- Agony and Ecstasy in the Amazon: Tobacco and the hummingbird shamans of Peru - January 27, 2022

- Toé (Brugmansia suaveolens): The Path of Day and Night - June 2, 2020

- Fifty Shades of Green - May 27, 2020

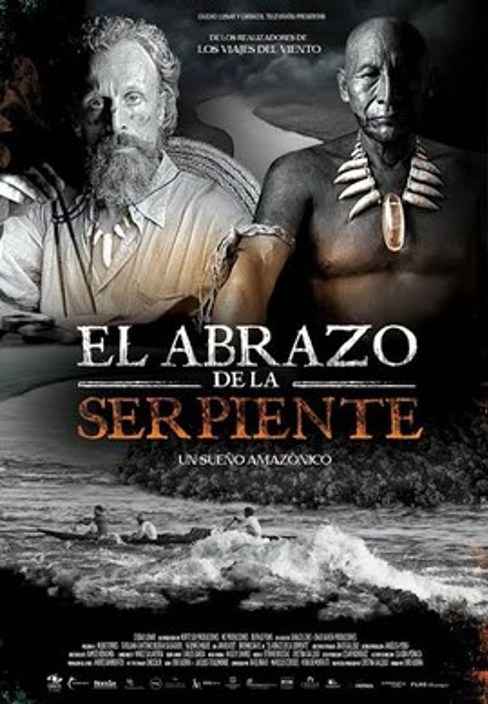

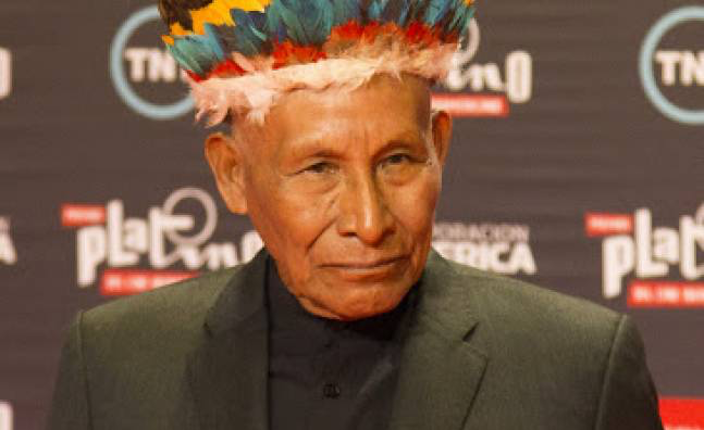

The tragic death from coronavirus of indigenous actor Antonio Bolivar, star of the Oscar-nominated film Embrace of the Serpent, has made me reflect back on all the facts the film got wrong and the truths it got right.

Within the first few seconds, my already high expectations of ethnographic authenticity were already surpassed.

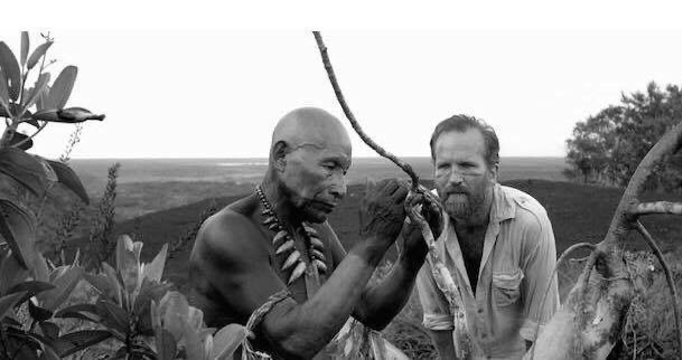

As the lights in the cinema went down and the opening scene of Ciro Guerra’s 2015 film, The Embrace of the Serpent, began to flicker on the screen, I was primed to be blown away. The film, based loosely on the field experiences of legendary Amazon explorers Theodor Koch-Grünberg and Richard Schultes, and shot on location in the Colombian Amazon with indigenous actors, was being hailed as visionary. Within the first few seconds, my already high expectations of ethnographic authenticity were already surpassed. In the opening sequence, the protagonist, Karamakate, whose youthful self is played by Cubeo indigenous actor Nibio Torres, brandishes a long, slender spear that buzzes like a rattlesnake when shaken. As a researcher and museum curator who has worked in adjacent regions of the northwest Brazilian Amazon, I have seen identical ceremonial rattle-spears in ethnographic collections and heard them deployed in rituals.

“Sssssss,” began the hissing sound, not of a serpent but of my rapidly deflating enchantment.

Cinematic representations of the Amazon have a long and dismal history of exoticism, sensationalism, and pure fantasy; from The Emerald Forest to Medicine Man to Anaconda. At last, a popular feature film that represents Amazonian peoples accurately! And yet, instants later, these admittedly high hopes were dashed. When the canoe containing the German explorer “Theo” (Koch-Grünberg’s pseudonym in the movie) gets closer to the bank, Karamakate pops off the spear’s rattle-tip to reveal a blowgun that he aims menacingly at the intruder. Though indigenous peoples of the Vaupes region indeed use blowguns with curare-tipped darts for hunting, I am not aware of any culture that combines these two pieces of material into a single, interchangeable, multipurpose weapon. “Sssssss,” began the hissing sound, not of a serpent but of my rapidly deflating enchantment.

The good-natured laughter of villagers at the antics of curious Theo invoked for me an embarrassed déjà vu of some of my own early field experiences.

This was, of course, a petty quibble over a minor ethnographic detail. Embrace of the Serpent is certainly the most culturally detailed and narratively sympathetic depiction of indigenous Amazonian peoples in a major feature production since Hector Bebenco’s 1991 At Play in the Fields of the Lord. The first Colombian feature ever nominated for an Oscar, the film has brought international attention to the cultures, languages, and historical suffering of indigenous peoples at the hands of colonialist outsiders. The lush, on-location photography on 35 mm black- and-white film, a cumbersome choice in the days of digital studio convenience, gives the film an epic quality that accurately captures the enduring aesthetic of documentary photographs by Koch-Grünberg and Schultes. Some of the most beautiful scenes in the film depict the peaceful rhythm and subtle humor of life in indigenous villages: The good-natured laughter of villagers at the antics of curious Theo invoked for me an embarrassed déjà vu of some of my own early field experiences.

And yet, the repeated alternation between such intense scenic and ethnographic accuracy, with whole-cloth fabrications like the pop-off rattle spear/blowgun, began to provoke me beyond mere irritation over petty details towards a deeper sense of unease with the misleading stereotypes the film nonetheless transmits. Symptomatic of this broader problem was a 2016 interview, during which filmmaker Cirio Guerra claims, “Amazonian people have fifty words for what we call green.” The statement is even more of a whopper than the infamous anthropological myth about the “hundred Eskimo words for snow,” which at least harkened back to Franz Boas’s passing mention of four (not 100) terms for snow in Eskimo-Aleut.1 In Guerra’s case, there is not even the pretense of any underlying scholarly claim.

If anything, the opposite is true, since many indigenous languages of the Americas combine the concepts of green and blue into a single term. The Amazonian language I know best, spoken by the Matsigenka people (protagonists of another hallucinatory Amazonian feature film, Fitzcarraldo by Werner Herzog), has no unique color term for green. To describe the color of living or freshly picked leaves, the Matsigenka say kaniari, which means “raw” or “fresh,” also used to describe uncooked meat or fish.2 The linguistic logic would appear to be that, with so much foliage in the environment, there is no need for any special word for green, since it is everywhere; unique color terms are used only to describe “purple-blue” (kamochongari) variations in natural leaf color or the “yellow” (kiteri) color of wilting leaves.

This is, of course, a feature film, and the film maker is permitted poetic license. As Robin Wright wrote in Chacruna, soon after the film’s release: “One can, perhaps, forgive the distortions of the historical record in Ciro Guerra’s film. It is art… after all.” However, in films that go to such great pains to reproduce indigenous languages and cultures in such precise detail, poetic license can become irresponsible, even dangerous, when it results in the audience confusing fiction with fact. I call this the “Apolcalypto Effect,” after the 2006 Mel Gibson fiasco that so badly mangled classic Mayan costume and architecture from the first millennium A.D. with Aztec human sacrifice eight centuries years later that uninformed relatives of mine came away from the film remarking on what a blessing it was the Spanish arrived to stop all that carnage. In an imaginative film like Avatar, there is no question of factual authenticity; but a work that hews so closely to the aesthetics and cultural details of actual indigenous peoples should be more careful about disseminating false (as opposed to merely poetically fanciful) narratives.

Ciro Guerra justified his mashup of the actual psychoactive shamanic plants yekoana (Virola theiodora) and chacruna (Psychotria viridis) into the fictional yakruna (which resembles an orchid flower on a Brugmansia shrub) as a gesture to safeguard indigenous knowledge. But worse than this botanical Babel was the repetition of the same hackneyed motif from one particularly awful ethnobotanical film, the 1992 Sean Connery adventure, Medicine Man, where the miracle cancer cure is isolated from a vanishingly rare ant species residing in a single tree slated for felling by loggers. Despite the narrative appeal of this trope, medicinal and other useful species employed by indigenous societies tend to be rather common,3 since rare plants are, by definition, difficult to locate, use, and share with any degree of reliability.

But, of course, taking away the fictional, final yakruna plant’s singularity would rob the film of the clichéd quest to find “The Last Specimen of The Sacred Plant”—conveniently located near a photogenic mountain—that, in turn, reinforces the film’s larger cliché about “The Last Shaman of the Tribe who Still Maintains The Old Ways.” As anthropologist Eduardo Viveiros de Castro pointed out soon after the film’s release, “living completely alone is part of this fiction, because the indigenous logic is completely different from ours, and it would be very difficult for someone to maintain traditional customs in isolation from others.” Worse still, Embrace of the Serpent, much like Medicine Man, ends with the native protagonist, in this case, the elder version of Karamakate, played by indigenous actor Antonio Bolivar, handing over the mantle of his shamanic knowledge—indeed the very last flower of the last specimen of yakruna in existence—to the white scientist “Evan” (based on ethnobotanist Richard Evans Schultes), since his own people have lost their way.

It is not lone shamans leading solitary lives in the forest who keep indigenous languages, cultures, and religion alive; much less, white scientists or gringo apprentices.

As appealing as such a quest motif is to moviegoers, it disrespects the true history of resistance and resilience of indigenous societies in the Amazon and beyond. It is not lone shamans leading solitary lives in the forest who keep indigenous languages, cultures, and religion alive; much less, white scientists or gringo apprentices. Indigenous communities, federations, political and philosophical leaders, and a growing cadre of university-educated intellectuals continue to do the hard and often dangerous work of defending their lands, languages, and ways of life against an ongoing, centuries-long assault by outside economic, political, and missionary interests.

Thus, it is doubly ironic, given the deprecating treatment of its two scientist-protagonists, that the film’s epigraph claims that only the photographs and writings of these hapless adventurers have preserved the culture of these extinct peoples.

Embrace of the Serpent does injustice to the scientific legacies of both Koch Grunberg and Richard Schultes, but I care less about these slights than the stereotypical depiction of indigenous peoples as having “lost their culture.” Indigenous peoples of the Vaupes region in Colombia and neighboring areas of Brazil are engaged in a historic process of cultural revival, and Amazonian cultures more generally have showed remarkable resilience and adaptability. Thus, it is doubly ironic, given the deprecating treatment of its two scientist-protagonists, that the film’s epigraph claims that only the photographs and writings of these hapless adventurers have preserved the culture of these extinct peoples. The explicit reiteration of this cliché, both inane and untrue, just before the end credits, put the nail in the coffin on my opinion of the film at that time. Given the wild enthusiasm of everyone else around me, I hoped to temper my disappointment with a second viewing a few days later. And yet, like in the Seinfeld episode about The English Patient, nothing could relieve my deeply negative feelings about the film, to the point where I, like Elaine in Seinfeld, became frustrated, impatient and even aggressive with everyone else’s wide-eyed rhapsodizing.

I intended to write up these thoughts at the time, but had to undergo surgery for a life-threatening case of appendicitis that had gone undiagnosed during many months on dangerously remote fieldwork trips. So, I allowed this review, and many other academic and writing responsibilities, to lapse during my slow convalescence. By the time I had recovered and caught up, the moment had passed.

The deadly pandemic coincides with a disturbing resurgence of invasion and violence against indigenous people, driven by the same economic, political, and religious forces depicted so powerfully in the film.

But now, upon learning of the death last week to coronavirus of Antonio Bolivar, the actor who played the elder version of Karamakate in the film, I am perhaps relieved that I did not share these overly negative opinions at the time, only to regret them in the current, catastrophic moment. Coronavirus is spreading rapidly among indigenous populations of the Columbian, Peruvian, and Brazilian Amazon, where local medical infrastructure has proven to be calamitously ill-prepared. The deadly pandemic coincides with a disturbing resurgence of invasion and violence against indigenous people, driven by the same economic, political, and religious forces depicted so powerfully in the film.

By going back and forth between the story of the younger Karamakate trying to heal Theo in the early 1900s, and the elder Karamakate accompanying ethnobotanist Evan in his quest for yakruna (and rubber) in the 1940s, the film draws attention to an unrelenting cycle of physical and cultural violence wrought on indigenous peoples by rubber tappers and Christian missionaries. As Maria Chiara D’Argenio4 writes, although the film’s stereotypes about indigenous people are “not unproblematic,” the film nonetheless “succeeds in foregrounding Indigenous points of view” and “subverting the power relations in colonialist ethnography.” Phantasmagoric scenes set 40 years apart in the jungle town of La Chorrera, the historical epicenter of the Rubber Boom terror on the Putumayo river in Colombia, depict the cruelty of succeeding generations of Christian missionaries and rubber barons. A particularly powerful scene in the film shows a mutilated, handless man desperately trying to recover spilt latex in a rubber tree grove next to a cemetery of native graves, inspired by the real atrocities committed against indigenous people by rubber tapping tycoons. Clearly drawing inspiration from Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness and Francis Ford Coppola’s film Apocalypse Now, these scenes sacrifice any pretense of historical accuracy to depict the horrors of colonialism on a mythic scale.

The death of Antonio Bolivar to the coronavirus pandemic brings into stark relief this central theme of the film that I overlooked in my initial response, so focused on issues of ethnographic and historical accuracy. “Don Antonio,” as he was known in his home town of Leticia, had worked as an actor on previous films about the Amazon, but was reluctant to speak about these productions because he felt they did not respect his culture. However, he praised Embrace of the Serpent as “a film about the Amazon, the lungs of the world, the greatest purifying filter for contaminated air, this is the true wealth of indigenous people.” In a 2016 interview, Bolivar warned, “If people leave Mother Nature alone, if they stop messing with these riches, the problems in the world will calm down. If not, then, logically, there will be a great cataclysm, this Earth will split into two or three pieces, or disappear altogether, who knows?”

Bolivar, who played the lone elder shaman Karamakate, is indeed one of the last surviving members of the Ocaina people, whose language is spoken by only a dozen people in Colombia and some fifty more in Peru. The film includes a disorienting Babel of European languages, including German, Spanish, Portuguese, and Catalan, but gives special prominence to six different indigenous languages, including his critically endangered native tongue, Ocaina. Bolivar helped translate the film’s script into multiple indigenous languages, and local representatives in Colombia have hailed his contribution: “He made us very visible, through the film, nationally and internationally. He showed what the Colombian Amazon really was.”

In the final scene, old Karamakate has vanished, ascending to the spirit world in rejuvenated form, leaving the distraught Evan to contemplate his yakruna visions alone. Discussing the symbolism of the film’s title, Bolivar explained, “Since I am an elder, I have to give my power and wisdom to someone younger, so I thank him and embrace him and, when I die, he stays with my power and wisdom.” It is with great sadness that I received the news of Antonio Bolivar’s death. And yet, his power and wisdom endure in this final performance as the lone elder shaman Karamakate in Embrace of the Serpent.

Art by Mariom Luna.

References

- Boas, F. (1911). Introduction. In F. Boas (Ed.), Handbook of American Indian languages, vol. 1. Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin No. 40 (pp. 25–26). Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution. ↩

- Johnson, A.W., Johnson, O., & Baksh, M. (1986). The colors of emotions in Machiguenga. American Anthropologist, 88, 674–681. ↩

- Stepp, J. R., & Moerman, D. E. (2001). The importance of weeds in ethnopharmacology. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 75(1), 19–23. ↩

- D’Argenio, M. C. (2018). Decolonial encounters in Ciro Guerra’s El Abrazo de La Serpiente: Indigeneity, coevalness and intercultural dialogue. Postcolonial Studies, 21(2), 131–153. ↩

Take a minute to browse our stock:

Did you enjoy reading this article?

Please support Chacruna's work by donating to us. We are an independent organization and we offer free education and advocacy for psychedelic plant medicines. We are a team of dedicated volunteers!

Can you help Chacruna advance cultural understanding around these substances?