- Therapists, Trainers, and Researchers from Lykos’ Phase 3 MDMA-Assisted Therapy Studies Respond to Concerns in ICER’s Draft Evidence Report - May 7, 2024

- Towards an Ethos of Equity and Inclusion in the Psychedelic Movement - December 18, 2019

- Blinded by the White: Addressing Power and Privilege in Psychedelic Medicine - March 13, 2019

- Towards an Ethos of Equity and Inclusion in the Psychedelic Movement - December 18, 2019

- Blinded by the White: Addressing Power and Privilege in Psychedelic Medicine - March 13, 2019

The lack of racial diversity is a strong indication that the burgeoning field of psychedelic medicine is recapitulating the same systemic problems around accessibility and diversity that have long plagued the fields of medicine and mental health

As the field of psychedelic medicine gains momentum, the glaring underrepresentation of people of color in the movement is hard to miss. Psychedelic researchers, conference presenters, therapists, doctors, study participants, and patients are all largely White. The lack of racial diversity is a strong indication that the burgeoning field of psychedelic medicine is recapitulating the same systemic problems around accessibility and diversity that have long plagued the fields of medicine and mental health. As White researchers and clinicians, we are intending to speak to other White people about an issue that many don’t think or talk much about. Unlike people of color, White people are not forced to contend with these issues; yet, the topic of racism is one that directly involves all of us, one that we participate in on a day-to-day basis, and have the responsibility to address in a direct and personal way.

We recognize that there is no perfection, and that our contribution to this discussion may illuminate areas where we are blinded by our whiteness. We take full responsibility for any misrepresentations or blind spots and welcome feedback regarding anything that strikes the reader as offensive or misguided.

Although this article focuses on the lack of representation of people of color in psychedelic medicine, we also recognize that, for the field to reach its true liberatory potential and move away from the heavy dominance by straight able-bodied cis White men, we must take up an intersectional perspective, considering issues of accessibility for all minority identities and levels of class privilege. Some of the issues described below, such as the Drug War, are particular to people of color. Other issues, such as the potential obstacle of engaging in psychedelic work with a therapist who doesn’t understand your identity, or the distress that stems from discrimination, are also concerns for LGTBQI, gender creative, and other people from target groups. Furthermore, the lack of representation of women in positions of power, and the failure to recognize their contributions to the field, is a telling marker of the male dominance that still pervades the movement.

In our experience as therapists and researchers in the field, we’ve found that the perception among many of our White colleagues is that the question of racial diversity is important, but incredibly complex and challenging. In spaces that are dominated by whiteness, many of us have a tendency to drop the topic quickly, rather than finding motivation to directly address its complexities. Turning a blind eye is tantamount to supporting the inequitable systems that maintain the profound discrepancy in who receives appropriate and necessary health care. There are a handful of people, mostly people of color, who are talking and writing about these issues and making valuable suggestions about how to address the discrepancy and increase accessibility. Throughout this article, we will highlight some of their vital contributions. We will also shed light on some of the limitations, blind spots, and pitfalls that we perceive within ourselves and among fellow White colleagues in the field.

In this article, we will challenge the narrative that the issue of diversity is too complex to prioritize at this early stage of the movement, and encourage psychedelic practitioners to engage the realities of racism and White supremacy with more rigor and sensitivity. Our use of the term White supremacy is not limited to the hate groups that openly proclaim the superiority of whiteness, but is primarily a reference to the “overarching political, economic, and social system of domination” that benefits White people at the expense of people of color.1 First, we will offer some background that describes how the current disparity came to be, and then we will suggest some ways to address it. We will emphasize the importance of educating ourselves about the systems of White domination that pervade US history and the factors that uphold the insidious racism of today.

The Numbers

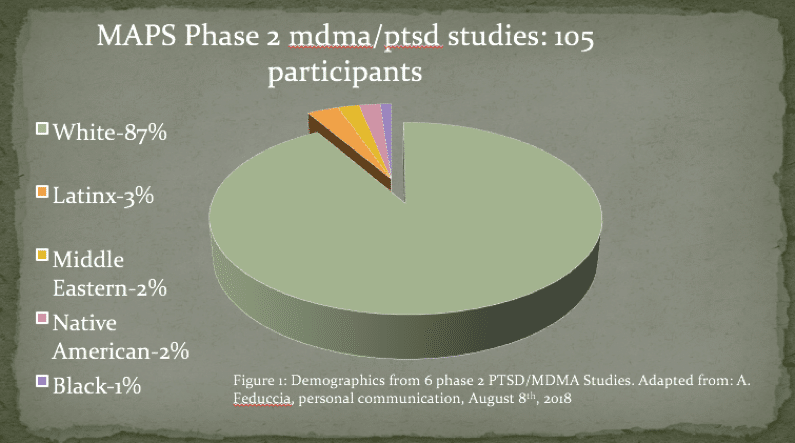

Monnica Williams, a researcher in the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies’ (MAPS) MDMA for PTSD trials and prolific writer on the topics of race and diversity, has brought attention to this issue through a number of articles and talks through which she is actively advocating to increase awareness and inclusivity in the field. She, along with Michaels, Purdon, and Collins,2 conducted a recent meta-analysis of 18 studies of psychedelic-assisted therapy between 1993 and 2017, finding that 82.3% of participants were non-Hispanic White. We found similar results in an informal survey we completed of ketamine-assisted psychotherapy in the Bay Area (Herzberg, 2018). All of the eight practitioners who responded to the survey were white. They had treated a total of 100 patients, 89% of whom were White. Corroborating these numbers are the Phase 2 data for MAPS’s MDMA for PTSD research, depicted in the chart below (A. Feduccia, personal communication, August 6, 2018).

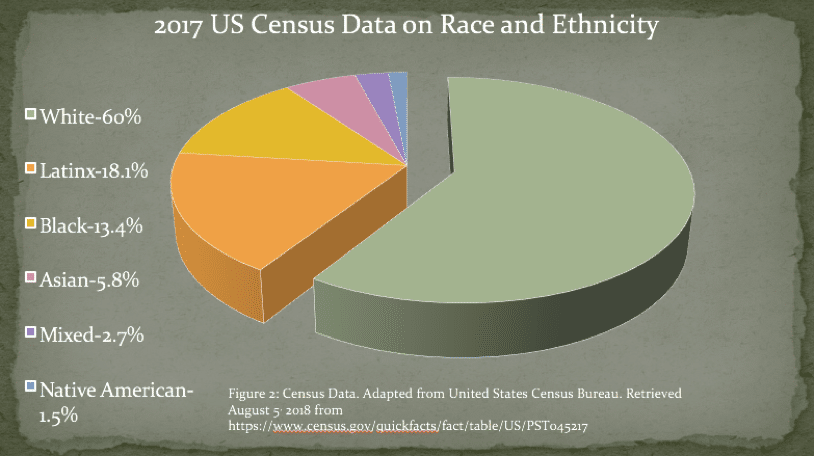

Compare this to the United States demographics, in Which whites make up only 60% of the population, while non-white races and ethnicities make up a full 40%.3 Blacks and Latinx make up a particularly small percentage of participation in the psychedelic field. In the MAPS Phase 2 research, only 1% and 3% of participants were Black and Latinx, respectively, compared to the 13.4% of general population that is Black and 18% that is Latinx.

How Did We Get Here?

White supremacy is deeply entrenched in the fields of medicine and research, as well as the government’s century-old drug policy, and is a key factor in the exclusion of people of color from the psychedelic medicine movement. There are myriad examples of scientific research and medicine being used as tools to oppress select minority groups, in particular, African Americans, Latinx, and Native Americans. We will mention just a few of the most well known, as they are essential information for anyone working in the field (See Harriet Washington’s book4 “Medical Apartheid” for a more detailed account).

First, race is a constructed notion, developed in the fifteenth century by Portuguese slave traders to justify the enslavement of African people under the guise that those of African descent were inferior to Europeans. Since the dawn of the scientific era, attempts have been made to use science to validate the constructed notion of race and to justify structures of White supremacy. The centuries-old practice of “scientific racism” attempts to use the study of genetics and other forms of scientific research to demonstrate the inferiority of certain racial and ethnic groups and to justify and perpetuate racial and ethnic discrimination. Many prominent historical figures have subscribed to and promoted these ideas, including Thomas Jefferson, who called for science to demonstrate the “obvious inferiority” of African Americans.

The eugenics movement is another set of beliefs and practices broadly enacted by White men throughout the world over centuries; practices which led to atrocious examples of violence and oppression. In short, the eugenics movement attempts to “improve” the quality of the human population by weeding out “undesirable” people and groups. Thousands of women of color and poor, incarcerated, and disabled women have been sterilized through coercion, manipulation, or force. There are reports of Black women going to the doctor for an unrelated procedure being sterilized without consent. In Madrigal v. Quilligan, ten Latina women filed a class action lawsuit against LA County hospital obstetricians, who reportedly coerced them into sterilization while in labor and without informed consent. This problem continues to occur in the US today.

In the well-known 1932 study, commonly referred to as the “TuskegeeExperiment,” but more aptly called “the United States Public Health Service study of untreated syphilis in Black men,”622 poor African-American sharecroppers were enrolled in a study to observe the natural progression of syphilis over 40 years. They were told they were being treated for “bad blood,” and that the study would last for 6 months. Instead, it lasted for four decades. The men were never told of their diagnosis, nor were they offered treatment. This took place in the 1940s, after penicillin had been proven to be effective in curing the disease. Many of the men died of syphilis, and 40 of their wives and 19 of their children contracted the disease.

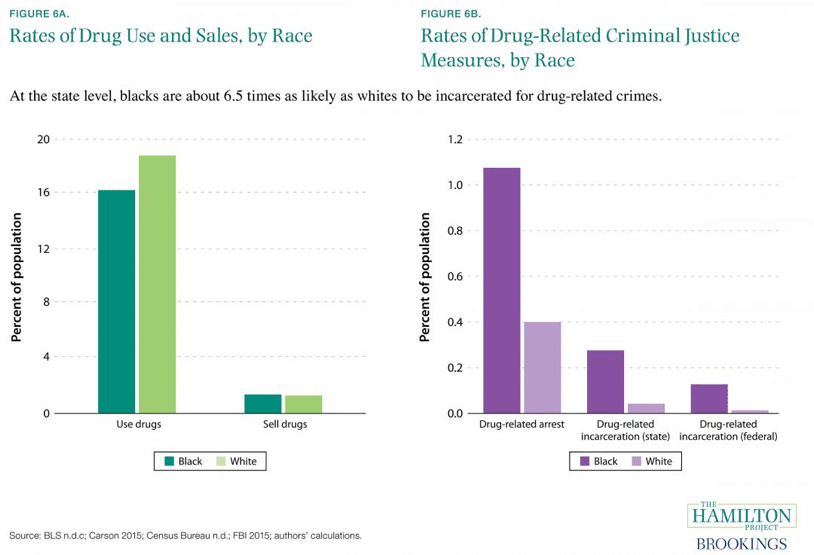

Over the past century, the nation’s War on Drugs has specifically targeted substances used by immigrants and minority populations as a method of oppression and control.(*) The repercussions of these policies are illustrated in the charts pictured here.

African Americans use less drugs than Whites, and sell them at about the same rate, but are 6.5 times as likely to be incarcerated for a drug-related crime.5 Meanwhile, nearly 80% of people in federal prison, and almost 60% of people in state prison for drug offenses, are Black or Latinx.6 A felony remains on one’s record permanently, leading to disenfranchisement, difficulty accessing housing, jobs, and social services, and, ultimately, high rates of recidivism. As Nicholas Powers explains in his talk at the 2017 Horizons conference, the Drug War has made a major impression on attitudes towards drugs in communities of color, leaving many understandably hesitant to associate themselves with these substances.

The 1980s phenomenon of the “crack baby” is a good example of the Drug War’s racial targeting and slandering. The term “crack baby” has since been discredited. It has been shown that in utero exposure to cocaine may have some minor effects on cognitive and circulatory functioning, but nothing like what was being broadcasted by the media at the time, which aggressively promoted a constructed racial narrative of the criminal, degenerate, crack-addicted black woman putting her child at great risk and placing a huge burden on society as a whole. This media campaign served to demonize and condemn Black culture, leading to excessively harsh sentencing for crack-related charges and the mass incarceration of people of color.

Where are We Now?

Racism and White supremacy are not things of the past. They live on, not just in small pockets of the South, but in all of our structures and institutions, and in the everyday practices of White people. They show up in psychedelic medicine as pervasively as they do in other fields and settings. For example, Sara Reed just published a powerful critique of White Feminism and her experience of being silenced by racism disguised as progressive thinking at a psychedelic conference.7 Reed’s personal account calls to attention the propensity for any White person to recapitulate racist dynamics, even in the most well-intended efforts to deconstruct racism. In order to effectively address the problems stemming from racism and white supremacy, it is essential to look carefully at both structural and individual dimensions.

Institutional Racism

On a structural level, many individuals of color experience the research and medical fields as entities that don’t take care of them and do not consider their lives as important. As a result of some of the history described above, in addition to countless instances of daily discrimination, these institutions are often associated with abuse, violence, and oppression, rather than health, wellbeing, and the development of scientific knowledge. Such impressions are not just reflective of past issues, but are evidenced throughout our health care system today. In her poignant article recently published in Chacruna, Monnica Williams lays out the variety of ways in which African Americans receive inferior care, and the devastating consequences that result, including a higher risk of death in childbirth for black mothers and their children.8

Solid Ground, a Seattle-based non-profit working to end poverty and racism, defines institutional racism as “the systematic distribution of resources, power and opportunity in our society to the benefit of people who are White and the exclusion of people of color.” A 2016 study indicates that the average Black worker earns about 75% percent of the hourly wage of the average White worker.9 This system-wide income disparity places significant limitations on the ability to afford health care. The high cost of psychedelic therapy is generally cost-prohibitive for lower-income individuals, and there are few examples of organizations implementing programs to increase accessibility. Psychedelic therapy training programs also tend to be quite costly, excluding individuals with fewer resources who are, more often, people of color, and ultimately contributing to the ongoing underrepresentation of therapists of color in the field. For example, the two most prominent psychedelic therapy training programs, MAPS and CIIS, charge $9500 and $10,000 for their respective programs. A similar disregard for lower-income needs is evident in many research protocols. Participation in a psychedelic research study is time-intensive and may require taking time off of work; however, there is generally no compensation for participation in the research.

The massive underrepresentation of people of color among participants, researchers, therapists, and, most dramatically, among those who hold leadership positions, is a prime example of institutional racism. As Michaels 10 demonstrate in their research, this discrepancy has been evident over the past 25 years throughout psychedelic research across the globe. In response to this disparity, MAPS has made some recent attempts to recruit more therapists and participants of color. They have also formed an advisory council to address issues of diversity. However, a comprehensive effort to shift the blatant disparity has yet to occur.

Another, more subtle example of institutional racism can be found in the screening tools and diagnostic categories used in psychedelic research, which generally do not acknowledge that trauma and other types of mental illness may show up in different ways for people of different racial and ethnic groups.11

Individual Racism

White practitioners often do not have a good enough understanding of the history and current state of white supremacy, their own whiteness and participation in practices of racism, the lived experience of minority populations, or the traumatic impact of racism and implicit bias on people of color.

In psychedelic medicine and research, individual racism shows up as an inherent power dynamic that takes shape when the practitioner is White and the patient or participant is a person of color. Both the practitioner and patient enter the work with a personal (though perhaps unconscious) relationship to racism, power, and privilege. These dynamics are inevitably expressed in the treatment and, if not addressed explicitly, can be enacted in harmful ways. White practitioners often do not have a good enough understanding of the history and current state of white supremacy, their own whiteness and participation in practices of racism, the lived experience of minority populations, or the traumatic impact of racism and implicit bias on people of color.

The practitioner’s ignorance to the reality of racism, what Robin DiAnglo (2012) has called “racial illiteracy,” compromises safety in the therapeutic relationship, inhibiting the patient’s ability to give voice to racial distress and to talk about the racial dynamics that are present in the therapeutic relationship. For example, while discussing this issue with an African-American colleague, she noted, “with a White therapist I might wonder, ‘does she really get it?’ I’d feel like our worlds were so different … It’s hard to trust that they’re open to talking about it, or that they’re not judging you when you bring it up – like you’re ‘pulling the race card’ or something.”

Where Do We Go from Here?

The following set of considerations are not exhaustive, but are offered here in hopes of furthering the conversation around concrete steps decision-makers, clinicians, and researchers can take in order to ameliorate the unjust practices and structures outlined above.

Come join us in Queering Psychedelics! Buy tickets here

Culturally-Sensitive Education

First, it is important that we acknowledge the roots of psychedelic medicine in indigenous cultures around the world, and the indigenous wisdom that informs current models of practice. In a talk he gave at the Breaking Convention conference in 2017, Darren Springer suggests that greater acknowledgment of the indigenous roots of psychedelic medicine could serve as a means to help people of color feel more personally connected to the work. Further, organizations involved in psychedelic medicine must address the problem of cultural appropriation so as to not perpetuate patterns of White colonialism. In highlighting the destructive impact of colonialism on indigenous healing practices, Ifetayo Harvey12 asks the question, “What would happen if these outsiders used their resources to repair the harm that has been done to indigenous communities?” Harvey’s question calls forth the need to make reparation and redistribution of resources a standard practice among business ventures providing psychedelic medicine.

Psychedelic practitioners must have a much more broad and integrated awareness of the legacy of White supremacy and racist politics and practices in the field, so as to support their ability to recognize and respond to the understandable hesitation and mistrust that may arise in the treatment.

Furthermore, it is of vital importance to centralize the discourse surrounding racism and its many manifestations in psychedelic medicine. Education around diversity should be an essential part of training in the psychedelic field, woven throughout a training program, rather than relegated to the margins; considered just as important as the education required for assessment and treatment. Psychedelic practitioners must have a much more broad and integrated awareness of the legacy of White supremacy and racist politics and practices in the field, so as to support their ability to recognize and respond to the understandable hesitation and mistrust that may arise in the treatment.

Practitioners must be adept at sensitively broaching issues of difference in the therapeutic relationship. We might remember here our African-American colleague’s poignant question about working with a White therapist, “Does she really get it?” Given the asymmetrical nature of the relationship, the practitioner should not rely on the patient to bring up their feelings or thoughts about racism or to provide education about the experiences and challenges of their demographic group. Monnica Williams13 recommends that practitioners ask directly about patients’ experiences of racism, carefully creating a safe space to discuss these issues, while ensuring that they themselves are informed about the range of potential race-related experiences that a person of color might encounter. White practitioners can educate themselves through reading works and listening to talks authored by people of color, participating in experiential trainings focused on dismantling racism and White supremacy, and engaging in critical discourse with White peers.

Living in a deeply racist culture, even the most well-intentioned and anti-racist White Americans cannot avoid internalizing racist perceptions and participating in practices of racism.

Lastly, and perhaps most importantly, White practitioners must engage in inner work around their participation in maintaining the current structures of oppression. Living in a deeply racist culture, even the most well-intentioned and anti-racist White Americans cannot avoid internalizing racist perceptions and participating in practices of racism. As Camille Barton14 adeptly points out, racism is often unconscious and linked with feelings of shame and guilt. It can be challenging to recognize racism in ourselves, often triggering defensiveness when we are forced to confront our racist behaviors and practices. It is therefore necessary that we conduct a deep and thorough inventory of our whiteness, looking carefully at practices that perpetuate racism, engaging the help of anti-racist educators and activists to bring awareness to our blind spots, and remaining open and receptive to feedback.

Listening and Adaptation

Efforts towards a more inclusive practice must include a diversity of perspectives. This can be achieved by supporting the efforts led by people of color already in motion, and creating opportunities for people of color to get involved. Dialogue can be facilitated by the formation ofworking groups that aim to bring together people from diverse backgrounds to brainstorm creatively, investigate how to make the work more accessible, and put ideas into practice.15 The formation of advisory boards with voting and veto power is an effective way to include leaders and individuals from minority communities who can offer their perspectives and guidance in an ongoing way. In addition, Patricia James, medicine woman, cross-cultural expert, and Cheyenne pipe carrier and priest, has suggested that a council of elders steeped in the tradition and practices of medicine work could be of great benefit to the field, particularly as psychedelic medicine becomes increasingly influenced by medicalized models (personal communication, 2018). This council could offer important guidance in thinking about how to maintain an ethical and respectful relationship to medicine work grounded in integrity, love for our fellow human beings, and respect for our planet.

Representation

Representation of one’s identity is an important way to signal to the individual that they belong and that the issues that affect them most intimately will be understood and addressed.

Recent empirical evidence indicates that practices of inequality continue to have a significant impact on the hiring process: “a member of a privileged group is almost always presumed to be the ‘safer bet’”.16 This implicit bias towards those with privilege contributes to the overrepresentation of those who already hold power. Efforts towards increasing representation are also limited by the high cost of psychedelic therapy training programs and inadequate scholarship opportunities for people of color. In research and clinical practice, representation of one’s identity is an important way to signal to the individual that they belong and that the issues that affect them most intimately will be understood and addressed.

Hence, organizations should hold representation of people of color as a primary aim in recruitment and hiring. In addition, conferences and public events should ensure that minority groups are represented among the organizers and presenters. Conference organizers need to ensure that discussions around race are well-facilitated by moderators who can directly address controversial or offensive comments from audience members or panelists. Training programs for psychedelic therapists must provide affordable opportunities for individuals from minority communities. Lastly, those involved in recruitment for psychedelic research should engage in culturally-sensitive outreach practices by building personal relationships with, and showing up as allies for, people of color17 and partnering with organizations and agencies that are serving minority communities.18

Accessibility

We believe that making psychedelic medicine more accessible to people of color can support the long-standing need for reparations for the genocide, enslavement, and practices of oppression that have ravaged communities of color for centuries. Psychedelic therapies can be made more accessible through instituting practices of community-supported medicine. Psychedelic clinics can institute privilege-based sliding scale fee systems that take into account not only income and financial resources, but also family resources, parents’ level of education, access to health care, loans, experiences of having lived in poverty, etc. This model of sliding scale slides not just down, but also up, so that those who have privilege and resources subsidize those who have not had the same kind of opportunities for success. Institutions can offer grants and donations directed towards funding underrepresented groups, compensation for participation in research, and scholarships to conferences and trainings reserved for people of color. Businesses involved in psychedelic medicine can reinvest profits to support underserved communities, prioritizing open praxis, and supporting the general good over profit.

Efforts can be made to create protected spaces for people of color to safely experience these medicines without having to censor themselves or deal with the many challenges, vulnerabilities, and power dynamics inherent in working with White therapists, researchers, and facilitators. Nicholas Powers makes this point in his talk at the 2017 Horizons conference, explaining that, while white people have had these kinds of spaces for decades, allowing myriad opportunities for safe exploration, many people of color have not had that opportunity. Ideally, there would be enough practitioners of color that patients and participants could be paired with someone who reflects their identity.

Means and Ends

Whereas some may argue that the highest priority in psychedelic medicine is FDA approval and the means by which we get there are secondary, we believe that the ongoing exclusion of people of color from psychedelic treatments, even in this nascent stage, reinforces the dangerous notion that practices of inequity are acceptable so long as the ends seem to justify the means. As Dr. King19 so eloquently noted, “In the final analysis, means and ends must cohere because the end is preexistent in the means, and, ultimately, destructive means cannot bring about constructive ends” (p. 67). In the fight for civil and cognitive liberties, exclusion of any group negatively impacts the entire endeavor. Nobody is free while others are oppressed.

Note:

This paper was presented at Cultural and Political Perspectives in

Psychedelic Science, a symposium promoted

by Chacruna and the East-West Psychology Program at the California Institute

of Integral Studies (CIIS), San Francisco, August 18 and 19, 2018.

(*)John Ehrlichman, Nixon’s Drug Policy Advisor, admits directly that his Drug War policies were not intended to support public health, but instead, to control minority and counter-culture groups through a targeted, slandering media campaign.

Opening image credit: Black Lives Matter Demonstration. Photo credit by Vincentchapters pbs.org (source).

References

- DiAngelo, R. (2012). What does it mean to be white: Developing white racial literacy. New York City, NY: Peter Lang. ↩

- Michaels, T., Purdon, J., Collins, A., & Williams, M. (2018). Inclusion of people of color in psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy: A review of the literature. BMC Psychiatry, 18(245), 1–9. Retrieved from: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-018-1824-6 ↩

- United States Census Bureau. (2017). Population by race and Hispanic origin: 2012 and 2060. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/mso/www/training/pdf/race-ethnicity-onepager.pdf. ↩

- Washington, H. A., (2008). Medical apartheid: The dark history of medical experimentation on black Americans from Colonial times to the present. New York City, NY: Anchor. ↩

- The Hamilton Project. (2016, October 21). Rates of drug use and sales, by race; rates of drug related criminal justice measures, by race. Retrieved from http://www.hamiltonproject.org/charts/rates_of_drug_use_and_sales_by_race_rates_of_drug_related_criminal_justice ↩

- Race and the Drug War. (2018). Drug Policy Alliance.Retrieved from http://www.drugpolicy.org/issues/race-and-drug-war ↩

- Reed, S. (2019). The damage of White Feminism. Chacruna. Retrieved from: https://chacruna.net/the-damage-of-white-feminism-an-anecdote/ ↩

- Williams, M. (2019). How White Feminists oppress black women: When feminism functions as White Supremacy. Chacruna. Retrieved from: https://chacruna.net/how-white-feminists-oppress-black-women-when-feminism-functions-as-white-supremacy/ ↩

- Daly, M. C., Hobijn, B., & Pedtke, J. H. (2017, September 5). Disappointing facts about the black-white wage gap. Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco Economic Letter. San Francisco, CA: Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco ↩

- Michaels, T., Purdon, J., Collins, A., & Williams, M. (2018). Inclusion of people of color in psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy: A review of the literature. BMC Psychiatry, 18(245), 1–9. Retrieved from: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-018-1824-6 ↩

- Michaels, T., Purdon, J., Collins, A., & Williams, M. (2018). Inclusion of people of color in psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy: A review of the literature. BMC Psychiatry, 18(245), 1–9. Retrieved from: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-018-1824-6 ↩

- Harvey, I. (2016). Why the psychedelic community is so white. Retrieved from: https://www.psymposia.com/author/ifetayo-harvey/ ↩

- Williams, M. (2016). Race-based trauma: The challenge and promise of MDMA-assisted psychotherapy. MAPS Bulletin, 26(1), 32–37. ↩

- Barton, C. (2017). The elephant in the room: The need to address race in psychedelic research. MAPS Bulletin, 27, 1–3. Retrieved from https://maps.org/news/bulletin/articles/427-bulletin-winter-2017/6964-the-elephant-in-the-room-the-need-to-address-race-in-psychedelic-research ↩

- Springer, D. (2017) Racial-delic. Paper presented at Breaking Convention, June 30 – July 2, University of Greenwich, London, UK. ↩

- Perry, I. (2011). More beautiful and more terrible: The embrace and transcendence of racial inequality in the United States. New York City, NY: New York University Press. ↩

- Michaels, T., Purdon, J., Collins, A., & Williams, M. (2018). Inclusion of people of color in psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy: A review of the literature. BMC Psychiatry, 18(245), 1–9. Retrieved from: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-018-1824-6 ↩

- Powers, N. (2018). Black masks, rainbow bodies: Race and psychedelics. MAPS Bulletin, 28(1), 47–51. Retrieved from https://maps.org/news/bulletin/articles/429-maps-bulletin-spring-2018-vol-28-no-1/7268-black-masks,-rainbow-bodies-psychedelics-and-race ↩

- King, M. L. (2011). The trumpet of conscience. Boston, MA: Beacon Press. ↩

Take a minute to browse our stock:

Did you enjoy reading this article?

Please support Chacruna's work by donating to us. We are an independent organization and we offer free education and advocacy for psychedelic plant medicines. We are a team of dedicated volunteers!

Can you help Chacruna advance cultural understanding around these substances?