- After 2024, the Scenario for Psychedelic Therapies Can Only Improve - January 16, 2025

- Symposium in Brazil Debates Psychedelics at a Political Crossroads - December 13, 2024

- Conference in Rio Defends Psychedelics in Public Health - December 11, 2024

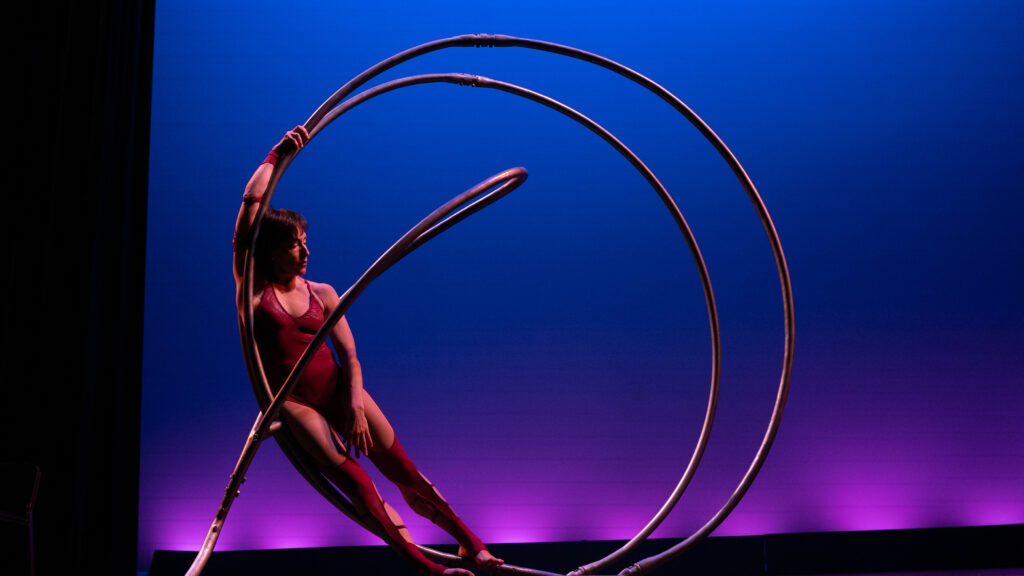

A magical vision crowned the first day of the Chacruna Institute’s Psychedelic Culture 2024 conference in San Francisco: the dance performance Perfect Flower by Jodi Lomask. A combination of acrobatic and poetic acts, it offered an eloquent metaphor for the tensions and possibilities that mark the so-called psychedelic renaissance.

The two-day event at the Brava Theater attracted 446 participants. A total of 87 speakers and moderators presented in dozens of panels divided into three rooms. (As a guest of Chacruna, an NGO run by Brazilian anthropologist Bia Labate, I took part in two of the discussions).

Lomask explained that a perfect flower is one that has both male and female reproductive organs. The lines of the apparatus she designed and used in her choreography evoked schematically fused human genitalia, representing a self-sufficiency that the dancer and choreographer had to find during the isolation of the pandemic, as she recounted.

It will take much more than acrobatics to realize the conference’s proposal, a dialogue between Indigenous peoples who make ancestral use of plants and psychoactive fungi and biomedicine, which has resumed research into the therapeutic use of substances such as dimethyltryptamine (present in ayahuasca) and psilocybin (from so-called “magic” mushrooms) in the twenty-first century.

Labate said at the opening that the idea of a “global psychedelic community” encompassing Indigenous peoples, religious groups, shamans, psychonauts, and scientists is far from reality. All have rights and demands, but some seem to be more successful than others in having those respected.

“Stigmatization, pathologization, and criminalization have worked hand-in-hand to threaten minority rights, persecute traditional populations, and, of course, exploit their territories and resources.”

Bia Labate, Psychedelic Culture 2024 Opening Remarks, April 2024

“Stigmatization, pathologization, and criminalization have worked hand-in-hand to threaten minority rights, persecute traditional populations, and, of course, exploit their territories and resources,” she said. “This has also led to the mass incarceration of people of color.”

For her, the psychedelic revival should not be solely a medicalized version, or only for the elite. Labate rejected the notion of a psychedelic “industry,” “populated by sham experts, opportunists, charlatans, cult leaders, potential abuse, and shameless commercialization.”

Wear the Movement. Explore our Collection of T-Shirts.

Perhaps the word most used at the conference was “dialogue,” under the premise that Indigenous people, guardians of plants and fungi for centuries or millennia, must participate in the conversation. This is often a difficult exchange, of course, as it seems that many traditional groups are more open to it than academics and psychedelic research corporations.

Chacruna’s conference featured Indigenous speakers such as the Native-Brazilian Adana Omágua Kambeba, one of the most applauded. In her individual presentation, one of the few at the meeting, the trained doctor with a medical degree from the Federal University of Minas Gerais (UFMG) told us that she is finishing a rigorous seven-year diet to become a shaman.

With this background, she took a hard line with non-Indigenous people who call themselves shamans. It is not because one has attended Indigenous ayahuasca rituals in the Amazon, even for months at a time, that one has earned the right to strut around as shamans, or other such self-designated titles.

At the panel on Indigenous shamanism that I moderated, she moved the audience by narrating the situation she experienced at the Sofia Feldman hospital in Belo Horizonte, Brazil, when an Indigenous baby was admitted with sepsis. Doctors tried to convince the parents and the shaman present that they needed to intubate the child and give him antibiotics.

Faced with a strong refusal, the hospital called for Adana. As she entered, everyone turned their eyes to her as their last hope. As a doctor, however, she knew that the baby was about to die. Thus, she chanted a “rezo” (prayer) and, talking “in the Indigenous way,” got the parents and the shaman to authorize the Western medical procedures. In the end, the child was saved; the Indigenous people were certain that it was because of the prayer, and the doctors, because of their intervention.

Happy encounters like this are rare, as are Indigenous people with Adana’s dual training and the ability to move between healing cultures. The psychedelic movement undoubtedly needs more hybridity like this. With such nourishment, more perfect flowers could flourish.

Note: The original version of this article was published on Folha de S.Paulo. Translated into English by Henrique Antunes.

Art by Karina Alvarez.

Check out our new “Cultivating Roots for Cultural Change” T-Shirt!

Take a minute to browse our stock:

Did you enjoy reading this article?

Please support Chacruna's work by donating to us. We are an independent organization and we offer free education and advocacy for psychedelic plant medicines. We are a team of dedicated volunteers!

Can you help Chacruna advance cultural understanding around these substances?