempts to treat homosexuals to change their sexual orientation

Although it is common for people currently to express the opinion that psychedelics will open people’s minds, making them less judgmental and more able to share love and be inclusive, one early use of psychedelics by psychologists was in attempts to treat homosexuals to change their sexual orientation. “Conversion therapy” is a treatment that attempts to change the sexual orientation of homosexuals. This practice became more controversial after the removal of homosexuality from the DSM in 1973.1 If homosexuality is no longer an illness, what justification could there be for treating it?

In 2016, for the first time, the Republican Party endorsed conversion therapy in their platform under “right of parents to determine the proper medical treatment and therapy for their minor children.” Conversion therapy, or “reparative therapy,” is illegal in only 16 states, and has been promoted in the past by current Vice President Pence, who said, “Resources should be directed toward those institutions which provide assistance to those seeking to change their sexual behavior,”2 though he currently denies his support.3

Freud believed all humans were born bisexual, and that their later preferences were the results of life experiences and conditioning from parents. “Homosexuality is assuredly no advantage, but it is nothing to be ashamed of, no vice, no degradation, it cannot be classified as an illness… It is a great injustice to persecute homosexuality as a crime, and cruelty too.”4 Kinsey also normalized homosexuality by creating the “Kinsey Scale” and expressing sexual orientation on a continuum. However, in the 50s, with the advent of behaviorism, the idea that homosexuality was a learned behavior was introduced, and so treatment to cure it with behavioral interventions, including aversion therapy, the pairing of a painful event with the behavior that is desired to be extinguished.

The opinion of the American Psychological Association (APA) is that there are no safe or effective ways of changing someone’s sexual orientation, and therapies that claim to do so can reinforce negative views of homosexuality and be harmful to the client.5 The ethical foundation for treating individuals with socially undesirable traits with powerful psychedelic compounds to rid them of these traits is highly suspect. This article is a reminder that all medicines can be poison in the wrong hands.

Sexual Minorities and Treatment with Psychedelics

A study by Alpert6 was one of the earliest reports in the literature on sexual minority experience with psychedelics. It is one example of conversion therapy found in the literature (see also, Masters & Houston, 2000; Martin, 1962; Stafford & Golightly, 1967). Alpert administered 200 micrograms of LSD-25 to a male self-identified bisexual volunteer who was dissatisfied with his attraction to men. During his fifteen-hour trip, the subject was shown pictures of women and encouraged to develop feelings toward them. In subsequent LSD sessions, a woman the subject knew was present and he had sexual intercourse with her. One year after the treatment, Alpert reported that the man was living with a woman, but had had two subsequent homosexual encounters, which the subject described as tests of himself to see if the changes he had experienced because of the treatment were “real.” Alpert explained that the use of LSD allowed the subject to take a broader view of the archetype of “woman” and find connections to primal desires within the archetype, which he could then generalize to all women.

Stanislav Grof treated homosexual clients with LSD. He concluded that gay men’s dislike of sex with women was related to images of “vagina dentate” and castration fantasies that were envisioned during LSD sessions

Stanislav Grof7 treated homosexual clients with LSD. He concluded that gay men’s dislike of sex with women was related to images of “vagina dentate” and castration fantasies that were envisioned during LSD sessions. He related lesbianism to the desire to be close to the mother. Grof admits that he has treated mostly homosexuals who were dissatisfied with their orientation, and that a healthy adjustment to same-sex orientation is possible and may not represent intra-psychic struggle. Grof also noted that subjects in LSD treatments often saw their sexuality in archetypal or transcultural ways, such as witnessing fertility rites, initiation ceremonies, and temple prostitution.

They found that by taking psychedelics, the body image distortion was corrected, and they observed a trend toward “heterosexualization”

In The Varieties of Psychedelic Experience, Masters and Houston8 reported giving the psychotropic cactus peyote to a group of gay volunteers. Working from the assumption that homosexuality is an undesirable orientation, Masters and Houston attempted to treat their gay clients with repeated doses of peyote. They reported that 12 out of 14 male homosexual volunteers in a psychedelic experiment had distorted body images that the researchers contended to be causal to homosexuality, although they admitted they could not prove this. They found that by taking psychedelics, the body image distortion was corrected, and they observed a trend toward “heterosexualization.” They also speaks stereotypically of the passivity of the homosexual man being transformed by psychedelic therapy, and attribute a deepening of the voice, greater vigor, improved posture, and greater masculinity to treatment with peyote. They found that the participants displayed a greater desire to appreciate their appearance after the peyote experience. In one case reviewed by Masters and Houston, the researchers were discouraged by their subjects “considerable investment in his homosexuality” and felt unable to capitalize on the “gains” made in therapy (p.200). They proceeded to speculate on the progress they might have made had the subject been more motivated to become heterosexual.

A study by Martin (1962) looked at the effects of LSD on twelve gay men. Martin recommended LSD as a treatment for homosexuality. Administering many low doses in a treatment known as psycholytic (“mind-separating”) therapy and encouraging intense mother-transference, Martin claimed that seven out of twelve achieved heterosexual orientation with only one “slight relapse” in a 3 to 6-year follow-up (Sandison, 2001).

Stafford and Golightly (1967) reported on LSD therapy for homosexuals during the 1960s. They found that homosexual issues were often resolved using psychedelic therapy, and that homosexuals would either be at peace with their orientation after LSD therapy or decide that they were heterosexual. Stafford and Golightly viewed homosexuality to be a result of early childhood trauma and “morbid dependency”on parents, both of which could be treated with regressive “shock therapy” with LSD. Stafford and Golightly recommended that LSD be used to treat transvestism, fetishism, and sadomasochism in the same way that it could be used to treat homosexuality. Masters and Houston also advocated LSD, stating, “Treatment of sexual disorders—frigidity, impotence, homosexuality and fetishism—and some other neuroses has many times been described as both drastically shortened and made more effective when LSD was used as an adjunct to psychotherapy” (Masters & Houston, p. 39). This view reflects the thinking current in the late 60s, in which homosexuality was viewed as a mental disease, related to paraphilias.9

Personal Accounts

Rare personal reports of individual therapeutic entheogenic experiences of sexual minorities can be found in the past literature prior to the current psychedelic renaissance. First-person stories about self-administered entheogenic experiences by gays and other sexual minorities help expand the story. Some examples from before the latest psychedelic renaissance include are port made by a “post-op” transgender woman10 describing her most recent experience using LSD. She and a “pre-op” transgender woman agreed to take LSD and, at the peak of their experiences, they agreed they would look at themselves naked, side by side in a full-length mirror, “We would look to see whether we were monsters or whether we were God’s beautiful creatures. And through the wide open doors of perception, we saw the truth: We were beautiful.”11

Berkowitz, 12 a lesbian, wrote about encountering her grandmothers in a vision during an ayahuasca experience on her 30th birthday. She concluded her report by saying that she felt she had “reclaimed (her) life”.

Merkur13 described a man who took LSD and was able to integrate and accept the fact that he had had homosexual experiences in the past; experiences he had previously been unable to reconcile with his self-image. He came to the conclusion that it was not a “big deal” and, during this experience, he was able to perceive himself in anon-judgmental way that proved healing for him.

Annie Sprinkle14 a bisexual sex worker, educator, and performer, wrote about her experiences with drugs and entheogens. She had not tried ayahuasca, but had taken “pharmahuasca,” a combination of chemical and natural sources of DMT and MAOI. She related that she felt that experience was preparing her for her death. Her experiences lead her to the conclusion that entheogens can have a role in sex therapy because they can help individuals gain a fresh perspective on their identity. She posits that sexuality and the use of entheogens are both about consciousness and self-discovery.

my dissertation work on gay people and ayahuasca, show that gay people can benefit from psychedelic use to heal from cultural homophobia

These and other examples throughout time, including my dissertation work on gay people and ayahuasca, show that gay people can benefit from psychedelic use to heal from cultural homophobia. Psychedelics are rightfully used to “manifest mind,” not to warp it, as these efforts at conversion therapy and other reckless uses, such as in MK Ultra experiments, reveal. It is important and timely to raise awareness of how agendas may color the conceptions and uses of psychedelic medicines; a relevant topic as the market begins to form around psychedelics once again.

References

- Drescher, J. & Zucker, K. J. (2006). Ex-gay research: Analyzing the Spitzer study and its relation to science, religion, politics, and culture. Philadelphia, PA: Haworth Press. ↩

- Stack, L. (2016, November 30). Mike Pence and ‘conversion therapy’: A history. The New York Times. ↩

- Groppe, M. (2018, February 16). After Rippon: Searching for clarity on Mike Pence’s stance on gay conversion therapy. Indystar.com. Retrieved from https://www.indystar.com/story/news/politics/2018/02/16/after-rippon-searching-clarity-mike-pences-stance-gay-conversion-therapy/343105002/. ↩

- Freud, S. (1951). A letter from Freud. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 107,786–787. http://dx.doi.org/10.1176/ajp.107.10.786. ↩

- American Psychological Association. (2008). Answersto your questions: For a better understanding of sexual orientation and homosexuality. Washington, DC: Author. Retrieved December 4, 2008 from http://www.apa.org/topics/sorientation.pdf. ↩

- Alpert, R. (1969). Drugs and sexual behavior. The Journal of Sex Research, 5(1), 50–56. ↩

- Grof, S. (2000). The psychology of the future: Lessons from modern consciousness research. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press. ↩

- Masters, R. & Houston, J. (2000). The varieties of psychedelic experience.Rochester, VT: Park Street Press. ↩

- Suppe, F. (1984). Classifying sexual disorders. Journal of Homosexuality, 9(4), 9–28. ↩

- Denny, D. (2006). A word from the editor: The last time I dropped acid. Transgender Tapestry, 110, 63. ↩

- Denny, D. (2006). A word from the editor: The last time I dropped acid. Transgender Tapestry, 110, 63. ↩

- Berkowitz, J. (2008). Word to the mother: How Igave it up on my 30th birthday (I tried it). Curve, 77(1). doi A179885525. ↩

- Merkur, D. (2007). A psychoanalytic approach to psychedelic psychotherapy. In M. J. Winkelman & T. B. Roberts (Eds.), Psychedelic medicine: New evidence for hallucinogenic substances as treatments (pp. 195-211). Westport, CT: Praeger. ↩

- Sprinkle, A. (2003). How psychedelics informed my sex life and sex work. Sexuality and Culture, Spring, 59–71. Retrieved from https://maps.org/news-letters/v12n1/12109spr.html. ↩

Take a minute to browse our stock:

Did you enjoy reading this article?

Please support Chacruna's work by donating to us. We are an independent organization and we offer free education and advocacy for psychedelic plant medicines. We are a team of dedicated volunteers!

Can you help Chacruna advance cultural understanding around these substances?