- Participation in an Indigenous Amazonian-led Ayahuasca Retreat Associated with Increases in Nature Relatedness – A Pilot Study - March 21, 2024

- A Phenomenology of Subjectively Relevant Experiences Induced by Ayahuasca in Upper Amazon Vegetalismo Tourism - November 9, 2023

- The Pharmacological Interaction of Compounds in Ayahuasca: A Systematic Review - October 26, 2023

Netzband, N., Ruffell, S., Linton, S., Tsang, W. F., & Wolff, T. (2020). Modulatory effects of ayahuasca on personality structure in a traditional framework. Psychopharmacology, 237(10), 3161-3171. DOI 10.1007/s00213-020-05601-0

- Study Rationale

- Methodology

- Summary of Results

- Personality changes from baseline to post-treatment

- Figure 1

- Relationship between neuroticism, agreeableness, and mystical experience

- Personality changes from post-treatment to follow-up

- Figure 2

- Integration with extant literature

- Expectancy Effects

- Study Relevance

- References

Study Rationale

Whilst the numbers of tourists visiting the Amazon rainforest to drink ayahuasca continues to increase, relatively few studies have evaluated the psychological impact of the brew in such settings. Open label studies suggest that psychedelics such as psilocybin may increase the personality facet of Openness and decrease that of Neuroticism (Erritzoe et al., 2018; MacLean et al., 2011). While previous research has evaluated the effects of ayahuasca on personality (Barbosa et al., 2009; Barbosa et al., 2016; Bouso et al., 2012; Grob, 1996; Kavenská & Simonová, 2015), this is, to my knowledge, the first study to collect prospective personality data in a traditional Shipibo-style retreat setting.

Open label studies suggest that psychedelics such as psilocybin may increase the personality facet of Openness and decrease that of Neuroticism.

Methodology

Using the NEO-PI3 personality questionnaire (Costa Jr & McCrae, 2008), 24 participants were assessed alongside a comparison group, immediately before drinking ayahuasca, after their 12 day retreat and at six-months to assess for longer term changes. Comparison group participants were English-speaking individuals on holiday in Peru who were initially approached on the premise that they had no previous experiences with ayahuasca reported. The Mystical Experience Questionnaire (MEQ; Barret et al., 2015) was administered at time-point two to assess the degree to which participants underwent a mystical experience, which was subsequently correlated with changes in personality. Written consent and demographic information were obtained the day before the first ayahuasca ceremony. The six-month follow-up NEO-PI3 scores were obtained electronically via email. This also included a follow-up questionnaire assessing the potential long-term impact of the retreat in terms of behavioural, physical, and psychological changes.

Summary of Results

Personality changes from baseline to post-treatment

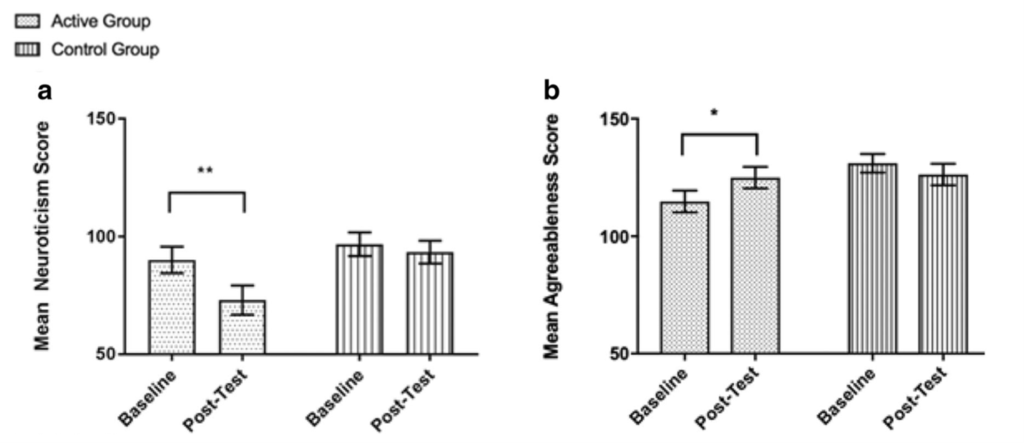

Our team first assessed whether the ayahuasca sessions led to changes in personality from baseline to post-test, using a mixed ANOVA, with time (baseline, post-test) and personality (neuroticism, extraversion, conscientiousness, agreeableness, openness to experience) as the within-participants variables, and group (active vs. comparison) as the between-subjects variable. To correct for multiple comparisons, the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure (Benjamini & Hochberg, 1995) was applied for all follow-up pairwise comparisons. Analysis observed a significant interaction between time, personality, and group. Pairwise comparisons revealed a significant reduction in Neuroticism scores from baseline measures to post-test in the active group (d = 0.59, p < .001), but not the control group (p = .335). Pairwise comparisons also revealed a significant increase in Agreeableness scores from baseline measures to post-test in the active group (d = 0.45, p = .012), not the comparison group (p = .222) (Figure 1). Given that there were non-significant differences in baseline Agreeableness and Neuroticism scores between the active and comparison groups, our results suggest a significant reduction in Neuroticism and a significant increase in Agreeableness in the active group following the ayahuasca sessions. Consistent with our original hypothesis, there was a trend towards a significant increase in Openness scores from baseline to post-test in the active group (p = .040); however, this test did not survive the correction for multiple comparisons.

Figure 1

Significant reduction in Neuroticism (a) and increase in Agreeableness (b) observed in the active group from baseline to post-test, compared with the comparison group. Asterisk indicates p < .05, double asterisk indicates p < .001. Bars represent the standard error of the mean (SEM).

Relationship between neuroticism, agreeableness, and mystical experience

Spearman’s rank-order correlation revealed a medium significant negative correlation between Neuroticism change and MEQ scores from baseline to post-test in both the active and comparison groups (rs(48) = − .56, p < .001) (i.e. those who reported a greater degree of mysticism also experienced greater reductions in Neuroticism).

Personality changes from post-treatment to follow-up

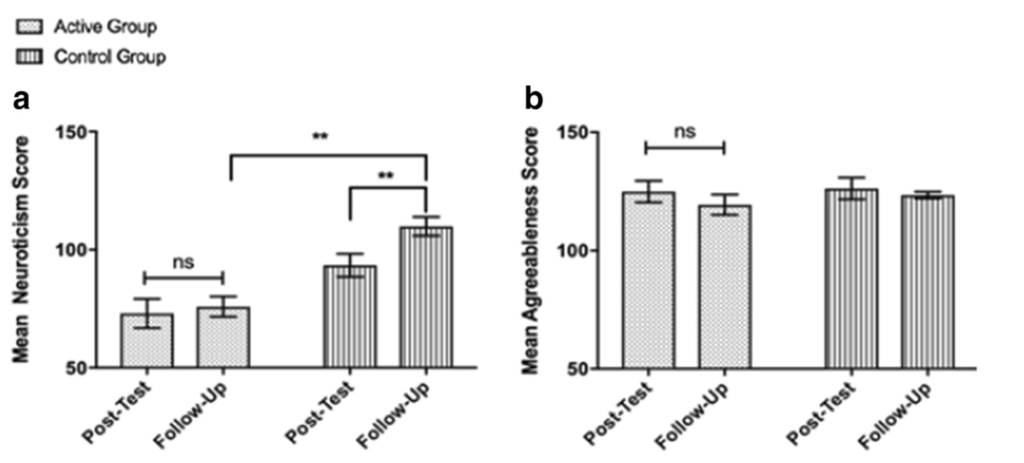

Mixed ANOVA also indicated a significant interaction between time, personality, and group from post-treatment to follow-up. Pairwise comparisons revealed that the reduction in Neuroticism scores observed in the active group at post-test remained stable at the 6-month follow-up assessment (d = 0.08, p = .539), and remained significantly lower than those observed in the comparison group (d = 1.71, p < .001). In addition, the short-term increase in Agreeableness that was observed in the active group was maintained at 6-month follow-up (d = 0.26, p = .151) (Figure 2). Lastly, at 6-month follow- up, significantly greater Openness to experience scores in the active group compared with the comparison group was also observed (d = 2.20 p < .001).

Figure 2

Significant reduction in Neuroticism (a) and increase in Agreeableness scores (b) observed in the active group at post-test remained stable at 6-month follow-up and were significantly reduced in comparison with the comparison group at follow-up. In contrast, we observed a significant increase in Neuroticism scores in the comparison group from post-test to 6-month follow-up. Double asterisk indicates p < .001. Bars represent SEM.

Integration with extant literature

Personality is thought of as stable once the age of maturity is reached at 30 years (Costa Jr & McCrae, 1992). Change is however possible if a significant event occurs, with the usual pathways including adopting a new role in society or vocationally (Hudson et al., 2012; Lodi-Smith & Roberts, 2007), maturation (Bleidorn et al., 2009), psychotherapy (Noordhof et al., 2018), genetics (McCrae et al., 2000), general motivation to change (Allan et al., 2018) and normal development (Roberts et al., 2006). The data presented in this study suggests ayahuasca can result in significant reductions in Neuroticism as well as increases in Agreeableness, and that this change is maintained for at least six-months. Furthermore, the degree of lessening in Neuroticism scores from pre- to post-retreat were associated with higher ratings of mystical experience, as measured by the MEQ. Only trait increases were observed in Openness scores, contrary to the hypotheses. As the average participant age was 37.6, the fact change was witnessed in personality structure is significant. The results however are not directly in line with predictions, primarily based on the findings by MacLean et al. (2011), suggesting Openness would increase. It was predicted that there may be some effect on levels of Neuroticism, yet the results show that the effect was more pronounced than hypothesised.

We investigated further to establish whether the sample group tested had above average levels of Openness prior to ayahuasca sessions, implying a ceiling effect may have restricted increase in this domain. This would make sense, as all participants had chosen to participate in a series of traditional ceremonies in the Amazon, with good knowledge that the structure was based around local spiritual beliefs. Further weight to this notion is added by the fact that it is unlikely that many people would pay the $1750 USD retreat fee without doing background research into the centre itself. It was apparent that the sample group indeed had above average levels of Openness compared to the general population (mean = 129 compared to population average of 124), implying that ayahuasca users in the Amazon rainforest tend to be individuals who score higher in this domain. This, however, was also the case for the control group (mean = 133). Control group participants were backpackers travelling around Peru, therefore fulfilling the criteria of being open to new experience by virtue. Alternatively, it is possible they may have higher levels of Openness because of exercising this trait whilst travelling. In addition, the relatively small sample size could have contributed to the null results in this paper. In hindsight, it would be of benefit to have data points prior to a participant’s departure from home. This would allow the impact of being abroad on personality scores to be assessed. It is plausible that both backpacking (comparison group) and events leading to booking ayahuasca sessions (active) may have raised the individuals Openness scores before initial assessment. This is, however, contrary to previous research that suggests personality is stable once maturity is reached (Costa & McCrae, 1992; Terracciano et al., 2006). To my knowledge, there have been no studies investigating the impact of travelling on personality structure. This is a concept that could be investigated by those with a specific interest in such an area. Unfortunately, testing participants in advance of their ayahuasca retreats is difficult to achieve logistically, however, our current research is attempting to implement this.

Discover the Indigenous Reciprocity Initiative of the Americas

Since publication of this paper, Weiss et al. (2021) have published a similar, larger scale study also investigating personality change in ayahuasca retreat centres following a traditional framework. 256 participants were assessed partaking in ayahuasca retreats in three centres in Central and South America. Participants were evaluated at three time points; baseline, post retreat and three-month follow-up. Similarly, reductions in levels of Neuroticism were found. In addition, increases in Openness, Extraversion, Conscientiousness and Agreeableness were also observed, and all but Conscientiousness was maintained at three-month follow-up. Interestingly, the authors assessed the impact of predisposing factors on personality change. Baseline personality, demographic characteristics, and experiential elements such as altered states of consciousness as well as affect were measured and their ability to moderate personality change assessed. Changes in Neuroticism were found to be moderated by the acute ayahuasca experience, baseline personality scores and the experience of the purge (Weiss et al., 2021).

Expectancy Effects

Expectancy effects have been shown to be influential in psychedelic research (Aday et al., 2021). Weiss et al. (2021) demonstrated that expectancy effects enhanced change in the personality domains Conscientiousness, Extraversion, and Neuroticism in participants consuming ayahuasca in retreat settings. Furthermore, those who had high expectations in terms of preferable decreases in Neuroticism, anxiety, and depression scored higher on baseline measures of Neuroticism and subsequently displayed greater reductions following ayahuasca consumption, both in the short and long term (Weiss et al., 2021). Moreover, those who expected increases in Conscientiousness and Extraversion scored lower in these areas before drinking ayahuasca and demonstrated larger increases following ceremonies and at follow-up. Those who scored higher on suggestibility had higher levels of Neuroticism at baseline, before showing greater reductions in this domain pre – and post retreat. Given the similarities in both setting and participants, it is likely such moderating factors were at play in our study.

The personality characteristic Neuroticism has been found to predict the development of various psychopathologies, including anxiety, depression, and addiction…

Study Relevance

The personality characteristic Neuroticism has been found to predict the development of various psychopathologies, including anxiety, depression, and addiction (Zinbarg et al., 2016), results suggesting Amazonian ayahuasca retreats may have therapeutic potential. However, implementing interventions that decrease levels of Neuroticism also gives rise to theoretical concerns, many of which span into socio-political contexts, the question of what level of neurosis is deemed to be healthy, for instance. It could be argued that neurosis is required for individuals to function in the modern world, which requires organisation and motivation to stick to calendars and schedules. It is possible that excessive reductions in levels of Neuroticism may hinder the ability to function in such regimented societies. This concept requires consideration, especially in conjunction with the growing support for psychedelic-therapy.

References

Aday, J., Heifets, B. D., Pratscher, S. D., Bradley, E., Rosen, R., & Woolley, J. (2021). Great Expectations: Recommendations for improving the methodological rigor of psychedelic clinical trials.

Allan, J., Leeson, P., & Martin, S. (2018). Application of a 10 week coaching program designed to facilitate volitional personality change: Overall effects on personality and the impact of targeting. International Journal of Evidence Based Coaching and Mentoring, 16(1), 80-94.

Barbosa, P. C. R., Cazorla, I. M., Giglio, J. S., & Strassman, R. (2009). A Six-Month Prospective Evaluation of Personality Traits, Psychiatric Symptoms and Quality of Life in Ayahuasca-Naïve Subjects. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 41(3), 205-212. https://doi.org/10.1080/02791072.2009.10400530

Barbosa, P. C. R., Strassman, R. J., da Silveira, D. X., Areco, K., Hoy, R., Pommy, J., Thoma, R., & Bogenschutz, M. (2016). Psychological and neuropsychological assessment of regular hoasca users. Comprehensive psychiatry, 71, 95-105.

Barrett, F. S., Johnson, M. W., & Griffiths, R. R. (2015). Validation of the revised Mystical Experience Questionnaire in experimental sessions with psilocybin. Journal of psychopharmacology, 29(11), 1182-1190.

Benjamini, Y., & Hochberg, Y. (1995). Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal statistical society: series B (Methodological), 57(1), 289-300.

Bleidorn, W., Kandler, C., Riemann, R., Angleitner, A., & Spinath, F. M. (2009). Patterns and sources of adult personality development: Growth curve analyses of the NEO PI-R scales in a longitudinal twin study. Journal of personality and social psychology, 97(1), 142.

Bouso, J. C., González, D., Fondevila, S., Cutchet, M., Fernández, X., Ribeiro Barbosa, P. C., Alcázar-Córcoles, M. Á., Araújo, W. S., Barbanoj, M. J., & Fábregas, J. M. (2012). Personality, psychopathology, life attitudes and neuropsychological performance among ritual users of ayahuasca: a longitudinal study.

Costa Jr, P. T., & McCrae, R. R. (1992). Four ways five factors are basic. Personality and Individual Differences, 13(6), 653-665.

Costa Jr, P. T., & McCrae, R. R. (2008). The Revised Neo Personality Inventory (neo-pi-r). Sage Publications, Inc.

Costa, P. T., & McCrae, R. R. (1992). Normal personality assessment in clinical practice: The NEO Personality Inventory. Psychological assessment, 4(1), 5.

Erritzoe, D., Roseman, L., Nour, M., MacLean, K., Kaelen, M., Nutt, D., & Carhart‐Harris, R. (2018). Effects of psilocybin therapy on personality structure. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 138(5), 368-378.

Grob, C. S. M., Dennis J.Callaway, James C. Brito, Glacus S. Neves, Edison S. Oberlaender, Guilherme. Saide, Oswaldo L. Labigalini, Elizeu. Tacla, Cristiane. Miranda, Claudio T. Strassman, Rick J. Boone, Kyle B. (1996). Human psychopharmacology of hoasca, a plant hallucinogen used in ritual context in Brazil. the Journal of nervous & Mental disease, 184(2), 86-94.

Hudson, N. W., Roberts, B. W., & Lodi-Smith, J. (2012). Personality trait development and social investment in work. Journal of research in personality, 46(3), 334-344.

Kavenská, V., & Simonová, H. (2015). Ayahuasca Tourism: Participants in Shamanic Rituals and their Personality Styles, Motivation, Benefits and Risks [journal article]. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 47(5), 351-359. https://doi.org/10.1080/02791072.2015.1094590

Lodi-Smith, J., & Roberts, B. W. (2007). Social investment and personality: A meta-analysis of the relationship of personality traits to investment in work, family, religion, and volunteerism. Personality and social psychology review, 11(1), 68-86.

MacLean, K. A., Johnson, M. W., & Griffiths, R. R. (2011). Mystical experiences occasioned by the hallucinogen psilocybin lead to increases in the personality domain of openness. Journal of psychopharmacology, 25(11), 1453-1461.

McCrae, R. R., Costa Jr, P. T., Ostendorf, F., Angleitner, A., Hřebíčková, M., Avia, M. D., Sanz, J., Sanchez-Bernardos, M. L., Kusdil, M. E., & Woodfield, R. (2000). Nature over nurture: temperament, personality, and life span development. Journal of personality and social psychology, 78(1), 173.

Noordhof, A., Kamphuis, J. H., Sellbom, M., Eigenhuis, A., & Bagby, R. M. (2018). Change in self-reported personality during major depressive disorder treatment: A reanalysis of treatment studies from a demoralization perspective. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment, 9(1), 93.

Roberts, B. W., Walton, K. E., & Viechtbauer, W. (2006). Patterns of mean-level change in personality traits across the life course: a meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychological bulletin, 132(1), 1.

Terracciano, A., Costa Jr, P. T., & McCrae, R. R. (2006). Personality plasticity after age 30. Personality and social psychology bulletin, 32(8), 999-1009.

Weiss, B., Miller, J. D., Carter, N. T., & Campbell, W. K. (2021). Examining changes in personality following shamanic ceremonial use of ayahuasca. Scientific reports, 11(1), 1-15.

Zinbarg, R. E., Mineka, S., Bobova, L., Craske, M. G., Vrshek-Schallhorn, S., Griffith, J. W., Wolitzky-Taylor, K., Waters, A. M., Sumner, J. A., & Anand, D. (2016). Testing a hierarchical model of neuroticism and its cognitive facets: Latent structure and prospective prediction of first onsets of anxiety and unipolar mood disorders during 3 years in late adolescence. Clinical Psychological Science, 4(5), 805-824.

Art by Mariom Luna.

Take a minute to browse our stock:

Did you enjoy reading this article?

Please support Chacruna's work by donating to us. We are an independent organization and we offer free education and advocacy for psychedelic plant medicines. We are a team of dedicated volunteers!

Can you help Chacruna advance cultural understanding around these substances?