- After 2024, the Scenario for Psychedelic Therapies Can Only Improve - January 16, 2025

- Symposium in Brazil Debates Psychedelics at a Political Crossroads - December 13, 2024

- Conference in Rio Defends Psychedelics in Public Health - December 11, 2024

A wild Mustang and plant medicines have saved Itzel Barakat from the societal gutter she was lying in. Libby (short for Liberation), the Mustang rescue, bowed her head to be stroked, showing her human counterpart acceptance and unconditional love. Then, the veteran with two tours to Afghanistan burst into sobs. “I felt seen for the first time in my life,” Barakat told the audience at the Brava Theater Cabaret in San Francisco, where track 2 of the conference Queering Psychedelics II was taking place on April 22 and 23 (QP2, in short).

Barakat is a Panamanian American, born in the U.S., who emigrated to Panama at eight years old with her parents. As she struggled to adjust to big changes and find her identity, she faced returning to the U.S. and having to readjust, again, only five years later; too many adjustments for a teenager already experiencing conflict due to being queer in a conservative family.

For Barakat, the military was an escape route she took to move away from her oppressively religious family. She joined the Air Force at the age of 19, in search of a community to belong to and to serve a greater good. However, upon exiting the military, there was no safety net or plan, and Barakat experienced extreme difficulty in her transition from the service; a downhill trajectory that stopped once she crossed paths with Libby.

The encounter with Libby took place a year after Barakat had experienced homelessness in Los Angeles, sleeping in her car with a dog. After six years in the Air Force, she transitioned to wildland firefighting, battling wildfires in California, an occupation that proved even more stressful than providing administrative help to combat pilots, leading this queer woman into one of the darkest times in her life.

On her birthday in 2017, with little understanding of PTSD symptoms, she reached out for help to the Veterans Administration (VA), and began her road to healing and getting back on her feet. In 2018, while attending Pasadena City College, she was asked to be part of a veteran volunteer group that was assigned to an animal rescue in Idyllwild, California, where she met Libby and started working with the equine program at War Horse Creek.

Her mentor, a former marine who was also a writer, was someone that made a deep impact on her life. He counseled Barakat and encouraged her, telling her she would make a hell of a therapist. She had many conversations like this with him before he took his own life in 2020, an event that rekindled all the grief she had experienced after the death of her father.

As she continued her healing journey with the VA, her talent for helping other veterans was noticed. They put her in touch with Veterans of War, an organization that provides the opportunity for veterans to work with traditional plant medicines and would take her to Costa Rica for an ayahuasca ceremony.

“It was incredible to feel that much community and support, as we all experienced the collective healing together. It is such a unique experience in psychedelic medicine,” she recalls. “Psychedelic medicines have a way of mapping you away from the separation and connecting you closer to people of all walks, queer or not. We were standing as giants among each other.”

It’s been now three years on the path to become a psychedelic-assisted therapy (PAT) facilitator for veterans. Barakat is just finishing her undergrad training in psychology and is about to start graduate school.

Join us for our Ayahuasca Healing, Science and Indigenous Knowledge Course, May 22 – August 21, 2023

“Meeting Libby was my first psychedelic ceremony,” says the 38-year-old veteran. The plan now is to expand both equine therapy and PAT beyond the circle of peers to include first responders, emergency medical technicians, law enforcement, queer individuals, and communities of color under her care, she told me over lunch at Taquerias El Farolito on 24th Street, not far from the Brava Theater.

Barakat’s was just one of many moving stories to be heard at QP2, four years after the first pioneering conference at the vibrant intersection of psychedelics and queerness. It was organized again by the Chacruna Institute, a nonprofit led by Bia Labate and Clancy Cavnar (disclaimer: I’m on its advisory board). The two-day gathering attracted 345 members of the LGBTQIA+ community and their allies to the Brava Theater Center, in San Francisco’s multicultural and colorful Mission District. Here are the opening remarks by Cavnar.

Not the vanilla kind of psychedelic conference, to be sure. Not so much talk of clinical trials results, research protocols, FDA approval or market and investment strategies. Instead, most of the presentations and testimonies revolved around overcoming truckloads of trauma, violence, shame, self-hatred, and guilt; frequently, with the aid of psychedelics—an opportunity as well to discuss the unique needs of queer people in psychedelic trials and therapies. It is, in many ways, a perfect match; not only because psychedelic research has been proving the potential of ayahuasca’s DMT and mushroom’s psilocybin to treat the depression, substance abuse, anxiety, and PTSD that so often afflict queer folks, but also because, at their roots, queerness and psychedelics have a lot in common.

Here is a sample of words and expressions that kept popping up in QP2 … fun, brilliance, solidarity, oceanic love, alternate realities and identities, self-knowledge and acceptance, freedom, fluidity, playfulness, pleasure, community… However, there is always a downside, and the psychedelic field has been the source of a lot of suffering and harm for LGBTQIA+ people.

Here is a sample of words and expressions that kept popping up in QP2 and could refer to both crowds: ability to have fun, brilliance, solidarity, oceanic love, alternate realities and identities, self-knowledge and acceptance, freedom, fluidity, playfulness, pleasure, community… However, there is always a downside, and the psychedelic field has been the source of a lot of suffering and harm for LGBTQIA+ people. There are skeletons to come out of the closet, too, and not everything is gold under both ends of the rainbow.

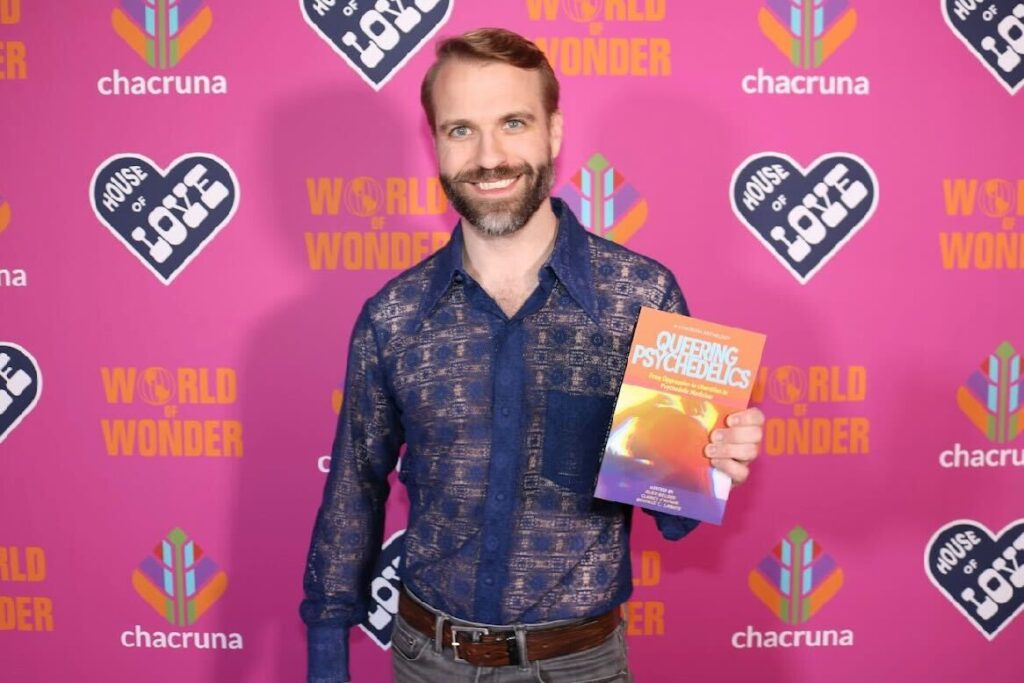

Conversion therapy, the elephant in the theater, was pointed out by, among others, Alex Belser, who co-edited the book Queering Psychedelics – From Oppression to Liberation in Psychedelic Medicine, together with Cavnar and Labate. Belser is a licensed psychologist and researcher focused on psilocybin, MDMA, and DMT therapies at Yale, where he is investigating a psychedelic treatment for OCD. His scathing speech at QP2 carried the title “Dear Straight Psychonauts: An Open Letter to Cishet Folks in the Psychedelic Community from a Queer Researcher.”

Join us for our Roots of Psychedelic Therapy: Shamanism, Ritual and Traditional Used of Sacred Plants course, August 8th – November 21st, 2023

He called upon psychedelic scientists to take notice that, in spite of all the visibility acquired by LGBTQIA+ issues, life is getting worse for young queers in many places. Hormonal and surgical treatments are now forbidden for minors in 15 states. Florida has recently banned discussion of gender identity and sexuality in classrooms, already limited in a dozen other states. In Tennessee, the law prevents drag performances in public spaces or in the presence of children, including the popular convention in some places of Drag Queen Story Hour in libraries.

“I feel more than grief, more than anguish,” said Belser. “I feel anger. Anger is not a bad emotion.”

It is currently estimated that 698,000 LGBT adults have been submitted to some form of conversion therapy, and 73,000 under the age of 18 are at risk of receiving it in the states that haven’t yet outlawed this type of heteronormative violence. Less known and acknowledged is the fact that LSD and mescaline have been widely used as an adjunct to conversion therapy, based on the presumption that they would unblock childhood traumas supposedly at the root of what was considered a disease or deviant behavior. Conversion therapy was championed even by heroes in the psychedelic pantheon such as Timothy Leary, who once touted LSD as “a specific cure for homosexuality,” and Richard “Ram Dass” Alpert and Stanislav Grof, who reported cases of male homosexual patients treated with psychedelics to change their sexual orientation.

“The psychedelic community has been an accomplice. It is time for reckoning [in the psychedelic research field], to acknowledge its own responsibility. I ask my psychedelic straight friends: Ban conversion therapy.”

Alex Belser

“The psychedelic community has been an accomplice,” denounced Belser. “It is time for reckoning [in the psychedelic research field], to acknowledge its own responsibility. I ask my psychedelic straight friends: Ban conversion therapy.”

According to Belser, these are not only horrors of the past, as heteronormativity still pervades practices in the research community. Most of PAT protocols recommend a male-female therapist dyad for dosing sessions, a provision once intended to prevent sexual abuse of patients by male therapists that nowadays is seen as essentializing retrograde notions of masculinity and femininity. Moreover, the binary dyad privileges cisgender therapists to the detriment of trans, non-binary, and gender-nonconforming practitioners. “To queer this outdated care protocol, we must foreground a patient-centered treatment approach that matches therapy pair assignment based upon the specific history and needs of each patient,” advocate Belser and co-author Ava Keating in the first chapter of the book Queering Psychedelics. In his talk, Belser proposed the adoption of a Psychedelic Equity Index to render clinics and research organizations accountable.

The fight for culturally competent care extends to the collection of data by psychedelic researchers. “It is OK to enroll queer people in clinical trials, but you have to collect and report their data,” demanded Belser, based on the truism that not every treatment will lead to the same clinical outcomes for each population. But there is currently no research aiming to determine what is best for treating LGBTQIA+ patients. The psychedelic field can, and must, do better, beginning with performing data aggregation and meta-analysis for LGBTQIA+ populations across studies, he states.

“The master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house,” summarized Belser, quoting famous words from feminist author Audre Lorde. He called “queer siblings to shine like a true hallucination,” and to stand up like predecessors did in the ACT UP (Aids Coalition to Unleash Power) movement, who popularized the phrase “silence = death,” because silence is all he gets from research peers who don’t actually disagree with queer people’s rights and demands but change nothing in their methods to accommodate them.

Hope, resilience, a sense of community, and mobilization gave a generally uplifting tone during talks at QP2, although with many painful testimonies in between. One of the most emotional talks was given by Taylor Dahlia Bolinger, a trans woman social worker in Texas, of all places. “Psychedelics didn’t heal me. Transition healed me,” were some of the first poignant words she had for the audience in the Brava Cabaret. “I will not leave Texas. I owe it to those [LGBTQIA+] kids,” she said with a trembling voice, visibly holding tears back.

Bolinger informed her audience that 86% of psychiatrists in her state are not competent to work with trans people. “If the psychedelic community want to heal the world, they have to transcend the colonized notions of gender,” she declared, lamenting that she feels radically alone in the field. One example is the exclusion and heteronormativity preventing her from attending ceremonies of the UDV (União do Vegetal) ayahuasca church because of stereotypical gender roles ingrained in the religion’s doctrine (the UDV condemns homosexuality, for instance, and does not accept women in the upper tier of hierarchy, that of “masters” who are allowed to lead rituals). “We don’t have to attend ceremonies run by people who will never acknowledge our identity.”

“We don’t have to attend ceremonies run by people who will never acknowledge our identity.”

Taylor Bolinger

Diversity of experiences, though, was another hallmark of the QP2 conference. Consider the case of Clancy Cavnar, a queer woman married to Bia Labate and co-founder, with her, of the Chacruna Institute, who gave a paradoxically divergent testimony about her attending rituals at another church, Santo Daime, for the last 26 years. In spite of being a sharp critic of homophobia in ayahuasca religions and shamanism, she told a story of finding solace and acceptance from congregations that, in many aspects, conflict with her own values and beliefs.

“It is fully ironic to me that this foundation [Santo Daime’s] has its roots in Christianity,” Cavnar admitted, “a force that has been so harmful in the world to so many, the handmaiden of colonialism and a current political force that, in its current form, is opposed to queer people and women’s rights and represents a patriarchal, conservative force that is dangerously apocalyptic.”

Religion had no role in Cavnar’s life until her 30s, when she renewed an interest in Buddhism with a trip to a Tibetan monastery in Nepal for a month. Soon after that, she attended a Santo Daime ceremony that was produced for a class in the East-West Psychology Department at the California Institute of Integral Studies and came out of it eager to repeat the experience. A summer trip to learn Spanish in South America was then extended to encompass a detour to the epicenter of Santo Daime in Brazil, Céu do Mapiá. She took part in rituals with hundreds of people dancing all night long several times during a month.

“It was completely weird, and I had no idea what they were singing.” She recalled being very strongly affected by the ayahuasca, spending hours in the healing room away from the main area, under the sway of powerful visions. Women prayed over her, told her to think of the Virgin Mary while having a hard passage, anointed her with ayahuasca in a cross on the forehead, or gave her marijuana for pacification.

During this time, far away from familiar things, deep in the jungle, she began to have visions of Jesus and Mary: “I saw them in Heaven and I saw Jesus on the cross, a strong wind blowing dark clouds across the sky. I felt the sadness Jesus felt when his apostles left him. I started to think that I must be a Christian and this is what Christians discover, these feelings of love and sadness connected with the unjust murder of a saint,” she told the QP2 crowd. “I at least started to give Christianity a chance, seeing that it could evoke feelings of tenderness and love and even spiritual ecstasy, when combined with the right drug.”

Under the influence of ayahuasca Cavnar has had visions that she captures in colorful, sometimes dark paintings. One goddess showed her two years ago the sheer impact of patriarchy: the exploitation of people, the rush to use up all resources, the denigration of women by men, slavery, racism, and so on. In spite of knowing the general concept of patriarchy, before the fatalistic vision, she hadn’t fully grasped its depth and prevalence. However, the goddess also told her not to despair: “Regardless of this unfortunate condition, all was well in the universe, which would continue with or without humans on Earth.”

“I want difference, I want a strong, strange force to change me; I don’t want to be lulled into comfort, I don’t want to be comfortable because I am not doing a comfortable thing: I am performing a strange ritual with a magic potion to heal myself.”

Clancy Cavnar

Apart from Santo Daime, she has attended many shamanic ceremonies in Peru, Brazil, Ecuador, and Costa Rica, and quite a few “hippie” ceremonies in the USA, more unstructured and less doctrinal, but always feels bored by the latter. She doesn’t mind the segregation of men and women during rituals, nor the prescribed uniforms. She loves to sing Santo Daime “hinos” in their original language, Portuguese, and is therefore against translating the lyrics to English in order to make ceremonies more palatable for Americans. “I want difference, I want a strong, strange force to change me; I don’t want to be lulled into comfort, I don’t want to be comfortable because I am not doing a comfortable thing: I am performing a strange ritual with a magic potion to heal myself.”

Mutatis mutandi, Cavnar’s words capture almost exactly how a straight male reporter felt during two memorable days at the Brava Theater Center –healed, although no magic potion was being served during the conference besides rapé (tobacco snuff), coffee, and chocolate. Healed by hope, resilience, and a strong sense of community.

Art by Trey Brasher.

Join us for our The Science of Psychedelic Healing course, June 6th – August 1st, 2023

Take a minute to browse our stock:

Did you enjoy reading this article?

Please support Chacruna's work by donating to us. We are an independent organization and we offer free education and advocacy for psychedelic plant medicines. We are a team of dedicated volunteers!

Can you help Chacruna advance cultural understanding around these substances?