- Agony and Ecstasy in the Amazon: Tobacco and the hummingbird shamans of Peru - January 27, 2022

- Toé (Brugmansia suaveolens): The Path of Day and Night - June 2, 2020

- Fifty Shades of Green - May 27, 2020

And, ah, to think how thin the veil that lies

– George William Russell, “Janus”

Between the pain of hell and paradise!

Never tell a Matsigenka shaman his tobacco snuff is anything but katsi, “extremely painful.”

I learned this lesson the way I learned most of my lessons during ethnographic fieldwork and in life generally — the hard way. Many years ago, in a village at the headwaters of the Manú River in the Peruvian Amazon, my friend Shumarapage initiated me into the pungent delights of seri, a fine green powder of tobacco and ash that Matsigenka men blast up one another’s nostrils to dispel fatigue, treat colds, build bonds of friendship, share shamanic powers, or just get plain smashed.

That first time, Shumarapage punished me with an intentional overdose. “Just one more puff,” he kept saying, until ten hits later I was lying in a puddle of green snot and vomit while a crowd of men, raucous on manioc beer, laughed all around me (the Matsigenka have a rather harsh sense of humor).

Among the Matsigenka, such an episode is nothing to be ashamed of: on the contrary, guests are expected to overindulge as a sign of appreciation. And so despite this traumatic initiation, I soon came to savor the sharp sting of tobacco, crave the euphoric rush of nicotine, even appreciate the purifying bouts of retching that sometimes follow a binge.

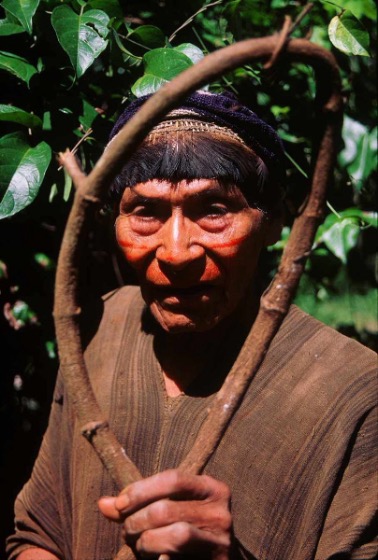

Matsigenka men usually share tobacco at dusk, as the cooking fires begin to flicker against the black wall of the surrounding forest and cicadas, frogs, and nocturnal birds tune up for an all-night symphony. A pair of men, usually brothers-in-law or other close kinsmen, sit facing one another on a dingy cane mat in the sandy plaza between thatched houses where women cook, gossip, nurture young ones, and laugh while children sleep or play. (Women rarely participate in snuff sharing these days.)

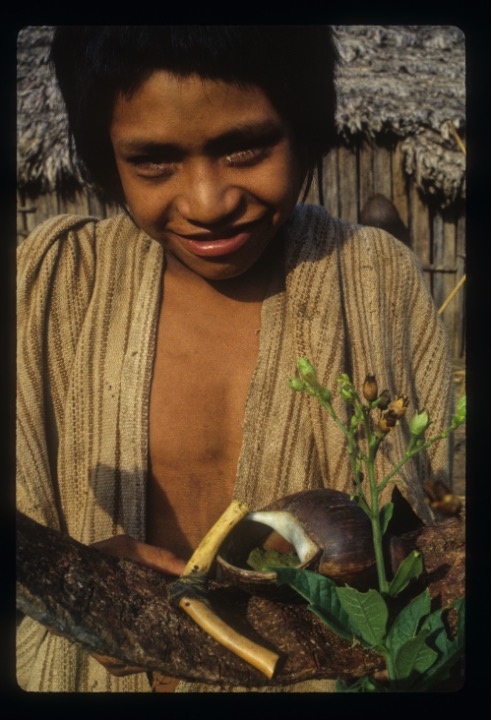

The men are often grimy and tired, having just arrived from their slash-and-burn gardens or a hunting foray. They may chat softly for a few minutes about the day’s toils and revelations — peccaries plundering the manioc crop, tapir tracks along the stream — or they may be too tired, and so remain silent. One of them reaches into a coarsely woven net bag slung across his chest and removes a giant snail shell, known as a pompori in Matsigenka, as white and polished as porcelain from years of use. He extracts a cloth wad from the shell’s orifice, careful not to spill any of the precious green powder stored inside. He raps the shell with his knuckles, tilting it slightly downward so the powder sifts from the coiled innards towards the shell’s mouth.

The tobacco’s owner brandishes his seritonki, or “tobacco bone,” an L-shaped tube made from two leg bones of the curassow, a terrestrial, pheasant-sized game bird with silky black feathers and a hooked, bright red beak. The bones are secured with sticky brown resin and twists of hand-spun cotton. Then follows a brief but animated conversation as the two men decide who will go first — which is to say, who will start out on the receiving end of the seritonki.

“You first!” says the tobacco’s owner.

“No, you first!” says the other man. “Your tobacco is very painful! I’ll never get used to it.”

“You first!” insists the tobacco’s owner.

It’s like watching two gentlemen bicker over who will hold the door.

“All right, I’ll go ahead, but just two nostrils’ full,” the second man acquiesces. He rubs his nose and scratches his head in anticipation.

The man holding the shell dips the barrel of the tobacco bone — fine hatchmarks or circular striations distinguish the nostril side from the smooth end used for blowing — into the powder several times, scraping up a sizable dose. Then he taps the far end of the bone on the rim of the shell, first one side, then backhand on the opposite rim. The shell rings like a silver bell: Ting-ting-ting-ting! Ting-ting-ting!

The staccato ringing of bone on shell is the audial hallmark of the tobacco session, a sound with Pavlovian powers to evoke a craving not so much for the substance alone as for the whole ritualized encounter surrounding its consumption. Some men ring the shell with virtuosic intensity, announcing to all within earshot that tobacco is to be had; but the tapping has a practical function too, making the snuff settle into the juncture where the two bones are bonded.

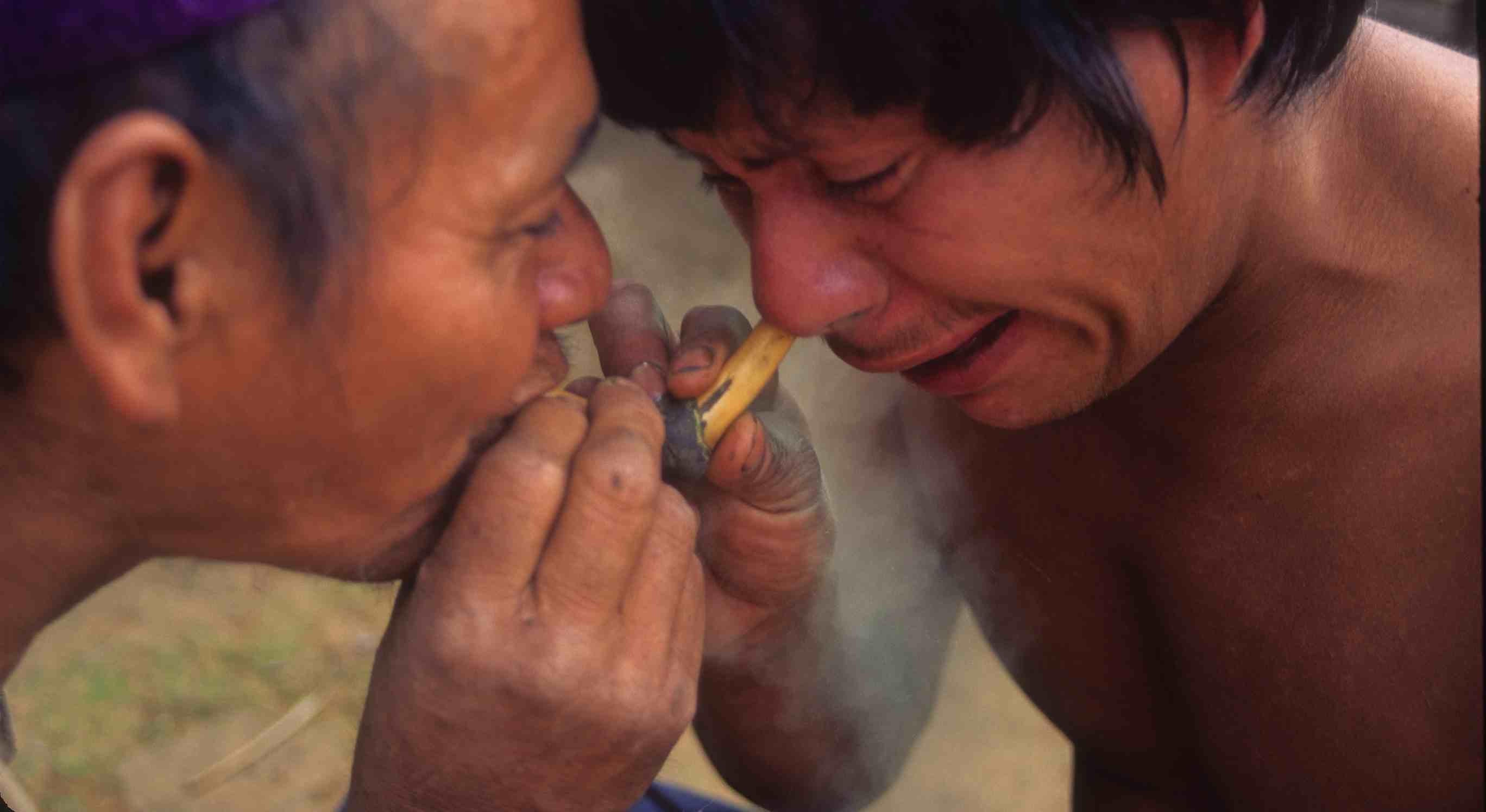

The one holding the loaded tobacco bone leans forward, bringing the striated barrel close to his companion’s face. The man about to receive tobacco closes his eyes tightly, scrunches up his nose, holds his breath, and guides the marked tip of the bone into one nostril. The first man then puckers his lips and puffs on the unmarked end in short blasts to blow the dose of snuff first into one of his friend’s nostrils, then the next, back and forth in quick succession, as his companion tilts his head slightly from side to side to receive the tobacco.

As with shell tapping, each man has his own distinctive style for delivering and receiving the snuff: Some men exhale forcefully in short grunts, while others blow long solid blasts and others still, gentle puffs. Some recipients take a few hits in one nostril before switching, while others go back and forth quickly, and some pause to squint deliberately between nostrils-full. Some tilt, some grimace, some nod, some sway. The giver continues puffing back and forth between nostrils until he is out of breath and satisfied that all remnants of snuff in the tube are buried deep in the sinuses of his companion.

When the first dose (what the Matsigenka call a single “nostril-full” — panakitero — though it is in fact several) is complete, the recipient recoils from the tobacco bone — sometimes grimacing and hacking, sometimes sneezing and rubbing his head, sometimes wiping away tears and crying out as the nicotine burns and stings its way into his mucous membranes. And yet despite the pain, rarely if ever does he pull away after the promised “two nostrils’ full”: Matsigenka etiquette is full of subtle demurring, self-deprecation, and understatement.

They repeat the cycle again and again, scooping snuff, ringing bone on shell, blasting tobacco, until the recipient finally whimpers, “Intaga!” Enough. And then the two switch roles, as the man holding the tobacco bone turns the barrel on himself and packs doses of snuff for the other man to blow up his nose in return.

Soon both are nearly prostrate in nicotine intoxication, with watery eyes, slack faces, sweaty palms, a staggering gait (if they’re even able to walk), and nostrils running copiously with bright green, snuff-laden mucus.

It is not a pretty sight. But to be in that state — to have felt the giddy anticipation, heard the enticing ring of the bone, received the intimate forceful blasts, felt the burning — and to lie reeling afterwards from the short-lived rush — is indescribable: euphoric, transcendent, divine. Best of all, when the brief prostration passes, the user rises with a refreshing lightness and nimbleness of body and mind, utterly free of exhaustion and frustration from whatever toils have preceded. This, I guess, is the reason Matsigenka men so diligently return to their pompori shells night after night: to sweep away the fatigue of their hard, physical lives.

After my own painful initiation — and after learning to judge my tolerance and (mostly) avoid unpleasant overdoses — I too came to crave tobacco snuff as a way of sweeping away mental and physical fatigue after long, hot, scratchy days of pressing plants, hauling supplies, trekking with hunters, taping interviews, and swatting gnats.

But Matsigenka men do not take the sharing of tobacco lightly. A man’s tobacco is a concrete manifestation of his spiritual powers, and sharing tobacco implies the sharing or transfer of these powers. Indeed, the word for shaman in the Matsigenka language is seripigari, literally, “the one intoxicated by tobacco.” The Matsigenka are circumspect to the point of self-deprecation regarding such matters: no self-respecting shaman would ever openly claim to be one. Instead, those who boast of their shamanic powers are tacitly assumed to be sorcerers, who use spiritual powers for selfish, evil ends. The most powerful shamans (like the best hunters) are usually the ones who most vehemently deny any such prowess: The Matsigenka universe is a delicate tapestry of reticence, nuance, and insinuation. And yet anyone who regularly consumes tobacco and other psychoactive plants — especially ayahuasca, a drink I’ll describe later — is, by definition, a shaman, since nicotine intoxication is synonymous with shamanic trance.

Shamanism, it would seem, is a matter of degree rather than kind, and although none but the most insecure or inept would openly admit as much, all those involved in sharing tobacco and ayahuasca are scaling the rungs of shamanic initiation. Not even the sky is the limit: The greatest shamans ascend beyond the heavens to mingle with immortal spirit beings, the very gods of creation who defend and perpetuate the universe through their ceaseless war against the forces of chaos and evil.

As a material substance that stores and transmits spiritual power, tobacco is the shaman’s soul. And the more “painful” or “pungent” (katsi) the tobacco, the more powerful the shaman. Nicotine addiction, a physiological reality, also has a spiritual component: The Matsigenka say a man’s shamanic spirit guide craves tobacco the way a hummingbird craves nectar.

Thus my initiation into tobacco snuff was also an initiation into the profound and subtle realm of shamanism. I went, so the jargon goes, from being a participant observer to being an observing participant. I was soon invited on a regular basis to partake of tobacco snuff, at least with some men. I eventually acquired my own complete tobacco kit — pompori shell, tobacco bone, and net bag (tsagi), to which I added a coiled wad of toilet paper for more civilized disposal of the inevitable green mucus. I have even become a connoisseur of the subtle and intriguing variations between different men’s batches of snuff.

A man’s tobacco is a concrete manifestation of his spiritual powers, and sharing tobacco implies the sharing or transfer of these powers.

For example, Machipango, my adopted “brother-in-law,” consistently prepares the most virulent snuff I have tried. Harsh and potent, it has left me puking with as little as one or two puffs. He and his sons consume heroic doses of the stuff, and they take silent pride in their daunting reputation among the tobacco elite.

Some snuff makers produce more fragrant blends, which may be more or less caustic, more or less sharp and intoxicating when consumed. One time, the octogenarian Ahuanari shared an unusually fragrant and mild blend with me. It gave me none of the usual nicotine high but imprinted a nauseating, sickly-sweet smell into my nose, the olfactory equivalent of maraschino cherries (I hate maraschino cherries) and left me feeling queasy for hours. I never went back for more.

Rascally old Oyeyoyeyo, may his shaman’s soul soar for eternity, made the best snuff of all: consistently fragrant, strong, bitingly clean, and strongly euphoric, like some divine rare chili pepper from the Mexican highlands. He lived a long and vigorous life but recently faded into the immortal shamans’ infinite starry night. How I miss Oyeyoyeyo, and my pilgrimages to his house to barter for seri …

Join us for our next conference!

Tradition attributes these variations in potency, character, and especially painfulness to the spiritual strength of the man who prepared the snuff. I am convinced this is well founded, yet I also suspect that subtle variations in raw materials and preparation style may be physical proxies for these spiritual imponderables.

Tobacco is considered an almost exclusively male domain. Men prepare the snuff from fresh, green tobacco leaves plucked from the living plants. I have seen and collected two varieties, one with white flowers, the other with red. Both belong to the cultivated botanical species Nicotiana tabacum. I’ve heard mention of a yellow-flowered variety nearby, which I suspect may be the wild Nicotiana rustica.

I soon came to savor the sharp sting of tobacco, crave the euphoric rush of nicotine, even appreciate the purifying bouts of retching that sometimes follow a binge…

The Matsigenka make no large-scale tobacco plantations; if they did, worms and other pests would quickly devour the crops. In fact, they have trouble keeping the pests away from even their modest gardens, which consist of a few clumps scattered around the sandy clearing by a house. Between the bountiful pests and the prolific consumption of snuff by its human keepers, tobacco is in high demand and short supply most of the time.

Once picked, the green leaves are dried over a smoldering fire on a rack made of tree fibers loosely woven on a circular frame that is reminiscent — incongruous in the Amazon lowlands — of a snowshoe. The crisp leaves are then crumbled by hand into a small black ceramic pot used especially for this purpose, and then ground patiently into a fine green powder with a wooden pestle. The preparer sifts the powder through a clean cloth and finally mixes it with the ash obtained from burning the bark of an exceedingly rare tree species known simply as seritaki, tobacco bark.

My biologist colleague Douglas Yu collected a botanical voucher and eventually we identified it as belonging to an obscure family of trees, Lepidobotriaceae, distantly related to the sour-tasting herb known as wood sorrel (oxalis). Our collection was the first specimen of this botanical group ever found in Peru, as the family was previously known only from Africa and Central America. Why the Matigenka use this uncommon tree, among the thousands of species available in their lush rainforest environment, is a mystery to me; perhaps oxalic acid (also present in wood sorrel) is involved?

When bark from this tree is unavailable, a number of substitutes can be used to prepare tobacco snuff, including almond-scented Sloanea and fragrant Bignoniaceae lianas, though they are considered inferior.

The sifted tree ash is stored in a pompori shell of its own. A man preparing tobacco snuff thumps the gray-white ash into the clay pot holding the freshly ground tobacco powder. He adds the ash gradually, mixing and grinding with a pestle and constantly checking the color of the mixture on saliva-wetted fingertips. Too much tobacco powder — too “blue” in Matsigenka parlance (their language, paradoxically in such a lush and leafy climate, has no unique word for “green”) — makes for dusty and ineffectual snuff; too much ash (too “white”) burns like lye.

When he is satisfied with the consistency and color — typically a rich powdery celadon — he scrapes the snuff out of the clay pot with a second pompori. The circular scraping of the shell’s rim on the gritty black clay produces a distinctive, hollow resonance that makes a seri enthusiast’s mouth (and nose) water. He tests the batch immediately on an eager victim: fresh tobacco snuff is the strongest and most painful of all.

And so it was that I came to commit, and pay heavily for, an egregious though not irreparable faux pas during my own infantile grappling on the lowest rungs of the shamanic ladder. It happened with none other than Abanti, an enigmatic man from a distant settlement who later revealed himself to be the most important shaman-healer of the Manú River.

After that memorable if overindulgent initiation with Shumarapage, my maturing taste for pungency had led me to barter for tobacco with many men, on many occasions. And yet when I asked Abanti to sell me tobacco, he hesitated.

Yes, I had encountered some unwilling sellers before; they either had no plans to prepare tobacco anytime soon, or else had so little that they were loath to sell it. In these cases, they simply responded, “My tobacco is done! I’ve snuffed all the plants up,” or “My pompori is almost empty.” But this was different. Abanti seemed to be sizing me up as if he wasn’t sure I was worthy.

Finally he said, “My tobacco is very expensive.”

“How expensive?” I asked.

“I’ll think about it,” he said, “and tell you later.”

It seemed clear that Abanti was reluctant to sell me tobacco for some reason. I didn’t know him very well at that time, and he had always been somewhat reluctant to speak with me about medicinal plants or other healing practices, always deferring to some elder, presumably more knowledgeable person. So I didn’t press him about it and figured I’d find someone else to trade with. But a few days later, Abanti appeared in front of the cavernous palm-thatched longhouse that had once been a school and was now my temporary campsite.

He was there because Padre Pascual, a Catholic priest living in a mission town some five days downstream by motorized canoe, had just arrived in a boat laden with soggy cardboard boxes and burlap sacks full of clothes, salt, machetes, and fishing line. Abanti and dozens of other people from widely scattered hamlets had come to examine the Padre’s wares and spectate at the sermon planned for later that afternoon. The Padre spoke no Matsigenka and most of the villagers understood little if any Spanish, but the sacks of trade goods were a good catalyst for theological communication.

“I made tobacco for you,” Abanti said.

“Really?” I was surprised.

“Yes. You must try it.”

“Right now?” I turned to look some ten yards away, towards the concrete steps of the new tin-roofed lumber schoolhouse, where the Padre stood surrounded by ragged villagers who gawked as his stockpiles were carried up from the port.

The Padre was a recent arrival from Spain, a real hard-liner, and I had already been warned about his suspicions regarding my anthropological work. Unlike his predecessor, who had lived in the region for decades and whom I knew well, had even befriended — Padre Pascual was openly critical of Americans, scientists, and bilingual literacy enthusiasts (those who thought the indigenous language should be taught first at school, then Spanish). I was all three. He looked in my direction with a scowl.

“I can stop by your house after Mass,” I suggested to Abanti.

“Now,” he said.

“Let’s go inside.” I ducked into the cool shadow of my borrowed longhouse. Though I had little hope or even desire of overcoming the Padre’s negative views of my research, I still didn’t think it would be wise to subject him, of all people, to the spectacle of puffing and hacking and green snot that was to follow. I could already hear the rumors about a crazy gringo sniffing drugs to get high. I sat down towards the back, checking to make sure the Padre couldn’t see us over (or through) the half-wall of palm slats that circled the building.

And so, not fifteen yards from an exceptionally xenophobic, righteous, and avowed enemy of paganism, Abanti dipped a curassow bone into a giant white shell, inserted it into my nose, and began blowing narcotic green tobacco snuff deep into my sinuses.

I forgot all about the Padre: It was the best tobacco I had ever tried.

I had never before understood the Matsigenka metaphor of the shaman ingesting tobacco like a hummingbird sucking flowers, given how pungent and painful it usually was. But now it made perfect sense: Abanti’s snuff was sweet and lush and rapturous, like some divine nectar. I couldn’t get enough of it, and lost count of how many doses he gave me.

I stopped out of prudence, not necessity, remembering the Padre’s imminent Mass. Breathless and lightheaded, not really thinking about what I was saying, I blurted out, “Pocha!” — which means “sweet.”

Abanti frowned and looked at me in disbelief.

“‘Sweet’?”

“Yes, your tobacco is delicious! Really fragrant. Very sweet, like the hummingbird sipping nectar!”

Abanti ignored the shamanic metaphor and asked, “You are saying my tobacco isn’t katsi?”

At this point I realized I was in serious trouble and began backpedaling furiously. “What I mean is, it’s not that your tobacco is actually ‘sweet’ to the taste, it’s just that it’s very strong but also very good. It’s intoxicating, but it doesn’t burn my nose. I don’t get tired of it, so I can snuff more and get truly intoxicated. It’s very good!”

Abanti gathered together the tobacco kit and stood up to leave.

“Your tobacco?” I asked pathetically, still hoping to close the deal. We hadn’t even negotiated a price.

“I’ll give it to you Thursday. At Shantanta’s.” His younger brother, Shantanta, had invited me and several others to drink ayahuasca later that week. Abanti was apparently going too.

I don’t remember what else I said to him as I sat there in giddy consternation. He left me alone and joined the others who had crowded around the Padre’s sacks and boxes. I could have kicked myself: the gaffe was so obvious in hindsight. I should have known better than to insult his tobacco as “sweet” when what was valued was precisely its painfulness. At least he wasn’t offended enough to back out of the tobacco deal. No one else seemed to have any to sell, but Thursday would come soon enough.

Little did I know what awaited me.

The next few days were a flurry of Mass, collective baptisms, community meetings, and frenzied bartering between the Padre and community members, “the price of each soul,” as an eighteenth-century Franciscan missionary once noted, “being an ax of Biscaya.” There was little point in continuing my own research with the community’s attention thus distracted, so I passed the time cleaning and organizing my campsite.

Then the Padre left and the village returned to its usual pace. On Thursday, as scheduled, Abanti’s youngest brother came over in the late afternoon and invited me to drink ayahuasca with him that night.

“I have warmed up the vine-brew,” he said, using one of the precautionary euphemisms for ayahuasca that the Matsigenka employ to show respect for the sacred vine on the day of the ceremony, avoiding its common name. Ayahuasca can cause intense bouts of vomiting and diarrhea, purging a man of physical and spiritual impurities.

The Matsigenka take ayahuasca only during the rainy season, which lasts from about November through May. This is also the main hunting season for most game animals, especially woolly and spider monkeys, which have stringy, lean meat during the dry season but fatten up on the abundant forest fruits that ripen with the rains. Indeed, Matsigenka men take ayahuasca specifically to improve their hunting skills, literally “to have good aim” (nokovintsatira). I have often heard men state as a matter of fact, “I drink ayahuasca, I go out the next day hunting, and I bring home two spider monkeys.”

At the same time, ayahuasca puts men in direct touch with spirit beings known as saangariite (“the invisible, pure ones”), who control access to supernatural powers as well as natural resources. In this way, the Matsigenka are like many other tribes, including our own; associations between shamanism and hunting appear to be nearly as old as the human species, as evidenced in ancient rock art throughout the world.

Avoiding ayahuasca during the dry season is about more than hunting, however. The dry season is the season of agriculture, when men carve small gardens from the forest and burn the fallen trees to produce ash fertilizer — the swidden gardening mentioned earlier. The saangariite spirits, too, plant their own gardens, and thus in the dry season, the spirit world, like the human world, is full of smoke and blazing fires that can disorient or even kill a shaman’s roaming soul. The first rains put out those fires and clear the shaman’s path for safe travels into the cosmos.

I arrived for the earthly ceremony at the nearby cluster of houses soon after dark, provisioned with a sleeping bag, a tape recorder (this was participant observation, after all), a beautifully decorated cushma (cotton tunic) to wear during the ceremony, and a fresh roll of toilet paper: still the one civilized trapping I had never quite weaned myself off, and that my Matsigenka friends also appreciated. Six or seven men from the same hamlet had already donned their cushmas and gathered, sitting on cane mats strewn around the sandy plaza. Some chatted quietly, some took preparatory rounds of tobacco snuff, others relaxed in silence. The last glow of daylight faded and dark clouds loomed, leaving a vague, hazy patchwork of stars. It looked like rain. Abanti still wasn’t there.

Shantanta kept asking me what time it was. “This ‘sun’ you gave me is broken.” He held up the battered, strapless remains of an unfortunate Casio slung around his neck like a talisman, an ongoing relic from a tobacco exchange a few years prior. I got the hint: My price for participating in the ceremony would be a new digital wristwatch, or if I really went for the hard bargain, a repair job on the old one.

Matsigenka men always expect trade goods in exchange for tobacco and for the privilege of participating in an ayahuasca ceremony, even between each other; the going price (for gringos at least) is a Casio wristwatch.

As a rookie ethnographer I had been initially dismayed at the Matsigenka fascination with digital technology. But with time I came to see their almost fetishistic desire for waterproof wristwatches as a mirror image of my own fascination with their shamanistic substances and paraphernalia. The symmetry of this relationship between juxtaposed technologies is reinforced by price structure: Matsigenka men always expect trade goods in exchange for tobacco and for the privilege of participating in an ayahuasca ceremony, even between each other; the going price (for gringos at least) is a Casio wristwatch.

It was well past eight o’clock and Abanti still hadn’t arrived. His house was almost an hour’s walk away, on forest paths that would be as dark as an underground tunnel on an overcast night like this. Finally Shantanta gave up waiting. He ordered his two wives and numerous sisters and nieces throughout the hamlet to douse water on all the hearths. Any form of artificial illumination — a flashlight, a candle, a match, the faintest spark from a smoldering ember, even the glow of a digital watch’s backlight — can be mortally hazardous during the ayahuasca session, burning the shaman’s soaring soul.

The ceremony was about to start.

“Where is your brother?” I asked. “He’s not coming?”

“He’ll be here later,” said Shantanta, “but we must start now or we will still be drinking at dawn.” The Matsigenka always consume ayahuasca fresh and usually finish a batch on the evening of the same day it was prepared. Depending on the quantity of brew and the number of guests, the session can end before midnight or continue until nearly dawn. Only if day breaks will any remnants of the brew be stored for another occasion — but this rarely happens. Shantanta was expecting this to be a long night.

As is customary, the men gathered around him on their mats as he indicated where each person was to sit, forming a loose semicircle. We all faced east, obeying one among several tacit ceremonial rules: No excessive talking, especially in the early part of the ritual, no farting (but deep, vigorous belching to relieve nausea is permitted — indeed, developed to a high art); anyone about to vomit should call for the large cooking pot, reserved especially for this purpose, so as not to spill the purged impurities onto the ground (the collective sum of vomitus is buried the next morning); and most important, still no artificial illumination until the leader of the session declares it over.

Shantanta opened the ceremony, calling each person by name in a simple but unvarying ritual formula.

“Nee,” he says (literally, “Look,” i.e., “Here it is”), each time as he passes a tiny gourd with a small amount of liquid to a guest, one by one, in sequence around the circle.

The guest asks in reply, “Iro pishavogaa?” (“This is what you warmed up?”) and then gulps down the intensely bitter contents in a few sips. He returns the gourd and receives several refills, finally declaring, “Intaga” (“Enough”).

Discover the Indigenous Reciprocity Initiative of the Americas

The session leader serves each guest in this fashion around the circle, and finally himself. He puts the gourd back in the cooking pot, covers it with a banana leaf, and waits. After an interval of ten or fifteen minutes he repeats the ceremony, always following the same order among the guests, over and over throughout the night until the entire batch is finished. To be the guest who finishes the brew is a special honor for that session. Depending on the number of guests and the size of the batch, each participant can consume up to a half pint of the powerfully psychoactive beverage over the course of an evening. The result is a gradual crescendo of hallucinogenic trance that peaks at a higher level with each successive round and gradually dissipates about four hours after the last cup is served.

This night, the visions began for me with unusual speed and clarity. I was floating along a lush and artfully lit path through the forest, observing the beauty of each individual herb, vine, tree, and fruit. An uncanny invisible presence was transmitting esoteric information to me about the healing and spiritual properties of each plant. I heard a voice singing a simple but sublime melody of words in a cryptic language that sounded vaguely Mayan. I tried to follow the chanting with my own voice. It seemed that great mysteries were about to be revealed, hidden powers conveyed.

I was floating along a lush and artfully lit path through the forest, observing the beauty of each individual herb, vine, tree, and fruit.

But as the session continued and I drank dose after dose, each more bitter than the last, the initial scintillation of mystery and euphoria was washed away by a rising tide of nausea that invaded my entire body. I shifted position, from sitting, to curled on my side, to lying on my back, to stretching out yoga-style, hoping to find some arrangement that would bring relief. My palms were clammy, I shuddered at the brew’s bitter trace down my throat, my bladder was nagging, but I dared not stand. The implacable physical discomfort grew into a total, existential revulsion. Black clouds obliterated the feeble starlight and I was surrounded by a deep and menacing darkness. The companions who presumably lay close by now seemed unimaginably remote, but their occasional rustlings or whispers reminded me of their incongruous proximity, which only confused and nauseated me more. The clear, colorful visions of the opening moments of the session were gone, and I had entered a plane of Euclidean perplexity, twisted cognition, and gnawing dread.

After a long while, I heard dogs barking. A distant hail, awkward footsteps approaching, the shuffling of bodies on mats. Someone said in a hushed tone, “It’s him.”

Abanti had arrived.

He greeted several of his kinsmen by name and probed his way among the prostrate, intoxicated bodies in the pitch black, finally taking his place in the center of the group alongside his younger brother, Shantanta. He explained that he had heard a pair of tinamou (partridge-like forest birds) calling near his house at sunset and began to describe the scene in vivid, evocative detail, rich with onomatopoeia and specific hunting vocabulary. He had set out with his arrows, calling to the birds and listening for their response, and crept softly in their direction through the dark forest. He saw one silhouetted in roost against the faint glow of the sky, shot an arrow, but missed. The two birds flapped away on nervous wings, calling again from a distant tree. He recovered his spent arrow and followed them again to where he thought they should be, but they cried out from another direction altogether. He tried calling again but the birds were wary and elusive. He eventually gave up on the hunt, realizing it was past time to leave for his brother’s house for the ceremony. But his flashlight batteries were weak, and halfway there they had faded out altogether. He described the path bend by bend, how he had stumbled over fallen logs and crawled in the dark through rough stretches where brush had blocked the path. He dared not say the word in the midst of an ongoing ceremony, but it was clear he had been worried about snakes.

Every nuance in his voice and detail of his story was magnified by the deep ayahuasca trance, and Abanti’s tale took on mythic proportions: an eternal parable of the wayward hunter who has lost his skills, been abandoned by his guardian spirits, and gone astray in the wild. He continued his narrative before a rapt audience, describing his sufferings in the dark forest until the moment he heard dogs barking in the distance, realized he was close to Shantanta’s house, and finally emerged from the shadows.

The initial scintillation of mystery and euphoria was washed away by a rising tide of nausea that invaded my entire body…

The conclusion, though unspoken, was manifest: He had come to drink ayahuasca to renew his mystical contact with the capricious spirits of the forest and reclaim his prestige as a hunter and as a shaman.

When he finished his tale, I dissolved into the enveloping blackness.

Some time later I heard Shantanta utter the standard invitation to drink, “Nee! Here it is.” His voice hovered, as if coming from various places at the same time, and I thought it was directed at me.

I sat up and reached through the shadows in the direction of his voice, saying, “Where is the gourd?”

“Not you!” said Shantanta as soft laughter rippled through the group. “This is for Abanti.”

I heard Abanti gulping down the liquid and then spitting with an eerie whistling sound, dispelling either the bitter taste or some looming supernatural presence. I lost myself in byzantine meditations and lay down again.

After another long silence, I heard Shantanta beseeching close by me, “Nee!”

Once again I sat up and groped in the dark for the gourd. Someone chuckled.

“You again!” admonished Shantanta. “This isn’t yours, it’s for Abanti!”

Abanti began swallowing and I lay down and was gone. After what seemed like another infinite interval but may have been only a matter of seconds, I heard Shantanta’s voice close beside me, again offering the gourd. This one, I was sure, was mine. And so for a third time I sat up, extended my hand, and asked for the gourd.

My shadowy companions laughed again, louder this time, and someone jeered, “What does he think he’s doing?”

Shantanta echoed in consternation, “What are you doing? Not you! This is for Abanti!”

I felt ashamed, as if pierced by a thousand disapproving glances, and fell into a chaos of swirling greens, reds and browns. I lost all notion of time.

Eons later, penetrating this void like a lifeline, came Abanti’s voice, calling to me.

I sat up, groggy, and tried to find my bearings. The sky was black, with a blacker horizon. “What is it?”

Another bright cloud of green pain expanded inside of me and turned in on itself, swirling into iridescent fractals that enveloped us both.

“I brought the tobacco,” he said. “Come here.”

I crawled, feeling my way among clumsy bodies towards his voice. “Here?” I asked, as I reached out and felt the hem of a cotton tunic.

“No,” a shadow answered, and a disembodied hand guided me to one side. “Abanti is over here.”

At last I scooted up and sat cross-legged in front of Abanti’s dim form as he rustled through his net bag. I heard more than saw him unplug the snail shell and begin serving up a dose of snuff, the scratching of bone tube against porcelain shell wall muted by the copious powdery contents.

“Who’s first?” I asked.

“You,” he said. “Nee.”

“Where is it?” I probed in the darkness for the bone tube.

“Here.”

I found the tube, felt the striations indicating the receiving end, held my breath, and inserted the tip of the tobacco bone in my nose.

Abanti blew the tobacco with fast furious puffs. The snuff entered my nostrils as a sequence of chartreuse explosions that expanded inwards and upwards like a chain reaction. It felt as if my brain had been illuminated from the inside. I gasped at the wildfire that roared through my sinuses and seared the nerves deep in my face. It was more than pain, it was suffering. He was punishing me, there was no doubt, but the pain he inflicted, though intentional, was not cruel or gratuitous. It was an initiation, a rite of passage: He was teaching me a lesson.

As he rang the bone against the shell, it occurred to me that he was summoning someone, or something…

The first dose was done and Abanti was already scraping up another. There was no question of refusal. As he rang the bone against the shell, it occurred to me that he was summoning someone, or something.

The jets of powdery tobacco entered me once again. Another bright cloud of green pain expanded inside of me and turned in on itself, swirling into iridescent fractals that enveloped us both. There was no way to look at it, since it was everywhere: a million unblinking eyes, a peacock’s fanning tail, a rainbow of undulating woven patterns, the shimmering plumage of a hummingbird.

I realized for the first time that Abanti, despite his modesty and circumspection, was in fact a powerful shaman. The deference the other men had shown him that evening was already a clue, but he had finally revealed his mastery to me. What he was transmitting to me through that bone tube was no longer a physical substance, it was knowledge, a living power — a sacrament. Some part of Abanti was entering me.

Or not Abanti exactly, but rather a silent twin, a shamanic doppelgänger that had been transmitted to him by some other master. It was both part of him and yet also more than he was. It was ancient and eternal but needed a human host. It could confer practical insights and mystical powers, but it was also capricious and probably had its own agenda.

What he was transmitting to me through that bone tube was no longer a physical substance, it was knowledge, a living power — a sacrament. Some part of Abanti was entering me.

This invasive alien force was melding with my spirit through a portal opened up by ayahuasca and consummated by tobacco. It felt as if Abanti had taken me to some secret and dreadful and holy place: a cave, a sacrificial altar. The sensation was both euphoric and frightening.

I don’t know how many doses he gave me. At some point I whimpered, “Intaga,” and Abanti stopped. Tears streamed down my face. My breath came in sobs. My hands trembled, my face went slack and numb. Thick, dark mucus began to flow out of swollen sinuses onto my lips, neck and chest.

An uncanny buzzing sound surrounded me, sometimes near, sometimes far, sometimes in front or behind, on one side or the other. I could never locate it, much less identify its source. A hummingbird seemed to be playing hide-and-seek with me. There was something unbearable about that sound, not so much menacing as utterly incomprehensible and disorienting. I was confused, with no sense of spatial or temporal reference. The euphoria drained out of me once again and in its place came nausea, rising like a sickening tide that lurched to the pulse of that dizzying hum. There are times when one can hold firm and fight off the nausea of tobacco or ayahuasca intoxication through force of will. This was not one of those times.

A hummingbird seemed to be playing hide-and-seek with me. There was something menacing about that sound …

“Jiromanka,” I called out: The pot.

Somewhere from the darkness appeared a large aluminum pot, the designated vomitorium for the session. No sooner had I set my hands on the handles than I began heaving and retching with singular violence. I was not just losing my lunch, as they say: it was as if my very soul were prying itself loose from within the depths of my bowels. Long-forgotten sins and transgressions poured forth like bile, physical manifestations of a spiritual purge. I vomited and vomited and vomited some more. There was nothing left to vomit and yet I still heaved and retched and groaned in agony. I wanted to give the pot back to someone, to put the sour-smelling shadows far away, and yet I feared more would come out. And it did. So I clung to the pot’s twin handles as if to a life preserver in a stormy sea. My heaves finally came up dry, but my abdomen continued contracting in revulsion against the toxins that still coursed through my body.

Finally I was spent. I coughed the last remnants from my mouth. My hands shook as I wiped filth, snot, and tears from my face onto the sleeve of my cushma;the thought of searching for toilet paper was unbearable. I handed the pot back into the darkness.

According to custom, I told each member of the group, in the same order as the brew had been served, “Nokamarankake”: “I vomited.” As if they hadn’t noticed. And each one said back, politely, “Ario?”: “Is that so?”

What seemed like hours passed. Then I heard Abanti’s voice beckoning.

“Nee,” he said. I reached out in the darkness and he handed me the complete tobacco kit: fully loaded snail shell, cloth stopper, and L-shaped bone.

“Katsi pisere?” asked Abanti, without irony: “Is your tobacco painful?”

He was calling it mine now. I had earned it.

“Katsi,” I whispered.

* * *

Later that evening, the final cup of ayahuasca brew fell to me, giving me the tacit honor of closing the session. The occurrence is supposed to be providential — ayahuasca herself chooses — but I suspect Shantanta meted the dosages toward the end to nudge this privilege towards me.

“Pitsoa!” he exclaimed, as if surprised: “You finished.”

“Notsoa,” I said: “I finished.”

And I repeated the phrase, according to custom, to each person in sequence, ending with Abanti.

“Jaroka pikanti,” he replied: “You don’t say?”

We have been friends ever since.

Art by Trey Brasher.

———–

*This article was originally published in Broad Street Magazine

Take a minute to browse our stock:

Did you enjoy reading this article?

Please support Chacruna's work by donating to us. We are an independent organization and we offer free education and advocacy for psychedelic plant medicines. We are a team of dedicated volunteers!

Can you help Chacruna advance cultural understanding around these substances?