- Introduction to Women and Psychedelics - July 26, 2024

- Eight Frequently Asked Questions About Ayahuasca Globalization - February 13, 2024

- Ten Tips for Standing in Solidarity with Indigenous People and Plant Medicines - January 18, 2024

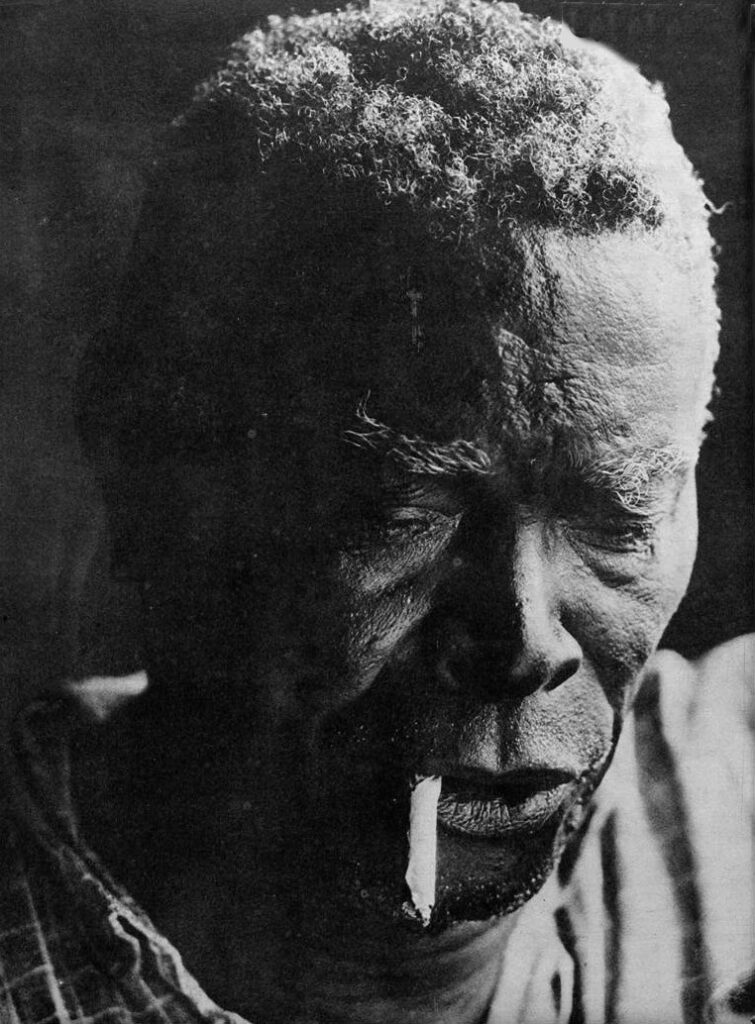

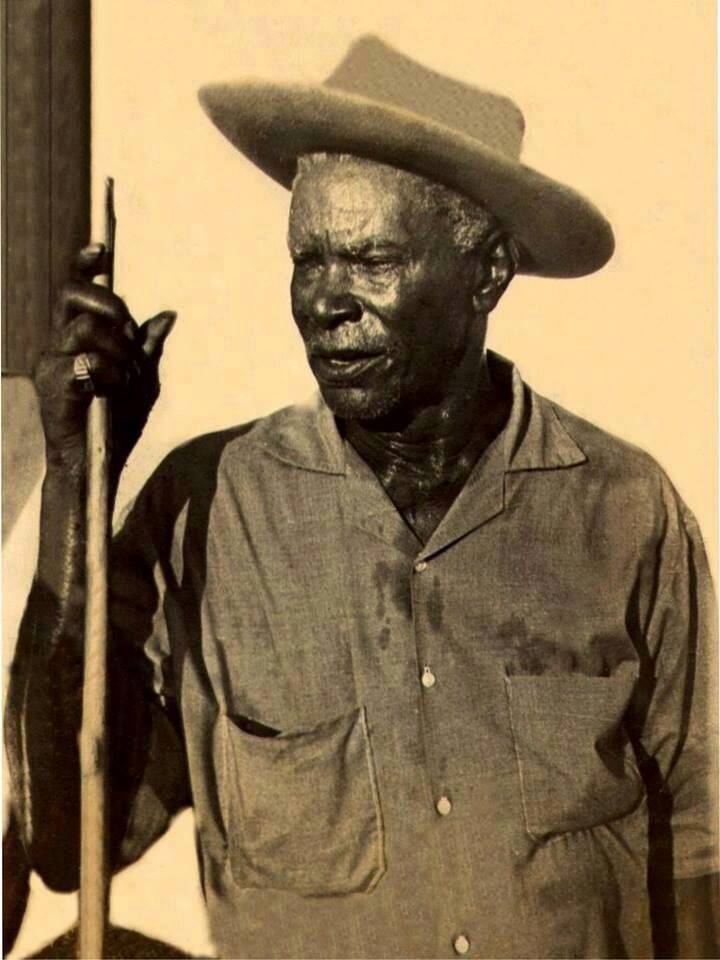

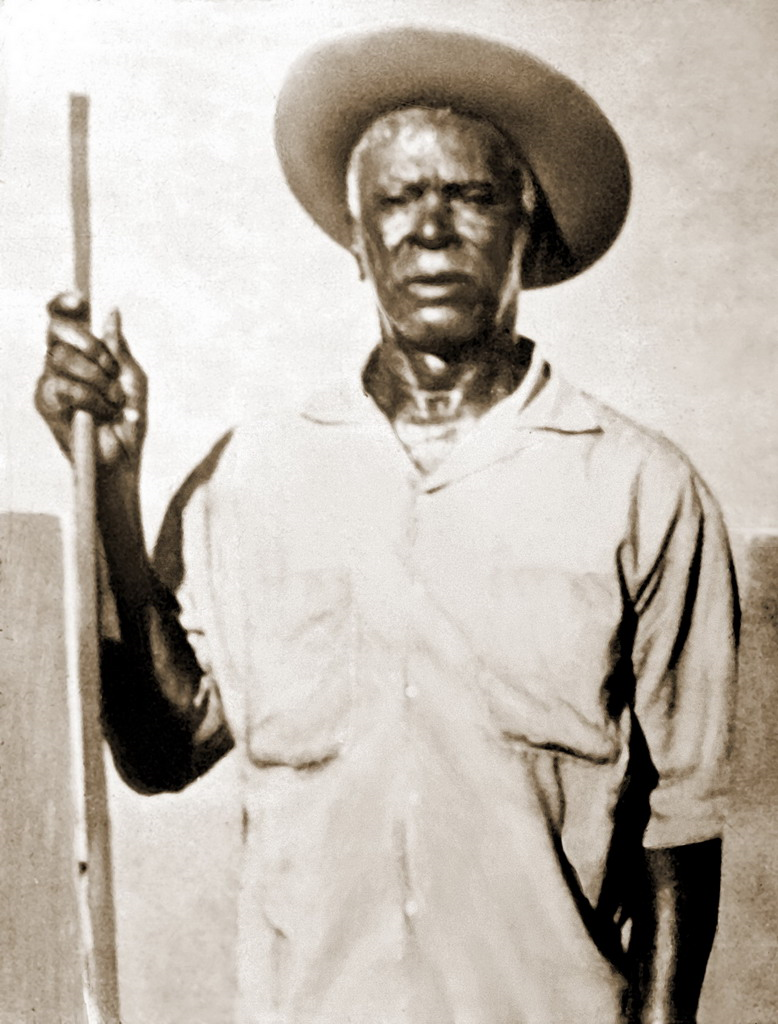

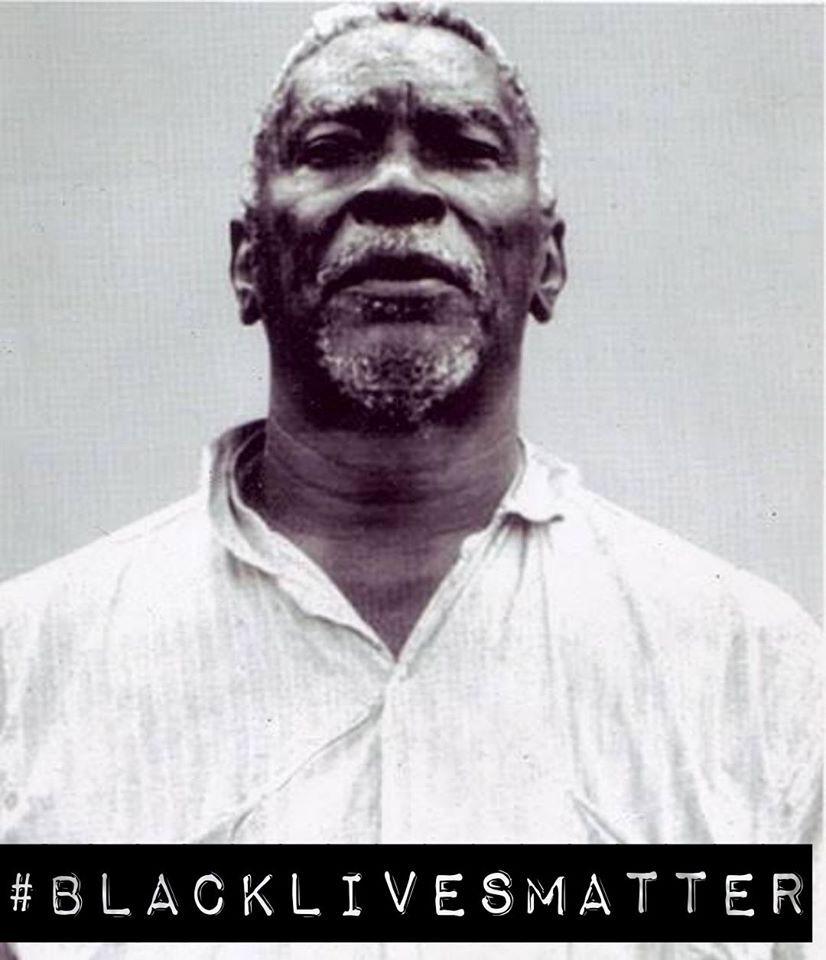

You probably know about ayahuasca. You probably love the Amazon. You probably support Black Lives Matter (at least, I hope so!). What you probably don’t know is that a Black man who lived in the Amazon played a major role in the history of ayahuasca. In this short essay, I will introduce you to Raimundo Irineu Serra, who founded Santo Daime, the oldest Ayahuasca religion in Brazil.

A Slave’s Grandson Goes to the Amazon

Raimundo Irineu Serra was born in 1890 in a small town in Maranhão, Brazil’s poorest state, just two years after the country abolished slavery

Raimundo Irineu Serra was born in 1890 in a small town in Maranhão, Brazil’s poorest state, just two years after the country abolished slavery (Moreira & MacRae, 2011). The grandson of enslaved Black people, he grew up in poverty and never had the opportunity to attend school. Coming from a background filled with adversity and inequality, none of his childhood friends could have imagined that Irineu Serra would overcome such difficulties and structural racism, but he did. Nonetheless, he suffered many challenges and struggles along the way; struggles that are connected to the ones Black people in America and worldwide endure today.

Seeking a better life, Irineu left Maranhão in Northeast Brazil and made the long journey to the Amazon, to the territory now known as Acre. He arrived there in 1912, motivated by the government’s promises that rubber tappers could earn a prosperous living in the forest. That promise was a lie, of course. The rubber economy was built upon the merciless exploitation of workers who usually lived in extremely poor conditions. To make matters worse, due to the biopiracy of rubber seedlings, Brazil lost its monopoly on rubber production to the plantation system of British colonies in Malaysia, which caused a socioeconomic collapse in the region (Moreira & MacRae, 2011).

Thus, thousands of immigrants who, like Irineu Serra, dreamed of having a better life in the Amazon, were utterly abandoned. It was in this context that Irineu, almost without hope, sought ayahuasca.

From Moon Woman to Black Man: Initiation with Ayahuasca

According to reports by his followers, Mestre Irineu was probably initiated into the mysteries of ayahuasca in Peru by indigenous shamans (Moreira & MacRae, 2011). When he took the enigmatic potion, Irineu began to have spiritual revelations that transformed his life and his understanding of the brew. According to Daimista mythology, on a clear and beautiful night, Irineu took ayahuasca and, as he looked up at the moon, he saw a beautiful and wondrous lady. She asked him, “Who do you think I am?” Amazed, Irineu looked at her and replied: “My lady, you must be a Universal Goddess!” (Moreira & MacRae, 2011). This female entity was later identified as the “Queen of the Forest,” and is also understood to be a manifestation of the Virgin of the Immaculate Conception.

She then directed her disciple to go through a series of fasts and trials, after which she granted him the right to make a wish. Young Raimundo asked to become a great healer to help people, and requested that she put all her healing powers into that brew. She granted him this wish, and thus Irineu Serra became Mestre Irineu.

Santo Daime: A Cultural Mosaic

Through this encounter between a female deity, a Black man, and an ancestral magical beverage, ayahuasca was renamed “Daime.”

Through this encounter between a female deity, a Black man, and an ancestral magical beverage, ayahuasca was renamed “Daime.” Daimistas say the word comes from a formal and somewhat archaic imperative form of the verb dar, “to give”: Dai-me força, dai-me amor, “Give me strength, give me love,” they chant in their ceremonies. In order to navigate the pathways of the mysterious dimensions of ayahuasca, one must a adopt a humble position before its power, and ask: “Give me!”

Mestre Irineu began to blend the ritual consumption of ayahuasca with elements from other spiritual traditions, including folk Catholicism, indigenous spirituality, European esoterism, and Afro-Brazilian religions, giving rise in the 1930s to an original philosophy known today as Santo Daime. Thus, since its inception, Santo Daime has been characterized by syncretism and exchange with other spiritual practices, constituting itself as a cultural mosaic. This allowed the group to adapt to the complex and discordant context of the time and to be molded by different conceptions of the world.

This account, which reveals Mestre Irineu as a shaman who built bridges between different worlds, gives us clues for understanding the presence of Christian elements in Santo Daime. However, some people, especially middle-class White populations of the Northern Hemisphere, are resistant to these Christian associations. It is commonly said that Mestre Irineu “Christianized” ayahuasca. What is left unsaid is that he also “Africanized” Christianity, giving it new meanings for poor people of the rubber plantation: a Christianity that rescued the self-esteem of racially mixed rubber tappers; a decolonial Christianity. We need only to look at Santo Daime’s origin story: The Catholic Virgin of the Immaculate Conception reveals her spiritual mission to Irineu Serra, but she is also simultaneously the Queen of the Forest and the “Universal Goddess.” Just as ayahuasca is a symbiotic mixture of two plants that produce a unique brew, Mestre Irineu’s philosophy is an anthropophagic mixture of different cultures that produces an authentic identity.

A Musical Experience

Like many other Daimistas, I like to call Santo Daime a “musical doctrine.” After he established this initial contact with the Queen of the Forest, she told Irineu that she wanted to be praised through cheerful songs. Irineu replied that he did not know how to sing; at which, she ordered him to open his mouth so that she could teach him. At that moment, Irineu was inspired to sing “Lua Branca,” the first hymn of Santo Daime. Since that time, the sacred texts of the religion are the musical hymns “received” by Daimistas from all over the world. Mestre Irineu’s hymnbook, known as O Cruzeiro (“The Holy Cross”), includes 132 hymns that form the basis of the group’s religious practice. Organized chronologically, these songs are considered by Daimistas as divine, spiritually inspired messages.

It is virtually impossible to understand Santo Daime without considering its musical elements. Music is not merely an aspect of Santo Daime practice; rather, it creates the enchanted universe of “The Doctrine.” The soundscapes of the ceremonies are capable of carrying away and bringing back people from their visionary journeys, and are a potent illustration of the symbiosis between psychedelics, culture, spirituality, and the body (Labate et al., 2016). In Santo Daime ceremonies, music is so important that people not only listen to hymns, but also sing and dance to them for as long as 12 hours, depending on the ceremony: The Daimista is a dancer by nature! Santo Daime ceremonies, referred to as trabalhos (“works”), are, most essentially, musical experiences.

From Jail to Jerusalem

As a Black man who dared to cultivate an anti-hegemonic spirituality, Mestre Irineu suffered persecution and was strongly stigmatized for a long time. In his early days in the Amazon, he was the target of police actions against “witchcraft.” He was even shot by the police.

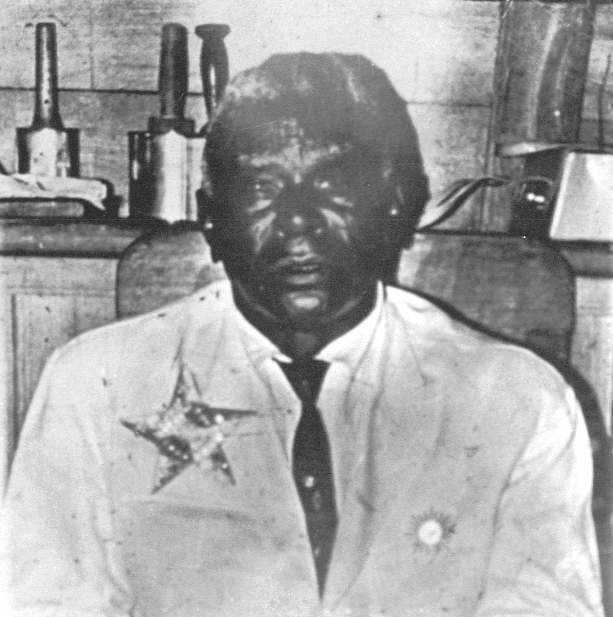

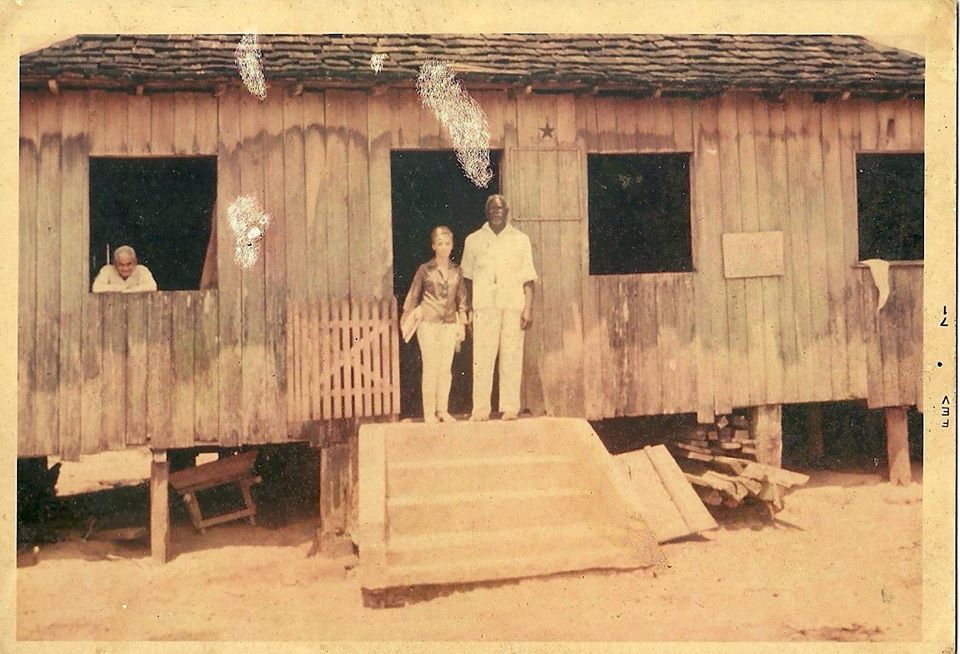

As a Black man who dared to cultivate an anti-hegemonic spirituality, Mestre Irineu suffered persecution and was strongly stigmatized for a long time. In his early days in the Amazon, he was the target of police actions against “witchcraft.” He was even shot by the police. For these reasons, he moved from the Amazon interior to the state capital, Rio Branco. But that didn’t make things better. Irineu Serra, who also caught everyone’s attention due to his height—he was about 7 feet tall—was accused of charlatanism and quackery in Rio Branco, and even went to prison in 1942, after a siege of his home by 40 police officers (Moreira & MacRae, 2011). This incident motivated the Master to move once again, this time for good. And yet, his persecution led Irineu to develop diplomatic skills, allowing him to move between different social circles. He established alliances with important politicians while rescuing people who lived in virtual slavery at the rubber camps. Mestre Irineu’s cosmopolitical diplomacy also included plants, animals, and nature. He was able to consolidate his religious group, which grew to a few hundred people, making Irineu a regionally respected citizen.

Today, the movement founded by Irineu Serra is present in at least 43 countries on all inhabited continents. From Tokyo to Berlin, from New York to Jerusalem, Santo Daime is one of the most widely spread Brazilian religious movements.

This consolidation allowed Santo Daime, decades later, to catapult into a national and international diaspora, undertaken especially by two of his followers, Padrinho Sebastião Mota de Melo and his son, Padrinho Alfredo Gregório de Melo. Today, the movement founded by Irineu Serra is present in at least 43 countries on all inhabited continents. From Tokyo to Berlin, from New York to Jerusalem, Santo Daime is one of the most widely spread Brazilian religious movements. It has also played an important role in the regulation and legalization of ayahuasca worldwide (Labate & Assis, 2016).

This is not to say that things have become easy for Daimistas. On the contrary, persecution continues; now, globally. In the past three decades, Daimistas have been arrested, and dozens of liters of the Daime brew have been seized worldwide. But Irineu Serra’s followers are resilient: they get it from him!

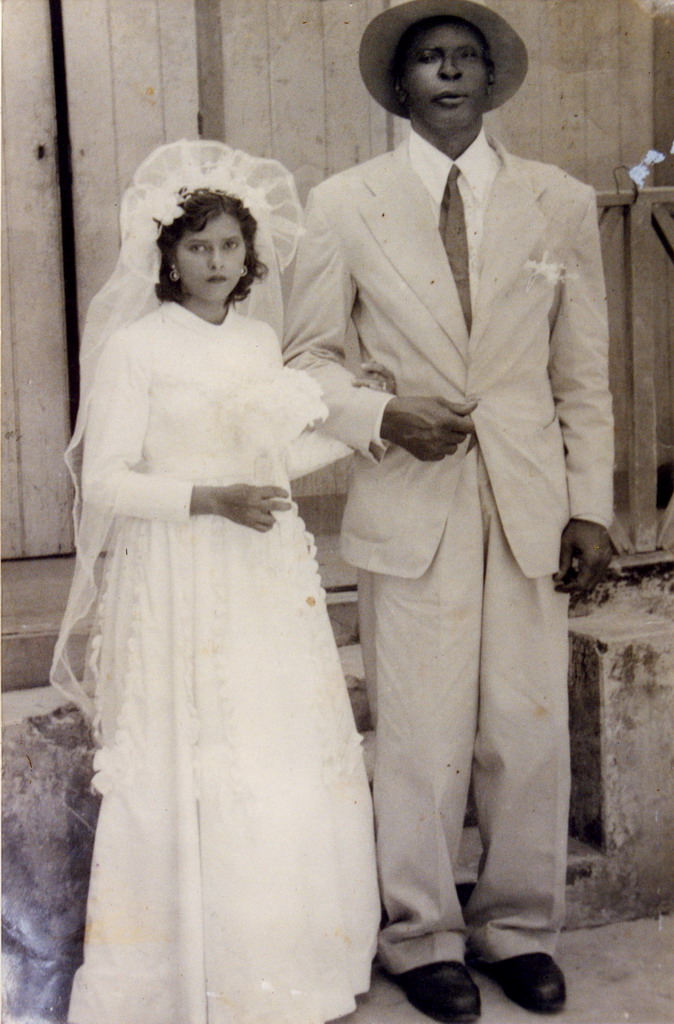

The Anthropomorphization of Ayahuasca: Irineu Becomes Juramidam

Mestre Raimundo Irineu Serra died on July 6, 1971. His followers believe that his death symbolizes the fulfillment of his mission on Earth; by then, his doctrine was ready. He then came to be recognized by Daimistas as “Juramidam,” his spiritual name: “Imperial Master Juramidam.” Ayahuasca, understood by Daimistas as a “divine being, transformed into liquid” (Silva, n.d.) has become synonymous with Mestre Irineu himself. The brew has transformed into a person, and Irineu Serra has become a plant: Daime and Irineu merge into one. As he once said: “I am Daime and Daime is me.”

Today, the tomb of Mestre Irineu is a place of international pilgrimage and an important tourist destination in the city of Rio Branco. The ayahuasca formula developed by Irineu was consecrated not only in Santo Daime, but in several other religious groups as a safe method of preparation and a very special ayahuasca brew. The original community continues to function in the same place, led by Irineu Serra’s widow, Madrinha Peregrina Gomes Serra, who is now 83 years old and continues to participate actively in religious life.

Roots

Ayahuasca practices appear to be going through a “Whitening” process, and its founding figures are being erased from history. Revitalizing the memory of historical figures such as Mestre Irineu from the Global South, the cradle of ayahuasca, is an important way to counteract this process.

Today, ayahuasca is becoming mainstream. And yet, alongside this valorization of traditional knowledge, this movement has also commercialized the ayahuasca brew and in many cases disenchanted its practices. Ayahuasca practices appear to be going through a “Whitening” process, and its founding figures are being erased from history. Revitalizing the memory of historical figures such as Mestre Irineu from the Global South, the cradle of ayahuasca, is an important way to counteract this process.

Mestre Irineu is a fascinating personage in the history of ayahuasca. His life teaches us that discussions around this “drink that has incredible power” (Serra, n.d.) are not only about psychedelics, but also about diversity, environment, culture, and overcoming prejudice and social stigma. The trajectory of Raimundo Irineu Serra reminds us, once again, to acknowledge the presence and contributions of Black people everywhere, including wherever ayahuasca is found and consumed. May this simple testimony contribute to keeping the memory of this great Black Brazilian man alive. As he tells us:

“Here I come to my end

I leave my narration

To always remember

The old Juramidam.”

(Serra, n.d.)

Art by Clancy Cavnar.

References

Labate, B. C. & Assis, G. (2016). The religion of the forest: Reflections on the international expansion of a Brazilian ayahuasca religion. In B. C. Labate, C. Cavnar, & A. Gearin (Eds.), The world ayahuasca diaspora: Reinventions and controversies (pp. 57–76). New York: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315551425

Labate, B. C., Assis, G. & Cavnar, C. (2016). A religious battle: Musical dimensions of the Santo Daime diaspora. In B. C. Labate, C. Cavnar, & A. Gearin (Eds.), The World Ayahuasca Diaspora: Reinventions and controversies (pp.99-121). New York: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315551425

Moreira, P. & MacRae, E. (2011). Eu venho de longe: Mestre Irineu e seus companheiros [I come from afar: Mestre Irineu and his companions]. Salvador: Edufba. https://doi.org/10.7476/9788523211905

Serra, I. (n.d.). Estou aqui[I am here]. O Cruzeiro. Retrieved from https://www.nossairmandade.com/hymn/301/EstouAqui

Serra, I. (n.d.). (n.d). Eu tomo esta bebida [I drink this drink]. O Cruzeiro. Retrieved from https://www.nossairmandade.com/hymn/92/EuTomoEstaBebida

Silva, O. R. (n.d.). Ser Divino. Daime sorrindo. Retrieved from https://nossairmandade.com/hymn.php?hid=1540

Take a minute to browse our stock:

Did you enjoy reading this article?

Please support Chacruna's work by donating to us. We are an independent organization and we offer free education and advocacy for psychedelic plant medicines. We are a team of dedicated volunteers!

Can you help Chacruna advance cultural understanding around these substances?