- Broken Spears: The Impact of Colonialism on the Aztec Empire - August 13, 2021

Unfortunately, while psychedelic advocates often refer to the Aztecan use of various plant entheogens, too few understand how the entheogenic Inquisition of the Americas established anti-psychedelic biases and laws that prohibited the possession of sacred plants

This month, humankind will witness the 500th anniversary of the fall of the Aztec Empire. On August 13th, untold millions have reason to reflect upon what was lost five centuries ago in Central Mexico. An entire Indigenous empire was torn asunder by a merciless conquistador named Cortés; the city of Tenochtitlan left in ruins; Motecuhzoma, their leader, murdered amid turmoil within his empire’s capital; priceless treasures of Indigenous Mexican history and culture—all desecrated. Unfortunately, while psychedelic advocates often refer to the Aztecan use of various plant entheogens, too few understand how the entheogenic Inquisition of the Americas established anti-psychedelic biases and laws that prohibited the possession of sacred plants (Sisko, 2021).

Recordings are now available to watch here

Modern Perspectives

In this modern age, society rarely reflects upon the deep impact that colonialism has left on society. In Mexico, schoolchildren are taught how the eagle centered on their flag is based upon the Aztec “Leyend.” Seven centuries ago, the Mexica people wandered the subcontinent looking for a place to call home while awaiting a sign from their patron deity, Huitzilopochtli. While exploring Lake Texcoco, the Mexica people witnessed an eagle grasping a serpent while perched atop a prickly pear cactus. Embedded within the center of the Mexican flag, this symbol serves to remind others of the true history of Mexico: one that is often forgotten.

To move forward in this modern conundrum, everyone must dedicate some time to learn about the history of the Americas. To this end, it would be appropriate to echo the words of President Kennedy. JFK deserves enormous credit for drawing attention to the injustices cast upon Indigenous Americans. Amid the heated election of 1960, Kennedy famously pledged he would fulfill a “moral obligation to our first Americans” by ending the “Indian Termination Policy,” a governmental policy that sought to strip Native people of their legal protections.

Aware of the rich histories of these people, Kennedy once wrote that, if we wish to “set out on the road to success,” we must begin by learning about Native American history: “Only through this study can we as a nation do what must be done if our treatment of the American Indian is not to be marked down for all time as a national disgrace.” (Kennedy & Brandon, 1960).

Cortés the Killer

Years before Indigenous Mexicans knew the terror of genocide, Hernán Cortés sailed from Cuba to the east coast of Mexico with over 500 soldiers and seamen willing to do his bidding (Riding, 2001). In an open act of treason, Cortés defied the Governor of Cuba, stole ships, and sailed to Mexico seeking gold, land, slaves, and eternal glory.

While at San Juan de Ulúa on Easter Sunday of 1519, Cortés was greeted by the Aztec governors Pitalpitoque and Tentlil, alongside many well-dressed Indigenous Mexicans bearing golden tributes, precious stones, and plentiful food supplies. As a show of power, the two governors had been dispatched by Motecuhzoma Xocoyotzin, the deified tlahtoāni (king) who ruled the city-state of Tenochtitlan.

Despite the warm welcome, Cortés allegedly claimed that gold “is good for a bad heart” and that his compadres “suffer from a disease of the heart which can only be assuaged with gold” (Riding, 2001). This disease of the heart, I speculate, was unparalleled malice.

Marching west, the renegade conquistador began a ruthless campaign to gain control of Mexico at any cost. Aware that his mutinous acts invited scrutiny, Cortés expedited golden treasures and flattering letters to the Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V. Painting himself as a merciful hero, Cortés wrote these letters so Europe may know “the truth of all that has happened” on the distant continent (Cortés & MacNutt, 1908).

At one point, 50 Tlaxcalan warriors were found spying on the Spaniards; in retaliation, Cortes ordered his men to amputate the Tlaxcalan warriors’ hands before they were returned to Xicotencatl, their leader.

Though these letters are riddled with exaggerations, blatant omissions, and outright lies, there’s a disturbing fact hidden within their subtext. Deprived of reason by his own narcissism, Cortés took pride and satisfaction in his brutality. In his second letter, Cortés felt no shame in admitting that he “slaughtered many” innocent Natives during his westward expedition; women and children were afforded no quarter. At one point, 50 Tlaxcalan warriors were found spying on the Spaniards; in retaliation, Cortes ordered his men to amputate the Tlaxcalan warriors’ hands before they were returned to Xicotencatl, their leader. Cortés informed King Charles that this was done so that Xicotencatl “would see who we are.”

The renegade Spaniard was pleased to tell King Charles that Xicotencatl and his people “promis[ed] they would serve Your Majesty very loyally.” The independent city-state of Tlaxcala reluctantly formed a military alliance with Cortés, simply to ensure that their people would not disappear from history.

With his eyes set on Tenochtitlan, Cortés and his troupe of marauders mounted steeds and struck terror into every village they razed and plundered. Armed with cannons, crossbows, and arquebuses, Cortés eventually amassed untold thousands of Indigenous warriors willing to do his bidding.

Cortés Reaches Tenochtitlan

By early November of 1519, Cortés had reached the glorious metropolis of the Aztec Empire. Larger than most European capitals, Tenochtitlan was an island-city near the western banks of Lake Texcoco. Populated by hundreds of thousands of Aztec citizens and connected by immense causeways, the enchanting city featured a thriving marketplace, temples, zoos, aquariums, and even a botanical garden. Taking in all of the splendors, Cortés enthused in his third letter that Tenochtitlan was “the most beautiful thing in the world.”

Depicting Motecuhzoma as a weak leader, Cortés wrote in his second letter that the tlahtoāni openly expressed his subservience, saying, “you will be obeyed and recognized” and that “all we possess is at your disposal.” Though Motecuhzoma likely gave Cortés lavish golden presents as a show of strength, Motecuhzoma exposed the riches of the Aztec people; an act which only whetted the appetites of the conquistadors.

In an effort to gain control of the city-state, Cortés coerced Motecuhzoma into docility under the threat of murder. Over several months, Motecuhzoma was held as prisoner, yet continued to run the Aztec Empire while Cortés carefully planned to conquer the whole of Mexico.

By spring, Cortés faced an overdue reckoning. Pánfilo de Narváez had arrived on the eastern coast of Mexico with orders to capture Cortés. The renegade conquistador departed the Aztec capital with his most valuable soldiers. Though Cortés was highly outnumbered, in a surprising twist of fate, he emerged victorious and even persuaded Pánfilo’s troops to join him. These soldiers would soon come to regret their choice.

Discover the Indigenous Reciprocity Initiative of the Americas

Horror at the Great Temple

When everyone was enjoying the celebration, … they came into the patio, armed for battle. They came to close the exits [and] no one could get out anywhere. …They cut off the heads of some and smashed the heads of others into little pieces … Some tried to escape, but the Spaniards murdered them at the gates while they laughed.

While Cortés was away, the island-city celebrated the Festival of Toxcatl. As the ceremonies began within the Sacred Patio of the Great Temple, the conquistadors coveted the golden jewelry adorning the festival-goers. While people were dancing, the Spaniards drew their swords. One native of Tenochtitlan gave the following account:

When everyone was enjoying the celebration,… they came into the patio, armed for battle. They came to close the exits [and] no one could get out anywhere. …They cut off the heads of some and smashed the heads of others into little pieces … Some tried to escape, but the Spaniards murdered them at the gates while they laughed. (León-Portilla, 1962)

After they slaughtered innumerable members of Aztec nobility, the Spaniards stole golden jewelry from the slain bodies, escaped, and barricaded themselves in Axayacatl’s palace with Motecuhzoma as a hostage. Laying siege, the Aztecs sought revenge for the senseless massacre. Hurrying back into Tenochtitlan, Cortés made his way into the palace and ordered Motecuhzoma to address the grieving city. Here’s where the story is unclear: the Spaniards claim Motecuhzoma was stoned to death, yet Aztec accounts assert that Cortés murdered Motecuhzoma. Most historians are inclined to believe the latter.

The Night of Sorrows

Well aware that he lost control of Tenochtitlan, Cortés faced a grim situation: The island city was surrounded for miles by enemy territory. Under the cover of a crescent moon and a rainstorm, Cortés and his men gathered their swords and stolen gold before attempting to escape unnoticed. When they tried to cross the western causeway, night-watchmen sounded the alarm, the Spaniards ran for their lives, and Aztec warriors hunted them from behind. Because of their dire need to survive, the starving marauders lost their cannons, horses, and hundreds of troops. Many drowned in Lake Texcoco simply because they were weighed down by heavy armor and stolen gold. Though Cortés openly wept after he realized “all the gold” had been lost (Cortés & MacNutt, 1908), he quickly began plotting his revenge.

The Revenge of Cortés

Shy of a year after his bitter defeat, Cortés returned to the shores of Lake Texcoco with tens of thousands of Indigenous warriors. Though it’s true that Cortés subjugated “innumerable multitudes” of Indigenous Mexicans to fight for him (Clavigero, 2012), these same people despised how Motecuhzoma coerced auxiliary provinces into providing tributes for the Aztec Empire. Well aware that he pitted Indigenous Mexicans against each other to his advantage, Cortés ordered his troops to lay siege upon Tenochtitlan.

Beginning in late May of 1521, Cortés mounted a merciless 80-day attack on the island-city by destroying all of their fresh-water aqueducts, cutting off the city’s causeways to halt incoming supplies, and even killing those fishing on the salt-water lake to feed their families. Supported by wooden brigantines positioned within the lake, Cortés attacked the Aztec soldiers on the causeways.

Recently struck by an epidemic of smallpox, the Aztec warriors fought to the death to defend their nation. Suffering from famine and overwhelming numbers of enemy troops, the Aztec empire finally fell on August 13, 1521. Starving Aztec families would beg the Spaniards for mercy while thousands of lifeless bodies floated nearby on Lake Texcoco.

The first surviving Aztecan poem of the fall of Tenochtitlan, “Broken Spears,” was written by an unknown scribe (León-Portilla, 1962). Though it utilized the Spanish alphabet, the author likely wrote the piece in Nahuatl to preserve their story.

“Broken spears lie in the roads;

we have torn our hair in our grief. …

We have pounded our heads in despair against the adobe walls,

for our inheritance, our city, is lost and dead.”

“Broken spears lie in the roads;

we have torn our hair in our grief. …

We have pounded our heads in despair against the adobe walls,

for our inheritance, our city, is lost and dead.”

Final Words

As August 13th approaches this year, I hope each of us takes time to consider how colonialism’s impact continues to shape our present moment in history. If we wish to correct the errors of the past, we must learn, as Cortés once said, “the truth of all that has happened.”

The question remains: What is the truth of all that transpired in Mexico? Because Spanish missionaries burned nearly every codex written by Indigenous scribes (Sisko, 2021), we’ll unfortunately never fully know.

Thankfully though, voices within the psychedelic community (esp. Chacruna Institute) are gathering to raise awareness about this dark period of history. With enough time, humankind will come to appreciate the beauty and vibrancy of Aztec culture.

Art by Mariom Luna.

References

Clavigero, F., & Cullen, C. (1806). The history of Mexico: Collected from Spanish and Mexican historians, from manuscripts and ancient paintings of the Indians. Illustrated by charts and other copper plates. To which are added, critical dissertations on the land, the animals, and inhabitants of Mexico. Richmond, VA: William Prichard.

Cortés, H., & MacNutt, F. A. (1908). Letters of Cortés: Five letters of relation to the Emperor Charles V. New York City, NY: Putnam.

Kennedy, J. F., & Brandon, W. (1960). Introduction. In A. M. Josephy (Ed.), American Heritage book of Indians. Rockville, MD: American Heritage.

León-Portilla, M. (1962). The broken spears: The Aztec account of the conquest of Mexico (L. Kemp, Trans.). Boston, MA: Beacon.

Leutze, E. (1848). Storming of the Teocalli by Cortez and his troops [Oil on canvas]. Wadsworth Artheneum, Hartford, CT.

Riding, A. (2001, May 6). TELEVISION/RADIO; a conquest whose daring matched its cruelty. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2001/05/06/arts/television-radio-a-conquest-whose-daring-matched-its-cruelty.html

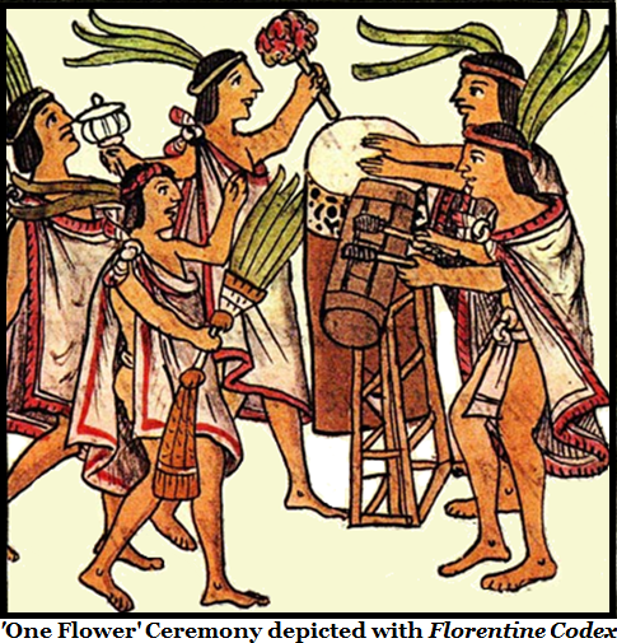

Sahagún, F. B. de (1950). General history of the things of New Spain: Florentine codex. Santa Fe, NM: The School of American Research

Sisko, S. T. (2021). The entheogenic inquisition: Persecution in Mexico. Unpublished manuscript submitted to Chacruna Institute.

Take a minute to browse our stock:

Did you enjoy reading this article?

Please support Chacruna's work by donating to us. We are an independent organization and we offer free education and advocacy for psychedelic plant medicines. We are a team of dedicated volunteers!

Can you help Chacruna advance cultural understanding around these substances?